|

http://www.nybooks.com/…/michael-ondaatje-warlight-mists-o…/ The Mists of Time

Hermione Lee Warlight

by Michael Ondaatje. Knopf, 290 pp., $26.95 The narrator of Warlight, an Englishman called Nathaniel Williams who is fourteen when the story begins and twenty-nine (though sounding much older) when he looks back and tries to piece it all together, tells himself this about the past: You return to that earlier time armed with the present, and no matter how dark that world was, you do not leave it unlit. You take your adult self with you. It is not to be a reliving, but a re-witnessing. Dark worlds, blackouts, night scenes,

bonfires in unlit streets, the hour before dawn "as night began dissolving,"

sodium lamps, points of light, writing by candlelight, and the gray

buildings of postwar London pattern this novel of chiaroscuro. Secrets

and hidden lives remain obscure for a long time; some mysteries never

come to light; some things stay lost in darkness. The narrator is feeling

his way back through the half-dark. The readers are no wiser than the

characters. We're in the "unlit." too. There are clues everywhere from

the first page, tiny details waiting to have their meaning detonated

much later on-a sprig of rosemary placed in a pocket, a line from a Schumann

song, a squeaking floorboard, a scribbled map-but we have to piece them

together, as the narrator does, like a jigsaw puzzle or papers in an

archive. We share the narrator's hesitancy and uncertainty, and we have

to be patient. In The Cat's Table, we're told, with approval, about

a filmmaker who doesn't want his audience to feel wiser than his characters:

"We do not have more knowledge than the characters have about themselves."

The effect of that method here is slow, suspenseful, and disquieting. "In 1945 our parents went away and left us in the care

of two men who may have been criminals," Warlight begins, with

irresistible laconic oddness. The parents say they are going to Singapore

for a year, for the father's job. The mother, Rose, makes much of packing

her trunk. Nathaniel and his older sister Rachel ("Stitch" and "Wren,"

as their mother calls them) are left in the house in Ruvigny Gardens in

South London, in the care of a hesitant, inscrutable, music-loving person

called Walter, whom they nickname The Moth. He fills their parents' house

with floating visitors, all with a variety of specialized, sometimes dubious,

professions. Ondaatje loves crafts and skills-from bridge-building to bomb

disposal-and by the end of the novel we, and Nathaniel, will have learned

a great deal about greyhound racing (and smuggling), meteorology, roof

climbing, making flies for fishing, thatching, beekeeping, wildfowl shooting,

barge steering, chess moves, and the making of maps. **** Rachel's theatrical world mirrors the theater of the

novel. Everyone is on- stage; everyone is camouflaged or has a false name.

Ruvigny Gardens feels to Nathaniel "like an amateur theatre company."

No one is what he or she seems. Like secretive poker players, they are

all breasting their cards, as The Darter teaches Nathaniel to do. Gradually,

through the secrets and disguises, the story of their mother, Rose, begins

to emerge out of her camouflage. It turns out to be her book as much

as her son's, and he becomes the indirect narrator of her life. ***** Realizing, years later, how unknowing, ignorant-or innocent-he

was, Nathaniel has to ask himself how dangerous he was to others, how

much damage he did unknowingly. His strange rite of passage from childhood

to adulthood has to be rethought. He ends up looking back at damage and

tragedy from the apparent safety of his "walled garden" in Suffolk, a

regretful, sad narrator, like Dowell in Ford Madox Ford's The Good Soldier,

or Tony Webster in Julian Barnes's The Sense of an

Ending, or Maurice Bendrix in Graham Greene's The End of the Affair.

Sometimes we travelled east beyond

Woolwich and Barking, and even in the darkness knew our location by just

the sound of the river or the pull of the tide. Beyond Barking there was

Caspian Wharf, Erith Reach, the Tilbury Cut, Lower

Hope Reach, Blyth Sands, the Isle of Grain, the estuary,

and then the sea. As in Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness or Charles

Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, this river too is one of the dark

places of the earth. Warlight (which is full of literary, musical,

and theatrical allusions) is partly an adventure story of danger and discovery.

The boy sometimes feels he is in a fairy tale, or an old ballad, or a

detective novel, or a thriller. But as his angry, alienated sister will

tell him, their story is not a childhood romance: "We were damaged, Nathaniel.

