Old

I Fang Confession Tinvan in Zcheh Terrible Tiger Suu-Kyi homecoming Higgs boson Dalai Lama News Rosler Philip Crime by France in France Nobel 2012 Baby-Lift Thống Kê TinVan Booker 2013 O Du Kích Nhỏ SV/VNCH/chống Tàu Phù Sài Gòn mưa lụt HCM vs TH Runner Runner Putin Pique Ukraine vs Thầy Kuốc Lễ Hội của Cái Vô Nghĩa Sài Gòn Mưa Đầu Mùa Piketty-Eco-Superstar Hồn ma Thiên An Môn Wall Street ngợi ca Phở Chúc mừng bạn Hàm Summer & World Cup 2914 Huỳnh Tấn Mẽn Đoan Trang Văn Học Đô Thị Miền Nam KL vs VC Xi-Jinping Trường hợp Võ Phiến Hongkong Protest Nobel 2014 The Wall Torture Văn Học Ngụy vs VH/VC Orwell World Camus vs Meursault-Phản điều ta 2015 Man Booker Viet_Obs Mùa Mưa 2015 Saigon Nobel văn chương 2015 RFA by Lu_Giang Migration & Asylum Trong_Lu_by the_Economist Sóng hấp dẫn Valentine's Day 2016 Canada Britain Muslim Opinion Man Booker 2016 Obama in VN Biển Đông Nổi Sóng Nobel văn chương 2010 Lịch sử suy tư của Mít Biển Đông Người Kinh Tế Ultimate Barbarity Lái xe ở VN 2-ethics-tales Nobel Peace 2016 Nobel văn chương 2016 Man Booker 2016 USA Best Hope New US Affairs Secretary Archive 3 2 1 Nổi dậy ở Nhà Trắng Roth vs Trump Đồng Tâm problem Nobel Văn Chương 2017 |

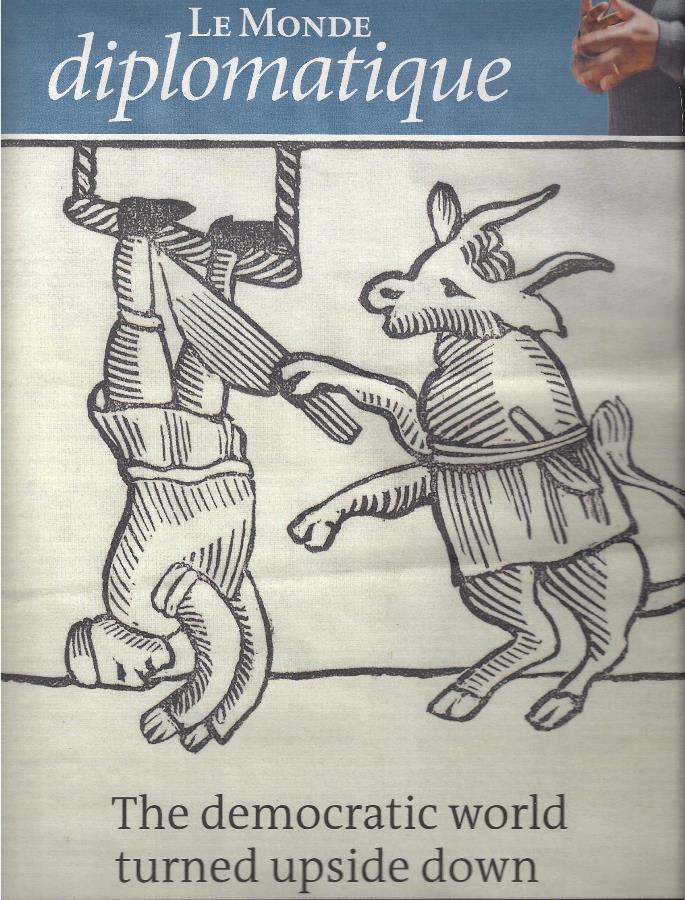

Nếu Tờ Răm [Trump, đọc theo kiểu thủ tướng Fuck của Vẹm], có thể là Tông Tông Mẽo, chuyện gì cũng có thể xẩy ra. Thế Giới Ngoại Giao Tẩy, le Monde Diplomatique, Dec 2016 "Xì

tai hoang tưởng" [paronoid style] của chính trị Mẽo.

