TIN VĂN TRÊN

ART2ALL

Album

Empire of Dreams ;

White Labyrinth ( Charles Simic / Nguyễn Quốc

Trụ )

School for Dark Thoughts ( Charles Simic / Nguyễn Quốc

Trụ )

Tốt nghiệp TH,

vô ĐH

Richie @ Wonderland with Friends 14.6.2018

Số báo mới nhất về Zweig. Đọc loáng thoáng

ở tiệm sách, thấy OK quá. GCC chẳng đã từng đọc

Võ Phiến song song với Zweig. Cả số báo này, cũng

đọc trong tinh thần đó, thế mới

thú, nhưng cũng nhìn ra sự khác biệt giữa hai nhà

văn, về cùng 1 xứ sở đã mất. Với Zweig, là Âu

Châu, với VP qua GCC, là 1 xứ Mít, cũng đã mất!

Empire of Dreams ;

White Labyrinth ( Charles Simic / Nguyễn Quốc

Trụ )

School for Dark Thoughts ( Charles Simic / Nguyễn

Quốc Trụ )

Mở ra Poet's Choice, là Borges

I.

NIGHTINGALES

spring's messenger, the lovely-voiced nightingale

-SAPPHO

I WISH I’D BEEN on the street in Madrid on that night in 1934

when Pablo Neruda, who was then Chile’s consul to Spain, told Miguel

Hernandez that he had never heard a nightingale. It is too cold for nightingales

to survive in Chile. Hernandez grew up in a goat-herding family in the

Province of Alicante, and he immediately scampered up a high tree and imitated

a nightingale’s liquid song. Then he climbed up another tree and created

the sound of a second nightingale answering. He could have been joyously

illustrating Boris Pasternak's notion of poetry as "two nightingales dueling."

I once told this story to the Writer William

Maxwell, and he said that learning how to sing like nightingales in

treetops ought to be a requirement for poets. It should be taught, like

prosody, in writing programs. The Romantic poets might have agreed,

Wordsworth called the nightingale a creature of “fiery heart”; Keats

inscribed its music forever in his famous ode ("Thou wast not born fur

death, immortal bird!"); John Clare observed one assiduously as a boy

("she is a plain bird something like the hedge sparrow in shape and the

female Firetail or Redstart in color but more slender then the former and

of a redder brown or scorched color then the latter"); and Shelley declared:

A Poet is a nightingale, who sits in darkness

and sing, to cheer its own solitude with sweet sounds; his auditors are

as men entranced by the melody of an unseen musician, who feel that they

are moved and softened, yet know not whence or

why.

The singing of a nightingale becomes a metaphor for writing poetry

here, and listening to that bird-that natural music-becomes a metaphor

for reading it.

One could write a good book about nightingales

in poetry. It would begin with one of the oldest legends in the world,

the poignant tale of Philomela, that poor ravished girl who had her tongue

cut out and was changed into the nightingale, which laments in darkness

but nonetheless expresses its story. The tale reverberates through all

of Greco-Roman literature. Ovid gave it a poignant rendering in Metamorphoses,

and it echoed down the centuries from Shakespeare ( Titus Andronicus)

to Matthew Arnold ("Philomela") and T. S. Eliot ("The Waste Land").

One of my favorite poems about "spring's messenger"

is by Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentine fabulist, who may never have heard

a nightingale, and yet, through poetry, had a lifelong relationship with

the unseen bird.

To THE NIGHTINGALE

Out of what secret English summer evening

or night on the incalculable Rhine,

lost among all the nights of my long night,

could it have come to my unknowing ear,

your song, encrusted with mythology,

nightingale of Virgil and the Persians?

Perhaps I never heard you, but my life

is bound up with your life, inseparably.

The symbol for you was a wandering spirit

in a book of enigmas. The poet, El Marino,

nicknamed you the "siren of the forest";

you sing throughout the night of Juliet

and through the intricate pages of the Latin

and from his pinewoods, Heine, that other

nightingale of Germany and Judea,

called you mockingbird, firebird, bird of mourning.

Keats heard your song for everyone, forever.

There is not one among the shimmering names

people have given you across the earth

that does not seek to match your own music,

nightingale of the dark. The Muslim dreamed you

in the delirium of ecstasy,

his breast pierced by the thorn of the sung rose

you redden with your blood. Assiduously

in the black evening I contrive this poem,

nightingale of the sands and all the seas,

that in exultation, memory, and fable,

you burn with love and die in liquid song.

(TRANSLATED BY ALASTAIR REID)

Auden

Những dòng mà Edward Mendelson

viết về sự sửa thơ của Auden, quái làm sao, “mắc mớ gì

đó”, với thái độ không sửa thơ, và thái

độ, không “viết lại”, hay “lại viết”, sau khi ra tù VC

Most criticism, however, has taken a censorious view

of Auden's revisions, and the issue is an important one because behind

it is a larger dispute about Auden's theory of poetry.

In making his revisions, and in justifying them as he did,

Auden was systematically rejecting a whole range of modernist assumptions

about poetic form, the nature of poetic language, and the effects of

poetry on its audience. Critics who find the changes deplorable generally

argue, in effect, that a poet loses his right to revise or reject his

work after he publishes it-as if the skill with which he brought his

poems from their early drafts to the point of publication somehow left

him at the moment they appeared, making him a trespasser on his own work

thereafter. This argument presupposes the romantic notion that poetic form

is, or ought to be, "organic," that an authentic poem is shaped by its

own internal forces rather than by the external effects of craft; versions

of this idea survived as central tenets of modernism. In revising his poems,

Auden opened his workshop to the public, and the spectacle proved unsettling,

especially as his revisions, unlike Yeats', moved against the current

of literary fashion. In the later part of his career, he increasingly

called attention in his essays to the technical aspects of verse, the details

of metrical and stanzaic construction-much as Brecht had brought his

stagehands into the full view of the audience. The

goal in each case was to remove the mystery that surrounds works of

art, to explode the myth of poetic inspiration, and to deny any special

privileges to poetry in the realm of language or to artists in the realm

of ethics.

Critics mistook this attitude as a "rejection" of poetry…

Cái câu Gấu gạch dưới, giải thích

thái độ của TTT, khi không viết nữa, và nó

mắc mớ tới vấn đề đạo hạnh của nghệ sĩ.

Bài thơ hiển hách nhất của Auden, với riêng

Gấu, và tất nhiên, với Brodsky – ông đọc nó khi

bị lưu đầy nội xứ ở 1 nông trường cải tạo, và khám phá

ra cõi thơ của chính ông! – là bài tưởng

niệm Yeats

http://tanvien.net/Dayly_Poems/Auden.html

In Memory of W B. Yeats

(d.January 1939)

Bạn thì cũng cà

chớn như chúng tớ: Tài năng thiên bẩm của bạn sẽ

sống sót điều đó, sau cùng;

Nào cao đường minh

kính của những mụ giầu có, sự hóa lão của

cơ thể.

Chính bạn; Ái

Nhĩ Lan khùng đâm bạn vào thơ

Bây giờ thì

Ái Nhĩ Lan có cơn khùng của nó, và

thời tiết của ẻn thì vưỡn thế

Bởi là vì

thơ đếch làm cho cái chó gì xẩy ra: nó

sống sót

Ở trong thung lũng của

điều nó nói, khi những tên thừa hành sẽ

chẳng bao giờ muốn lục lọi; nó xuôi về nam,

Từ những trang trại riêng

lẻ và những đau buồn bận rộn

Những thành phố

nguyên sơ mà chúng ta tin tưởng, và chết

ở trong đó; nó sống sót,

Như một cách ở

đời, một cái miệng.

Thời gian vốn không khoan

dung

Đối với những con người can đảm và thơ ngây,

Và dửng dưng trong vòng một tuần lễ

Trước cõi trần xinh đẹp,

Thờ phụng ngôn ngữ và

tha thứ

Cho những ai kia, nhờ họ, mà nó sống;

Tha thứ sự hèn nhát và trí trá,

Để vinh quang của nó dưới chân chúng.

Thời gian với nó

là lời bào chữa lạ kỳ

Tha thứ cho Kipling và những quan điểm của ông

ta

Và sẽ tha thứ cho… Gấu Cà Chớn

Tha thứ cho nó, vì nó viết bảnh quá!

Trong ác mộng của bóng

tối

Tất cả lũ chó Âu Châu sủa

Và những quốc gia đang sống, đợi,

Mỗi quốc gia bị cầm tù bởi sự thù hận của

nó;

Nỗi ô nhục tinh thần

Lộ ra từ mỗi khuôn mặt

Và cả 1 biển thương hại nằm,

Bị khoá cứng, đông lạnh

Ở trong mỗi con mắt

Hãy đi thẳng, bạn thơ

ơi,

Tới tận cùng của đêm đen

Với giọng thơ không kìm kẹp của bạn

Vẫn năn nỉ chúng ta cùng tham dự cuộc chơi

Với cả 1 trại thơ

Làm 1 thứ rượu vang của trù eỏ

Hát sự không thành công của con

người

Trong niềm hoan lạc chán chường

Trong sa mạc của con tim

Hãy để cho con suối chữa thương bắt đầu

Trong nhà tù của những ngày của anh

ta

Hãy dạy con người tự do làm thế nào

ca tụng.

February 1939

W.H. Auden

Thơ Charles Simic

BEDTIME STORY

When a tree falls in a forest

And there's no one around

To hear the sound, the poor owls

Have to do all the thinking.

They think so hard they fall off

Their perch and are eaten by ants,

Who, as you already know, all look like

Little Black Riding Hoods.

Chuyện dỗ ngủ

Khi một cái cây té xuống ở trong rừng

Chẳng có ai ở đó để mà nghe tiếng cây

đổ

Thành thử những con cú đáng thương đành

phải cáng đáng mọi suy tư

Chúng suy tư khủng quá

Thế là rớt mẹ xuống đất

Và bị lũ kiến làm thịt

Chúng, như bạn quá rành tỏ mọi điều

Tất cả thì giống như

Những cô bé quàng khăn đen.

PRIMER

This kid got so dirty

Playing in the ashes

When they called him home,

When they yelled his name over the ashes,

It was a lump of ashes

That answered.

Little lump of ashes, they said,

Here's another lump of ashes for dinner,

To make you sleepy,

And make you grow strong.

Vỡ Lòng

Thằng bé này dơ quá

Chơi với tro

Khi kêu về nhà

Khi kêu tên nó qua đống tro

Đống tro trả lời

Đống tro nhỏ kia ơi

Họ gọi

Đây có một đống nho nhỏ khác nữa

Dành cho bữa tối

Để cho mi ngủ ngon

Để cho mi chóng lớn

WHISPERS

IN THE NEXT ROOM

The hospital barber, for instance,

Who shaves the stroke victims,

Shaves lunatics in strait-jackets,

Doesn't even provide a mirror,

Is a widower, has a dog waiting

At home, a canary from a dimestore ...

