|

"Tôi chẳng

là cái quái gì Fernando

Pessoa "Đám

đông độc giả" có lẽ chỉ biết tới tên nhà thơ Fernando Pessoa, lần đầu

tiên, qua Saramago. Khi được giải Nobel văn chương (1998), ông cho

biết, đây là

tác giả ruột của mình. Nhưng phải đợi tới khi Cao Hành Kiện vinh danh

nhà thơ

người Bồ đào nha, trong bài diễn văn nhận giải Nobel văn chương (2000),

"Lí do của văn học", "nhà thơ thâm trầm nhất của thế kỉ 20 là

Fernando Pessoa", thiên hạ mới tá hỏa! Tá hoả, đúng

như vậy, không chỉ với Đông phương mà luôn cả Tây phương, nhất là cõi

văn viết

bằng tiếng Anh. Eugénio Lisboa, một trong hai người biên tập cuốn

"Fernando Pessoa: A Centenary Edition" (nhà xb Carcanet, Manchester)

ghi nhận: khi Harold Bloom cho xuất bản cuốn "Cõi Văn Tây" (tạm dịch

từ "The Western Canon", 1949), và để Pessoa vào trong danh sách 26

tác giả hàng đầu, một tay điểm sách trên tờ Time, (vì lịch sự, W.S. Mervin, tác

giả bài viết về Pessoa, "Dấu chân của một cái bóng", trên tờ Điểm

Sách New York, số đề ngày 3.12.1998, đã không nêu tên), đã "bực

mình"

cho rằng, vị giáo sư đáng nể này chiều theo sự yếu đuối riêng tư, khi

tự cho

mình có cặp mắt tinh đời, nhận ra được những tác giả hũ nút mang tính

hàn lâm. Hôm nay, tôi sáng suốt, như thể tôi sắp lìa đời"      “Cuốn sách của

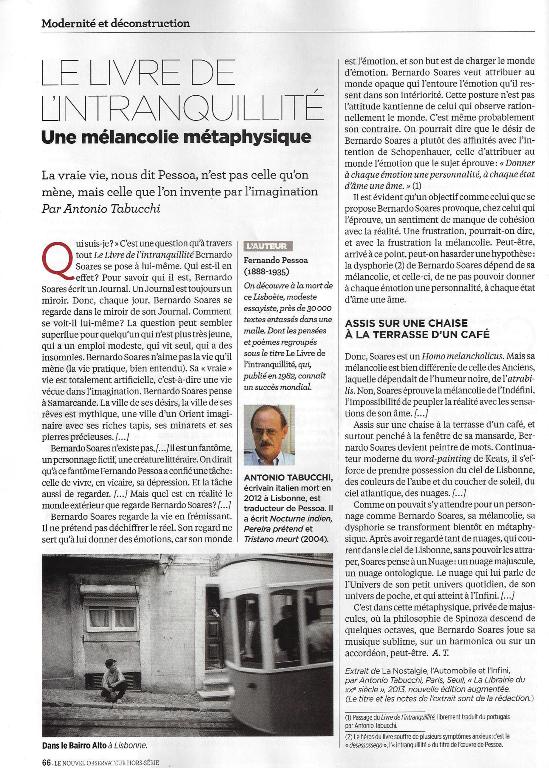

sự đếch làm sao mà trầm lắng được”: Nỗi buồn siêu hình Đời thực,

Pessoa biểu chúng ta, không phải cuộc đời mỗi đứa còng lưng ra mà cõng,

nhưng

mà là cuộc đời mỗi “Anh Cu Gấu” phịa ra, nhờ tưởng tượng! Il faut savoir voir Lisbonne

pendant le temps exact d'un sanglot. La voir tout entière, par exemple,

dans la première lumière du matin. Ou la voir complètement dans le

dernier reflet du soleil sur la Rua da Prata. Puis pleurer. Parce que,

même si c'est la première fois qu'on la voir, on a l'impression d'y

avoir déjà vécu toutes sortes d'amours tronquées, d'illusions perdues

et de suicides exemplaires. le quartier littéraire de

Lisbonne Ôi chao giá như viết nổi như

dòng như trên đây. Về Sài Gòn Góc văn của

Sài Gòn, như của Lisbonne, là Quán Chùa. Sống ở

Lisbonne như thể nó là một cây diêm lạnh giá, trong khi những căn nhà

của những

con người yêu thương nó run rẩy qua những dòng nước mắt. Fernando

Pessoa's multiple voices have different styles and idioms, and each one

is

extraordinary. George Steiner raves about The Book of Disquiet George

Steiner The

Observer, Sunday 3 June 2001 Was 18 March

1914 the most extraordinary date in modern literature? On that day,

Fernando

Antonio Nogueira Pessoa (1888-1935) took a sheet of paper, went to a

tall chest

of drawers in his room and began to write standing up, as he

customarily did.

