|

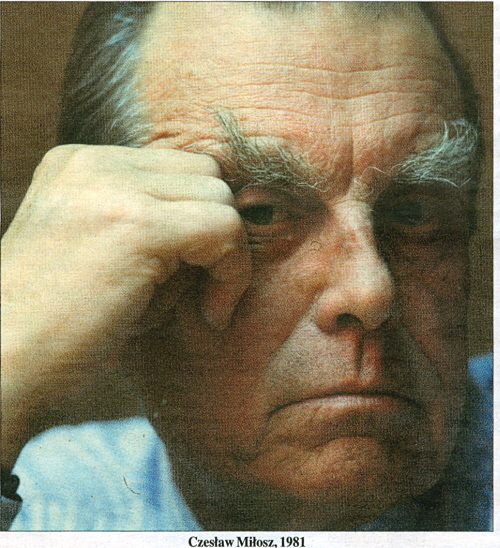

Kỷ niệm 100 năm sinh của Milosz The wiles

of art Guilt and greatness in the life of

Czeslaw Milosz CLARE CAVANAGH Note:

Bài viết trên TLS, Nov 25, 2011. Clare Cavanagh, chuyên gia tiếng Ba

Lan, giáo

sư Slavic languages tại Đại học North-western University, chuyên dịch

thơ Adam

Zagajewski, Wislawa Szymborska, Czeslaw Milosz. Viết phê bình thơ cũng

bảnh

lắm. Bài viết thật tuyệt, về nhà thơ “bửn”, (1) [wiles of art: mưu ma

chước quỉ

của nghệ thuật] của thế kỷ, và nếu không bửn, chắc gì đã được Nobel văn

chương? (1) Đây

là muốn nhắc tới bài viết ngắn “To Wash” của ông. Ký

tên: HC! Đọc bài viết

là thể nào cũng nghĩ đến những nhà thơ Bắc Kít của chúng ta, và… TCS: Milosz's shame and his strength go hand in hand. As his dates suggest - he was born in a remote comer of the Russian Empire in 1911 and died in post-Communist Cracow in 2004 - he was a survivor. He wrote to survive, and he survived to write. But he came from a part of the world and a tradition where poet-survivors are suspect: oppressed nations fostered on Romantic traditions favor martyrs over Nobel Prize-winning nonagenarians. A wartime acquaintance recalls Milosz insisting that "he didn't intend to fight since he had to survive the war: his task was writing and not battle, his likely death would serve no purpose, while his writing was important for Poland".

The wiles

of art Tội Lỗi và Sự Lớn Lao trong cuộc đời Czeslaw The wiles of

art Guilt and

greatness in the life of Czeslaw Milosz CLARE

CAVANAGH

"I am

Milosz, I must be Milosz, / Being Milosz, I don't want to be Milosz, /

I kill

the Milosz in myself so as / To be more Milosz." Witold Gombrowicz's

lines

describe not only the plight of its famous subject, but the

difficulties facing

his would-be biographers as well. And Gombrowicz didn't know the half

of it.

His comment dates from 1952; Czeslaw Milosz had just broken with the

Polish

Communist government, and was destined to spend what he later called

"the

hardest decade" of a tumultuous life in exile in France. But he still

had

more than five decades of self-contradiction ahead of him with which to

baffle

countrymen and admirers alike. Czeslawa Milosza

autoportret

przekorny

(1994,

Czeslaw Milosz's Perverse Self-Portrait) is the title of a revealing

book

length series of interviews that the scholar Aleksander Fiut conducted

with

Milosz between 1979 and 1990. "How did he get me to tell him so

much?", the poet later complained. Milosz was notoriously averse to

self-revelation. He disdained the confessional strain that dominated so

much

postwar American poetry: a true poet kept his demons to himself, he

insisted.

"Whenever Robert Lowell landed in a clinic I couldn't help thinking

that

if someone would only give him fifteen lashes with a belt on his bare

behind,

he'd recover immediately", he writes in A Year of the Hunter (1994; Rok

mysliwego, 1990). He is more charitable in a late poem. "I had no right

to

talk of you that way / Robert", he confesses. "I used to walk upright

to hide my affliction. / You didn't have to." What was the affliction

that

plagued Milosz? Concealment and self-reproach run through the later

work

particularly. "I know that in me are pride, desire, I and cruelty, and

a

grain of contempt", he writes in an un translated early poem. What

might

seem the youthful clichés of a poète maudit in the making gain weight

through

decades of repetition. "This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine",

he seems to admit, with Prospero, in

the title poem of his collection To

(2000, This): "If I could at last

tell you what is in me, / If I could shout: people! I have lied by

pretending

it was not there". But the confession is carefully couched in the

conditional: we never find out exactly what "this" is. "Writing

has been for me a protective strategy/Of erasing traces", he explains

in

the same poem. Friends and admirers have wondered for years: what sins

did he

spend a lifetime trying to erase? Andrzej Franaszek's magnificently

researched

Milosz: Biografia, published earlier this year in Poland, gives as

close to a

definitive answer as we can reasonably hope for. There is no single

secret, no

hidden crime. The affliction goes hand in hand with the artistry, as

"This" suggests: "Only thus was I able to describe your

inflammable cities / Brief loves, games disintegrating into dust". And

the

self-contempt, the "shame of failing to be I What I should have been"