Eats beans cold from a can,

Then scrapes the bottom with his spoon ...

Says: No one has seen me today,

Oh Lord, as I too have seen

No one, not even myself,

Bent as I was, intently, over the razor.

Những tiếng thì thầm

Trong phòng kế bên

Tên thợ cạo bịnh viện, thí dụ,

Kẻ cạo đầu,

Những nạn nhân chết vì đứng tim

Những tên khùng trong những chiếc áo strait-jackets

Đếch thèm ban cho họ 1 tấm gương

Là 1 tên góa vợ, có 1 con chó,

đợi hắn ở nhà,

Gần 1 tiệm chuyên bán đồ rẻ tiền…

Con chó chuyên ăn đậu, đóng lon, để lạnh

Rồi đập đập cái đáy lon, với cái muỗng của nó….

Nè, nghe nè,

Đếch ai nhìn thấy Gấu bữa nay

Ôi Chúa ơi là Chúa ơi!

Gấu cũng chẳng nhìn thấy ai, ngay cả chính Gấu

Thằng khốn cúi lom khom

Đưa mẹ cái cổ của nó

Vô lưỡi dao cạo!

POEM

My father writes all day, all night:

Writes while he sleeps, writes in his coffin.

It's nice and quiet in our house.

You can see the specks of dust in the sunlight.

I look at times over his shoulders

At all that whiteness. The snow is falling,

As you'd expect. A drop of ink

Getsburied easily, like a footprint.

I, too, would get lost but there's his shadow

On the wall, like a perched owl.

There's the sound of his pen

And the bottle on the table sunk in thought.

When the bottle empties

His great dark hand

Bigger than the earth

Feels for the moon's spigot

Note: Bài thơ này, nhớ là có 1 tay, trong

1 cuốn tuyển tập những bài phê bình viết về Simic,

đi 1 đường rất ư là OK, về bài thơ, tất nhiên, nhưng

còn về ông bố của Simic.

Simic cũng đã trải qua cái cảnh chờ bố, khi ông

bị Gestapo bắt - như ông bố của Gấu, đi hội họp, làm cách

mạng, với 1 đấng học trò, Trùm 1 băng đảng “phản cách

mạng”, và bị hắn làm thịt, ông bố của Simic may mắn

hơn, được thả…

Có thể nói thơ của Simic, bị ám ảnh bởi những

ngày thơ ấu Nazi, và ăn bom, ăn pháo kích…

Bài intro, cho bài thơ Đế Quốc của Những Giấc Mơ, của

Milosz, trong cuốn A Book of Luminous Things, là nói

về ám ảnh này:

Một giấc mơ có thể biến đổi 1 khoảnh

khắc đã từng sống, 1 lúc nào đó, thành

1 phần của ác mộng. Charles Simic, 1 nhà thơ Mẽo gốc Serbia,

nhớ lại thời kỳ Nazi đô hộ xứ của ông. Một xen thời thơ ấu được

"để trong khuây khoả" - put in relief - như là hiện tại, nhưng

đâu còn nữa, nhưng, vào lúc thi sĩ viết, trở lại

hoài hoài trong những giấc mơ.

Nói 1 cách khác, nó có 1 hiện

tại của riêng nó, theo 1 kiểu mới mẻ nào đó,

trong trang đầu tiên của 1 cuốn nhật ký của những giấc mơ.

(1)

A

dream may transform a moment lived once, at one time, and change it

into part of a nightmare. Charles Simic, an American poet born in Serbia,

remembers the time of the German occupation in his country. This scene

from childhood is put in relief as the present which is no more, but

which now, when the poet writes, constantly returns in dreams. In other

words, it has its own present, of a new kind, on the first page of a

diary of dreams.

EMPIRE OF DREAMS

On the first page of my dream book

It's always evening

In an occupied country.

Hour before the curfew.

A small provincial city.

The houses all dark.

The store-fronts gutted.

I am on a street corner

Where I shouldn't be.

Alone and coatless

I have gone out to look

For a black dog who answers to my whistle.

I have a kind of Halloween mask

Which I am afraid to put on.

Charles Simic

ĐẾ QUỐC CỦA NHỮNG GIẤC MƠ

Ở trang đầu cuốn sách mơ của tôi

Thì luôn luôn là 1 buổi chiều tối

Trong 1 xứ sở bị chiếm đóng.

Giờ, trước giới nghiêm.

Một thành phố tỉnh lẻ.

Nhà cửa tối thui

Mặt tiền cửa tiệm trông chán ngấy.

Tôi ở 1 góc phố

Đúng ra tôi không nên có mặt ở

đó.

Co ro một mình, không áo choàng

Tôi đi ra ngoài phố để kiếm

Một con chó đen đã đáp lại tiếng huýt

gió của tôi.

Tôi mang theo 1 cái mặt nạ Halloween

Nhưng lại ngại không dám đeo vô.

(1)

Đây là sự khác biệt rất khác biệt, của

thơ Simic, và những người như ông, Mẽo di dân, Mẽo

tị nạn…. với những tên Mỹ gốc Mít, cũng lưu vong như ông.

Thơ của lũ này, cực kỳ nhơ bẩn, theo cái nghĩa, quên

mẹ quá khứ, không chỉ quên, mà còn nói

ngược hẳn lại, chúng ông vượt qua được Cái Ác,

bất cứ Cái Ác, dù Nazi, dù Gulag, dù

Ác Bắc Kít rồi!

Thơ của Simic, khi viết về đề tài này, có những

bài cực kỳ thê lương, dù chỉ 1 câu thôi.

Peter Stitt, trong

“Imagination in the Ascendant: Charles Simic's Austerities", in

trong Essays on the Poetry, phán: Simic

nổi tiếng vì cái trò “chỉ là đồ chơi”,

với cái độc ác của con người , Simic is famous for his handling

of human cruelty.

Và ông dẫn chứng bằng bài thơ trên, Nan Đề, tạm dịch Rough Outline.

Gấu rất sợ thơ Simic, thời gian đầu đọc ông. Bây

giờ thì quen, hoặc bớt sợ rồi!

Bạn đọc bài thơ sau đây

mà chẳng thấy sợ sao?

Một tay phê

bình phán:

Charles Simic là một câu [C.S. is a sentence)

Quả thế thật:

Touching me, you

touch

The country that has exiled you

The Wind

Cả bài thơ,

chỉ có mỗi một câu.

Gió

Đụng ta, mi đụng

Cái xứ sở đã đầy mi lưu vong

Simic không

thể quên Đế Quốc của Giấc Mơ, chúng ta không thể quên…

Cái Ác Bắc Kít, nhờ ông! Nhiều bài thơ

của ông, đọc 1 phát, là ra xứ Mít, khủng khiếp

thế. Thí dụ bài Vila del Tritone, mà, nhờ Lisa Sack

Gấu nhận ra, đây chính là tình cảnh của Gấu, khi

trở lại Sài Gòn, hoặc Hà Nội...

Nhìn

một phát, là tôi cảm thấy quặn đau thốn dế

Mình có thể sinh ra tại căn nhà này,

Và bị bỏ mặc, không người an ủi.

Simic

VIA DEL TRITONE

In Rome, on the street of that name,

I was walking alone in the sun

In the noonday heat, when I saw a house

With shutters closed, the sight of which

Pained me so much, I could have

Been born there and left inconsolably.

The ochre walls, the battered old

door

I was tempted to push open and didn't,

Knowing already the coolness of the entrance,

The garden with a palm tree beyond,

And the dark stairs on the left.

Shutters closed to cool shadowy rooms

With impossibly high ceilings,

And here and there a watery mirror

And my pale and contorted face

To greet me and startle me again and again.

"You found what you were looking for,"

I expected someone to whisper.

But there was no one, neither there

Nor in the street, which was deserted

In that monstrous heat that gives birth

To false memories and tritons.

Charles Simic

VIA DEL TRITONE

Ở Rome, trên con phố cũng có

tên đó

Tôi đi bộ một mình trong ánh mặt trời

Nóng ban trưa, và tôi nhìn thấy một căn

nhà

Những tấm màn cửa thì đều đóng,

Nhìn một phát, là tôi cảm thấy quặn đau

thốn dế

Mình có thể sinh ra tại căn nhà này,

Và bị bỏ mặc, không người an ủi.

Tường màu gạch son, cửa cũ,

rệu rạo

Tôi tính đẩy cửa, nhưng không làm

Biết rõ cái lạnh lẽo sau cánh cửa, lối dẫn vào

căn nhà,

Căn vườn với 1 cây sồi quá nó,

Và những cầu thang u tối ở phía trái.

Rèm cửa đóng dẫn tới

những căn phòng lờ mờ

Trần hơi bị thật là cao

Và đâu đó, là một cái gương long

lanh nước

Và khuôn mặt của tôi nhợt nhạt, méo mó

Ðón chào tôi, và làm tôi

giật mình hoài

"Mi kiếm ra cái mà mi

tính kiếm?"

Tôi uớc ao có ai đó thì thào

Nhưng làm đếch gì có một ai

Ðếch có ai, cả ở trên con phố hoang vắng

Vào cái giờ nóng khùng điên

Làm đẻ ra những hồi ức dởm

Và những con quái vật nửa người nửa cá

One poem is unlike any I've ever read-if

it had appeared in the lineup, I might not have recognized it as Simic's.

"Via Del Tritone" juxtaposes no surreal images. It begins simply:

In Rome, on the street of that name,

I was walking alone in the sun

In the noonday heat, when I saw a house

With shutters closed, the sight of which

Pained me so much, I could have

Been born there and left inconsolably.

Simic goes on to describe the interior,

as he imagines it, a garden with a palm tree, dark stairs leading to cool

rooms with high ceilings. "'You found what you were looking for,' / I expected

someone to whisper." Never, in his previous work, has Simic expressed the

pain of his exile in such a straightforward way. His outsider's status was

always an advantage, teaching him that life was unpredictable and that anything

might happen, as the antic careening of his poetry suggests. In this poem

his pain and loss blossom like the most fragile of tea roses. He hasn't

found what he was looking for. How can you reclaim a childhood that never

was? Simic, unlike Nabokov, has no Eden to recall. His are "false memories,"

phantasms of heat. And as the war rages on in the place where his childhood

should have been, salvage becomes less possible. The poet's cries flutter

up from the page: "Help me to find what I've lost, / If it was ever, however

briefly, mine."

