Nguyễn Quốc Trụ

Sinh 16 tháng Tám,

1937

Kinh

Môn,

Hải

Dương

[Bắc

Việt]

Quê

Sơn

Tây

[Bắc

Việt]

Vào

Nam

1954

Học

Nguyễn

Trãi

[Hà-nội]

Chu Văn An,

Văn Khoa

[Sài-gòn]

Trước

1975

công

chức

Bưu

Điện

[Sài-gòn]

Tái

định

cư năm

1994

Canada

Đã

xuất

bản

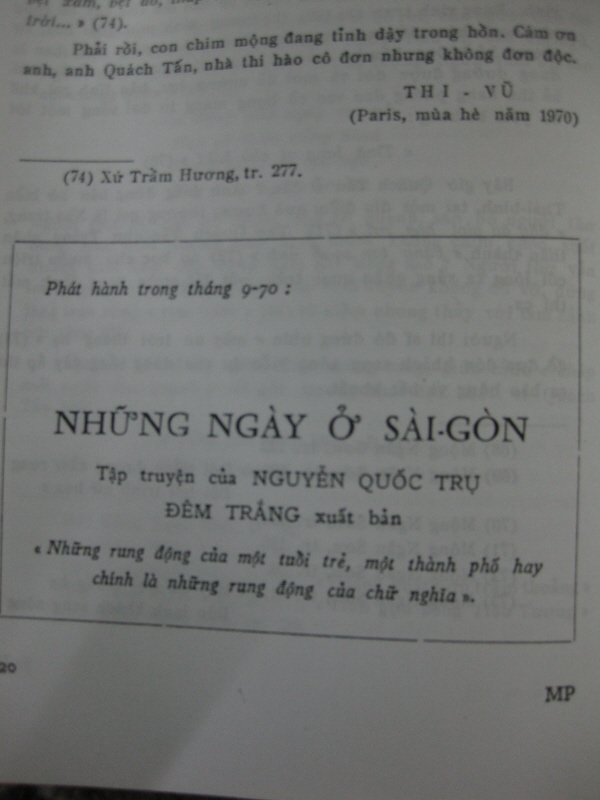

Những

ngày

ở Sài-gòn

Tập

Truyện

[1970,

Sài

Gòn,

nhà

xb Đêm

Trắng

Huỳnh

Phan

Anh

chủ

trương]

Lần

cuối,

Sài-gòn

Thơ,

Truyện,

Tạp

luận

[Văn

Mới,

Cali.

1998]

Nơi

Người

Chết

Mỉm Cười

Tạp

Ghi

[Văn

Mới,

1999]

Nơi

dòng

sông

chảy

về phiá

Nam

[Sài

Gòn

Nhỏ,

Cali,

2004]

Viết

chung

với

Thảo

Trần

Chân

Dung

Văn Học

[Văn

Mới,

2005]

Trang Tin Văn, front page, khi quá đầy,

được

chuyển

qua Nhật

Ký

Tin Văn,

và

chuyển

về

những

bài

viết

liên

quan.

*

Một

khi

kiếm,

không

thấy trên

Nhật

Ký,

index:

Kiếm

theo

trang

có

đánh

số.

Theo

bài

viết.

Theo

từng

mục,

ở đầu trang

Tin

Văn.

Email

Nhìn

lại

những

trang

Tin

Văn

cũ

1

2

3

4

5

Bản quyền Tin Văn

*

Tất

cả bài

vở

trên

Tin Văn,

ngoại

trừ

những

bài

có

tính

giới

thiệu,

chỉ

để sử dụng

cho cá

nhân

[for personal

use], xài

thoải

mái

[free]

Liu

Xiaobo

Elegies

Nobel

văn

chương

2012

Anh

Môn

Kỷ niệm 100 năm sinh của Milosz

IN MEMORIAM

W. G. SEBALD

http://tapchivanhoc.org

|

Happy New Year

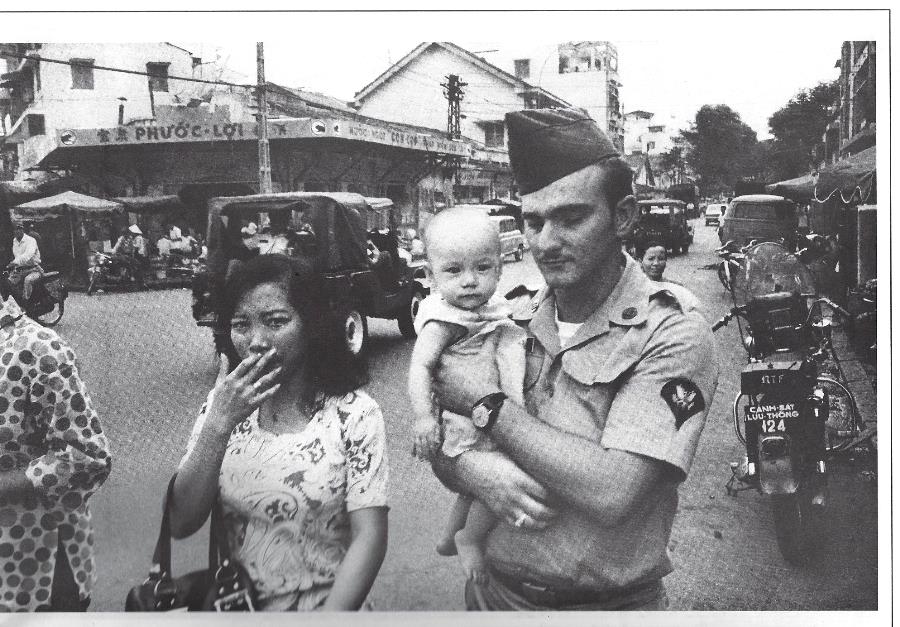

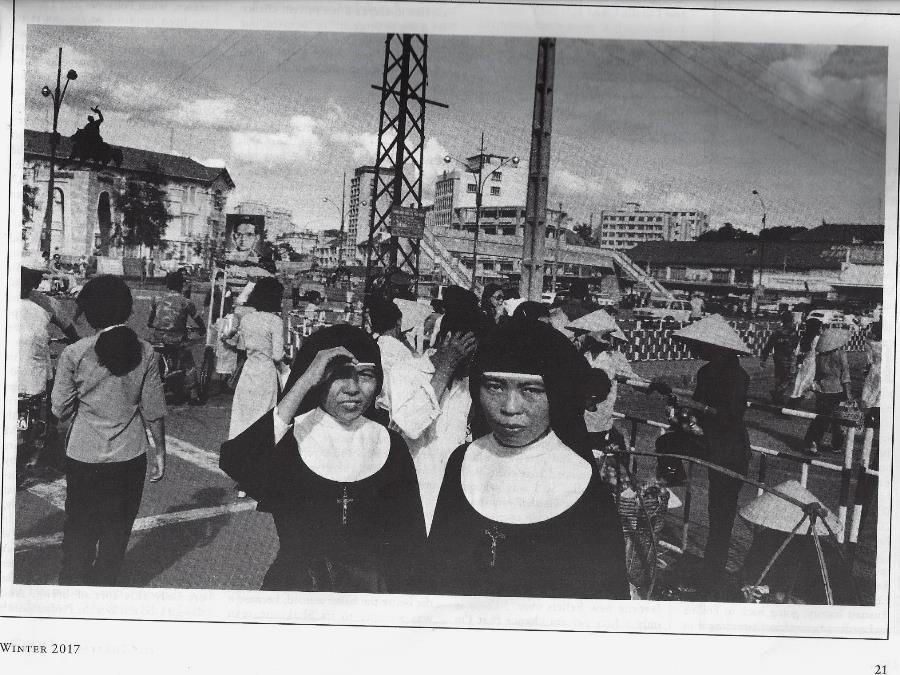

Noel 1968,

Mậu Thân, @ Thương Xá TAX

31.12.2016

Mưa Sài Gòn, hình

chụp góc Lê Lợi và Công Lý, ngày

12 tháng 6 năm 1968.