Dolnad Trump đã thành công, trong cái trò ma nớp [manipulating] những xốn xang [anxieties] của Yankees mũi lõ. Những niềm tin riêng của ông ta, và tương lai chính trị, đếch biết được! http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/02/13/trumps-radical-anti-americanism http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/02/06/trumps-information-wars Báo chí, câm miệng lại. Đã có cái loa phường rồi!

Trump và cái loa phường http://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment Nếu cái loa phường ở xứ Bắc Kít có chân, thì nó cũng hạ cánh an toàn ở xứ Mẽo! “Welcome to your destiny.” In the next four to eight years, the U.S. will be commandeered by a relentless deluge of misinformation. Trong 4 hoặc 8 năm tới, xứ sở của Yankee Mũi Lõ sẽ bị điều khiển, chỉ huy... bởi trận lũ lụt của thứ thông tin dởm, sai, lệch, giả, ngụy tạo... In the next four to eight years,

American children will be born in a country led by a vainglorious man who

wishes to subordinate facts to his ego.

*** If you were a child growing up in China in the late nineteen-eighties, you learned fairly early the universe of things that were less than dependable: hot water, the bus schedule, and, most irritatingly—if you were an introverted second grader—the capricious offerings of the itinerant book cart. But one aspect of our lives, from birth until, it seemed to me, death, remained as constant as the sunrise. This was the voice of the loudspeaker broadcasts in our Army hospital compound (my mother was a military doctor), which woke me every morning before I could witness the dawn, accompanying me through all three meals and, as I brushed my teeth for bed, sometimes long after dusk. The first time I read “1984,” George Orwell’s classic dystopia, I was an eleventh grader in America, and its portrayal of a world rife with loudspeaker announcements and an omnipotent Party did not strike me as related to the world we had left behind when I was eight years old. Winston Smith, the protagonist of “1984,” is confined in an authoritarian prison, deprived of the most fundamental freedoms and inculcated with Newspeak. In my early childhood, at least as I remembered it, everyone I knew lived ordinary, unmolested lives. An impassioned teacher, given to rhetorical drama, once tried to convince me otherwise: “Don’t you see? The Chinese government hurt its own people, and you were a helpless victim.” But I’m not hurt, I insisted. “I mean, a victim of that cruel society,” she pleaded, in the manner of a missionary, impatient with the pagan who won’t see the light. The two of us went on like this for some time, both growing increasingly exasperated, neither capable of explaining to the other her version of truth and reality. Other details in our conversation have been lost to time, but I never shook the expression on her face, flushed grapefruit pink and, it seemed to me, quivering on the precipice of tears. Years later, I recognized the expression on my teacher’s face as one of profound frustration with perceived irrationality. I knew it because, when I tried to begin a conversation with my mother about the inglorious deeds of the Chinese Communist Party (of which she had been a dedicated member for two decades), she recoiled with such violence that I understood instantly that my catalogue of facts was irrelevant. A complete rejection of the Party would amount to a denial of the better part of her adult life. It was not political but personal, and rationality had nothing to do with it. Rational reasoning and truth have been much on my mind as we enter a world of alternative facts and crypto-fascist edicts from the White House, less than two weeks into Donald Trump’s Administration. Last week, when “1984” rose toward the top of Amazon’s best-seller list, I dug out my dog-eared paperback copy and reread a quotation that I had underlined a decade and a half earlier: “For, after all, how do we know that two and two make four? Or that the force of gravity works? Or that the past is unchangeable? If both the past and the external world exist only in the