Lisa Sack: Charles the Great: Charles

Simic’s A Wedding in Hell

Bài thơ này thật khác

với những bài thơ của Simic. Không có sự trộn lẫn những

hình ảnh siêu thực.

Via Del Tritone mở ra, thật giản dị:

Ở Rome, trên con phố cũng có

tên đó

Tôi đi bộ một mình trong ánh mặt trời

Nóng ban trưa, và tôi nhìn thấy một căn

nhà

Những tấm màn cửa thì đều đóng,

Nhìn một phát, là tôi cảm thấy quặn đau

thốn dế

Mình có thể sinh ra tại căn nhà này,

Và bị bỏ mặc, không người an ủi.

Sau đó, tác giả tiếp

tục tả bên trong căn nhà, như ông tưởng tượng ra…Chưa

bao giờ, trong những tác phẩm trước đó, Simic diễn tả nỗi đau

lưu vong một cách thẳng thừng như ở đây. Cái vị thế

kẻ ở ngoài lề luôn luôn là lợi thế, nó dạy

ông rằng đời thì không thể tiên liệu trước được và

chuyện gì cũng có thể xẩy ra. Ở đây, nỗi đau, sự mất

mát của ông nở rộ như những cánh trà hồng mảnh

mai nhất. Ông làm sao kiếm thấy cái mà ông

kiếm, một tuổi thơ chẳng hề có? Simic, không như Nabokov, chẳng

hề có Thiên Ðàng để mà hồi nhớ. Chỉ là

hồi nhớ dởm, do cái nóng khùng điên tạo ra.

Và chiến tranh tàn khốc xẩy ra ở cái nơi đáng

lý ra tuổi thơ xẩy ra, làm sao có cứu rỗi? Và

tiếng la thét của nhà thơ vọng lên từ trang giấy:

Hãy giúp tôi tìm cái mà tôi

đã mất/Cho dù nhỏ nhoi, cho dù chốc lát, cái

tí ti đã từng là của tôi.

Bài này,

đọc lại, tuyệt thật.

NQT [20.6.2013]

Bài này, thì đúng là quang

cảnh ngày 30 Tháng Tư 1975

CAMEO APPEARANCE

I had a small, nonspeaking part

In a bloody epic. I was one of the

Bombed and fleeing humanity.

In the distance our great leader

Crowed like a rooster from a balcony,

Or was it a great actor

Impersonating our great leader?

That's me there, I said to the

kiddies.

I'm squeezed between the man

With two bandaged hands raised

And the old woman with her mouth open

As if she were showing us a tooth

That hurts badly. The hundred

times

I rewound the tape, not once

Could they catch sight of me

In that huge gray crowd,

That was like any other gray crowd.

Trot off to bed, I said finally.

I know I was there. One take

Is all they had time for.

We ran, and the planes grazed

our hair,

And then they were no more

As we stood dazed in the burning city.

But, of course, they didn't film that.

Charles Simic

Cameo Apperance: Sự xuất hiện của 1 nhân

vật nổi tiếng, trong 1 phim….

CAMEO APPEARANCE

Tớ có cái phần

nhỏ mọn, không nói

Trong cuốn sử thi đầy máu của dân tộc tớ.

Tớ là một trong cái nhân loại

Bị bom, oanh tạc, pháo kích, và bỏ chạy té

đái!

Từ xa, vị lãnh đạo của chúng tớ lúc đó,

hình như là Sáu Dân thì phải

Gáy như 1 con gà trống, từ ban công dinh Độc Lập

Hay là thằng khốn nào đóng vai Sáu Dân

vĩ đại?

“Tớ đó”, tớ nói

với lũ con nít

Tớ bẹp dí, giữa một người đàn ông

Hai tay băng bó, cùng giơ lên

[Sao giống TCS quá, khi chào mừng Sáu Dân,

sau khi ca Nối Vòng Tay Lớn?]

Và một bà già miệng há hốc

Như thể bà muốn chỉ cho coi một cái răng của bả.

Đau thật. Nhức nhối thật.

Hàng trăm lần, tớ coi đi coi lại You tube,

Không chỉ 1 lần

Liệu họ nhận ra tớ không nhỉ,

Trong cái đám đông ở Dinh Độc Lập bữa đó?

Thì cũng như mọi đám đông xám xịt,

Bè lũ Cách Mạng 30 Tháng Tư,

Đứa nào cũng có 1 cái băng đỏ ở cánh tay!

Thôi đi ngủ, tớ sau cùng

phán

Tớ biết, có tớ ở đó.

Một cú [cameo appearance]

Họ đâu có thì giờ, 1 cú là đủ rồi.

Chúng tớ chạy, và những chiếc trực thăng thổi tóc chúng tớ,

Như muốn giật chúng ra khỏi đầu.

Và rồi chẳng còn gì hết

Chẳng còn máy bay trực thăng

Khi chúng tớ đứng bàng hoàng trong Sài

Gòn bốc cháy.

Nhưng, tất nhiên, lũ khốn VC có bao giờ cho nhân

loại coi cảnh này!

Hà, hà!

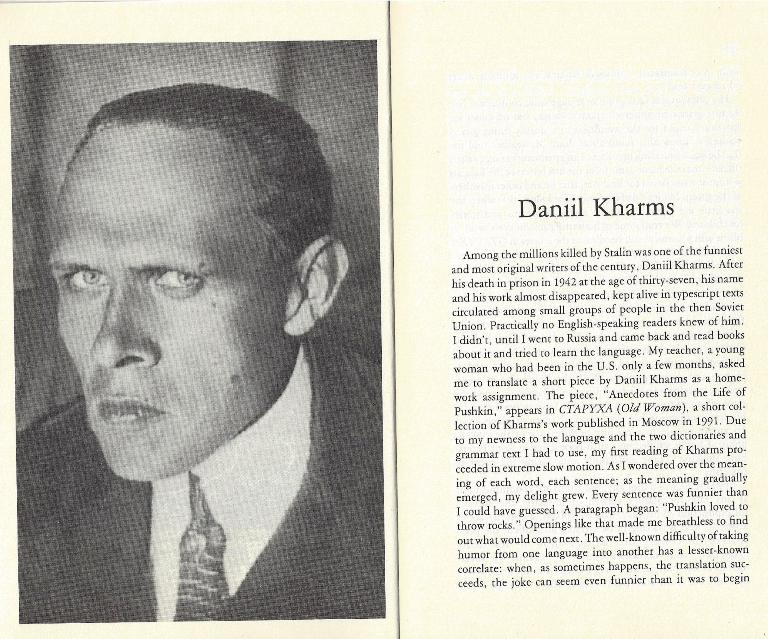

Bài Đọc Lịch Sử, tả cảnh ông cụ Gấu bị làm thịt

thời kỳ bắt đầu Cách Mạng Vẹm, 1945

READING HISTORY (1)

for Hans Magnus

At times, reading here

In the library,

I'm given a glimpse

Of those condemned to death

Centuries ago,

And of their executioners.

I see each pale face before me

The way a judge

Pronouncing a sentence would,

Marveling at the thought

That I do not exist yet.

With eyes closed I can hear

The evening birds.

Soon they will be quiet

And the final night on earth

Will commence

In the fullness of its sorrow.

How vast, dark, and impenetrable

Are the early-morning skies

Of those led to their death

In a world from which I'm entirely absent,

Where I can still watch

Someone's slumped back,

Someone who is walking away from

me

With his hands tied,

His graying head still on his shoulders,

Someone who

In what little remains of his life

Knows in some vague way about me,

And thinks of me as God,

As Devil.

Đọc Sử Ký

Gửi Hans Magnus

Đôi khi đọc ở đây

Tại thư viện

Tôi được đưa mắt nhìn

Những người bị kết án tử hình

Những thế kỷ đã qua

Và những đao phủ của họ

Tôi nhìn mỗi khuôn mặt nhợt nhạt

Cách ông tòa tuyên án

Lạ làm sao, là, tôi thấy mừng

Khi nghĩ rằng,

May quá, khi đó mình chưa ra đời!

Với cặp mắt nhắm tít,

tôi có thể nghe

Những con chim chiều tối

Chẳng mấy chốc, chúng sẽ mần thinh

Và đêm sau cùng trên trái đất

Sẽ bắt đầu

Trong trọn nỗi thống khổ của nó

Bao la, tối, không cách

nào xuyên thủng,

Là những bầu trời sáng sớm

Của những con người bị dẫn tới cái chết của họ

Trong một thế giới mà tôi thì hoàn toàn

vắng mặt

Từ cái chỗ của tôi, tôi vẫn có thể ngắm

Cái lưng lảo đảo,

Của một người nào đó,

Một người nào đó đang bước xa ra khỏi tôi

Với hai tay bị trói

Cái đầu xám của

người đó thì vẫn còn trên hai vai

Một người nào đó

Trong tí xíu thời gian còn lại của cuộc đời của

mình

Biết, một cách mơ hồ về tôi

Và nghĩ về tôi, như là Thượng Đế

Như là Quỉ

GCC đọc

bài này, là lại nhớ tới ông cụ của Gấu, bị chính

1 đấng học trò của ông, cho đi mò tôm.

Ở bên đó, ông sẽ nghĩ về Gấu, như là 1 tên

Bắc Kít khốn nạn, hay là 1 tên Bắc Kít đã

được Miền Nam… thuần hóa?

Note: Cũng sách xon. Cùng tay biên

tập Tuyển Tập Thơ, Edward Mendelson. Gấu thực sự choáng khi biết

Auden còn là 1 tay điểm sách, tác giả, phê

bình. Đọc loáng thoáng, trong bài viết về

Pope: Bài thơ bảnh nhất, độc nhất, đối với tôi, của Pope,

thất bại, là bài An Essay on Man. Nhưng thất bại, đấy, vưỡn

có những dòng thần sầu…

Thế rồi Auden nói vào tai Gấu, câu thơ thần sầu

của Pope:

Die of a rose in aromatic pain: Chết của 1 bông hồng, trong

cơn đau thơm lừng.

Bài về C.P. Cavafy, 1 “gay”, như ông, cũng thật tuyệt:

C. P. CAVAFY

Ever since I was first introduced to his poetry by

the late Professor R. M. Dawkins over thirty years ago, C. P. Cavafy

has remained an influence on my own writing; that is to say, I can think

of poems which, if Cavafy were unknown to me, I should have written quite

differently or perhaps not written at all.

30 năm trôi qua, kể từ khi được biết tới ông,

qua giáo sư đã mất R.M. Dawkins, Cavafy ảnh hưởng lên

cái viết của riêng tôi, điều này có

nghĩa:

Tôi nghĩ đến những bài thơ mà giả dụ rằng, tôi

không biết Cavafy là ai, thì tôi sẽ viết 1 cách

khác hẳn, hay có lẽ, đếch viết ra!