Happy New Year

Nhà mà không

có cái ghế bành thật thoải mái, và một

người ngồi đến nhẵn thín, thì căn nhà đó đếch

làm sao có được một linh hồn.

A house that does not have one worn, comfy chair in it is soulless.

Mary Sarton, 1973

Đọc thì bèn nhớ đến

NXH

Tớ nghĩ là Camus chỉ ra rằng,

có thể ngồi trong cái ghế bành của NXH, và

sống 1 cuộc đời phiêu lưu lớn đến tận Tiểu Sài Gòn,

đến San Jose, rồi mất ở đó!

I think it was Camus who pointed out that it is possible to lead a

life of great adventure without leaving your desk

Geoff Dyer: Working the Room,

trong bài viết Ryszard Kapuscinki: African Life

Nhớ là Hemingway có

phán, thì về nhà để treo cái nón.

Ui choa, thèm về nhà – thì tất

nhiên, ở Saigon- chỉ để treo cái nón!

Bài của Dyer về Kạp, thần

sầu. Cũng ngắn thôi. Sẽ đi liền.

Theo Dyer có thể phát cho Kap hai Nobel, 1 văn chương,

1 hoà bường

http://www.tanvien.net/TG_TP/Milosz_Kap_To_Hoai.html

[Ở xứ Bắc Kít, thì

cảm thấy ra làm sao]

Thú thực,

cái nhìn như bây giờ của Gấu với những Tô Hoài,

Kap, là mới có đây thôi, sau khi bị 1 em Bắc

Kít mắng, khi viết về Kap.

Lúc đó, Gấu chưa đọc Kap, và cái bài

trên TV về ông, là tóm tắt 1 bài viết

trên TLS, khi ông mất.

Tờ TLS không ưa Kap, và còn không ưa nhiều

người nữa, trong có Linda Lê, thí dụ.

Chỉ 1 khi bị em Bắc Kít “mắng”, Gấu mới tìm đọc Kap,

cùng lúc, nhìn lại Tô Hoài. Cái

bài đầu tiên Gấu đọc Kap, là 1 truyện ngắn, [ký

thì đúng hơn], đăng trên 1 số Granta. Đọc, rồi

nhớ lại những năm chiến tranh, khi còn nhỏ, ở miền quê Bắc Kít,

và thế là bổi hổi bồi hồi, nhận ra… Gấu, anh cu Gấu, Bắc Kít,

nhà quê, trước khi được về Hà Nội học!

Hà, hà!

Ryszard Kapuscinski

Granta, Winter 2004

Số Granta về Mẹ, có bài viết

của Ryszard Kapuscinski, When there

is talk of 1945 [Nói về năm 1945 khi nào nhỉ?], thật

là tuyệt, với Mít, vì 1945 đúng là

cái năm khốn khổ khốn nạn của nó.

Ðây là 1 hồi

ức về tuổi thơ của ông, lần đầu nghe bom nổ, đâu biết bom là

gì, chạy đi coi, bị mẹ giữ lại, ôm chặt vào lòng,

và thì thào, cũng một điều đứa bé không

làm sao hiểu nổi: “Chết ở đó đó, con ơi, There’s

death over there, child”.

Những năm tháng chiến

tranh trùng hợp với ấu thời, và rồi, với những năm đầu của

tuổi trưởng thành, của tư duy thuần lý, của ý thức.

Thành thử với ông, chiến tranh, không phải hòa

bình, mới là lẽ tự nhiên ở đời, the natural state. Và

khi mà bom ngưng nổ, súng ngưng bắn, khi tất cả im lặng, ông

sững sờ. Ông nghĩ những nguời lớn tuổi, khi đụng đầu với cái

im lặng đó, thì bèn nói, địa ngục chấm dứt, hòa

bình trở lại. Nhưng tôi không làm sao nhớ lại

được hòa bình. Tôi quá trẻ khi đó. Vào

lúc chiến tranh chấm dứt, tôi chỉ biết địa ngục.

Một trong những nhà

văn của thời của ông, Boleslaw Micinski, viết, về những năm đó:

Chiến tranh không chỉ làm méo mó linh hồn, the

soul, của những kẻ xâm lăng, mà còn tẩm độc nó,

với thù hận, và do đó, chiến tranh còn làm

biến dạng những linh hồn của những kẻ cố gắng chống lại những kẻ xâm

lăng”. Và rồi ông viết thêm: “Ðó là

lý do tại sao tôi thù chủ nghĩa toàn trị, bởi

vì nó dạy tôi thù hận”.

Trong suốt cuộc chiến, hình

như Bắc Kít chưa từng quên hai chữ thù hận. Nhưng

hết cuộc chiến, vẫn không bao giờ quên cả. Thành thử,

cái còn lại muôn đời của cuộc chiến Mít, theo

GNV, chỉ là thù hận.

Một người như Kỳ Râu

Kẽm, “bó thân về với triều đình”, như thế, mà

đâu có yên thân. Chuyện ông bị đám

hải ngoại chửi thì còn có lý, vì rõ

là phản bội họ. Nhưng khốn nạn nhất là

lũ VC chiến thắng, chúng vẫn giở cái giọng khốn nạn ra, thôi

tha cho tên tội đồ. Cái “gì gì” đứa con hư đã

trở về nhà!

Tô Hoài by Nhật Tuấn

Note: Viết về Tô Hoài

như thế này thì sẽ không làm sao cắt nghĩa

được sự hiện hữu của những tuyệt tác của ông, nhất là,

“Ba Người Khác”.

Theo Gấu, đọc Tô Hoài, thì nên đọc song

song với những Milosz, Ryszard Kapuściński…

Đây là 1 đề tài

lớn của thế kỷ, và của Mít. Cả 1 nền văn học Miền Bắc, sau

chỉ còn lại, được, ở Nguyễn Tuân, Tô Hoài, và

1 phần nào, ở Nguyễn Khải.

Về Milosz, có thể đọc

mấy bài sau đây:

The wiles of

art

To wash

Đề tài này, mới

đây, Gấu được đọc cuốn của Todorov, mới cực thú: Hồi Ức như

Thuốc Chữa Cái Ác, Cái Quỉ Ma, Memory as a Remedy

for Evil. Ba Người Khác

là thứ hồi ức đó, cho/do chính Tô Hoài,

1 tên Đại Ác kể ra!