'I wrote 30-odd poems in a kind of trance whose nature I cannot define.

It was

the triumphant day of my life, and it would be impossible to experience

such a

one again.' Other poets,

notably Rilke, have experienced such hours of explosive prodigality.

But

Pessoa's case is different and, probably, unique. The first set of

poems was by

one 'Alberto Caeiro' - 'my Master had appeared inside me.' The next six

were

composed by Pessoa struggling against the 'inexistence' of Caeiro. But

Caeiro

had disciples, one of whom, 'Ricardo Reis', contributed further poems.

A fourth

individual 'burst impetuously on the scene. In one fell swoop, at the

typewriter, without hesitation or correction, there appeared the "Ode

Triumphal" by "Alvaro de Campos" - the Ode of that name and the

man with the name he now has.' Pseudonymous

writing is not rare in literature or philosophy (Kierkegaard provides a

celebrated instance). 'Heteronyms', as Pessoa called and defined them,

are

something different and exceedingly strange. For each of his 'voices',

Pessoa

conceived a highly distinctive poetic idiom and technique, a complex

biography,

a context of literary influence and polemics and, most arrestingly of

all,

subtle interrelations and reciprocities of awareness. Octavio Paz

defines

Caeiro as 'everything that Pessoa is not and more'. He is a man magnificently at home in nature, a virtuoso of pre-Christian innocence, almost a Portuguese teacher of Zen. Reis is a stoic Horatian, a pagan believer in fate, a player with classical myths less original than Caeiro, but more representative of modern symbolism. De Campos emerges as a Whitmanesque futurist, a dreamer in drunkenness, the Dionysian singer of what is oceanic and windswept in Lisbon. None of this triad resembles the metaphysical solitude, the sense of being an occultist medium which characterise Pessoa's 'own' intimate verse. Other masks followed, notably one 'Bernardo Soares'. At some complex generative level, Pessoa's genius as a polyglot underlies, is mirrored by, his self-dispersal into diverse and contrasting personae. He spent nine of his childhood years in Durban. His first writings were in English with a South African tincture. He turned to Portuguese only in 1910 (there are significant analogies with Borges). Pessoa

earned his living as a translator. His legacy, enormous and in large

part

unpublished, comports philosophy, literary criticism, linguistic

theory,

writings on politics in Portuguese, English and French. Like Borges,

Beckett or

Nabokov, Pessoa shows up the naive, malignant falsehood still current

in

certain Fenland English faculties whereby only the monoglot and native

speaker

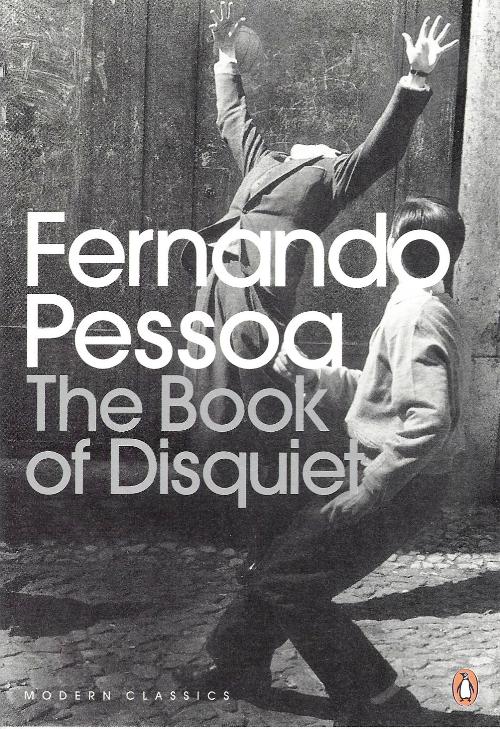

is inward with style and literary insight. The fragmentary, the incomplete is of the essence of Pessoa's spirit. The very kaleidoscope of voices within him, the breadth of his culture, the catholicity of his ironic sympathies - wonderfully echoed in Saramago's great novel about Ricardo Reis - inhibited the monumentalities, the self-satisfaction of completion. Hence the vast torso of Pessoa's Faust on which he laboured much of his life. Hence the fragmentary condition of The Book of Disquiet which contains material that predates 1913 and which Pessoa left open-ended at his death. As Adorno famously said, the finished work is, in our times and climate of anguish, a lie. It was to

Bernardo Soares that Pessoa ascribed his Book of Disquiet, first made

available

in English in a briefer version by Richard Zenith in 1991. The

translation is

at once penetrating and delicately observant of Pessoa's astute

melancholy.