Ui chao, thần sầu. Mít cứt đái, đếch

thằng nào có Thầy, làm sao viết nổi 1 dòng đơn

giản như thế! NQT

Re: Auden sửa thơ.

Trong bài Giới thiệu Tuyển Tập Thơ của Auden,

tay biên tập khuyên chúng ta:

Probably the best way to get to know Auden's work is to read the early

versions first for their greater immediate impact, and the revised versions

afterwards for their greater subtlety and depth. For most readers this

book will be a First Auden, and the later collections are recommended as

a Second.

Cách tốt nhất, làm quen Auden, là

đọc những bài thơ đầu, sau đó, đọc thơ sửa, tinh tế hơn, sâu

lắng hơn...

Những dòng mà Edward Mendelson viết về

sự sửa thơ của Auden, quái làm sao, “mắc mớ gì đó”,

với thái độ không sửa thơ, và thái độ, không

“viết lại”, hay “lại viết”, sau khi ra tù VC

Most criticism, however, has taken a censorious view

of Auden's revisions, and the issue is an important one because behind

it is a larger dispute about Auden's theory of poetry.

In making his revisions, and in justifying them as he did, Auden was

systematically rejecting a whole range of modernist assumptions about poetic

form, the nature of poetic language, and the effects of poetry on its audience.

Critics who find the changes deplorable generally argue, in effect, that

a poet loses his right to revise or reject his work after he publishes it-as

if the skill with which he brought his poems from their early drafts to

the point of publication somehow left him at the moment they appeared, making

him a trespasser on his own work thereafter. This argument presupposes the

romantic notion that poetic form is, or ought to be, "organic," that an authentic

poem is shaped by its own internal forces rather than by the external effects

of craft; versions of this idea survived as central tenets of modernism.

In revising his poems, Auden opened his workshop to the public, and the spectacle

proved unsettling, especially as his revisions, unlike Yeats', moved against

the current of literary fashion. In the later part of his career, he increasingly

called attention in his essays to the technical aspects of verse, the details

of metrical and stanzaic construction-much as Brecht had brought his stagehands

into the full view of the audience. The goal in each case was to

remove the mystery that surrounds works of art, to explode the myth of poetic

inspiration, and to deny any special privileges to poetry in the realm of

language or to artists in the realm of ethics.

Critics mistook this attitude as a "rejection" of poetry…

Cái câu Gấu gạch dưới, giải thích

thái độ của TTT, khi không viết nữa, và nó mắc

mớ tới vấn đề đạo hạnh của nghệ sĩ.

Bài thơ hiển hách nhất của Auden, với riêng

Gấu, và tất nhiên, với Brodsky – ông đọc nó khi

bị lưu đầy nội xứ ở 1 nông trường cải tạo, và khám phá

ra cõi thơ của chính ông! – là bài tưởng

niệm Yeats

http://tanvien.net/Dayly_Poems/Auden.html

In Memory of W B. Yeats

(d.January 1939)

Bạn thì cũng cà

chớn như chúng tớ: Tài năng thiên bẩm của bạn sẽ sống

sót điều đó, sau cùng;

Nào

cao đường minh kính của những mụ giầu có, sự hóa lão

của cơ thể.

Chính

bạn; Ái Nhĩ Lan khùng đâm bạn vào thơ

Bây

giờ thì Ái Nhĩ Lan có cơn khùng của nó,

và thời tiết của ẻn thì vưỡn thế

Bởi là

vì thơ đếch làm cho cái chó gì xẩy ra:

nó sống sót

Ở trong

thung lũng của điều nó nói, khi những tên thừa hành

sẽ chẳng bao giờ muốn lục lọi; nó xuôi về nam,

Từ những

trang trại riêng lẻ và những đau buồn bận rộn

Những

thành phố nguyên sơ mà chúng ta tin tưởng, và

chết ở trong đó; nó sống sót,

Như một

cách ở đời, một cái miệng.

Thời gian vốn không khoan

dung

Đối với những con người can đảm và thơ ngây,

Và dửng dưng trong vòng một tuần lễ

Trước cõi trần xinh đẹp,

Thờ phụng ngôn ngữ và

tha thứ

Cho những ai kia, nhờ họ, mà nó sống;

Tha thứ sự hèn nhát và trí trá,

Để vinh quang của nó dưới chân chúng.

Thời gian

với nó là lời bào chữa lạ kỳ

Tha thứ cho Kipling và những quan điểm của ông ta

Và sẽ tha thứ cho… Gấu Cà Chớn

Tha thứ cho nó, vì nó viết bảnh quá!

Trong ác mộng của bóng

tối

Tất cả lũ chó Âu Châu sủa

Và những quốc gia đang sống, đợi,

Mỗi quốc gia bị cầm tù bởi sự thù hận của nó;

Nỗi ô nhục tinh thần

Lộ ra từ mỗi khuôn mặt

Và cả 1 biển thương hại nằm,

Bị khoá cứng, đông lạnh

Ở trong mỗi con mắt

Hãy đi thẳng, bạn thơ

ơi,

Tới tận cùng của đêm đen

Với giọng thơ không kìm kẹp của bạn

Vẫn năn nỉ chúng ta cùng tham dự cuộc chơi

Với cả 1 trại thơ

Làm 1 thứ rượu vang của trù eỏ

Hát sự không thành công của con người

Trong niềm hoan lạc chán chường

Trong sa mạc của con tim

Hãy để cho con suối chữa thương bắt đầu

Trong nhà tù của những ngày của anh ta

Hãy dạy con người tự do làm thế nào ca tụng.

February 1939

W.H. Auden

SCHOOL FOR

DARK THOUGHTS

At daybreak,

Little one,

I can feel the immense

weight

Of the books you carry.

Anonymous one,

I can hardly make you out

In that large crowd

On the frozen playground.

Simple one,

There are rulers and sponges

Along the whitewashed walls

Of the empty classroom.

There are windows

And blackboards,

One can only see through

With eyes closed.

Nhà trường cho những ý nghĩ u ám

Bình minh,

Hỡi chú nhỏ

Gấu có thể cảm thấy sức nặng chình trịch

của những cuốn sách

mà chú khệ nệ ôm theo

Nè, người vô danh,

Gấu thật khó lọc mi ra

Giữa đám đông

Trên sân chơi đóng băng

Người đơn giản kia,

Có những cây thước và những

miếng bọt biển

Dọc theo những bức tuờng vôi trắng

Của cái lớp học trống trơn.

Có những cửa sổ

Và những bảng đen

Bạn chỉ có thể nhìn qua

Mắt nhắm tịt

Trang kế, là Empire of Dreams

CHARLES SIMIC

1938-

A dream may transform a moment lived once, at one time,

and change it into part of a nightmare. Charles Simic, an American

poet born in Serbia, remembers the time of the German occupation in

his country. This scene from childhood is put in relief as the present

which is no more, but which now, when the poet writes, constantly returns

in dreams. In other words, it has its own present, of a new kind, on

the first page of a diary of dreams.

EMPIRE OF DREAMS

On the first page of my dream book

It's always evening

In an occupied country.

Hour before the curfew.

A small provincial city.

The houses all dark.

The store-fronts gutted.

I am on a street corner

Where I shouldn't be.

Alone and coatless

I have gone out to look

For a black dog who answers to my whistle.

I have a kind of Halloween mask

Which I am afraid to put on.

CHARLES SIMIC

Đế quốc của những giấc mơ

Ở trang đầu cuốn sách mơ của tôi

Thì luôn luôn là 1 buổi chiều

tối

Trong 1 xứ sở bị chiếm đóng.

Giờ, trước giới nghiêm.

Một thành phố tỉnh lẻ.

Nhà cửa tối thui

Mặt tiền cửa tiệm trông chán ngấy.

Tôi ở 1 góc phố

Đúng ra tôi không nên có

mặt ở đó.

Co ro một mình, không áo choàng

Tôi đi ra ngoài phố để kiếm

Một con chó đen đã đáp lại tiếng

huýt gió của tôi.

Tôi mang theo 1 cái mặt nạ Halloween

Nhưng lại ngại không dám đeo vô.

Bạn đọc phải đọc bài thơ, song song với Cõi

Khác của GNV thì mới thấy đã!

Đâu phải ‘vô tư’ mà Milosz chọn

bài này đưa vô Thơ Tuyển Thế Giới!

Ông cũng kinh qua kinh nghiệm... VC này

rồi!

Bởi thế, thay vì Cõi Mơ, Cõi Khác,

thì Simic gọi là Đế Quốc Của Những Giấc Mơ!

Đế Quốc Đỏ, Vương Quốc Ma Quỉ, và bây

giờ là Đế Quốc Của Những Giấc Mơ, Những Ác Mộng.

Hai dòng thơ chót mới tuyệt cú

mèo:

Cầm cái mặt nạ Ma trong tay mà không

dám đeo vô, vì sợ biến thành Quỉ.

Cũng chỉ là tình cờ: Trước khi xuống

phố, Gấu lục đúng 1 tờ NYRB cũ, Dec, 20, 2001, có

bài của Simic, viết về Milosz, thật tuyệt.

Và đó là lý do Gấu bệ cuốn

tuyển tập thơ thế giới, trên, sau khi cầm nó lên,

đọc loáng thoáng bài thơ của Simic.

Trong bài viết, Simic có trích,

những dòng thơ thật thần sầu của Milosz, thí dụ:

One life is not enough.

I'd like to live twice on this sad planet,

In lonely cities, in starved villages,

To look at all evil, at the decay of bodies,

And probe the laws to which the time was subject,

Time that howled above us like a wind.

Sống một đời chẳng đủ.

Giá mà có hai đời trên hành

tinh buồn này,

Để sống trong những thành phố cô đơn,

trơ trọi,

những làng mạc đói rạc,

Để nhìn đủ thứ ác,

đủ thứ thây người nát rữa ra,

Và để thấu được luật đời, mà

Thời gian là đề tài của nó.

Thời gian, hú như gió,

Trên đầu chúng ta.

Mấy bài sau đây, cũng quá OK.

BEDTIME STORY

When a tree falls in a forest

And there's no one around

To hear the sound, the poor owls

Have to do all the thinking.

They think so hard they fall off

Their perch and are eaten by ants,

Who, as you already know, all look like

Little Black Riding Hoods.

PRIMER

This kid got so dirty

Playing in the ashes

When they called him home,

When they yelled his name over the ashes,

It was a lump of ashes

That answered.

Little lump of ashes, they said,

Here's another lump of ashes for dinner,

To make you sleepy,

And make you grow strong.