mind, and if the mind itself is controllable—what then?” In recent days, as Trump and his cohorts have peddled blatant falsehoods—that his Inauguration attracted the largest crowd in history, or that he lost the popular vote owing to millions of votes by illegal aliens—I have wondered about the extent to which minds can be controlled, or, rather, commandeered, by the relentless deluge of misinformation. Like many Chinese immigrants, my mother and I came to America so that my father could pursue graduate studies, not to seek political freedom. When I was old enough to study the Cultural Revolution and the Tiananmen massacre, periods in Chinese history when the authoritarian government subjected its citizenry to inexpressible brutality, I would wonder about everything I knew, or thought I had known. The one time I asked my mother about why she did not resist, she answered distractedly and somewhat defensively: it was a very confused time. Who could know what was true and what was false? What to believe and whom to trust? The muddling of fact and fiction is a tried-and-true tactic of totalitarian regimes. What’s more, when the two are confused for long enough, or when an indefatigable war on truth has been waged for a year, or two years, or perhaps eight, it will likely be harder and more tiresome to untangle them and remember a time when a firm line was drawn between the true and the false as a matter of course. If amnesia breeds normalization, fatigue has always served as the authoritarian’s great accomplice. At the time my mother and I were getting ready to leave for America, neither of us knew the ways in which the contours of the world could be different. For people of my mother’s generation, the Party’s truth had become so embedded in their understanding of themselves that the boundary between what they represented and what the government propagandized had faded, shifting to form the outline of a manufactured reality. Perhaps this is exactly what Trump and his more ideological aides, Steve Bannon among them, envision. But it’s just as likely that they, too, have become so convinced of their alternative reality that what we recognize to be fiction genuinely constitutes their fact. Orwell again: “If you want to keep a secret, you must also hide it from yourself.” In any case, no matter what Trump thinks of China, something about the increasingly aggressive repression of the media by China’s President, Xi Jinping, may well hold some appeal for him as a model. How liberating would it be, Trump might wonder, to make all legislation a matter of executive orders and sign them at will without Congress, vexing million-strong protests, and a media that readily reports them? In the next four to eight years, American children will be born in a country led by a vainglorious man who wishes to fit facts—and their future—into the convenient shape of his ego. But democracy, freedom of expression, and, above all, the right to truth are not antiquated pieties. They belong to citizens who can still make their voices heard, before resignation metastasizes into complacency, exhaustion into self-doubt. The struggle will be to maintain openness and tolerance as the norm, the values that our children absorb into their identities naturally—to be defended rather than be defensive about. On the day that Donald Trump was inaugurated, I received a message from a man who had previously disparaged my work on social media: “Welcome to your destiny.” I imagined him smirking as he typed those words and I wanted to tell him that he got it backward, that I already know what it is like to live in a world with an omnipotent leader and a renovated reality. I have known loudspeakers, their mass persuasions, emotional arousals, and booming, relentless broadcasts. And I know that they are not my destiny, because I won’t let them be. By Jiayang Fan Note: Bài viết này, TV sẽ có bản tiếng Việt. Còn mấy bài trên Người Kinh Tế về Trump, có post lại trong mục Thời Sự, cũng đáng đọc. Thêm bài nóng hổi, nổi dậy ở Nhà Trắng! Cứ như VC cướp chính quyền ở Hà Lội 1945!

