|

THE

IMPORTANCE OF SIMONE WElL FRANCE

offered a rare gift to the contemporary world in the person of Simone

Weil. The

appearance of such a writer in the twentieth century was against all

the rules of

probability, yet improbable things do happen. The life of

Simone Weil was short. Born in 1909 in Paris, she died in England in

1943 at

the age of thirty-four. None of her books appeared during her own

lifetime.

Since the end of the war her scattered articles and her

manuscripts-diaries,

essays-have been published and translated into many languages. Her work

has

found admirers all over the world, yet because of its austerity it

attracts

only a limited number of readers in every country. I hope my

presentation will

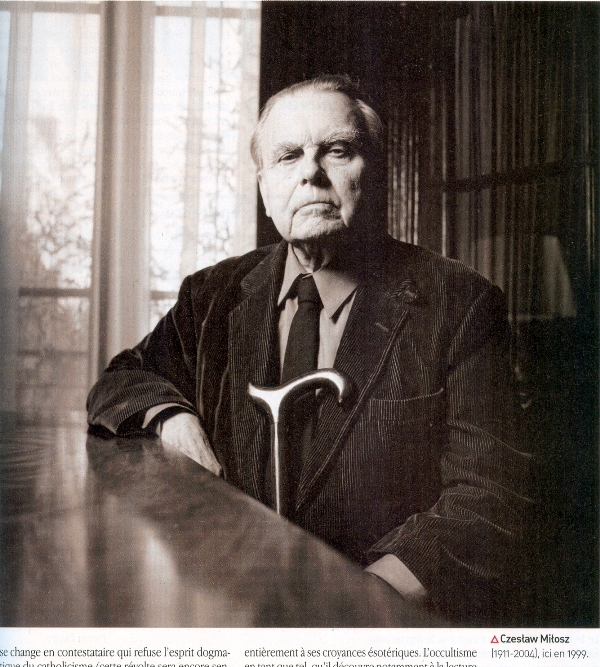

be useful to those who have never heard of her. [suite] Czeslaw MiloszKỷ niệm

100 năm sinh của Milosz

Le poète

intraitable Il ne peut

toutefois adhérer au marxisme: la lecture de Simone Weil (qu'il traduit

en

polonais) a joué à cet égard un rôle capital dans son évolution

intellectuelle.

Elle aura été la première à dévoiler la contradiction dans les termes

que

représente le « matérialisme dialectique ». Pour une pensée

intégralement

matérialiste (comme celle d'Engels), l'histoire est le produit de

forces

entièrement étrangères à l'individu, et l'avènement de la société

communiste, une

conséquence logique de l'histoire; la liberté n'y a aucune place. En y

introduisant la « dialectique ", Marx réaffirme que l'action des

individus

est malgré tout nécessaire pour qu'advienne la société idéale: mais

cette

notion amène avec elle l'idéalisme hégélien et contredit à elle seule

le

matélialisme. C'est cette contradiction qui va conduire les sociétés «

socialistes" à tenir l'individu pour quantité négligeable tout en

exigeant

de lui qu'il adhère au sens supposé inéluctable de l'histoire. Mais la

philosophie de Simone Weil apporte plus encore à Milosz que cette

critique:

elle lui livre les clés d'une anthropologie chrétienne qui, prolongeant

Pascal,

décrit l'homme comme écartelé entre la « pesanteur" et la « grâce ". Nhà thơ

không làm sao “xử lý” được. Tuy nhiên,

ông không thể vô Mác Xít: Việc ông đọc Simone Weil [mà ông dịch qua

tiếng Ba

Lan] đã đóng 1 vai trò chủ yếu trong sự tiến hóa trí thức của ông. Bà

là người

đầu tiên vén màn cho thấy sự mâu thuẫn trong những thuật ngữ mà chủ

nghĩa duy vật

biện chứng đề ra. Ðối với một tư tưởng toàn-duy vật [như của Engels],

lịch sử

là sản phẩm của những sức mạnh hoàn toàn xa lạ với 1 cá nhân con người,

và cùng

với sự lên ngôi của xã hội Cộng Sản, một hậu quả hữu lý của lịch sử; tự

do chẳng

hề có chỗ ở trong đó. Khi đưa ra cái từ “biện chứng”, Marx tái khẳng

định hành

động của những cá nhân dù bất cứ thế nào thì đều cần thiết để đi đến xã

hội lý

tưởng: nhưng quan niệm này kéo theo cùng với nó, chủ nghĩa lý tưởng của

Hegel,

và chỉ nội nó đã chửi bố chủ nghĩa duy vật. Chính mâu thuẫn này dẫn tới

sự kiện,

những xã hội “xã hội chủ nghĩa” coi cá nhân như là thành phần chẳng

đáng kể, bọt

bèo của lịch sử, [như thực tế cho thấy], trong khi đòi hỏi ở cá nhân,

phải tất

yếu bọt bèo như thế. Nhưng triết học của Simone Weil đem đến cho Milosz

quá cả

nền phê bình đó: Bà đem đến cho ông những chiếc chìa khoá của một nhân

bản học

Ky Tô, mà, kéo dài Pascal, diễn tả con người như bị chia xé giữa “trọng

lực” và

“ân sủng”. Chúng ta phải

coi cái đẹp như là trung gian giữa cái cần và cái tốt (mediation

between

necessity and the good), giữa trầm trọng và ân sủng (gravity and

grace). Milosz

cố triển khai tư tưởng này [của Weil], trong

tác phẩm “Sự Nắm Bắt Quyền Lực”, tiếp theo

“Cầm Tưởng”. Đây là một

cuốn tiểu thuyết viết hối hả, với ý định cho tham dự một cuộc thi văn

chương,

nghĩa là vì tiền, và cuối cùng đã đoạt giải! Viết hối hả, vậy mà chiếm

giải,

nhưng thật khó mà coi đây là một tuyệt phẩm. Ngay chính tác giả cũng vờ

nó đi,

khi viết Lịch Sử Văn Học Ba Lan. Tuy nhiên, đây là câu chuyện của thế

kỷ. Nhân

vật chính của cuốn tiểu thuyết tìm cách vượt biên giới Nga, để sống

dưới chế độ

Nazi, như Milosz đã từng làm như vậy. THE

IMPORTANCE OF SIMONE WElL FRANCE

offered a rare gift to the contemporary world in the person of Simone

Weil. The

appearance of such a writer in the twentieth century was against all

the rules of

probability, yet improbable things do happen. The life of

Simone Weil was short. Born in 1909 in Paris, she died in England in

1943 at

the age of thirty-four. None of her books appeared during her own

lifetime.