Recognize that." She reminds him of the Schumann song that their guardian,

The Moth, used to play to them, with the line: "Mein Herz ist schwer,"

Heavy, difficult: that is the reality of life. Note: Trên đây là bài điểm

cuốn Warlight trên NYRB. Tin Văn post, và hy vọng

dịch ra tiếng Việt, sau. Whose story is this? Có thể nói, nó cùng 1 dòng

với Lần Cuối Sài Gòn của GCC, nhưng, khác, vì

là truyện dài, tiểu thuyết! Mi trở lại quá khứ, trang bị bằng hiện tại, và dù quá khứ có tối thui cỡ nào, khi từ giã nó, mi không hề muốn nó tối thui như thế nữa. Mi mang cái “thằng tôi bây giờ của mi” cùng với mi, và như thế, không phải "sống lại", mà là "chứng thực lại" Ui chao, GCC đã từng viết, đúng như thế, về Sài Gòn: Trong mỗi chúng ta đều có 1 Sài Gòn âm ỉ cháy, tôi đốt lên ngọn nến của tôi, để cho Sài Gòn của bạn sáng ngời!

May 31st 2018 Warlight. By Michael Ondaatje. Knopf; 304 pages; $26.95. Jonathan Cape; £16.99. A CHARACTER in “Warlight”, Michael Ondaatje’s seventh novel, remarks that “Wars don’t end. They never remain in the past.” Not in England, anyway, where the mythology of the second world war has shaped and distorted the nation’s identity. A quarter-century ago, the Sri Lankan-born Canadian writer won global acclaim with “The English Patient”. With subtlety and grace, that novel clouded the legends of conflict in Egypt and Italy in doubts as dense as a Western Desert sandstorm. Now Mr Ondaatje, who spent his teenage years in London, returns to Britain’s war and its immediate aftermath. “Warlight” unfolds after 1945 in a bomb-ravaged city that, although victorious, “still felt wounded, unsure of itself”. Nathaniel, the narrator, is a junior British intelligence officer. From the vantage-point of the late 1950s, he looks back to Blitz-wrecked London and seeks to understand the “omissions and silences” that haunted his disrupted childhood. His father, an executive with Unilever, apparently left for a post in Singapore. Rose, his beloved but elusive mother, also vanished—to work undercover, the reader grasps by increments, in the “unknown and unspoken world” of the secret services. Already shaped by this “family of disguises”, Nathaniel and his rebellious sister Rachel grow up in the care of louche informal guardians who make a murky living “on the edge of the law”. Known by nicknames such as “the Moth” and “the Pimlico Darter”, these memorable hustlers move their “shifting tents of spivery” through the hotels and bombsites of London in a time of “fewer rules, less order”. Nathaniel, and Mr Ondaatje, relish these underworld adventures. A fledgling spy, Nathaniel learns to be “a caterpillar changing colour” to survive. Meanwhile the novel glances at the chaos of post-war Europe, where Rose operates in the shadows. Score-settling between armed factions, notably in Yugoslavia, persists despite Germany’s surrender, as “acts of war continued beyond public hearing”. Yet an “almost apocalyptic censorship”, which British intelligence abets, hides this (largely forgotten) bloodshed. There is, Nathaniel reflects, “so much left unburied at the end of a war”. Mr Ondaatje illuminates this rubble-strewn landscape from angled sidelights. Lyrical but oblique, his prose matches a mood of mystery and suspicion that tantalises, if occasionally frustrates, the reader. With Nathaniel, he shows the child observer as a kind of secret agent, piecing together baffling fragments picked up from the hidden lives of adults. As more of Rose’s career in espionage becomes visible, along with the clandestine stunts of the Moth and his pals, “Warlight” also explores the English talent for camouflage and deceit: “the most remarkable theatrical performance of any European nation”. Still, those arts of subterfuge that win a war may ruin the peace. A colleague of Rose’s in the twilit fellowship of spies reads a classified report about the state of continental Europe, which finds that “nothing has moved into the past and no wounds have healed with time”. That verdict, “Warlight” suggests, applies on the British side of the Channel. This article appeared in the Books and arts section of the print edition under the headline "In the shadows of war" Tks. NQT Một nhân vật trong cuốn tiểu thuyết thứ bẩy của Michael Ondaatje, “Warlight”, phán, “Chiến tranh không chấm dứt. Chúng chẳng bao giờ ngủ yên trong quá khứ”. Không ở Anh, tuy nhiên, nơi huyền thoại học về cuộc đệ nhị thế chiến đã vẽ nên, và vặn vẹo, cái gọi là căn cước quốc gia. Một phần tư thế kỷ trước đây, nhà văn Canada gốc Sri Lanka được cả thế giới ngưỡng mộ với cuốn Bệnh Nhân Anh. Với sự tinh tế, và ân sủng, cuốn tiểu thuyết – như những đám mây - phủ lên lên những huyền thoại về cuộc tranh chấp, xung đột ở Ai Cập, và ở Ý, trong những hồ nghi, đậm đặc như những trận bão cát ở Sa Mạc Tây Phương. Bây giờ, Mr Ondaatje, người đã từng trải qua thời niên thiếu ở Luân Đôn, trở lại với cuộc chiến Anh và những năm hậu chiến tức thời liền sau đó Warlight mở ra sau 1945 trong1 thành phố bị bom cày nát bấy, mà, mặc dù thắng trận, “vẫn cảm thấy đau nhức vì những vết thương, và không chắc chắn về chính nó”. Nathaniel, người kể chuyện là sĩ quan tình báo Anh, loại tép riu, junior. http://www.tanvien.net/tgtp_02/michael_ondaatje.html

Ðề từ And this is how I see the East

.... I see it always from a small boat-not a light, not a stir, not a sound.