TV sẽ giới thiệu chương viết

về Cambodia và Khờ Me Đỏ.

How It Felt to Be There

Neal Ascherson

RYSZARD

KAPUSCINSKI: A LIFE

by Artur Domoslawski, translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones.

Verso, 456 pp., £25, September, 978 I 84467 858 7

There are two large question marks

over Kapuscinski. The first is about his writing. Did he make things up?

Did he manufacture quotes, say he had been to places when he hadn't, describe

scenes that never happened? If so, did he tell lies in his routine reporting,

as an agency man for the Polish Press Agency and Polish newspapers? Or did

he reserve for his famous books a style of 'literary reportage' in which

embroidery and even manipulation of the facts were skillfully used to create

a reality 'truer than the truth'? The second question mark is about his

politics: what he did and said when he was young, and how he covered it up

later. But here it's important to note a difference in the emphasis given

to those two question marks. For foreigners, especially Anglo-Saxon ones,

the real Kapuscinski problem is veracity. How should we read books like The

Emperor (based, according to him, on interviews with Haile Selassie's courtiers

after his empire had been overthrown) now that it seems unlikely that those

interviews took place as he described them?

Tờ Điểm Sách London, số 2 August,

2012 đọc tiểu sử của RYSZARD KAPUSCINSKI.

GCC bị tay này ám ảnh!

Và cứ nghĩ tới bạn của Gấu là Cao Bồi!

Có hai dấu hỏi to tổ bố về Kapuscinski: Thứ nhất là

về những gì ông viết. Không lẽ ông bịa, bịp?

Thứ nhì là về thái độ chính trị của ông

Du lịch cùng với Herodotus

Kapuscinski: A Life

RYSZARD KAPUSCINSKI’S colourful

writing, especially about Africa, gained him a global reputation in the

early 1980s. He became celebrated for his descriptions of Haile Selassie’s

tenebrous court in Ethiopia, the overthrow of the shah of Iran, and for

his knack of using vignettes of humble lives to tell big stories about poor

countries.

He was also slippery about his

own beliefs, careless with facts, a loyal servant of a totalitarian regime,

and cruel to those who loved him. That is the picture painted in Artur

Domoslawski’s compelling and controversial biography, published in Poland

in 2010 and now in English.

Mr Domoslawski is not a doctrinaire

anti-communist, for whom any collaboration with the regime is unforgivable

treachery. Nor is he one of those who prizes the beauty of Kapuscinski’s

prose over his professional lapses. Mr Domoslawski was a friend of the

great man; but resolved to treat his life as a subject for serious inquiry,

setting out with an open mind and detailed knowledge, and adding more insights

and evidence along the way.

The result is an exemplary explanation

of what made Kapuscinski tick. Growing up in Pinsk, in the (now lost)

eastern borderlands of pre-war Poland, he was caught between the hammer

and the anvil in the war years. The hungry little boy learned that the

brave die first. He saw neighbours tortured by the Nazis and others deported

by the Soviets. He later claimed (untruthfully) that his father had escaped

death at Katyn, where the Soviets killed more than 20,000 captured Polish

officers and reservists. But why did Kapuscinski, so insightful about others,

never give his own views on Stalin? Or on his decades as a communist-party

member? He joined as a youth and left only in 1981.

The experience of arbitrary

power and then political change at home did much to shape his understanding

of events abroad. His sympathy for victims of colonialism in Africa reflected

Poland’s captivity in the Soviet empire. His depiction of the absurdities

of the shah’s Iran was a clear critique of decaying Polish bureaucratic

socialism.

Freedom and the hard currency to travel

were rare privileges in the post-war decades. That meant loyalty. Kapuscinski

joined the Solidarity cause in 1980. But he was no dissident. Communism

was disappointing, but not diabolical. The system made mistakes, but they

were “our mistakes,” he argued.

Kapuscinski was not a typical

foreign correspondent: he went on his first trip, to India, speaking no

English. Unlike his glitzy Western counterparts, he travelled by bus and

lived in cheap hotels. Covering wars, he sometimes carried a gun, and used

it. He wrote regular confidential reports for the authorities and personally

briefed the party’s central committee. He sometimes sat on, or slanted,

stories vital to the communist cause, such as Cuban involvement in the

wars of southern Africa. He helped the Polish spy agency—not much, fans

say, and no worse, perhaps, than Western journalists did on their side.

But it all stains his reputation.

His personality is another puzzle.

A modest manner belied a detachment that shaded into arrogance. He was

a dreadful father. Absences and affairs tested sorely his wife’s loyalty.

Many who counted him as a friend found they remembered how he listened,

not what he confided.

A lack of self-confidence meant

that he longed to be liked and hated saying no. That helped him keep powerful

protectors who eased him through the thickets of Polish bureaucracy. It

also led him, oddly, to cut passages in the American edition of a book

that might have offended the CIA. He habitually sacrificed facts for effect.

He never corrected false assertions that he had “befriended” Che Guevara

and Patrice Lumumba. This hardly helped him in the unforgiving climate of

post-1989 Poland.

The translation by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

makes the sweep and tone of Mr Domoslawski’s Polish readable, without

sacrificing its curious, to English eyes, use of the present tense and

rhetorical questions. Readers feel sympathetic to the man, though bleakly

aware of his flaws. The playfulness of a gifted writer,

however delicious to read, can have victims. For the living, exaggerations

and inventions are hurtful, or worse, while the dead cannot complain. Having grown up in a system built on

lies, it is odd that Kapuscinski did not have more regard for the truth.

Lớn lên, trưởng thành,

trong 1 hệ thống được xây dựng bằng dối trá, lạ làm

sao là, K đếch thèm để ý đến chân ný!

Tuyệt!

Me-xừ

Nhật Tuấn không hiểu được điều này, nên cứ xỉ vả Tô

Hoài hoài!

Tô Hoài cũng có

thể phán như sau đây, về cái chuyện cứ đi nước ngoài

hoài!

Freedom and the hard currency to travel

were rare privileges in the post-war decades. That meant loyalty. Kapuscinski

joined the Solidarity cause in 1980. But he was no dissident. Communism

was disappointing, but not diabolical. The system made mistakes, but they

were “our mistakes,” he argued.

Tự do và đô la

Mẽo để đi dong chơi xứ người là những đặc quyền

những năm hậu chiến. Và nó có nghĩa là trung

thành. K gia nhập công đoàn Đoàn

Kết năm 1980. Nhưng ông đếch phải thứ ly khai. CS thì tởm, nhưng

chưa đến nỗi quỉ ma. Hệ thống có phạm lỗi lầm, đó là

“những lỗi lầm của chúng ta”, K vặc lại... Nhật Tuấn!

Sự khác biệt giữa Nhật

Tuấn, và Tô Hoài, là những tác phẩm.

Một giả, một thực. Với K & TH, đều là những tuyệt phẩm.