What is this Livro do Desassossego ? Neither 'commonplace book', nor

'sketchbook', nor 'florilegium' will do. Imagine a fusion of

Coleridge's

notebooks and marginalia, of Valery's philosophic diary and of Robert

Musil's

voluminous journal. Yet even such a hybrid does not correspond to the

singularity of Pessoa's chronicle. Nor do we know what parts thereof,

if any,

he ever intended for publication in some revised format. What we have

is a haunting mosaic of dreams, psychological notations,

autobiographical

vignettes, shards of literary theory and criticism and maxims. 'A

Letter not to

Post', an 'Aesthetics of Indifference', 'A Factless Autobiography' and

manual

of welcomed failure (only a writer wholly innocent of success and

public

acclaim invites serious examination). If there is

a common thread, it is that of unsparing introspection. Over and over,

Pessoa

asks of himself and of the living mirrors which he has created, 'Who am

I?',

'What makes me write?', 'To whom shall I turn?' The metaphysical

sharpness, the

wealth of self-scrutiny are, in modern literature, matched only by

Valery or

Musil or, in a register often uncannily similar, by Wittgenstein.

'Solitude

devastates me; company oppresses me. The presence of another person

derails my

thoughts; I dream of the other's presence with a strange

absent-mindedness that

no amount of my analytical scrutiny can define.' This very scrutiny,

moreover,

is fraught with danger: 'To understand, I destroyed myself. To

understand is to

forget about loving.' These findings arise out of a uniquely spectral

yet

memorable landscape: 'A firefly flashes forward at regular intervals.

Around me

the dark countryside is a huge lack of sound that almost smells

pleasant.' Throughout,

Pessoa is aware of the price he pays for his heteronomity. 'To create,

I've

destroyed myself... I'm the empty stage where various actors act out

various

plays.' He compares his soul to 'a secret orchestra' (shades of

Baudelaire)

whose instruments strum and bang inside him: 'I only know myself as the

symphony.' At moments, suicidal despair, a 'self-nihilism', are close.

'Anything, even tedium', a finely ironising reservation, rather than

'this

bluish, forlorn indefiniteness of everything!' Is there any city which

cultivates

sadness more lovingly than does Lisbon? Even the stars only 'feign

light'. Yet there are also epiphanies and passages of deep humour. In the 'forests of estrangements', Pessoa comes upon resplendent Oriental cities. Women are a chosen source of dreams but 'Don't ever touch them'. There are snapshots of clerical routine, of the vacant business of bureaucracy worthy of Melville's Bartleby. The sense of the comedy of the inanimate is acute: 'Over the pyjamas of my abandoned sleep...' The juxtapositions have a startling resonance: 'I'm suffering from a headache and the universe.' A sort of critical, self-mocking surrealism surfaces: 'To have touched the feet of Christ is no excuse for mistakes in punctuation.' Or that fragment of a sentence which may come close to encapsulating Pessoa's unique reckoning: '... intelligence, an errant fiction of the surface'. This is not

a book to be read quickly or, necessarily, in sequence. Wherever you

dip, there

are 'rich hours' and teasing depths. But it will, indeed, be a banner

year if

any writer, translator or publisher brings to the reader a more

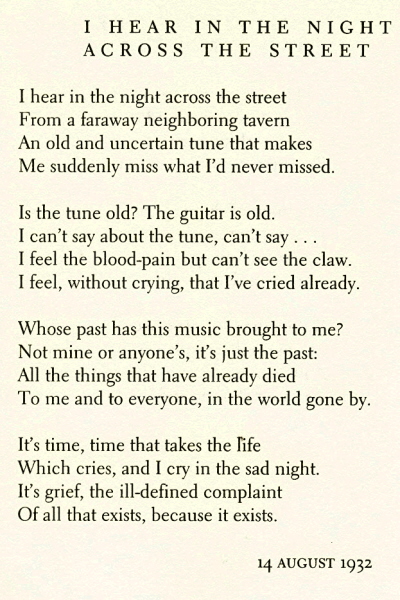

generous gift.  Fernando Pessoa Note: Bài thơ trên TV đã

dịch, nhưng không làm sao kiếm ra. Đành dịch một lần nữa vậy, vì bất

ngờ, GCC nhớ ra cái điệu nhạc trên là của một bài nhạc sến. Gấu nghe trong đêm,

chạy dài theo con phố Gấu

nghe trong đêm, Điệu

nhạc xưa? Cái đàn ghi ta cũ. Quá

khứ nào điệu nhạc mang lại cho Gấu? Tới giờ rồi. Giờ nghỉ chơi

với cuộc đời

Nó khóc, và Gấu khóc, trong đêm buồn Đó là nỗi sầu đau, là lời thở than mập mờ, không làm sao định nghĩa được Về mọi điều hiện hữu, bởi vì nó hiện hữu (1) (1) Khổ thơ chót, GCC dịch

trật: Chính là thời gian, cái

thời gian đã lấy đi đời sống, (Nói một cách hơi cải

lương rằng thì là - nhưng không bảo đảm đúng- : Tks. Many Tks Đời sống đã mất, nỗi đau

vẫn còn. Đúng như thế.

|