We conversed in low whispers, as if afraid to wake up the land .... It is

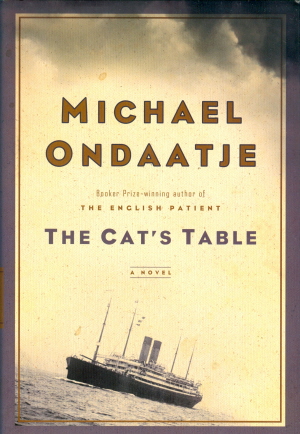

all in that moment when I opened my young eyes on it. Lời giới thiệu trang bìa Tiểu sử MICHAEL ONDAATJE is the author of novels, a memoir, a non-fiction book on film, and eleven books of poetry. His novel 'The 'English 'Patient won the Booker Prize; another of his novels, Anil's Ghost, won the Irish Times International Fiction Prize, The Giller Prize, and the Prix Médicis[của Tây].

FICTION The Cat's Table by Michael Ondaatje (Cape,

hardback, out August 21st).

Michael Ondaatje: The divided man Novelist and poet Michael Ondaatje,

who won the Booker prize for The English Patient, draws on his own extraordinary

life to conjure up evocative tales of duality and displacement. Robert McCrum

asks how much reality there is in his fiction…

Double vision: a Canadian citizen,

Michael Ondaatje is still “profoundly Sri Lankan”. Photograph: Jeff Nolte

Một ngày của nhà văn thì nó ra làm sao? Michael Ondjaatje: Rất đơn điệu, bạn sẽ rất thất vọng! Tôi viết buổi sáng, chiều bò ra đường, gặp bạn, chẳng có chi là đặc biệt hết. Tôi có 1 tương quan thể lực, un rapport physique, với Canada, và đặc biệt là với thành phố Toronto, nơi tôi sống kể từ 1964. Đông phương, 1 cái gì ảo, un imaginaire, đối với ông? Sau Bệnh nhân Anh, tôi trở về Sri Lanka, tạo những mối liên hệ, rằng buộc, thu thập tài liệu viết Le Fantôme d’Avril, Bóng Ma Tháng Tư, thấm đậm hơn nhiều, xa hơn nhiều, so với 1 Sri Lanka hiện thực và di động. Hơn tất cả, tôi coi mình là 1 người dân Canada. Đó là những cội rễ mới. Là Ca na điên, là thế nào? Làm sao ông định nghĩa nó? Đúng là 1 câu hỏi đặc Tẩy. Đó là 1 xứ sở của những di dân, di trú, một xứ mở, un pays d’ouverture. Những người Âu Châu đã biến nó thành thuộc địa, rồi những người di dân từ khắp nơi tới, Jamaiques, Tẫu, Sri Lanka… Tôi không thể sống trong 1 khí hậu chính trị như ở Mẽo, tôi… thua! Tôi thích có 1 khoảng cách, một quãng xa, sự lặng lẽ gần như của 1 tỉnh lỵ địa phương, ce calme presque provincial, của Canada, và tôi có thể nhập vào sự bình an, thiên nhiên, ở đó thật đơn giản biết bao. Note: Cuốn mới ra lò của ông này,