Chẳng có

chỗ cho cả hai, Brodsky và chủ nghĩa CS, trong cái xứ sở

thật rộng lớn đó. Bè lũ VC Nga bực bội với tất cả những gì

Brodsky làm, [cả đến chuyện đi ị, như nhà thơ NCT đã

từng bực, đúng vào ngày sinh nhật Bác]. Andrei Sergeev, bạn của Brodsky,

sau đó viết: Nhà chức trách không thể làm

bất cứ điều chi ngoài chuyện bực, với tất cả những gì Brodsky

làm, không làm, đi tản bộ loanh quanh, đứng, ngồi

ở bàn, nằm xuống giường, và ngủ. Brodsky vẫn cố tìm

đủ cách xb thơ của ông, vô ích. Tới mức, hai

ông cớm KGB gật đầu, chúng tao sẽ in thơ của mày, trên

loại giấy đặc biệt, bản quí, dành cho "bạn quí" của

mày, nếu mày đi một đường báo cáo về những

ông giáo sư, bạn của mi, chỉ là báo cáo

xuông, những chuyện làm xàm ba láp thôi.

The Gift

Thất Hiền

https://hoanghannom.com/2016/12/27/remordimiento-por-cualquier-muerte/

Hối tiếc về

bất kỳ cái chết

Chẳng có ký ức và hy vọng,

vô hạn, trừu tượng, gần như tương lai,

người chết chẳng phải một người nào chết: họ là cái

chết.

Như vị Chúa của các nhà thần bí,

Người mà họ phủ nhận mọi điều nói về Người,

người chết xa lạ ở mọi nơi

chẳng là gì ngoài sự diệt vong và thiếu

vắng của thế giới.

Chúng ta cướp khỏi họ mọi thứ,

chúng ta chẳng để lại một màu sắc hay một âm tiết:

đây là cái sân đôi mắt họ không

còn chia sẻ,

kia là vỉa hè nơi hy vọng họ lẩn khuất,

Ngay cả những gì chúng ta nghĩ

có thể họ cũng đang nghĩ;

chúng ta chia phần như những tên trộm

của cải của đêm và ngày.

Note: Đọc, "chẳng có ký

ức và hy vọng... ", là Gấu thấy có cái gì

kỳ kỳ rồi, và nhớ là bài thơ này Gấu đã

dịch rồi. Bèn gõ Bác Gúc, và bèn

coi lại luôn phần nguyên tác Tây Bán Nhà:

REMORDIMIENTO POR

CUALQUIER MUERTE

Libre de la memoria y de la esperanza,

ilimitado, abstracto, casi futuro,

e1 muerto no es un muerto: es la muerte.

Como el Dios de los místico,

de Quien deben negarse todos los predicados,

e1 muerto ubicuamente ajeno

no es sino la perdición y ausencia del mundo.

Todo se lo robamos,

no le dejamos ni un color ni una silaba:

aquí está el patio que ya no comparten sus ojos,

allí la acera donde acechó su esperanza.

Hasta lo que pensamos podría estarlo pensando él también;

nos hemos repartido como ladrones

el caudal de las noches y de los días.

http://www.tanvien.net/new_daily_poetry/3.html

Thời Tưởng Niệm

REMORSE FOR ANY DEATH

Free of memory and hope,

unlimited, abstract, almost future,

the dead body is not somebody: It is death.

Like the God of the mystics,

whom they insist has no attributes,

the dead person is no one everywhere,

is nothing but the loss and absence of the world.

We rob it of everything,

we do not leave it one color, one syllable:

Here is the yard which its eyes no longer take up,

there is the sidewalk where it waylaid its hope.

It might even be thinking

what we are thinking.

We have divided among us, like thieves,

the treasure of nights and days.

-W.S.M.

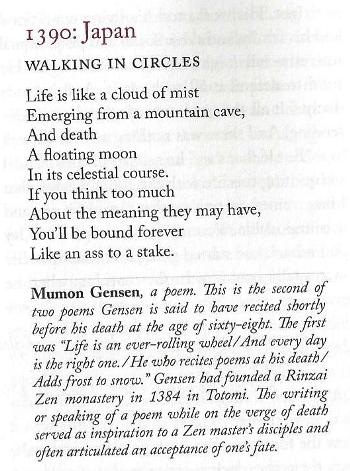

J.L. Borges

Ân hận vì bất cứ 1 cái chết

Thoát ra khỏi cả hồi ức

lẫn hy vọng

Không giới hạn, trừu tượng, xém 1 tí thì

là tương lai

Thi thể của ai đấy thì đếch phải là ai đấy: Nó

là cái chết.

Như Chúa Tể của những thần bí gia,

Kẻ đếch ai có thể thay thế, theo đám đệ tử này

năn nỉ,

Người chết đếch là ai cả, ở đâu đâu thì cũng

thế

Chẳng là cái chó gì hết, mà chỉ

là mất mát, vắng mặt, ra khỏi thế giới.

Chúng ta lột sạch tất cả, từ "nó": "cái gọi là

người chết đó"

Chúng ta chẳng để lại, một màu sắc, một âm, một

tiết, một… :

Đây là cái vườn mà những con mắt của nó

hết còn để mắt tới nữa

Đây là lối đi, nơi hy vọng của nó đã từng

đặt để

Nó chẳng từng đã từng suy tư, như chúng ta đang

suy tư?

Như những tên trộm,

Chúng ta chia sẻ, cấu xé, giành giựt,

Giữa chúng ta,

Kho tàng của những ngày

Và những đêm.

J.L. Borges

"Free of", libre de la .... làm sao lại dịch là "chẳng có"?

Chẳng cần nguyên tác, chẳng cần bản tiếng Anh, chỉ đọc

bản tiếng Mít không

thôi, là đã thấy nhảm rồi:

Chẳng

có ký ức!

NXH's Poems of the Night

Dịch thoáng:

Đời thì như "Mù Sương,

Sương Mù"

Thoát ra từ hầm núi

Và Chết,

Như “Người Đi Trên Mây”

Trên đường tới Thiên Đàng

Nhưng mà đừng suy tư nhiều quá về chúng

Nếu không muốn trở thành cù lần như GCC!

Portrait GCC

như vậy,

anh đi đã 2 năm. phùng nguyễn chụp tấm ảnh này

trong vườn nhà em, cũng theo anh đi, đã 1 năm.

2 Years Ago

See Your Memories

vậy là

hết nghe anh than: chán quá, anh chỉ muốn chết

giờ thì

anh đã chết và không còn gì để làm

anh chán nữa

nhớ lúc trước Quỳnh Như hay ‘quát’ anh: em đây

khô...

Bài thơ của Borges có trong Poems of the Night,

Gấu mua hình như cùng lúc với tập Thời Tưởng Niệm,

dịch lai rai, hy vọng bạn quí trong chuyến đi xa, có cái

để đọc.

Một vị độc giả vừa nhặt giùm 1 hạt sạt

from Seedtime

Let silent grief

at least

Hatch out that last chance

Of light.

Let that extremity

of wretchedness

Preserve the chance of flowers.

Translated .from

the French by Michael Hamburger

Ít nhất thì

hãy để nỗi đau thương âm thầm

Đóng sập cơ may cuối cùng của

Ánh sáng.