("To Raja Rao", 1969), meets its match in Milosz's deep ambivalence

towards the extraordinary body of work he spent a lifetime expanding,

revisiting and revising. "What is poetry", he famously asks in

"Dedication" (1945): "A connivance with official lies, / A song

of drunkards whose throats will be cut in a moment, / Readings for

sophomore

girls". The art and

the self were never enough. Enough for what? Yet another of Milosz's

quasi-confessions provides clues: "I think I would fulfill my life /

Only

if I brought myself to make a public confession / Revealing a sham, my

own, and

that of my epoch", he admits in "A Task" (1970). His life and

that of his age: the two conjoined in his mind early on. "Who is a

poet?", Thomas Mann asks, and the answer he provides might be taken

from

Milosz's own writings: "He whose life is symbolic". "Tomorrow at

the latest I'll start working on a great book [dzielo] / In which my

century

will appear as it really was", he promises in "Preparation"

(1986). He had in

fact begun that book - which would span volumes, genres, nations and

decades -

much earlier. "Folly, the absurdity of phenomena, theories, beliefs,

drives. Of these writing is the least ridiculous. Such is the mood of a

young

man perfectly prepared to face History", the twenty-two-year-old writer

tells his early mentor, the poet Jaroslaw Iwaszkiewicz, only

half-ironically.

He directed his aspirations early on to writing the kind of mystical,

heterogeneous book (ksiega) he describes in an early essay (1938) on

his

distant cousin, the French-Lithuanian poet Oscar Milosz: "The Bible ...

the Divine Comedy, Faust .... These are books concealing a wisdom as

complete

as it is possible for a person to attain, books of the initiated".

Oscar

Milosz, an admirer of Shelley and Byron, adhered to the Romantic notion

of the

"poet as a legislator of the collective imagination", and his young

apprentice followed his lead. Even the difficult decades spent a

continent away

from his native Lithuania, he wrote a half-century later, answered the

prayers

of a "boy who read the bards and asked for greatness which means

exile" ("The Wormwood Star", 1977-8). "My

life story is one of the most astonishing I have ever come across",

Milosz

writes in his ABC's (2001; Abecadlo Milosza, 1997-8). This story, as he

tells

and retells it in the work, is both a spiritual pilgrimage and an

extraordinary

picaresque. The 959 pages of Franaszek's biography are scarcely enough

to tell

it. "You can't put it down", friends in Poland told me time and

again, and they were right. Milosz "wants to become the biographer of

his

own talent", a skeptical colleague remarked of the brilliant young poet

in

interwar Vilnius. He became the biographer of much more; one might

follow the

poet's own lead in "making of Milosz's biography a tale of initiation,

whose hero penetrates all the mysteries of the twentieth century",

Franaszek comments. "My

age", "my era", "my epoch", "my century":

the phrases punctuate Milosz's later work particularly. The young poet

who

claimed to be ready for History had no idea. Even the

most abbreviated list of places and names that run through the

biography -

rural Lithuania, the Tran-Siberian Railway, revolutionary Russia,

interwar

Paris, Nazi-occupied Warsaw, the Polish Embassy in post-war Washington,

DC,

Berkeley in 1968, Stockholm in 1980, People's Poland in 1981,

post-Communist

Poland a decade later, W. H. Auden, Hannah Arendt, Albert Camus, Albert

Einstein,

T. S. Eliot, Karl Jaspers, Thomas Merton, Pablo Neruda, Ronald Reagan,

Jean-Paul Sartre, Paul Valery, Lech Walesa, Karol Wojtyla - reads like

a Who's

Who, and a Where's Where, of the century just past. And this is to say

nothing

of the less recognizable human histories Milosz carefully preserved

from

anonymity: "Still in my mind [I try] to save Miss Jadwiga", he writes

of one wartime recollection: A

little hunchback, librarian by profession, Who

perished in the shelter of an apartment house That was considered safe

but

toppled down And no one was able to dig through the slabs of wall,

Though

knocking and voices were heard for many days. ("Six Lectures in

Verse", 1985). That

knocking and those voices haunt the poetry and prose alike. Milosz's

shame and his strength go hand in hand. As his dates suggest - he was

born in a

remote comer of the Russian Empire in 1911 and died in post-Communist

Cracow in

2004 - he was a survivor. He wrote to survive, and he survived to

write. But he

came from a part of the world and a tradition where poet-survivors are

suspect:

oppressed nations fostered on Romantic traditions favor martyrs over

Nobel

Prize-winning nonagenarians. A wartime acquaintance recalls Milosz

insisting

that "he didn't intend to fight since he had to survive the war: his

task

was writing and not battle, his likely death would serve no purpose,

while his

writing was important for Poland". His decision to sit out the Warsaw

Uprising against the Nazis another great poet, Krzysztof Kamil

Bacczynski, died

on the barricades at the age of twenty-three - still provoked heated

arguments

at recent centennial events in Poland. His brief affiliation with the

Soviet-backed government after the war - though he never became a Party

member

- haunted him to the end. I remember him agonizing, in 2002, over a

younger

poet's charge that he had spent the post-war years as "Moscow's dancing

bear". His break

with the Party in 1951 was no less controversial. "But you're a

deserter.

/ But you're a traitor": the poet Konstanty Galczynski voiced the party

line in his notorious "Epic for a Traitor" (1953). Milosz became an

official non-person in People's Poland shortly thereafter. The

situation in

Paris was not much better. The émigré community despised the former

sympathizer, while pro-Soviet intellectuals such as Sartre spurned the

apostate. The uprising, the Communist takeover, the break with the

regime, and

an uncertain exile: these traumas initiated a remarkably productive

decade that

saw the making of Milosz's international reputation with the

publication of his

classic Captive Mind (Zniewolony umyst, 1953), as well as essays, two

novels,

his volume Swiatlo dzienne (1953, Daylight) and his Treatise on Poetry

(Traktat

poetycki, 1957). The periodic "Milosz affairs" that punctuated his

life seem to have spurred his already formidable creative energies. In his later

writings, Milosz often casts himself as Foolish Jack, the younger

brother in

the fairy tales who muddles every move, but marries the king's daughter

in the

end. He found an even less likely alter ego in his later years. "You

cannot write my biography!" he told me two years before his death (he

had

already authorized me to do an English-language version). "But it's too

late!" I told him, shocked. "I've already spent the advance!"

"Then you must make it a comedy", he responded. "It's the story

of Forrest Gump." I'd handed him the set-up he'd been waiting for, and

he

roared at his own joke. His life had

been shaped, so he thought, by luck or fate: "Perhaps I was born so

that

the 'Eternal Slaves' might speak through my lips", he intones near the

end

of Captive Mind. For his less forgiving countrymen, at home and abroad,

egotism

and opportunism were common charges. How had he managed to land on his

feet

time and again? International success, a long, complicated life, and an

irresistible impulse to play the gadfly meant that even his triumphal

return to

Poland in his last years met with mixed reactions. Fireworks over

Cracow's

Wawel Castle marked his ninetieth birthday. On a smaller scale, a taxi

driver

gasped when he recognized Milosz's home from the street address I gave

him a

year later. "He hasn't been feeling well, has he?", he asked, and

passed on best wishes from the "cabbie in the red Mercedes". But

Milosz's public support for a local gay rights parade shortly before

his death

led to yet another round of pro-Communist and anti-Catholic charges,

charges

that resurfaced as his family struggled to have him buried in the

Paulinist

Crypt in Cracow. The official government announcement of the current

"Year

of Milosz" sparked further protests. "What are you going to see him

for?" a ticket-taker scornfully asked one recent visitor to the tomb. "How

could he do it? Knowing what we know / About his life, every day aware

/ Of

harm he did to others", Milosz writes in "Biography of an

Artist" (1995). He may have seemed fate's undeserving favorite to many

compatriots, and to himself at times. But a darker model also shaped

his vision

of his life in art. "I have not progressed, in my religion, beyond the

Book of Job, / With the one difference that Job saw himself as

innocent",

he confesses in "A Treatise on Theology" (2002). Job's family was

punished for his righteousness, while Milosz' s family paid the price,

so he

thought, for his dedication to his writing. "A good man will not learn

the

wiles of art": the sentiment recurs throughout the mature work. "I was

essentially a man of short-lived passions, visions and dreams, not fit

material

for a husband and father", Milosz mourns in the "Materials for My

Biography" (undated) that Andrzej Franaszek uncovered among the poet's

voluminous unpublished writings. Milosz's marriage to his brilliant,

acerbic

first wife, Janina Dluska, produced two sons and lasted fifty years,

surviving

the separations, infidelities and physical and mental illnesses that

Franaszek

describes in sympathetic, un-emphatic detail. The family's struggles,

the

isolation, the scant readership on both sides of the Atlantic: these

troubles

took Milosz and his life story in a distinctive direction in the 1970s.