Thời sự http://www.economist.com/blogs/democracyinamerica/2017/01/fantasy-justice If humankind couldn’t predict Mr Trump, perhaps it can predict what Mr Trump will do Predicting

Donald Trump’s pick for the Supreme Court

PREDICTION, wrote Karl Popper, a philosopher, is “one of the oldest dreams of mankind—the dream of prophecy, the idea that we can know what the future has in store for us, and that we can profit from such knowledge by adjusting our policy to it.” It is a dream from which Donald Trump provided a shock awakening. Over the summer of 2015, as Mr Trump surged in primary polls, analysts and journalists laid out, often in precise and gory detail, the steep trajectory of his inevitable fall. “Why the Republican Party shouldn’t worry about the Donald” and “Donald Trump’s Six Stages Of Doom” are representative headlines from those months. A year later, in an arena in Cleveland, Mr Trump accepted his party’s nomination. But he didn’t stand a chance in the general, according to the people for whom predicting these sorts of things is their business. On the morning of November 8th, the Huffington Post gave Hillary Clinton a 98% chance of being elected president. The Princeton Election Consortium gave her a 93% chance. The New York Times arrived at 85%, and FiveThirtyEight, a data journalism website (where your blogger is employed part-time), at a more tempered 71%. But at 3am the next day, in a Hilton ballroom in Midtown Manhattan, Mr Trump delivered his victory speech. This bloody face-plant into the cold cement of unpredictability will do little to deter future prognosticative efforts, however. Indeed, they’re already well underway. If humankind couldn’t predict Mr Trump, perhaps it can predict what Mr Trump will do. For instance: What does the future of the Supreme Court hold? The court has been shorthanded since the death of Justice Antonin Scalia last February. Congressional Republicans successfully ignored Barack Obama’s nominee, Merrick Garland, for ten months, leaving Mr Trump with a powerful political card to play. What will he draw out of the deck? There have been some official hints already. In May, Mr Trump released a list of 11 potential nominees to the court, assembled with the assistance of the conservative Heritage Foundation. In September, he augmented it with 10 more. In early January, those 21 were whittled down to a shortlist of eight, according to Politico. But one project is gazing more deeply at the judicial tea leaves. FantasyJustice is a crowd-sourced prediction market of sorts, offering a menu of potential Trump justices, on which visitors to its website can vote. It’s an offshoot of FantasySCOTUS—fantasy sports but for predicting Supreme Court opinions. (For the most recent full term, its experts boasted an 84% accuracy rate.) Thousands have weighed in, and three favourite contenders for the vacant seat have emerged. http://www.newyorker.com/news/john-cassidy/donald-trumps-new-world-disorder His trade approach to China could lead to a crash in the global financial markets. And that would be just the beginning In

1990, after the Berlin Wall came down, one of Trump’s Republican predecessors,

George H. W. Bush, talked about establishing a “New

World Order,” in which all the world’s nations could “prosper and

live in harmony.” That turned out to be largely wishful thinking. But,

for more than twenty-five years, the United States continued to pursue

the postwar vision of an open global trading system, which developing

countries such as China and India could choose to participate in—as they

eventually did. Trump’s “America First” vision is very different. It is

parochial, overtly nationalist, and focussed on obtaining immediate benefits

for his alienated supporters. If he isn’t careful, it could turn out to

be a recipe for a New World Disorder.

From private emperor to public envoyDonald Trump chooses Rex Tillerson as secretary of state