Hãy để tột

cùng bất hạnh

Gìn giữ cơ may của những bông hoa.

Tuyệt!

C. H. SISSON (1914-2003)

... "hatch

out" là tách ra, hé ra, nở ra chứ đâu có

"đánh sập" !! Thời gian giúp cho ánh sáng

có cơ may ngoi lên từ nỗi đau cũng như biết đâu chừng

có những đóa hoa ngoi lên từ sự khắc nghiệt .

HAPPY NEW YEAR TO

YOU AND YOUR FAMILY

Thơ

Mỗi

Ngày

For the Sleepwalkers

Đêm

đêm, như 1 tên mộng du, một mình mi tìm cách

trở về lại Saigon, trở lại Quán Chùa....

Tonight I want

to say something wonderful

for the sleepwalkers who have so much faith

in their legs, so much faith in the invisible

arrow carved into the carpet, the worn path

that leads to the stairs instead of the window,

the gaping doorway instead of the seamless mirror.

I love the way that sleepwalkers are willing

to step out of their bodies into the night,

to raise their arms and welcome the darkness,

palming the blank spaces, touching everything.

Always they return home safely, like blind men

who know it is morning by feeling shadows.

And always they wake up as themselves again.

That's why I want to say something astonishing

like: Our hearts are leaving our bodies.

Our hearts are thirsty black handkerchiefs

flying through the trees at night, soaking up

the darkest beams of moonlight, the music

if owls, the motion if wind-torn branches.

And now our hearts are thick black fists

flying back to the glove if our chests.

We have to learn to trust our hearts like that.

We have to learn the desperate faith of sleep-

walkers who rise out of their calm beds

and walk through the skin of another life.

We have to drink the stupefying cup of darkness

and wake up to ourselves, nourished and surprised.

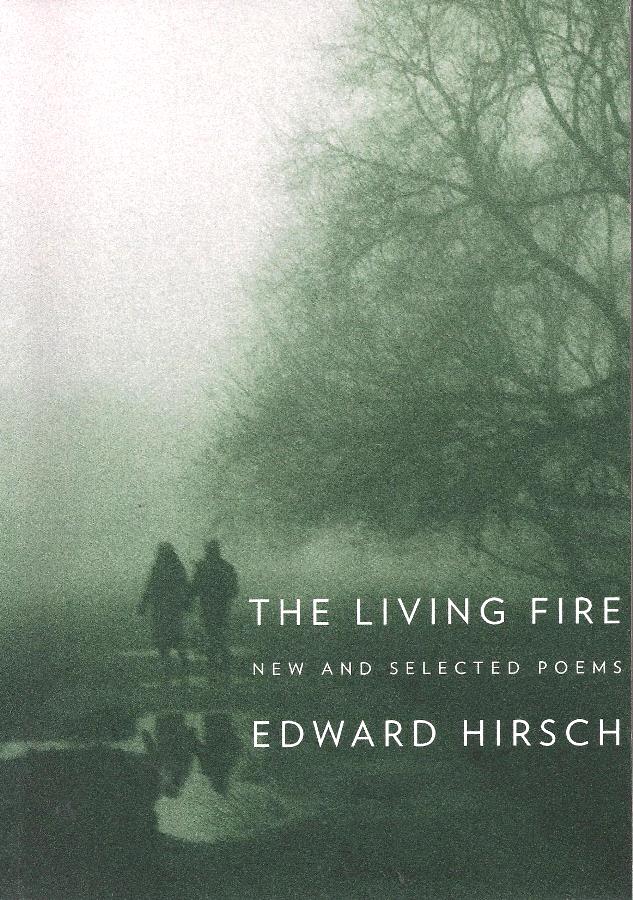

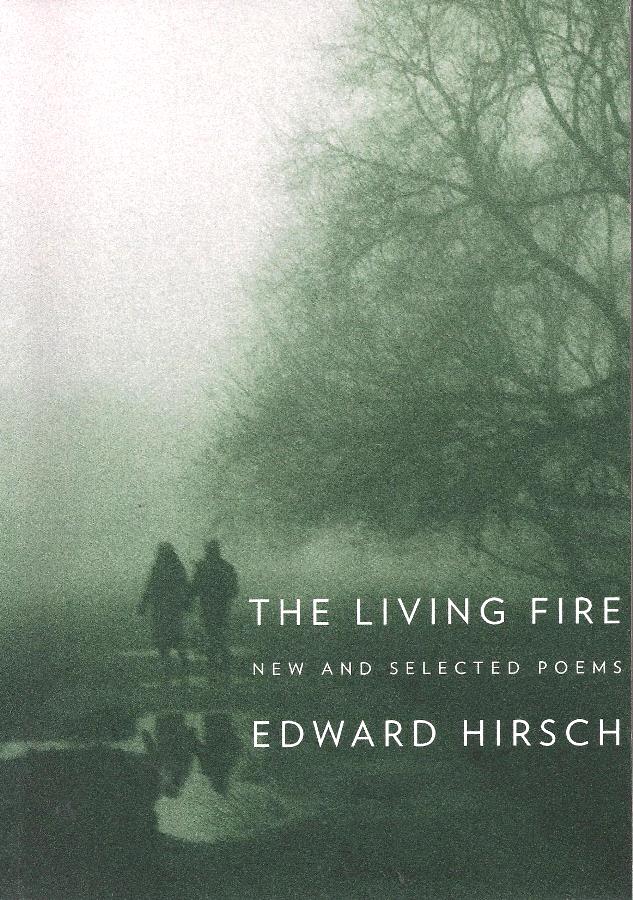

Edward Hirsch: The Living Fire

Đêm nay Gấu muốn phán một điều thật là

cực bảnh tỏng

Dành

cho những tên mộng du đặt quá nhiều niềm tin vào cặp

giò của chúng

Quá nhiều niềm tin vào sự vô hình

Vào... người đi qua tường

Mũi tên khắc

vào tấm thảm,

lối đi rách mòn đưa tới cầu thang thay vì cửa

sổ

lối cửa mở thay vì tấm gương liền

Gấu cực mê cái kiểu mà những tay mộng du

thèm bước ra khỏi cái túi thịt thối tha - từ

của Phật Giáo để gọi cái body thật thơm, thật ngon như múi

mít của… -

và đi vào đêm đen

Tay giơ lên chào mừng bóng tối

Gấu biết đến

tay này, là qua bài thơ tưởng niệm Brodsky. Sau

đó, chơi mấy cuốn của chả. Cực mê Simone Weil, và

mấy tay dính dáng tới Lò Thiêu.