được khen tới chỉ. Thấy ở tiệm sách, bản bìa cứng, có

chữ ký của tác giả, giá bốn bó, đau dế quá,

đành vờ. Bài trên Guardian

http://www.tanvien.net/Viet/A_Place_In_The_Country.html

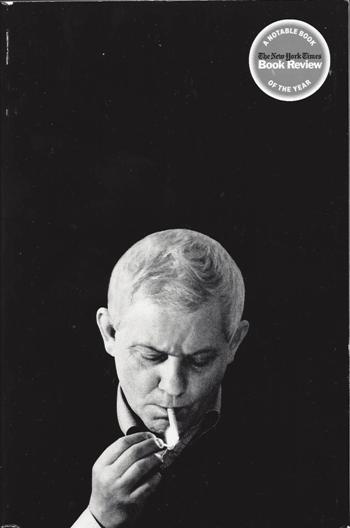

The Genius of Robert Walser http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2000/nov/02/the-genius-of-robert-walser/ J.M. Coetzee November 2, 2000 Issue Was Walser a great writer? If one is reluctant to call him great, said Canetti, that is only because nothing could be more alien to him than greatness. In a late poem Walser wrote: I would wish it on no one to be me. Only I am capable of bearing myself. To know so much, to have seen so much, and To say nothing, just about nothing. Walser, nhà văn nhớn? Nếu có người nào đó, gọi ông ta là nhà văn nhớn, 1 cách ngần ngại, thì đó là vì cái từ “nhớn” rất ư là xa lạ với Walser, như Canetti viết. Như trong 1 bài thơ muộn của mình, Walser viết: Tớ đếch muốn thằng chó nào như tớ, hoặc nhớ đến tớ, hoặc lèm bèm về tớ, hoặc mong muốn là tớ Nhất là khi thằng khốn đó ngồi bên ly cà phê! Một mình tớ, chỉ độc nhất tớ, chịu khốn khổ vì tớ là đủ rồi Biết thật nhiều, nhòm đủ thứ, và Đếch nói gì, về bất cứ cái gì [Dịch hơi bị THNM. Nhưng quái làm sao, lại nhớ tới lời chúc SN/GCC của K!] Walser được hiểu như là 1 cái link thiếu, giữa Kleist và Kafka. “Tuy nhiên,” Susan Sontag viết, “Vào lúc Walser viết, thì đúng là Kafka [như được hậu thế hiểu], qua lăng kính của Walser. Musil, 1 đấng ái mộ khác giữa những người đương thời của Walser, lần đầu đọc Kafka, phán, ông này thuổng Walser [một trường hợp đặc dị của Walser]." Walser được ái mộ sớm sủa bởi những đấng cự phách như là Musil, Hesse, Zweig. Benjamin, và Kafka; đúng ra, Walser, trong đời của mình, được biết nhiều hơn, so với Kafka, hay Benjamin. W. G. Sebald, in his essay “Le Promeneur Solitaire,” offers the following biographical information concerning the Swiss writer Robert Walser: “Nowhere was he able to settle, never did he acquire the least thing by way of possessions. He had neither a house, nor any fixed abode, nor a single piece of furniture, and as far as clothes are concerned, at most one good suit and one less so…. He did not, I believe, even own the books that he had written.” Sebald goes on to ask, “How is one to understand an author who was so beset by shadows … who created humorous sketches from pure despair, who almost always wrote the same thing and yet never repeated himself, whose prose has the tendency to dissolve upon reading, so that only a few hours later one can barely remember the ephemeral figures, events and things of which it spoke.”

Bài viết của Coetzee về Walser, sau đưa vô “Inner Workings, essays 2000-2005”, Gấu đọc rồi, mà chẳng nhớ gì, ấy thế lại còn lầm ông với Kazin, tay này cũng bảnh lắm. Từ từ làm thịt cả hai, hà hà! Trong cuốn “Moral Agents”, 8 nhà văn Mẽo tạo nên cái gọi là văn hóa Mẽo, Edward Mendelson gọi Lionel Trilling là nhà hiền giả (sage), Alfred Kazin, kẻ bên lề (outsider), W.H, Auden, người hàng xóm (neighbor)… Bài của Coetzee về Walser, GCC mới đọc lại, không có tính essay nhiều, chỉ kể rông rài về đời Walser, nhưng mở ra bằng cái cảnh Walser trốn ra khỏi nhà thương, nằm chết trên hè đường, thật thê lương: On Christmas Day, 1956, the police of the town of Herisau in eastern Switzerland were called out: children had stumbled upon the body of a man, frozen to death, in a snowy field. Arriving at the scene, the police took photographs and had the body removed. The dead man was easily identified: Robert Walser, aged seventy-eight, missing from a local mental hospital. In his earlier years Walser had won something of a reputation, in Switzerland and even in Germany, as a writer. Some of his books were still in print; there had even been a biography of him published. During a quarter of a century in mental institutions, however, his own writing had dried up. Long country walks—like the one on which he had died—had been his main recreation. The police photographs showed an old man in overcoat and boots lying sprawled in the snow, his eyes open, his jaw slack. These photographs have been widely (and shamelessly) reproduced in the critical literature on Walser that has burgeoned since the 1960s Walser’s so-called madness, his lonely death, and the posthumously discovered cache of his secret writings were the pillars on which a legend of Walser as a scandalously neglected genius was erected. Even the sudden interest in Walser became part of the scandal. “I ask myself,” wrote the novelist Elias Canetti in 1973, “whether, among those who build their leisurely, secure, dead regular academic life on that of a writer who had lived in misery and despair, there is one who is ashamed of himself.”

|