Since the end of the war her scattered articles and her

manuscripts-diaries,

essays-have been published and translated into many languages. Her work

has

found admirers all over the world, yet because of its austerity it

attracts

only a limited number of readers in every country. I hope my

presentation will

be useful to those who have never heard of her. [suite] Czeslaw

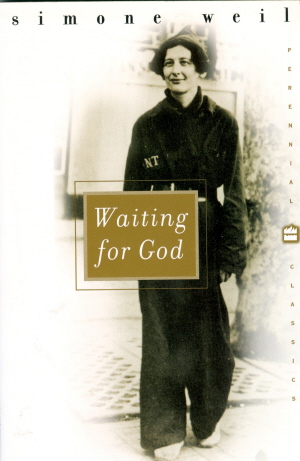

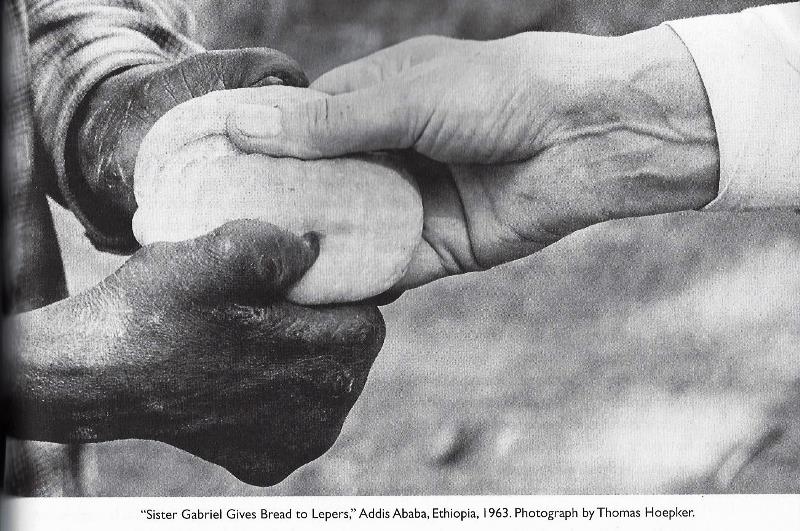

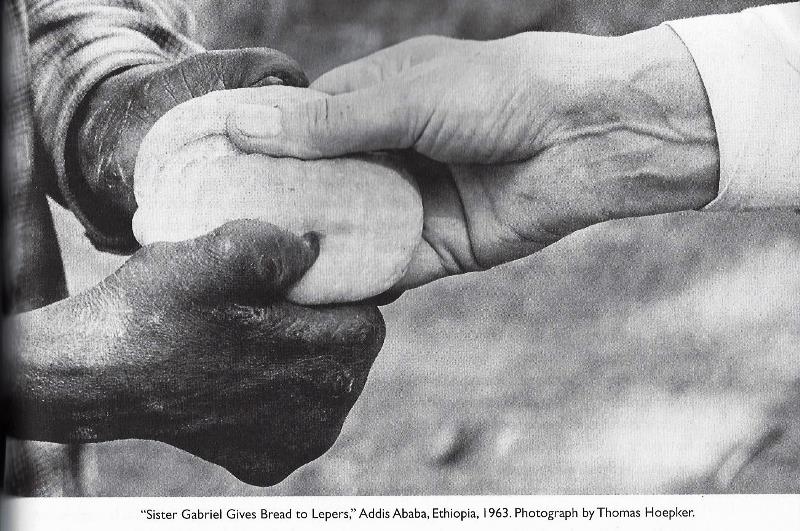

Milosz  Trong số báo

về Lòng Từ Thiện, có bài của Simone Weil, trích từ The Need for Roots. Trong tiểu

sử của bà, có trích dẫn một câu, của Susan Sontag, viết về Weil: [From The

Need for Roots]. Born in Paris in 1909, Weil dedicated her lift to

advocating

for the poor and disenfranchised. She worked as a teacher, trained with

an

anarchist unit during the Spanish Civil War, and once debated Leon

Trotsky in

her parents' apartment after arranging for him to hold a clandestine

meeting

there. Weil's uncompromising asceticism led Susan Sontag to declare,

"No

one who loves life would wish to imitate her dedication to martyrdom."

The

bulk of Weil's writing was published only after her death from

tuberculosis in

1943. Gấu không nghĩ là cái tay “viết lại” Kẻ Xa Lạ và được Goncourt năm nay, hiểu được Camus. Tư tưởng của Camus, là từ Weil mà ra, (b) và Weil, như Susan Sontag, viết ở trên, cho rằng, chẳng ai dám bắt chước Weil, nếu kẻ đó còn yêu cuộc đời này! Bất giác lại nhớ tới lời

phẩm bình của vị thân hữu của TV. Vị này giải

thích,

Camus đẹp trai quá, “gái” nhiều quá, làm sao bắt chước cái khổ hạnh ghê

gớm như

của Weil! Có 1 cái gì

cực kỳ ngược ngạo, và hình như lại bổ túc cho nhau, giữa câu của Weil,

khi nhìn

những đoàn quân Nazi tiến vào Paris, và của TTT, khi nhìn VC Bắc Kít vô

Saigon. (b) Violent in

her judgments and uncompromising, Simone Weil was, at least by

temperament, an

Albigensian, a Cathar; this is the key to her thought. She drew extreme

conclusions from the Platonic current in Christianity. Here we touch perhaps

upon hidden ties between her and Albert Camus. The first work

by Camus was his

university dissertation on Saint Augustine. Camus, in my opinion, was

also a

Cathar, a pure one, and if he rejected God it was out of love for God

because

he was not able to justify Him. The last novel written by Camus, The

Fall, is

nothing else but a treatise on Grace-absent grace-though it is also a

satire:

the talkative hero, Jean-Baptiste Clamence, who reverses the words of

Jesus and

instead of "Judge not and ye shall not be judged" gives the advice

"Judge, and ye shall not be judged," could be, I have reasons to

suspect, Jean-Paul Sartre.  Susan Sontag Note: Bài viết

cách đây 50 năm, nhân kỷ niệm 50 năm NYRB, bèn cho đăng lại. Susan

Sontag không

đọc được Simone Weil. Cách nhìn của bà thua cả Gấu, đó là sự thực. Steiner,

Milosz, đọc Simone Weil, "đốn ngộ" hơn nhiều. Trên TV đã dịch bài của

Steiner. Gấu sẽ đi tiếp bài của Milosz, "Sự quan

trọng

của Simone Weil", in trong “To Begin Where I Am”. Trong cuốn này, có

mấy

bài thật là tuyệt. Bài essay, sau đây, chỉ cái tít không thôi, đã chửi

bố mấy đấng

VC đứng về phe nước mắt: Sontag chỉ

chịu nổi cuốn sau đây của Simone Weil:

The

principal value of the collection is simply that anything from Simone

Weil’s

pen is worth reading. It is perhaps not the book to start one’s

acquaintance

with this writer—Waiting for God, I

think, is the best for that. The originality of her psychological

insight, the

passion and subtlety of her theological imagination, the fecundity of

her

exegetical talents are unevenly displayed here. Yet the person of

Simone Weil

is here as surely as in any of her other books—the person who is

excruciatingly

identical with her ideas, the person who is rightly regarded as one of

the most

uncompromising and troubling witnesses to the modern travail of the

spirit. Co ai "noi nang" chi may bai cua Weil khg vay? Khg biet co ai kien nhan doc? Phúc đáp: Cần gì ai đọc! Tks. Take care. NQT * Bac viet phach loi nhu the nay - ky qua... * Thi phai phach loi nhu vay, gia roi. * Gia roi phai hien ma chet! Đa tạ. Nhưng, phách lối, còn thua xa thầy S: Ta là bọ chét! Phỏng Vấn Steiner Tuy cũng thuộc

băng đảng thực dân [mới, so với cũ, là Tẩy], nhưng

quả là Sontag không đọc ra, chỉ ý này, của

Steiner, trong Bad Friday: Với Weil, những

“tội ác” của chủ nghĩa thực dân có hồi đáp liền tù tì theo kiểu đối

xứng, cả về

tôn giáo và chính trị, với sự thoái hóa ở nơi quê nhà, tức “mẫu quốc”. Nhưng Bắc Kít,