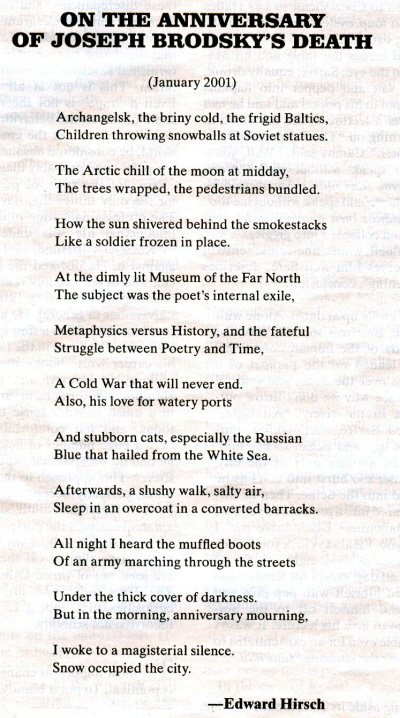

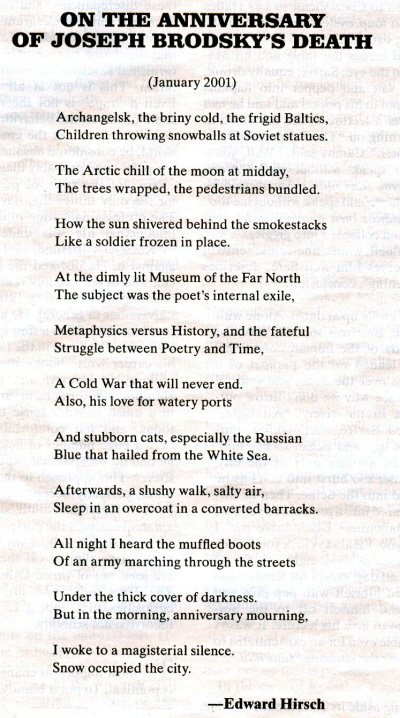

On the Anniversary of Joseph Brodsky’s Death

(January 2001)

Archangelsk,

the briny cold, the frigid Baltics,

Children throwing snowballs at Soviet statues.

The

Arctic chill of the moon at midday,

The trees wrapped, the pedestrians bundled.

How the

sun shivered behind the smokestacks

Like a soldier frozen in place.

At the

dimly lit Museum of the Far North

The subject was the poet’s internal exile,

Metaphysics

versus History, and the fateful

Struggle between Poetry and Time,

A Cold

War that will never end.

Also, his love for watery ports

And

stubborn cats, especially the Russian

Blue that hailed from the White Sea.

Afterwards,

a slushy walk, salty air,

Sleep in an overcoat in a converted barracks.

All

night I heard the muffled boots

Of an army marching through the streets

Under

the thick cover of darkness.

But in the morning, anniversary mourning,

I woke

to a magisterial silence.

Snow occupied the city.

-Edward

Hirsch.

NYRB, Feb 11, 2010

Tưởng niệm Brodsky nhân ngày mất

của ông

January 2001

Archangelsk, cái lạnh

mặn, những con người Baltic nhạt

Trẻ con ném những trái banh tuyết vô những

bức tượng Xô Viết

Cái ớn lạnh Bắc Cực của

mặt trăng vào giữa trưa

Cây bao, bộ hành cuộn.

Mặt trời rùng mình

sau những ống khói

Như một tên lính cứng lạnh ngay tại chỗ

Ở Viện Bảo Tàng Viễn Bắc

lù tù mù ánh đèn

Ðề tài là về cuộc lưu vong nội xứ của nhà

thơ

Siêu hình đấu với

Lịch sử, và

Cuộc chiến đấu thê lương giữa Thơ và Thời gian

Một Cuộc Chiến Lạnh chẳng hề

chấm dứt.

Thì cũng y chang tình yêu của nhà

thơ với những bến cảng sũng nước

Và những con mèo

bướng bỉnh, đặc biệt giống Nga

Xanh, tới từ Bạch Hải

Sau đó, là một

cuộc tản bộ lầy lội trong tuyết, trong không khí mặn mùi

muối

Ngủ trong áo choàng ở những trại lính đã

được cải tạo

Suốt đêm tôi nghe

có những tiếng giầy nhà binh bị bóp nghẹn

Của một đội quân diễn hành qua những con phố

Dưới cái vỏ thật là

dầy của đêm đen

Nhưng vào buổi sáng, cái buổi sáng

tưởng niệm,

Tôi thức giấc, bổ choàng

vào trong 1 sự yên lặng thật là quyền uy, hách

xì xằng.

Tuyết chiếm cứ thành

phố.

A Partial History Of My

Stupidity

By Edward Hirsch

Traffic was heavy coming off the bridge,

and I took the road to the right, the

wrong one,

and got stuck in the car for hours.

Most nights I rushed out into the evening

without paying attention to the trees,

whose names I didn't know,

or the birds, which flew heedlessly

on.

I couldn't relinquish my desires

or accept them, and so I strolled along

like a tiger that wanted to spring

but was still afraid of the wildness

within.

The iron bars seemed invisible to others,

but I carried a cage around inside

me.

I cared too much what other people

thought

and made remarks I shouldn't have made.

I was silent when I should have spoken.

Forgive me, philosophers,

I read the Stoics but never understood

them.

I felt that I was living the wrong

life,

spiritually speaking,

while halfway around the world

thousands of people were being slaughtered,

some of them by my countrymen.

So I walked on—distracted, lost in

thought—

and forgot to attend to those who suffered

far away, nearby.

Forgive me, faith, for never having

any.

I did not believe in God,

who eluded me.

Away from Dogma

I was prevented by a sort of shame from going

into churches ...

Nevertheless, I had three contacts with Catholicism

that really counted.

-SIMONE WElL

1. In Portugal

One night in Portugal, alone in a forlorn

village at twilight, escaping her parents,

she saw a full moon baptized on the water

and the infallible heavens stained with clouds.

Vespers at eventide. A ragged procession

of fishermen's wives moving down to the sea,

carrying candles onto the boats, and singing

hymns of heartrending sadness. She thought:

this world is a smudged blue village

at sundown, the happenstance of stumbling

into the sixth canonical hour, discovering

the tawny sails of evening, the afflicted

religion of slaves. She thought: I am

one of those slaves, but I will not kneel

before Him, at least not now, not with

these tormented limbs that torment me still.

God is not manifest in this dusky light

and humiliated flesh: He is not among us.

But still the faith of the fishermen's wives

lifted her toward them, and she thought:

this life is a grave, mysterious moment

of hearing voices by the water and seeing

olive trees stretching out in the dirt,

of accepting the heavens cracked with rain.

Edward Hirsch: The Living Fire

Tránh xa Tín điều

Tôi bị ngăn trở một cách tủi hổ không

được vô nhà thờ…

Tuy nhiên, tôi có được ba lần tiếp

xúc với Ca Tô Giáo, và điều này

thực sự đáng tính đếm tới

Simone Weil

1. Ở Portugal

Một đêm ở Portugal, một mình tại một ngôi

làng khốn khổ buồn bã vào lúc chập tối,

chạy trốn cha mẹ

Bà nhìn thấy một vừng trăng đầy được nước

rửa tội

Và những khoảng trời không thể sa xuống,

Điểm lấm tấm bởi những đám mây

Sao hôm ở với chiều hôm

Một chuyển động tả tơi

Là những bà vợ ngư phủ kéo nhau

xuống bãi biển

Mang những cây đèn cầy, trong những chiếc

thuyền

Và hát những bài thánh ca

thật là não lòng. Bà nghĩ:

Thế giới này là một ngôi làng

xanh mờ mờ

Vào lúc mặt trời lặn

Sự chấp nhận xẩy chân vào cái giờ

kinh điển thứ sáu

Khám phá ra những cánh buồm hung

hung vào lúc buổi chiều

Cái tôn giáo đau đớn của những kẻ

nô lệ.