“A DIPLOMAT that happens to be able to drill oil.” That is how Reince Priebus, Donald Trump’s incoming chief of staff, described Rex Tillerson, the boss of ExxonMobil, who was nominated this week as America’s secretary of state. In fact, Mr Tillerson, 64, is an oil driller through and through, has spent 41 years furthering the ambitions of one of the world’s largest private companies, and has often sidelined the American government because he felt ExxonMobil was better able to look after its global affairs itself. Yet he has a reputation for dependability and small-town Texan values that has enabled him to stand up to, and win respect from, notoriously slippery world leaders such as Vladimir Putin. The question is, will it help him become a good envoy-in-chief for diplomacy’s nemesis, Mr Trump? Or will he also peddle Mr Trump’s “I win, you lose” sense of international relations, with oil interests always in the back of his mind? For a leader of the world’s corporate elite, Mr Tillerson has parochial roots. Born in Wichita Falls, Texas, he grew up as a Boy Scout, went to the University of Texas, and rides horses in a cowboy hat in his spare time. He has worked at ExxonMobil since 1975, never lived outside America, and speaks with a drawl. Jack Randall, a friend from university days and an oil banker at Jefferies, recounts how Mr Tillerson still spends time after work fixing up the decking on his lakeside home, despite having numerous employees who would do it for him. “He’s a regular guy who has lived the American dream,” he says. “He’s a Texan, an engineer and a Boy Scout. That is where his values come from.” Yet as an oilman and ExxonMobil’s chief executive since 2006, Mr Tillerson has run operations in some of the most inhospitable parts of the world, from ice-encrusted Sakhalin in the Russian Far East, to poverty-stricken Chad. That has meant dealing with populist strongmen, from Mr Putin to Venezuela’s late leader Hugo Chávez, who he has often cajoled into submission by arguing for the importance of free markets and the sanctity of oil contracts. In a book on ExxonMobil, “Private Empire”, author Steve Coll recounts Mr Tillerson’s early dealings with Mr Putin during efforts to rein in an unruly Russian partner, Rosneft, on the Sakhalin development. When Mr Putin offered to write an executive order pushing ahead with the project, Mr Tillerson refused, saying that the Russian president lacked the legal authority to live up to his company’s standards. Though Mr Putin “blew his stack,” he gave in to Mr Tillerson’s demands. In a later oil era, in 2011, ExxonMobil and Rosneft struck a deal to develop oil in Russia’s Kara Sea, which Mr Putin said could lead to a whopping $500 billion of Arctic co-developments. In 2013 Mr Putin awarded Mr Tillerson Russia’s Order of Friendship. The Arctic deal was scuppered because of American sanctions against Russia, following its annexation of Crimea in 2014, which were opposed by Mr Tillerson. James Henderson, an expert on Russian oil at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, says the Kremlin came to respect ExxonMobil under Mr Tillerson, despite the firm’s stubborn belief in its own value system, because it was “dependable”. He says: “Exxon always makes the point very clearly that it all has to be above board. Its terms do not involve brown envelopes under the desk.” Mr Tillerson’s ties to Mr Putin are likely to complicate his confirmation hearings, especially amid allegations that Russian hackers interfered with America’s presidential election to help Mr Trump. But his defenders are adamant about his integrity. “The chances are better that Mother Teresa was stealing money from her charity than Rex Tillerson will do anything with Putin that isn’t in the best interests of the United States,” Mr Randall says. What is less clear is how he will deal with America’s traditional allies, such as Europe, who fear Russian meddling in Ukraine, for example. His appointment will rekindle suspicions that American diplomacy is about securing oil and other scarce resources. NGOs allege that ExxonMobil has a poor record of promoting human rights in countries where it operates, and has flip-flopped on climate change. Yet as well as having an oilman’s resource-hungry mindset, he could also bring useful industry traits to the State Department—and to a Trump presidency. For example, finding and drilling oil requires elaborate modelling—both of underground geologies and messy above-ground geopolitics—to make money over the long-term. He knows that such models are as likely to be wrong as well as right. Reputedly his engineering background makes him a stickler for evidence-based decision-making. He is also considered “patient and unemotional” on ExxonMobil’s side of the negotiating table. Such traits would make him very different from Mr Trump, who lives by the gut. “Rex is not a guy who wets his finger and puts it up in the air to see which way the wind is blowing, and he’ll tell Mr Trump what he thinks,” Mr Randall says. In some respects his opinions differ from Mr Trump's, too. Though once a climate-change denier, he now believes mankind has helped cause global warming. Last year ExxonMobil supported the Paris agreement on climate change. In the past he has strongly rebuffed calls (recently supported by Mr Trump) to make America energy independent. With luck, he will not only have the tactical skills to further America’s interests abroad. He will also have the integrity to talk sense into his boss |