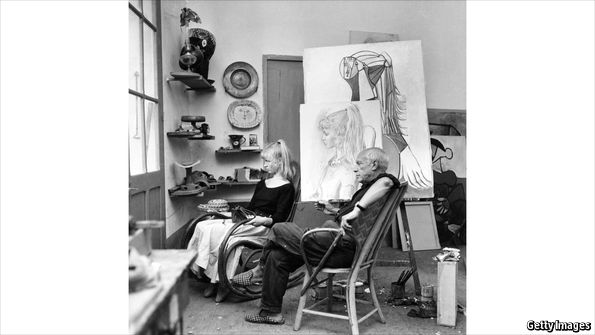

FRANÇOISE GILOT, Picasso's long-term partner, compared the artist to Bluebeard, the fictional nobleman who murdered a string of wives. Both Picasso's mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter and his second wife Jacqueline Roque committed suicide. But one woman who was subject to Picasso's gaze refused to fall victim to it.

Sylvette David began her artistic career not as a painter, but as a model. Picasso and she met in the spring of 1954 in Vaullauris. Whilst Sylvette sat in the sun outside his studio, Picasso scaled the wall to hand her a sketch of a girl with a ponytail, which she recognised to be a portrait of herself. From that point, Ms David became his muse for over fifty paintings, later known as the Sylvette Cycle. The “Heads of Sylvette”—a series of metal sculptures—constituted an important innovation in his career, and this new epoch in Picasso's art was also his most concentrated body of work centred around one woman. LIFE magazine dubbed it his “Ponytail Period”.

At the time, it was a tumultuous period for Picasso's personal life: Gilot, mother of his two children, had ended their relationship. Alone and vulnerable, he found comfort in Sylvette's innocence. “He was devastated when Francoise left. I helped heal his unhappiness,” she recalls. Indeed, the time spent together appears to have been an elixir for both artist and subject: “As a child I was abused by one of my mother's boyfriends. I didn't like men to look at me. Picasso was the first man to really see me...it gave me strength and confidence in myself.” She hints that Picasso sensed the deeper reason for her timidity, which lead to the portrait of her without a mouth and the statue of her with a key.

In following years, art historians have tended to snub the Sylvette series on the grounds that it does not qualify as serious art: Sylvette and Picasso's relationship remained purely platonic, and the series came to a halt when Picasso began a relationship with Roque. As a result, the Sylvette Cycle is often dismissed as nothing more than a superficial interval. Some critics feel it focuses too much on fugacious details—Sylvette's ponytail or her distinctive coat with large buttons—and lacks Picasso's characteristic depth and insight. But as Christoph Grunenber, the director of the Kunsthalle Bremen in Germany, puts it, “Maybe it was her resistance to be seduced by him that made him need to see her: because he didn't conquer her, he needed to conquer her on canvas and on paper and in sculpture.”

Having been object of both the dominant male gaze of Picasso and the dismissive gaze of the art-world, the famous muse has since wrested control back into her hands and is now an artist in her own right. She has changed her name to Lydia Corbett and is currently exhibiting at the prestigious Fosse Gallery, with an autobiography published by Unicorn Press set for release later this year. Once too uncomfortable to pose in the nude for Picasso, she has since inverted the roles of artist and muse and now uses her experience with him as inspiration.

Ms Corbett's paintings in both oil and watercolour have gathered worldwide acclaim: she has exhibited at the Tate and counts the Anthony Petullo Foundation among her clients. With its freedom of form, fluid lines and bright colours, her distinctive style possesses a childlike quality. Like Picasso, she plays with scale and perspective, and interweaves human subjects with the surreal. In among the dreamlike images her narrative is clear to see—except this time, she retells her story in her own words.

Sylvette and Lydia. By Lydia Corbett and Isabel

Coulton. To be published by Unicorn in October; 256 pages; £30