Bà nghĩ:

Tôi là một trong những nô lệ

Nhưng tôi không quỳ gối trước Người

Ít ra vào lúc này

Không, với những chân tay bị hành

hạ này, vẫn còn hành hạ tôi

Chúa không hiển hiện trong thứ ánh

sáng lầm than như

thế này

Trong cái thân thể, thịt xương bị sỉ nhục

như thế này

Tuy nhiên niềm tin của những bà vợ ngư

phủ vẫn nhấc bổng Bà lên và,

Bà nghĩ:

Cõi đời này là một nấm mồ

Khoảnh khắc bí ẩn, nghe những giọng nói

bên bờ nước

Nhìn những cành ô liu vươn khỏi

bùn bụi

Và chấp nhận những khoảng trời vỡ vụn ra với

mưa.

Tưởng

Niệm

Tám Bó

What the Last Evening

Will Be Like

You're sitting at a small bay window

in an empty café by the sea.

It's nightfall, and the owner is locking up,

though you're still hunched over the radiator,

which is slowly losing warmth.

Now you're walking down to the shore

to watch the last blues fading on the waves.

You've lived in small houses, tight spaces-

the walls around you kept closing in-

but the sea and the sky were also yours.

No one else is around to drink with

you

from the watery fog, shadowy depths.

You're alone with the whirling cosmos.

Goodbye, love, far away, in a warm place.

Night is endless here, silence infinite.

Edward Hirsch: The Living Fire

Buổi chiều cuối cùng của Gấu

Cà Chớn

Gấu, tản mạn bên ly cà

phe

Ở cái cửa sổ ngó xuống 1 bãi biển

Đêm xuống

Chủ quán đóng cửa tiệm

Nhưng Gấu cứ ngồi lỳ bên cái lò sưởi

Đã mất dần hơi ấm

Và bi giờ Gấu bèn

đi 1 đường xuống bãi biển

Để chiêm ngưỡng 1 lần chót

Những đợt sóng màu xanh nhạt nhòa dần

Hẳn chúng biết thằng chả sắp đi xa, bèn... ăn

theo?

Mi đã từng sống trong những căn nhà xập xệ của Sài

Gòn

Những không gian bé tí –

Những bức tường cứ quây quanh mi –

Nhưng biển trời cũng vưỡn là của mi – và của Mai Thảo

nữa chứ!

Chẳng có thằng chó nào ở đây để cụng

ly với mi

Giữa mù sương của bạn quí của mi

Mi một mình với vũ trụ một

mình

Cả hai thì đều lộng gió!

Bye, bye, em lúc này mới xa vời làm sao, ấm

áp làm sao!

Đêm vô tận

vs

Đời của Gấu, đang tận.

Im lặng đồng đều, và đều vô cùng!

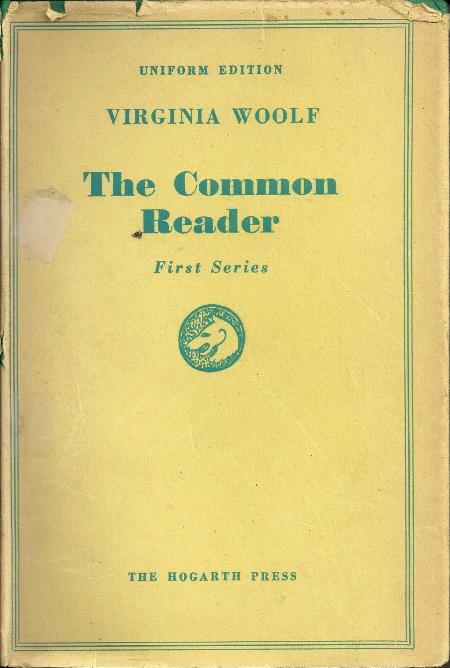

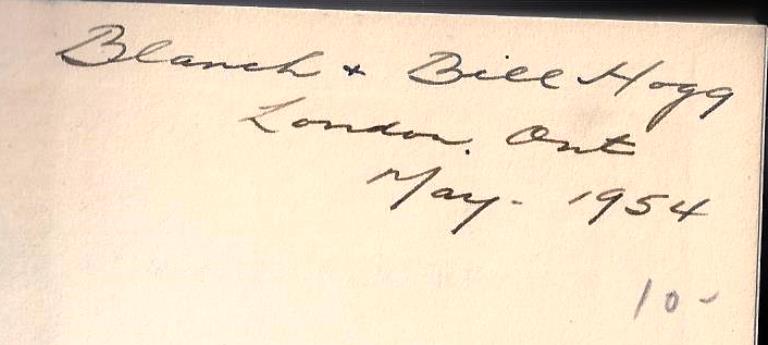

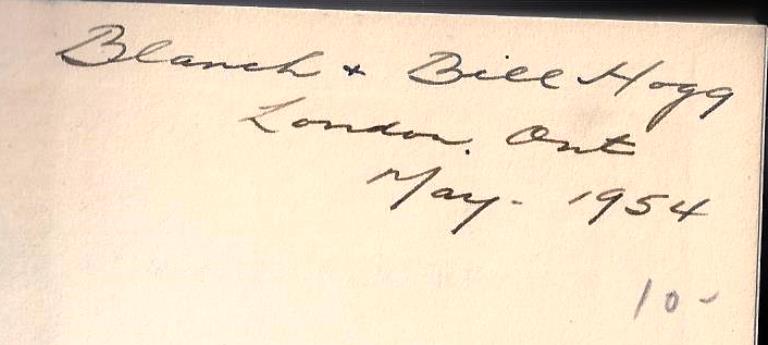

1954: Gấu lên

tầu Đệ Thất Hạm Đội, là cuốn sách đã nằm tại tiệm

sách cũ ở Toronto, chờ Gấu rồi!

1954: Gấu lên

tầu Đệ Thất Hạm Đội, là cuốn sách đã nằm tại tiệm

sách cũ ở Toronto, chờ Gấu rồi!

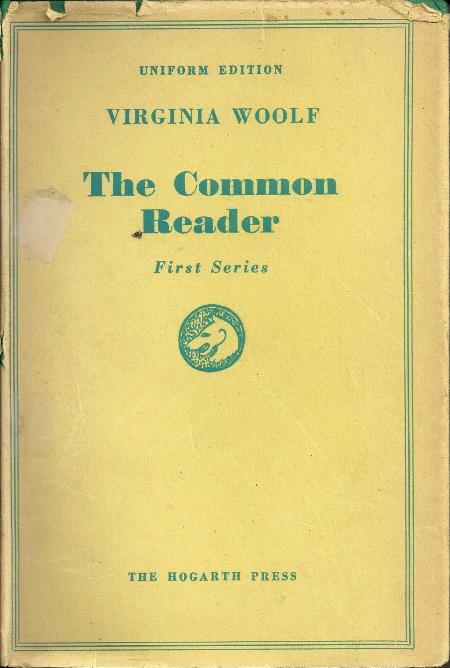

THE COMMON READER

THERE IS A SENTENCE in Dr. Johnson's Life of Gray which might well be

written up in all those rooms, too humble to be called libraries, yet full

of books, where the pursuit of reading is carried on by private people. "...