For William

Blake, "every true poet must spend his life making the Bible anew",

Lawrence Lipking comments in The Life of the Poet (1981). Milosz outdid

his

beloved Blake by learning Hebrew and Greek in his sixties. He aspired

to

translate the Bible into Polish for the first time from the original

tongues,

not Latin (he managed only 700 pages). He tackled Job early on, and his

translator’s preface shows how closely he linked the story to his own

fate.

Long suffering, his own and others', exile from his childhood home,

moral

failings, the price for prophecy, the century's hard history: "my

imagination cannot make peace with Job's lament within me", he

comments. The volume

of biblical translations in the Polish Collected Works suggests the

limits of

the Milosz who is so widely admired in the English-speaking world. The

translations that intermingle with original work - though he would have

resisted the distinction - in the Polish collections have vanished from

their

English-language counterparts. More than this: the metrical innovator,

who

absorbed and transmuted forms not just from the Polish, but the French

and

Anglo-American traditions with breathtaking facility, likewise largely

goes

missing. And this is chiefly Milosz's own doing. Unlike his friend and

fellow

émigré Joseph Brodsky, he refused to sacrifice sense for structure in

translation,

and generally left his most intricately structured work un-translated

or

translated it into free verse, as in The Treatise on Poetry. His

exquisite

version, with Robert Pinsky, of the "Song on Porcelain" (1947), gives

hints of the poet who is Milosz at his best for many Polish readers. The Nobel

Prize not only brought him back to life in Poland; the government could

no

longer keep his work from finding its way into print. It also gave him

the

opportunity to rewrite the story of his life for the new audience the

prize had

brought him. And rewrite it he did. To give just one example: perhaps

his

best-known collection, the volume known in English as Rescue (Ocalenie,

1945),

is just about half the length of its Polish counterpart. The tale it

tells of the evolving poet, who discovers too late the "salutary aim"

of "good poetry" is thus oddly - strategically? - truncated in

English. The great poet spends a lifetime rewriting and revising the

great Book

of his story in art, Lipking argues. "The past is never closed down and

receives the meaning we give it by our subsequent acts", Milosz

comments

in a late poem. Few poets have had the chance to re-create their past

in art in

another language for a new public as Milosz did in his last decades.

The disparities

between the tales he tells in English and Polish are revealing in ways

that

remain to be explored. The

complexities of Milosz's Polish-Lithuanian past may elude most

Anglophone

readers. But his forty years in Californian exile remain equally opaque

to his

Polish audience. They received short shrift in the centennial events I

attended

in recent months. My defence of Milosz as, inter alia, an American and

even a

Californian poet took Polish specialists aback. "I thought his America

was

just [Henry] Miller's 'air-conditioned nightmare''', one scholar

commented. But

Milosz's - typically volatile - relationship with American culture far

predates

his first visit to the United States. "I was raised in large part on

American literature", he recalls in A Perverse Self-Portrait. As a

child,

he loved his abridged, one-volume translation of James Fennimore

Cooper's

Leather stocking Tales: little Czeslaw played at Natty Bumppo in the

Lithuanian

woods. When the young poet discovered Walt Whitman some years later,

his reaction

was immediate: "Revelation: to be able to write as he did!". His appetite

for American literature and history continued unabated throughout his

years in

exile. Milosz was an inveterate researcher and often did his homework

on the

road: in one lovely footnote, Franaszek lists the various Volvos,

Dodges, and

Pontiacs the Milosz family wore out. The road trips, the reading and

the

"wondrously quick eyes" Milosz recalls in a late poem combine to make

him an astute interpreter of the West's landscapes and hidden histories

in his

poetry and prose alike. As his friend, the poet Jane Hirshfield

comments,

"he loved California enough to argue with it". "He would like to be one, but he is a self-contradictory multitude", Milosz writes in ''The Separate Notebooks" (1977-9). Pole, Lithuanian, Californian, poet, essayist, novelist, historian, metaphysician, translator, scholar, anti-confessional autobiographer, Job, Gump and Foolish Jack: how can they be reconciled? The short answer is: they can't. The poet of "Song of a Citizen" (1943) imagines his ideal bardic fate from wartime Warsaw: "In my later years, / Like old Goethe to stand before the face of the earth, / And recognize it and reconcile it / With my work built up, a forest citadel/on a river of shifting lights and brief shadows". The lights and shadows mingle throughout the life's work Milosz built up, in multiple languages and genres, over the course of his century. But his is no citadel. The work, like the life, is both overwhelming and endlessly approachable, since this master of self-contradiction resisted final systems even as he struggled to create them. "Why do I still have so many doubts at my age?", he asked in a late conversation. We are lucky to have had a doubter of such prodigious gifts in our midst. |