WHISPERS

IN THE NEXT ROOM

The hospital barber, for instance,

Who shaves the stroke victims,

Shaves lunatics in strait-jackets,

Doesn't even provide a mirror,

Is a widower, has a dog waiting

At home, a canary from a dimestore ...

Eats beans cold from a can,

Then scrapes the bottom with his spoon ...

Says: No one has seen me today,

Oh Lord, as I too have seen

No one, not even myself,

Bent as I was, intently, over the razor.

POEM

My father writes all day, all night:

Writes while he sleeps, writes in his coffin.

It's nice and quiet in our house.

You can see the specks of dust in the sunlight.

I look at times over his shoulders

At all that whiteness. The snow is falling,

As you'd expect. A drop of ink

Getsburied easily, like a footprint.

I, too, would get lost but there's his shadow

On the wall, like a perched owl.

There's the sound of his pen

And the bottle on the table sunk in thought.

When the bottle empties

His great dark hand

Bigger than the earth

Feels for the moon's spigot.

History Book

A kid found its loose pages

On a busy street.

He stopped bouncing his ball

To run after them.

They fluttered in his hands

And flew off.

He could only glimpse

A few dates and a name.

At the outskirts the wind

Lost interest in them.

Some fell into the river

By the old railroad bridge

Where they drown kittens,

And the barge passes,

The one they named 'Victory'

From which a cripple waves.

Sách Sử Ký

Một chú bé kiếm thấy mấy tờ rời

Trên con phố bận người

Chú bèn ngưng đập trái banh

Và chạy đuổi

Chúng tuồn khỏi tay chú bé

Chuồn phấp phới

Chú chỉ thoáng nhìn thấy

Vài cái hẹn, và 1 cái tên

Tới vùng ngoại ô

Gió bèn chán mấy tờ rời

Thế là chúng bèn rớt xuống

Một con sông

Kế bên cây cầu cũ xì

Của 1 đường xe lửa

Nơi họ dìm lũ mèo con

Và con thuyền qua

Tên con thuyền, “Chiến Thắng”

Một anh què đứng trên thuyền

Bèn vẫy tay.

Drawn to Perspective

On a long block

Along which runs the wall

Of the House of Correction,

Someone has stopped

To holler the name

Of a son or a daughter.

Everything else in the world lies

As if in abeyance:

The warm summer evening;

The kid on roller skates;

The couple about to embrace

At the vanishing point.

Tình cờ K đọc thấy baì thơ này, hơi khác với

bài của anh . Không biết tại sao lại có sự khác

biệt như thế :

HISTORY BOOK

A kid found its loose pages

On a busy Street.

he stopped bouncing his ball

To run after them.

They fluttered from his hands

Like butterflies.

He could only glimpse

A few names, a date.

At the outskirts the wind

Took them high.

They were swept over

the used-tire dump

Into the grey river,

Where they drown kittens-

And the barge passes,

The one they name Victory

From which a cripple waves.

https://apeiron.tupacalos.es/?p=645

Trong này có nhiều bài cũng hay .

K

Tks.

Đây là 1 đề tài cực kỳ thú vị, vì,

cứ giả như Simic đã sửa, vì ấn bản của tôi, xưa

rồi.

Auden cũng hay sửa thơ, và Brodsky có lần nhận

xét, ông không thích cái vụ này,

nhớ đại khái, không biết có đúng không.

Tuy nhiên Gấu mới đọc 1 tập thơ của Auden, trong đó,

cái tay giới thiệu, nhận xét, phải sửa, vì hay

hơn nhiều, ngoài ra còn 1 lý do nữa, chính

đáng lắm - cũng quên rồi - để từ từ check lại.

Borges cũng hay sửa thơ, và có 1 tay khuyên,

bạn mê thơ Borges, thì nên học tiếng Tây

Ban Nha, vì những bài sửa đó tuyệt lắm!

TTT không hề sửa thơ, dù bị in sai. Câu

thơ "sáng mai thức dậy ‘khua’ nhiều nhớ thương… “, nhớ đại

khái, bị in sai là ‘khuya’ nhiều, ông biểu kệ mẹ

sai, ráng chịu, hà, hà!

Cái hiểu dịch sai, sái đi của Gấu, và

bị THMN khi đọc, khi dịch, sau này Gấu hiểu ra, tại mắt lé,

đúng như thế, quái đản thế.

Cú này còn ly kỳ hơn nhiều, Gấu có

mấy "giai thoại"- explications - về vụ này, từ từ tính!

Tks again.

Take Care

NQT

TB: Mấy bài thơ, 'nhiều bài cũng hay', đa số có

trên Tin Văn.

Simic có cái nick, được đời ban cho, “siêu

hình gia của bóng đêm”, quá tuyệt, đối với

ông.

Tay nào nghĩ ra cái nick này, khủng thật.

Gấu, sau này, giả như được đời ban cho 1 cái nick,

thì đúng là “thằng mắt lé”!

Giả như Gấu không lé, chắc không đọc sách,

viết sách, sống, yêu....như thế!

Bây giờ mới hiểu ra, Ông Trời quả có thương

Gấu. Không lé, là có 1 đời khác hẳn.

Cái vụ, nhờ lé, nhìn Gấu Cái ra

cô phù dâu, phải đến già Gấu mới hiểu ra

được!

Dates and name : ngày

tháng và tên ( thay vì cái hẹn )

Jun 13 at 1:37 AM

Ít nhất K

tìm thấy nguồn sách của bài này . Amazing :

|

|

|

POEMS

1967 - 1982. WEATHER FORECAST FOR UTOPIA & VICINITY [LTD SIGNED] ...

(POEMS

1967 - 1982. WEATHER FORECAST FOR UTOPIA & VICINITY [LTD SIGNED] poetry.

34625Simic, CharlesPOEMS 196...

|

|

|

|

HISTORY BOOK

A

kid found its loose pages

On a busy street

He stopped bouncing his ball

To run after them.

They

fluttered from his hands

Like butterflies.

He could only glimpse

A few names, a date.

At

the outskirts the wind

Took them high.

They were swept over the used-tire dump

Into the grey river,

Where

they drown kittens-

And the barge passes,

The one they name Victory

From wich a cripple waves.

From Weather Forecast

for Utopia & Vicinity, 1983

Tks

NQT

Ars Poetica?

By Czeslaw Milosz

Translated by Czeslaw Milosz and Lillian

Vallee

I have always aspired to a more spacious

form

that would be free from the claims of poetry

or prose

and would let us understand each other without

exposing

the author or reader to sublime agonies.

In the very essence of poetry there is something

indecent:

a thing is brought forth which we didn’t

know we had in us,

so we blink our eyes, as if a tiger had

sprung out

and stood in the light, lashing his tail.

That’s why poetry is rightly said to be

dictated by a daimonion,

though it’s an exaggeration to maintain

that he must be an angel.

It’s hard to guess where that pride of poets

comes from,

when so often they’re put to shame by the

disclosure of their frailty.

What reasonable man would like to be a city

of demons,

who behave as if they were at home, speak

in many tongues,

and who, not satisfied with stealing his

lips or hand,

work at changing his destiny for their convenience?

It’s true that what is morbid is highly

valued today,

and so you may think that I am only joking

or that I’ve devised just one more means

of praising Art with the help of irony.

There was a time when only wise books were

read,

helping us to bear our pain and misery.

This, after all, is not quite the same

as leafing through a thousand works fresh

from psychiatric clinics.

And yet the world is different from what

it seems to be

and we are other than how we see ourselves

in our ravings.

People therefore preserve silent integrity,

thus earning the respect of their relatives

and neighbors.

The purpose of poetry is to remind us

how difficult it is to remain just one person,

for our house is open, there are no keys

in the doors,

and invisible guests come in and out at

will.

What I'm saying here is not, I agree, poetry,

as poems should be written rarely and reluctantly,

under unbearable duress and only with the

hope

that good spirits, not evil ones, choose

us for their instrument.

Berkeley, 1968

Ars Poetica?

Tôi luôn luôn thèm một

thể thức rộng rãi hơn

Nó sẽ rủ bỏ ba thứ đòi hỏi nhảm

nhí của, thơ hay văn xuôi, và

Nó sẽ làm cho chúng ta, người

nọ hiểu người kia hơn, mà

Không cần bày ra, hoặc xô đẩy,

tác giả hay người đọc

Tới những thống khổ siêu phàm

Ở trong cái yếu tính rất ư là

yếu tính, của thơ, có cái rất ư là

thô bỉ, trơ trẽn, đếch ra làm sao cả

1 điều chường ra đó, cái điều mà

chúng ta cũng không hề biết, nó có

ở trong chúng ta

Và nó là chúng ta

lòa con mắt

Như thể có 1 hổ từ đâu phóng

ra

Và sừng sững trong ánh sáng,

quật quật cái đuôi.

Chính là do như thế mà thơ

được coi như là được quỉ phán, bảo, ra lệnh…

Tuy nhiên thật cường điệu khi coi thứ quỉ

ma này phải là 1 thiên thần

Thật khó mà biết được niềm kiêu

hãnh của những thi sĩ tới từ đâu

Bởi là vì thường xuyên lũ

này áo thụng vái nhau, bày ra nỗi

tủi hổ là sự bạc nhược của chúng.

Điều mà 1 con người biết điều mong muốn,

sẽ là một thành phố của quỉ

Chúng xử sự như thể chúng đang ở

nhà, nói nhiều thứ tiếng, và

Không hài lòng vì chôm

chĩa, môi hoặc tay

Bèn làm cái việc là,

thay đổi số phận của chúng, coi số phận là tiện lợi?

Rõ ràng là, vào lúc

này, thật ghê tởm khi… ghê tởm được đánh

giá cao

Và như thế, có thể là bạn

nghĩ, tôi đang nói đùa, nói rỡn chơi,

Hay tôi phịa ra thêm 1 phương tiện

Hay ca ngợi Nghệ Thuật với sự trợ giúp

của tiếu lâm, khôi hài

Đó là 1 thời mà chỉ những

sách minh triết được viết ra

Giúp chúng ta chịu đựng được nỗi

đau và sự khốn cùng

Điều này, nói cho cùng, thì

là như nhau

Như lật lật cả ngàn tác phẩm mới

tinh, từ những bịnh viện tinh thần, tức nhà thương điên

Dù thế nào, thế giới khác

hẳn, điều xem ra nó có thể

Và chúng ta thì khác,

chúng ta nhìn chúng ta, theo kiểu gầm rú,

hò hét

Con người từ đó, bèn chọn sự nguyên

vẹn thầm lặng

Nhờ vậy được bà con lối xóm kính

nể

Mục đích của thơ ca là để nhắc nhở

chúng ta

Thật khó khăn luôn luôn, mãi

mãi, chỉ là 1 người

Bởi là vì nhà của chúng

ta mở rộng cửa, không có khóa

Và những người khách vô hình

ra vô thoải mái

Điều mà tôi muốn nói ở đây,

thì không phải, tôi đồng ý, thơ

Khi mà những bài thơ thì nên

được viết,

Hiếm hoi đi, họa hoằn ra, ngần ngại mãi ra

Dưới cái sự cứng rắn không thể nào

chịu nổi

Và chỉ với hy vọng

Rằng

Chính là những tinh anh, tính

khí tốt, “nhân hậu và cảm động”… -

Không phải lũ quỉ ma, bộ lạc Cờ Lăng, hay

Bắc Bộ Phủ -

Chọn chúng ta

Như là dụng cụ của chúng.