I rejoice to concur with the common reader; for by the common sense of readers,

uncorrupted by literary prejudices, after all the refinements of subtilty

and the dogmatism of learning, must be finally decided all claim to poetical

honors." It defines their qualities; it dignifies their aims; it bestows

upon a pursuit which devours a great deal of time, and is yet apt to leave

behind it nothing very substantial, the sanction of the great man's approval.

The common reader, as Dr. Johnson implies, differs

from the critic and the scholar. He is worse educated, and nature has not

gifted him so generously. He reads for his own pleasure rather than to impart

knowledge or correct the opinions of others. Above nil, he is guided by an

instinct to create for himself, out of whatever odds and ends he can come

by, some kind of whole-a portrait of a man, a sketch of an age, theory of

the art of writing. He never ceases, as he reads, to run up some rickety and

ramshackle fabric which shall give him the temporary satisfaction of looking

sufficiently like the real object to allow of affection, laughter, and argument.

Hasty, inaccurate, and superficial, snatching now this poem, now that crap

of old furniture, without caring where he finds it or of what nature it

may be so long as it serves his purpose and rounds his structure, his deficiencies

as a critic are too obvious to be pointed out; but if he has, as Dr. Johnson

maintained, some say in the final distribution of poetical honors, then,

perhaps, it may be worthwhile to write down a few of the ideas and opinions

which, insignificant in themselves, yet contribute to so mighty a result.

VIRGINIA WOOLF

Độc Giả.... Bèo

Độc giả bèo thì khác phê bình gia,

nhà học giả. Học vấn tệ, có khi chỉ là 1 tên

thợ máy nhà giây thép!

SONG

Bob Dylan's Nobel Prize

Christopher Ricks

TODAY,

THE happiest of turmoils all over the world. Rightly a tribute to the

art even more than to the artist, the Nobel triumph- like the art itself-will

endure. For the triumph of genius does the heart good, and not only the

heart.

Some reminders, since one of Dylan's powers

is that of a great reminder.

First, that every artist, insofar as he or

she is great as well as original, has had the task of creating the taste

by which the art is to be enjoyed (Wordsworth's conviction). Second, that

the art of song is a triple art, a true compound. And it doesn't make sense

to ask which element of a com pound is more "important": the voice, or

the music, or the words? (Which is more important in water, the oxygen

or the hydrogen?) And that therefore there is a danger, even while we are

very grateful this time to the Nobel Committee, if we simply allocate Dylan's

art of song to literature or Literature, of our privileging the

words, as though song were not a tri- angle and often an equilateral triangle.

This danger is one that those of us who have written in praise of Dylan's

greatness with words-or have edited The Lyrics, complete with sung variants

(as Lisa and Julie Nemrow and I have done)-have not been able to escape,

have even had to court. A danger, and a deficiency, all the same and all

the time. For literature is best thought of -most of the time-as the

art of a single medium, language. Nothing grudging about this, but a reminder

that there are a great many profound achievements for which there is no Nobel

prize. Music, for a start. Or the performing art that is acting, for another,

Dylan being a great vocal actor and enactor.

A performer of genius, Dylan is necessarily

in the business (and the game) of playing his timing against his rhyming.

The cadences, the voicing, the rhythmical draping and shaping don't make

a song superior to a poem, but they do change the hiding places of its

powers. Or rather, they add to the number of its hiding places. I'd not

have written a book about Dylan, to stand alongside books on Milton and

Keats, Tennyson and T.S. Eliot, if I didn't think Dylan a genius of and

with language. But let's not forget, in the delight of this moment (of great

moment), those other aspects, not strictly Literary, of his genius, sharing

in the constitution of his art. When Eliot wrote the line "To the drift

of the sea and the drifting wreckage," it was a creation of words only

(though not merely). When Dylan sings "condemned to drift or else

be kept from drifting," he compounds it all, with voice and music joining

with words within a different drift and drive. And his drive?

Why are you doing what you're doing? [Pause]

"Because I don't know anything else to do. I'm good at it."

How would you describe "it"?

"I'm an artist. I try to create art."

More than try. The Nobel citation speaks of Dylan as "having

created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition."

More, even, than that. +

-October 13,2016

https://www.threepennyreview.com/current.html

Note: Hai

bức hình, kèm bài viết. Hai bài thơ sau đây,

cùng số báo.

Quatrains from the Clinic

Tứ khúc ở nhà thương Grall [Đồn Đất, Sgn]

Mai thôi làm việc. Khi

chúng tôi chia tay nhau tại cầu thang, trong khi chờ thang

máy, đột nhiên nàng nói: "Tôi sợ, tôi

sợ lắm", nàng nói câu đó bằng tiếng Pháp.

Tôi mở cửa thang máy cho nàng và bỗng chợt

nhớ câu tôi hỏi vị bác sĩ người Pháp chữa trị

cho tôi, khi còn nằm trong nhà thương Grall:

Như vậy là chiến tranh đã

chấm dứt đối với tôi? (Est-ce que la guerre est finie pour moi?).

Tôi chờ đợi khi ra khỏi nhà

thương, khi đứng ở trước cổng nhà thương Grall nhìn ra

ngoài đời và khi đó chiến tranh đã

hết.

They wait for me-in wheelchairs, painfully,

or sometimes I imagine scared, or high

because they cannot bear it, naked thighs

exposed by paper gowns. They wait for me

while reading pamphlets on mammography,

or tattered, long-outdated magazines,

or maybe just the posters for vaccines

that promise if they follow what we say

they might live longer, long enough at least.

They wait for me, their palpitations racing,

their ghostly blood pressures silently rising,

their stomachs grumbling since they're told to fast,

their headaches like a sledgehammer. They wait

for me, their vision blurred, their hearing lost,

their appetites diminished. Baring breasts,

assessing wounds, I know that I'm too late.

-Rafael Campo

The Capacity of Speech

It is easy to be decent to speechless things.

To hang houses for the purple martins

To nest in. To bed down the horses under

The great white wing of the year's first snow.

To ensure the dog and cat are comfortable.

To set out suet for the backyard birds.

To put the poorly-shot, wounded deer down.

To nurse its orphaned fawn until its spots

Are gone. To sweep the spider into the glass

And tap it out into the grass. To blowout

The candle and save the moth from flame.

To trap the black bear and set it free.

To throw the thrashing brook trout back.

How easy it is to be decent

To things that lack the capacity of speech,

To feed and shelter whatever will never

Beg us or thank us or make us ashamed.

|

Trang NQT

art2all.net

Lô

cốt

trên

đê

làng

Thanh Trì,

Sơn Tây

|

|