HUẾ

HUE IS A pleasant little town with

something of the leisurely air of a cathedral city

in the West of England, and though the capital of an empire

it is not imposing. It is built on both sides of a wide river,

crossed by a bridge, and the hotel is one of the worst in

the world. It is extremely dirty, and the food is dreadful;

but it is also a general store in which everything is provided

that the colonist may want from camp equipment and guns, women's

hats and men's reach-me-downs, to sardines, pate de foie gras,

and Worcester sauce; so that the hungry traveler can make up

with tinned goods for the inadequacy of the bill of fare. Here the

inhabitants of the town come to drink their coffee and fine in the

evening and the soldiers of the garrison to play billiards. The French

have built themselves solid, rather showy houses without much regard

for the climate or the environment; they look like the villas of retired

grocers in the suburbs of Paris.

The

French carry France to their colonies just as the English

carry England to theirs, and the English, reproached for

their insularity, can justly reply that in this matter

they are no more singular than their neighbors. But not even

the most superficial observer can fail to notice that there

is a great difference in the manner in which these two nations

behave towards the natives of the countries of which they have

gained possession. The Frenchman has deep down in him a persuasion

that all men are equal and that mankind is a brotherhood. He

is slightly ashamed of it, and in case you should laugh at him

makes haste to laugh at himself, but there it is, he cannot help

it, he cannot prevent himself from feeling that the native, black,

brown, or yellow, is of the same clay as himself, with the same

loves, hates, pleasures and pains, and he cannot bring himself

to treat him as though he belonged to a different species. Though

he will brook no encroachment on his authority and deals firmly

with any attempt the native may make to lighten his yoke, in the ordinary

affairs of life he is friendly with him without condescension

and benevolent without superiority. He inculcates in him his peculiar

prejudices; Paris is the centre of the world, and the ambition of

every young Annamite is to see it at least once in his life; you

will hardly meet one who is not convinced that outside France there

is neither art, literature, nor science. But the Frenchman

will sit with the Annamite, eat with him, drink with him, and play

with him. In the market place you will see the thrifty Frenchwoman with

her basket on her arm jostling the Annamite housekeeper and bargaining

just as fiercely. No one likes having another take possession of his

house, even though he conducts it more efficiently and keeps it in better

repair that ever he could himself; he does not want to live in the attics

even though his master has installed a lift for him to reach them; and

I do not suppose the Annamites like it any more than the Burmese that

strangers hold their country. But I should say that whereas the Burmese

only respect the English, the Annamites admire the French. When in course

of time these peoples inevitably regain their freedom it will be curious

to see which of these emotions has borne the better fruit.

The

Annamites are a pleasant people to look at, very small,

with yellow flat faces and bright dark eyes, and they look

very spruce in their clothes. The poor wear brown of the

color of rich earth, a long tunic slit up the sides, and trousers,

with a girdle of apple green or orange round their waists;

and on their heads a large flat straw hat or a small black turban

with very regular folds. The well-to-do wear the same neat turban,

with white trousers, a black silk tunic, and over this sometimes

a black lace coat. It is a costume of great elegance.

But

though in all these lands the clothes the people wear

attract our eyes because they are peculiar, in each everyone

is dressed very much alike; it is a uniform they wear, picturesque

often and always suitable to the climate, but it allows

little opportunity for individual taste; and I could not but

think it must amaze the native of an Eastern country visiting

Europe to observe the bewildering and vivid variety of costume

that surrounds him. An Oriental crowd is like a bed of daffodils

at a market gardener's, brilliant but monotonous; but an English

crowd, for instance that which you see through a faint veil of

smoke when you look down from above on the floor of a promenade concert,

is like a nosegay of every kind of flower. Nowhere in the East will

you see costumes so gay and multifarious as on a fine day in Piccadilly.

The diversity is prodigious. Soldiers, sailors, policemen, postmen,

messenger boys; men in tail coats and top hats, in lounge suits and

bowlers, men in plus fours and caps, women in silk and cloth and velvet,

in all the colors, and in hats of this shape and that. And besides this

there are the clothes worn on different occasions and to pursue different

sports, the clothes servants wear, and workmen, jockeys, huntsmen,

and courtiers. I fancy the Annamite will return to Hue and think

his fellow countrymen dress very dully.

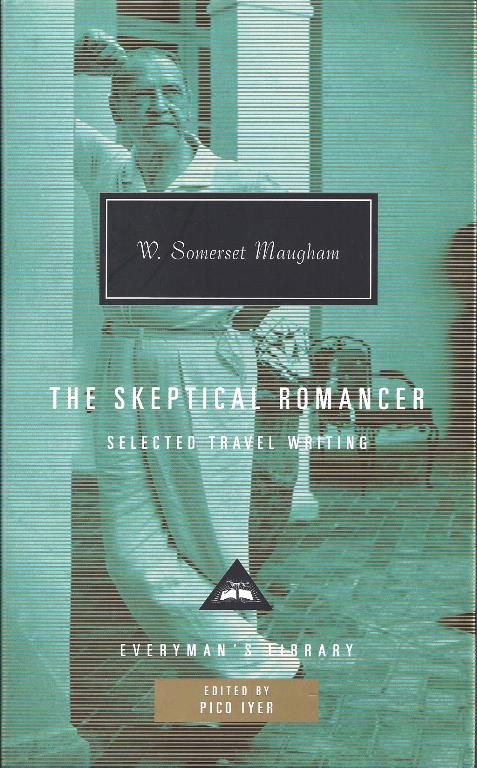

Somerset Maugham:

The Skeptical Romancer

The French carry France to their

colonies: Bạn

đọc bài viết, thì nhận ra 1 sự thực, tụi Tẩy đối

xử với miền đất Nam Kỳ, khác hẳn Bắc Kỳ: Chúng mang

nước Pháp tới cho họ. Ở xứ Bắc Kỳ, chúng sử dụng lũ

cường hào ác bá, y hệt sau này, Vẹm đối

xử với Ngụy, ở trong tù: Chúng dùng đám

tà lọt, ăng ten, làm điều cực ác thay cho chúng.

Ai đã từng đi tù VC thì rõ,

sức mấy 1 tên tù Ngụy được diện kiến 1 đấng cán

bộ quản giáo, đứng thật xa, cởi nón, mặt cúi

xuống đất…

Vào lúc sôi sục như hiện nay,

người dân Việt, cả nước, đang cố hất bỏ lũ Vẹm, truy diệt

Cái Độc Cái Ác của Vẹm.

Cầu Ơn Trên ban phước lành cho đất nước

của chúng ta. NQT (1)

(1)

A Burnt-Out Case.

Cuốn này, “Một trường hợp lụi tàn”, theo Phạm Việt

Cường cho biết, đã có bản tiếng Việt. Gấu sở dĩ chọn

nó, để toan tính mở ra cuốn truyện ngăn ngắn của

mình, là vì, Gấu cũng đã từng bị VC tính

thịt 1 cánh tay của mình, lần ăn mìn claymore

ở nhà hang nổi Mỹ Cảnh nơi bờ sông Sài Gòn,

mà còn là vì, hình như giống như

nhân vật chính trong truyện, Chúa đã bắt

kịp Gấu… 1 cách nào đó, sau khi cố tìm

cách làm thịt chính Gấu.

Còn nữa, cuốn A Burnt-Out Case, mắc mớ tới

niềm tin Ky Tô, mà những người như TTT, và

sau đó, lớp đàn em, trong có Gấu, không

có.

Trong “Lụi Tàn”, có 1 xen giống cái

cảnh TTT tả, trong Bếp Lửa, anh chàng Tâm đối diện

với Chúa, và bèn vặc, ông mà có

đầu thai làm người, thì cũng vô phương cứu loài

người, nhất là lũ Mít!

Trên đường về Lao, GCC mang theo hai cuốn, 1

là cuốn mới mua, của Kadare. Và 1 là cuốn A Burnt-Out

Case của Greene, tính mở ra 1 cú “tỉu thết”, chừng

trăm trang. Bằng 1 câu thuổng, từ Greene.

www.tanvien.net/Day_Notes/PXA_vs_Greene.html

" Trong một vài đường hướng, đây là

một cuốn sách tuyệt hảo đối với tôi - mặc dù

đề tài và sự quan tâm của nó, thì

rõ ràng thuộc về một cõi không tuyệt

hảo. Tôi đọc nó, lần đầu khi còn trẻ, dân

Ky tô, lớn lên ở Phi Châu, vào lúc

mà trại cùi còn phổ thông. Tôi còn

nhớ, lần viếng thăm cùng với mẹ tôi, một trại cùi

như thế, được mấy bà sơ chăm sóc, tại Ntakataka, nơi

hồ Lake Malawi. Và tôi sợ đến mất vía bởi cái

sự cử động dịu dàng đến trở thành như không có,

của những người cùi bị bịnh ăn mất hết cánh tay, y

hệt như được miêu tả ở trong cuốn tiểu thuyết: “Deo Gratias

gõ cửa. Querry nghe tiếng cào cào cánh

cửa của cái phần còn lại của cánh tay. Một xô

nước treo lủng lẳng ở cổ tay giống như một cái áo khoác,

treo ở cái núm trong tủ áo”.

Vào cái lúc tôi đọc nó,

thì tôi đang phải chiến đấu, như những người trẻ,

hay già, phải chiến đấu, và cũng không phải chỉ

ở Phi Châu, với những đòi hỏi về một niềm tin, khi mà

niềm tin này thì thực là "vô ích,

vô hại, vô dụng, vô can…", tại một nơi chốn, bất

cứ một nơi chốn, bị tai ương, bệnh tật, và cái chết

nhòm nhỏ, đánh hơi, quấy rầy, không phút

nào nhả ra.

Thành thử câu chuyện của Greene về một

gã Querry, một tay kiến trúc sư bảnh tỏng, tới xứ

Công Gô, chỉ để chạy trốn, và tìm ra một

thế giới, và có thể, Chúa bắt kịp anh ta đúng

ở đó, một câu chuyện như thế, làm tôi

quan tâm.

Trong một vài đường hướng, cuốn tiểu thuyết

có thể được đọc như một cuộc điều tra, về niềm tin hậu-Ky

tô, một toan tính để nhìn coi xem, cái

gì dấy lên từ tro than của thế kỷ trứ danh về cái

sự độc ác của nó…"

Ui chao, bạn đọc có thể mô phỏng đoạn

trên, và đi một đường “bốc thúi” trang Tin

Văn:

Trong một vài đường hướng, trang Tin Văn có

thể được đọc như là "… niềm tin hậu chiến Mít, một

cái gì dấy lên từ tro than của cuộc chiến trứ

danh vì Cái Ác Bắc Kít của nó."!

Nhưng, biết đâu đấy, Ky Tô giáo

đang lâm đại nạn tại nước Mít, là cũng ứng

vào cuộc "điều tra" này, của trang Tin Văn?

http://www.kundera.de/english/Info-Point/Interview_Roth/interview_roth.html

Roth: What you now call the laughter

of angels is a new term for the "lyrical attitude to life" of your

previous novels. In one of your books you characterize the era of

Stalinist terror as the reign of the hangman and the poet.

Kundera: Totalitarianism is not only hell but also the

dream of paradise-the age-old dream of a world where everybody lives

in harmony, united by a single common will and faith, without secrets

from one another. Andre Breton, too, dreamed of this paradise when he

talked about the glass house in which in which he longed to live. If

totalitarianism did not exploit these archetypes, which are deep inside

us all and rooted deep in all religions, it could never attract so many

people, especially during the early phases of its existence. Once the

dream of paradise starts to turn into reality, however, here and there

people begin to crop up who stand in its way, and so the rulers of paradise

must build a little gulag on the side of Eden. In the course of time this

gulag grows ever bigger and more perfect, while the adjoining paradise gets

ever smaller and poorer.

Roth: In your book, the great French poet Éluard

soars over paradise and gulag, singing. Is this bit of history that

you mention in the book authentic?

Kundera: After the war, Paul Éluard abandoned surrealism

and became the greatest exponent of what I might call the "poesy

of totalitarianism." He sang for brotherhood, peace, justice, better

tomorrows, he sang for comradeship and against isolation, for joy and

against gloom, for innocence and against cynicism. When in 1950 the

rulers of paradise sentenced Éluard's Prague friend, the surrealist

Zavis Kalandra, to death by hanging, Éuard suppressed his personal

feelings of friendship for the sake of supra-personal ideals and publicly

declared his approval of his comrade's execution. The hangman killed

while the poet sang…. And not just the poet. The whole period of Stalinist

terror was a period of collective lyrical delirium.

[….]

Roth & GCC:

Điều mà ông gọi là tiếng cười của những

thiên thần, là 1 từ khác, cho từ “thái độ

ướt át của cuộc đời”, của những cuốn trước đó, của ông.

Trong 1 cuốn, ông khắc họa thời khủng bố của Vẹm Bắc Kít

như là sự ngự trị trên ngai vàng Bắc Bộ Phủ, của

Văn Cao [đao phủ] và Văn Cao [nhà thơ] – Văn Cao đóng

cả hai vai, đao phủ và thi sĩ –

Kundera:

Chủ nghĩa toàn trị không chỉ là địa ngục

nhưng cũng còn là giấc mơ thiên đàng -

một giấc mơ già thật già về một thế giới, mọi người sống

trong hài hòa, được kết nối bởi 1 ước muốn chung và

niềm tin, không có bí mật giữa người này

với người kia… Nếu chủ nghĩa toàn trị không khai thác

những mẫu mã nằm sâu trong chúng ta, và trong

mọi tôn giáo thì nó không bao giờ

lôi cuốn nhiều người đến như thế, đặc biệt là trong những

giai đoạn khởi đầu của sự hiện hữu của nó. Một khi giấc mơ về

thiên đàng ló mòi, thì đâu đó,

con người bèn “làm thịt” những kẻ ngáng đường họ,

thế là 1 gulag xuất hiện, ngay bên lề thiên đàng.

Và thê thảm hơn, gulag thì ngày càng nở

rộ, phình mãi ra còn Thiên Đàng thì

mỗi lúc một teo lại!

..... Còn nữa, cuốn A Burnt-Out

Case, mắc mớ tới niềm tin Ky Tô, mà những người như TTT,

và sau đó, lớp đàn em, trong có Gấu, không

có.

Ui chao, về già thì Gấu nhận ra, cái

sự không có niềm tin ở 1 đấng Thượng Đế, ở nơi Gấu,

quả là cú trù ẻo khủng khiếp, không chỉ

với riêng Gấu, và, có thể nói, với toàn

giống Mít, nhất là Bắc Kít

Với lũ Mít, hoàn cảnh, đúng như câu

phán sau đây, Roth trích dẫn, trong bài

viết về Malamud:

“Mourning is a hard business,” Cesare said. “If people

knew, there’d be would be less death"

-From Malamud’s “Life Is Better Than Death” [1986]

Tưởng niệm đúng là 1 bi zí nét

khó nhai!

Bắc Kít, theo Gấu, không

hề biết “cầu nguyện” nghĩa là gì!

Điều này, Gấu ngộ ra, khi, lần về lại đất Bắc,

tới chỗ ông cụ Gấu bị tên học trò làm

thịt, nơi bãi sông Hồng… Gấu xuống xe, lui cui thắp

nhang cầu nguyện cho ông bố, trong khi bà chị ruột ngồi

tỉnh bơ trên xe. Bà thực sự không thể hiểu, và

làm được, 1 điều đơn giản như vậy. Thời của bà, bị VC

xóa sạch hồi ức, về tưởng niệm, cầu nguyện, hay quá nữa,

1 ý niệm về tôn giáo.

Bắc Kít không hề biết cầu

nguyện, và quá thế nữa, rất thù ghét

Ky Tô Giáo, hà, hà!

Thua xa đàn anh của chúng, là Liên

Xô, như Steiner nhận ra, trong bài viết Dưới Cái

Nhìn Đông Phương, và lạ thay, giấc mơ “Niên

Xô” này, cũng chính là của lũ Nam Kít,

thí dụ như, với Hồ Hữu Tường, trong khi chờ lên máy

chém của Diệm, mơ Đức Phật trở lại với Xứ Mít.

Lịch sử Nga là một lịch sử của đau khổ và

nhục nhã gần như không làm sao hiểu được, hay,

chấp nhận được. Nhưng cả hai - quằn quại vì đau khổ, và

ô nhục vì hèn hạ - nuôi dưỡng những cội rễ

một viễn ảnh thiên sứ, một cảm quan về một cái gì

độc nhất vô nhị, hay là sự phán quyết sáng

ngời. Cảm quan này có thể chuyển dịch vào một thành

ngữ “the Orthodox Slavophile”, với niềm tin của nó, là, Nga

là một xứ sở thiêng liêng theo một nghĩa thật là

cụ thể, chỉ có nó, không thể có 1 xứ nào

khác, sẽ nhận được những bước chân đầu tiên của Chúa

Ky Tô, khi Người trở lại với trần gian.

SCHOOL FOR

DARK THOUGHTS

At daybreak,

Little one,

I can feel the immense weight

Of the books you carry.

Anonymous one,

I can hardly make you out

In that large crowd

On the frozen playground.

Simple one,

There are rulers and sponges

Along the whitewashed walls

Of the empty classroom.

There are windows

And blackboards,

One can only see through

With eyes closed.

Nhà trường cho những ý nghĩ u ám

Bình minh,

Hỡi chú nhỏ

Gấu có thể cảm thấy sức nặng chình trịch của những cuốn

sách mà chú khệ nệ ôm theo

Nè, người vô danh

Gấu thật khó lọc mi ra

Giữa đám đông

Trên sân chơi đóng băng

Người đơn giản kia

Có những cây thước và những miếng bọt biển

Dọc theo những bức tuờng vôi trắng

Của cái lớp học trống trơn.

Có những cửa sổ

Và những bảng đen

Bạn chỉ có thể nhìn qua

Mắt nhắm tịt

Re My Lai & Seymour M. Hersh:

Tin Văn đã giới thiệu vụ này, lâu rồi, qua

mấy bài viết trên tờ NY. Nay, nhân cuốn hồi ký

mới ra mắt, có mấy tờ viết về nó.

Tờ Harper's đặt câu hỏi, tại sao tay ký giả trẻ này

lại cố gỡ rối thai đố My Lai, “How a young journalist untangled the riddle

of My Lai”.

Câu trả lời của Hersh thật thú, theo GCC:

Tôi là 1 tên ký giả may mắn sống sót

hoàng kim thời đại của báo chí.

Ai đã sống cuộc chiến Mít, thì hiểu câu

của ông: Ngụy rất quí và sợ báo chí.

Gấu dã chẳng kể là, chỉ 1 cái thẻ báo

chí của tờ quân đội VNCH, tờ Tiền Tuyến, do Phan Lạc Phúc

phát riêng cho GCC, mà Gấu đi lại suốt Sài

Gòn Chợ Lớn, có khi quá cả giờ giới nghiêm, khi,

gần như tối nào cũng mò tới nhà cô bạn, ở mãi

cuối đường Nguyễn Trãi.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/the-memory-of-my-lai

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/the-memory-of-my-lai

Chào Mừng World Cup

Carnet de lecture

par Enrique Vila-Matas

Note: Bài viết này, Vila-Matas viết cho BHD, như

bài thơ sau đây, Milosz mừng SN lần thứ 88 của Gấu. Tks

Both of U.

Và tôi nhớ ra rằng thì là

Giorgio Agamben đã từng giải thích, với mỗi một thằng

cu Gấu ở trong chúng ta, sẽ xẩy ra một cái ngày, mà

vào ngày đó, Bông Hồng Đen từ bỏ nó.

“Y hệt như là, bất thình lình, trong đêm

khuya, do tiếng động của một băng con nít đi qua cửa sổ của căn

phòng của bạn, và bạn cảm thấy, chẳng hiểu tại ra làm

sao, vì nguyên cớ nào, vị nữ thần, người nữ muôn

đời của bạn, từ bỏ bạn”.

Và nàng nói, “Bây giờ H.

hết lãng mạn rồi!”

Hình như, luôn luôn là, đối

với Gấu tôi, khi đến cõi đời này, là để tìm

kiếm trong giây lát, vị nữ thần của riêng Gấu tôi,

vị nữ thần của một đứa con nít, một thằng bé nhà

quê Bắc Kỳ, thằng bé đó chơi trò chơi phù

thuỷ thứ thiệt của giấc mơ.

I am like someone who just sees and doesn't pass away,

a lofty spirit despite his gray head and the afflictions

of age.

Saved by his amazement, eternal and divine.

Được cứu chuộc, nhờ cù lần, đời đời và thần thánh!

Seagull phán, nhẹ nhàng hơn: Nhân

hậu và cảm động.

Tks

Note:

To You, GCC

Czeslaw Milosz

FOR MY EIGHTY-EIGHTH BIRTHDAY

A city dense with covered passageways, narrow

little squares, arcades,

terraces descending to a bay.

And I, taken by youthful beauty,

bodily, not durable,

its dancing movement among ancient stones.

The colors of summer dresses,

the tap of a slipper's heel in centuries-old lanes

give the pleasure of a sense of eternal recurrence.

Long ago I left behind

the visiting of cathedrals and fortified towers.

I am like someone who just sees and doesn't pass away,

a lofty spirit despite his gray head and the afflictions

of age.

Saved by his amazement, eternal and divine.

Genoa, 30 June 1999

Cho 88th Birthday của GCC

Thành phố đậm đặc với những lồi đi có mái che

dành cho khách bộ hành

Những quảng trường nhỏ hẹp, những vòm cung.

Những terraces dẫn xuống bãi biển

Và Gấu bị mê hoặc bởi cái vẻ đẹp

của 1 thân thể trẻ trung, không thể kéo dài

Cái duyên dáng nhảy múa của nó

giữa những viên đá cổ xưa

Màu áo dài mùa hè

Tiếng guốc rộn ràng giữa những hè phố hàng

hàng thế kỷ của khu Phố Cổ

Chúng đem tới cái lạc thú của một cảm quan

về 1 quy hồi vĩnh cửu

Đã lâu lắm rồi

Gấu không còn có cái thú thăm

viếng thành quách, lâu đài, tháp cổ….

Gấu như 1 ai đó, chỉ nhìn, và đứng ỳ ra, đếch

chịu đi xa, lên chuyến tàu suốt!

Một thứ tinh anh, cái gì gì “nhân hậu

và cảm động”, như Seagull đã từng nhìn ra

Mặc dù chẳng còn cái răng nào, tóc

bạc phếch, và cái đau tuổi già

Được cứu vớt nhờ cái sự ngỡ ngàng, hoài

hoài, thiêng liêng, thần thánh

Hai bài sau đây, có thể gửi theo

TTT.

AGAINST THE POETRY OF PHILIP LARKIN

I learned to live with my despair,

And suddenly Philip Larkin's there,

Explaining why all life is hateful.

I don't see why I should be grateful.

It's hard enough to draw a breath

Without his hectoring about nothingness.

My dear Larkin, I understand

That death will not miss anyone.

But this is not a decent theme

For either an elegy or an ode.

My dear Larkin

Chết chẳng tha 1 ai

Nhưng đâu phải đề tài sạch sẽ

Cho 1 bi khúc, hay 1 ode!

ON THE DEATH OF A POET

The gates of grammar closed behind him.

Search for him now in the groves and wild forests of

the dictionary.

Cái cánh cổng văn phạm - rằng, sáng

mai "khua" thức, hay, "khuya" thức, đưa em vào "quán

trọ", hay, "quán rượu" - đã đóng lại sau lưng

ông.

Kiếm ông ta bây giờ, là ở trong rừng

thông Đà Lạt, hay, ở mùa này, gió

biển thổi điên lên lục địa!

Ars Poetica?

By Czeslaw Milosz

Translated by Czeslaw Milosz and Lillian

Vallee

I have always aspired to a more spacious form

that would be free from the claims of poetry or prose

and would let us understand each other without exposing

the author or reader to sublime agonies.

In the very essence of poetry there is something indecent:

a thing is brought forth which we didn’t know we had in us,

so we blink our eyes, as if a tiger had sprung out

and stood in the light, lashing his tail.

That’s why poetry is rightly said to be dictated by a daimonion,

though it’s an exaggeration to maintain that he must be an angel.

It’s hard to guess where that pride of poets comes from,

when so often they’re put to shame by the disclosure of their

frailty.

What reasonable man would like to be a city of demons,

who behave as if they were at home, speak in many tongues,

and who, not satisfied with stealing his lips or hand,

work at changing his destiny for their convenience?

It’s true that what is morbid is highly valued today,

and so you may think that I am only joking

or that I’ve devised just one more means

of praising Art with the help of irony.

There was a time when only wise books were read,

helping us to bear our pain and misery.

This, after all, is not quite the same

as leafing through a thousand works fresh from psychiatric clinics.

And yet the world is different from what it seems to be

and we are other than how we see ourselves in our ravings.

People therefore preserve silent integrity,

thus earning the respect of their relatives and neighbors.

The purpose of poetry is to remind us

how difficult it is to remain just one person,

for our house is open, there are no keys in the doors,

and invisible guests come in and out at will.

What I'm saying here is not, I agree, poetry,

as poems should be written rarely and reluctantly,

under unbearable duress and only with the hope

that good spirits, not evil ones, choose us for their instrument.

Berkeley, 1968

Ars Poetica?

Tôi luôn luôn thèm một thể thức rộng rãi

hơn

Nó sẽ rủ bỏ ba thứ đòi hỏi nhảm nhí của, thơ

hay văn xuôi, và

Nó sẽ làm cho chúng ta, người nọ hiểu người kia

hơn, mà

Không cần bày ra, hoặc xô đẩy, tác giả hay

người đọc

Tới những thống khổ siêu phàm

Ở trong cái yếu tính rất ư là yếu tính,

của thơ, có cái rất ư là thô bỉ, trơ trẽn,

đếch ra làm sao cả

1 điều chường ra đó, cái điều mà chúng

ta cũng không hề biết, nó có ở trong chúng ta

Và nó là chúng ta lòa con mắt

Như thể có 1 hổ từ đâu phóng ra

Và sừng sững trong ánh sáng, quật quật cái

đuôi.

Chính là do như thế mà thơ được coi như là

được quỉ phán, bảo, ra lệnh…

Tuy nhiên thật cường điệu khi coi thứ quỉ ma này phải

là 1 thiên thần

Thật khó mà biết được niềm kiêu hãnh của

những thi sĩ tới từ đâu

Bởi là vì thường xuyên lũ này áo

thụng vái nhau, bày ra nỗi tủi hổ là sự bạc nhược

của chúng.

Điều mà 1 con người biết điều mong muốn, sẽ là một thành

phố của quỉ

Chúng xử sự như thể chúng đang ở nhà, nói

nhiều thứ tiếng, và

Không hài lòng vì chôm chĩa, môi

hoặc tay

Bèn làm cái việc là, thay đổi số phận

của chúng, coi số phận là tiện lợi?

Rõ ràng là, vào lúc này,

thật ghê tởm khi… ghê tởm được đánh giá

cao

Và như thế, có thể là bạn nghĩ, tôi đang

nói đùa, nói rỡn chơi,

Hay tôi phịa ra thêm 1 phương tiện

Hay ca ngợi Nghệ Thuật với sự trợ giúp của tiếu lâm,

khôi hài

Đó là 1 thời mà chỉ những sách minh triết

được viết ra

Giúp chúng ta chịu đựng được nỗi đau và sự khốn

cùng

Điều này, nói cho cùng, thì là

như nhau

Như lật lật cả ngàn tác phẩm mới tinh, từ những bịnh

viện tinh thần, tức nhà thương điên

Dù thế nào, thế giới khác hẳn, điều xem ra nó

có thể

Và chúng ta thì khác, chúng ta

nhìn chúng ta, theo kiểu gầm rú, hò hét

Con người từ đó, bèn chọn sự nguyên vẹn thầm lặng

Nhờ vậy được bà con lối xóm kính nể

Mục đích của thơ ca là để nhắc nhở chúng ta

Thật khó khăn luôn luôn, mãi mãi,

chỉ là 1 người

Bởi là vì nhà của chúng ta mở rộng cửa,

không có khóa

Và những người khách vô hình ra vô

thoải mái

Điều mà tôi muốn nói ở đây, thì không

phải, tôi đồng ý, thơ

Như những bài thơ nên được viết, hiếm hoi đi, họa hoằn

thêm ra, ngần ngại mãi ra

Dưới cái sự cứng rắn không thể nào chịu nổi

Và chỉ với hy vọng

Rằng

Chính là những tinh anh, tính khí tốt,

“nhân hậu và cảm động”… chúng chọn chúng ta,

chứ không phải lũ quỉ ma, bộ lạc Cờ Lăng, hay Bắc Bộ Phủ chọn chúng

ta

Như là những dụng cụ của chúng.

Everness

Mai sau dù có

bao giờ

Một điều, mình

nó không thôi, thì không

hiện hữu - Sự Lãng Quên

Ông Trời, Người kíu kim

loại, kíu kít kim loại – còn gọi là

gỉ sét -

Và trữ, chứa trong hồi ức tiên

tri của Xừ Luỷ,

Những con trăng sẽ tới

Những con trăng những đêm nào

đã qua đi

Mọi thứ thì, rằng thì

là, cứ thế bày ra đó

Ngàn ngàn những phản chiếu

Giữa rạng đông và hoàng

hôn

Trong rất nhiều tấm gương

Là khuôn mặt Em để lại

[Cái gì gì, đập

cổ kính ra tìm lại bóng]

Hay, sẽ để lại, trước khi soi bóng

Và mọi điều thì là

phần của cái hồi nhớ tản mạn, long lanh, vũ trụ;

Làm gì có tận cùng

cho những hành lang khẩn cấp của nó

Những cánh cửa đóng lại

sau khi Em đi

Chỉ ở mãi phía xa kia,

trong rực rỡ dương quang

Sẽ chỉ cho Em thấy, sau cùng,

những Nguyên Mẫu và những Huy Hoàng

Everness

One thing

does not exist: Oblivion.

God saves the metal and he saves the

dross,

And his prophetic memory guards from

loss

The moons to come, and those of evenings

gone.

Everything is: the shadows

in the glass

Which, in between the day’s two twilights,

you

Have scattered by the thousands, or

shall strew

Henceforward in the mirrors that you

pass.

And everything is part of that diverse

Crystalline memory, the universe;

Whoever through its endless mazes wanders

Hears door on door click shut behind

his stride,

And only from the sunset’s farther side

Shall view at last the Archetypes and

the Splendors.

http://tuvala.blogspot.ca/2012/04/jorge-luis-borges-everness.html

Khi chôm Nguyễn