giả như có đọc Weil, thì cũng thua thôi, ngay cả ở những đấng cực tinh

anh, là

vì nửa bộ óc của chúng bị liệt, đây là sự thực hiển nhiên, đừng nghĩ là

Gấu cường

điệu. Chúng làm sao nghĩ chúng cũng chỉ 1 thứ thực dân, khi ăn cướp

Miền Nam, vì

chúng biểu là nhà của chúng, vì cũng vẫn nước Mít, tại làm sao mà nói

là chúng ông

ăn cướp được. Chúng còn nhơ

bẩn hơn cả tụi Tẩy mũi lõ, tụi Yankee mũi lõ. Steiner còn

bài “Thánh Simone-Simone Weil”, trên TV cũng đã giới thiệu. For Weil, the "crimes" of colonialism related immediately, in both religious and political symmetry, to the degradation of the homeland. Time and again, a Weil aphorism, a marginalium to a classical or scriptural passage, cuts to the heart of a dilemma too often masked by cant or taboo. She did not flinch from contradiction, from the insoluble. She believed that contradiction "experienced right to the depths of one's being means spiritual laceration, it means the Cross." Without which "cruciality" theological debates and philosophic postulates are academic gossip. To take seriously, existentially, the question of the significance of human life and death on a bestialized, wasted planet, to inquire into the worth or futility of political action and social design is not merely to risk personal health or the solace of common love: it is to endanger reason itself. The two individuals who have in our time not only taught or written or generated conceptually philosophic summonses of the very first rank but lived them, in pain, in self-punishment, in rejection of their Judaism, are Ludwig Wittgenstein and Simone Weil. At how very many points they walked in the same lit shadows. Đối với Simone Weil, những “tội ác” của chủ nghĩa thực dân thì liền lập tức mắc míu tới băng hoại, thoái hóa, cả về mặt tôn giáo lẫn chính trị ở nơi quê nhà. Nhiều lần, một Weil lập ngôn – những lập ngôn này dù được trích ra từ văn chương cổ điển hay kinh thánh, thì đều như mũi dao - cắt tới tim vấn nạn, thứ thường xuyên che đậy bằng đạo đức giả, cấm kỵ. Bà không chùn bước trước mâu thuẫn, điều không sao giải quyết. Bà tin rằng, mâu thuẫn là ‘kinh nghiệm những khoảng sâu thăm thẳm của kiếp người, và, kiếp người là một cõi xé lòng, và, đây là Thập Giá”. Nếu không ‘rốt ráo’ đến như thế, thì, những cuộc thảo luận thần học, những định đề triết học chỉ là ba trò tầm phào giữa đám khoa bảng. Nghiêm túc mà nói, sống chết mà bàn, câu hỏi về ý nghĩa đời người và cái chết trên hành tinh thú vật hóa, huỷ hoại hoá, đòi hỏi về đáng hay không đáng, một hành động chính trị hay một phác thảo xã hội, những tra vấn đòi hỏi như vậy không chỉ gây rủi ro cho sức khoẻ cá nhân, cho sự khuây khoả của một tình yêu chung, mà nó còn gây họa cho chính cái gọi là lý lẽ.Chỉ có hai người trong thời đại chúng ta, hai người này không chỉ nói, viết, hay đề ra những thảo luận triết học mang tính khái niệm ở đẳng cấp số 1, nhưng đều sống chúng, trong đau đớn, tự trừng phạt chính họ, trong sự từ bỏ niềm tin Do Thái giáo của họ, đó là Ludwig Wittgenstein và Simone Weil. Đó là vì sao, ở rất nhiều điểm, họ cùng bước trong những khoảng tối tù mù như nhau.

Le poète

intraitable Il ne peut

toutefois adhérer au marxisme: la lecture de Simone Weil (qu'il traduit

en

polonais) a joué à cet égard un rôle capital dans son évolution

intellectuelle.

Elle aura été la première à dévoiler la contradiction dans les termes

que

représente le « matérialisme dialectique ». Pour une pensée

intégralement

matérialiste (comme celle d'Engels), l'histoire est le produit de

forces

entièrement étrangères à l'individu, et l'avènement de la société

communiste, une

conséquence logique de l'histoire; la liberté n'y a aucune place. En y

introduisant la « dialectique ", Marx réaffirme que l'action des

individus

est malgré tout nécessaire pour qu'advienne la société idéale: mais

cette

notion amène avec elle l'idéalisme hégélien et contredit à elle seule

le

matélialisme. C'est cette contradiction qui va conduire les sociétés «

socialistes" à tenir l'individu pour quantité négligeable tout en

exigeant

de lui qu'il adhère au sens supposé inéluctable de l'histoire. Mais la

philosophie de Simone Weil apporte plus encore à Milosz que cette

critique:

elle lui livre les clés d'une anthropologie chrétienne qui, prolongeant

Pascal,

décrit l'homme comme écartelé entre la « pesanteur" et la « grâce ". Nhà thơ

không làm sao “xử lý” được. Tuy nhiên,

ông không thể vô Mác Xít: Việc ông đọc Simone Weil [mà ông dịch qua

tiếng Ba

Lan] đã đóng 1 vai trò chủ yếu trong sự tiến hóa trí thức của ông. Bà

là người

đầu tiên vén màn cho thấy sự mâu thuẫn trong những thuật ngữ mà chủ

nghĩa duy vật

biện chứng đề ra. Ðối với một tư tưởng toàn-duy vật [như của Engels],

lịch sử

là sản phẩm của những sức mạnh hoàn toàn xa lạ với 1 cá nhân con người,

và cùng

với sự lên ngôi của xã hội Cộng Sản, một hậu quả hữu lý của lịch sử; tự

do chẳng

hề có chỗ ở trong đó. Khi đưa ra cái từ “biện chứng”, Marx tái khẳng

định hành

động của những cá nhân dù bất cứ thế nào thì đều cần thiết để đi đến xã

hội lý

tưởng: nhưng quan niệm này kéo theo cùng với nó, chủ nghĩa lý tưởng của

Hegel,

và chỉ nội nó đã chửi bố chủ nghĩa duy vật. Chính mâu thuẫn này dẫn tới

sự kiện,

những xã hội “xã hội chủ nghĩa” coi cá nhân như là thành phần chẳng

đáng kể, bọt

bèo của lịch sử, [như thực tế cho thấy], trong khi đòi hỏi ở cá nhân,

phải tất

yếu bọt bèo như thế. Nhưng triết học của Simone Weil đem đến cho Milosz

quá cả

nền phê bình đó: Bà đem đến cho ông những chiếc chìa khoá của một nhân

bản học

Ky Tô, mà, kéo dài Pascal, diễn tả con người như bị chia xé giữa “trọng

lực” và

“ân sủng”. Chúng ta phải

coi cái đẹp như là trung gian giữa cái cần và cái tốt (mediation

between

necessity and the good), giữa trầm trọng và ân sủng (gravity and

grace). Milosz

cố triển khai tư tưởng này [của Weil], trong

tác phẩm “Sự Nắm Bắt Quyền Lực”, tiếp theo

“Cầm Tưởng”. Đây là một

cuốn tiểu thuyết viết hối hả, với ý định cho tham dự một cuộc thi văn

chương,

nghĩa là vì tiền, và cuối cùng đã đoạt giải! Viết hối hả, vậy mà chiếm

giải,

nhưng thật khó mà coi đây là một tuyệt phẩm. Ngay chính tác giả cũng vờ

nó đi,

khi viết Lịch Sử Văn Học Ba Lan. Tuy nhiên, đây là câu chuyện của thế

kỷ. Nhân

vật chính của cuốn tiểu thuyết tìm cách vượt biên giới Nga, để sống

dưới chế độ

Nazi, như Milosz đã từng làm như vậy. THE

IMPORTANCE OF SIMONE WElL FRANCE

offered a rare gift to the contemporary world in the person of Simone

Weil. The

appearance of such a writer in the twentieth century was against all

the rules of

probability, yet improbable things do happen. The life of

Simone Weil was short. Born in 1909 in Paris, she died in England in

1943 at

the age of thirty-four. None of her books appeared during her own

lifetime.

Since the end of the war her scattered articles and her

manuscripts-diaries,

essays-have been published and translated into many languages. Her work

has

found admirers all over the world, yet because of its austerity it

attracts

only a limited number of readers in every country. I hope my

presentation will

be useful to those who have never heard of her. [suite] Czeslaw

Milosz  Trong số báo

về Lòng Từ Thiện, có bài của Simone Weil, trích từ The Need for Roots. Trong tiểu

sử của bà, có trích dẫn một câu, của Susan Sontag, viết về Weil: [From The

Need for Roots]. Born in Paris in 1909, Weil dedicated her lift to

advocating

for the poor and disenfranchised. She worked as a teacher, trained with

an

anarchist unit during the Spanish Civil War, and once debated Leon

Trotsky in

her parents' apartment after arranging for him to hold a clandestine

meeting

there. Weil's uncompromising asceticism led Susan Sontag to declare,

"No

one who loves life would wish to imitate her dedication to martyrdom."

The

bulk of Weil's writing was published only after her death from

tuberculosis in

1943. Gấu không nghĩ là cái tay “viết lại” Kẻ Xa Lạ và được Goncourt năm nay, hiểu được Camus. Tư tưởng của Camus, là từ Weil mà ra, (b) và Weil, như Susan Sontag, viết ở trên, cho rằng, chẳng ai dám bắt chước Weil, nếu kẻ đó còn yêu cuộc đời này! Bất giác lại nhớ tới lời

phẩm bình của vị thân hữu của TV. Vị này giải

thích,

Camus đẹp trai quá, “gái” nhiều quá, làm sao bắt chước cái khổ hạnh ghê

gớm như

của Weil! Có 1 cái gì

cực kỳ ngược ngạo, và hình như lại bổ túc cho nhau, giữa câu của Weil,

khi nhìn

những đoàn quân Nazi tiến vào Paris, và của TTT, khi nhìn VC Bắc Kít vô

Saigon. (b) Violent in

her judgments and uncompromising, Simone Weil was, at least by

temperament, an

Albigensian, a Cathar; this is the key to her thought. She drew extreme

conclusions from the Platonic current in Christianity. Here we touch perhaps

upon hidden ties between her and Albert Camus. The first work

by Camus was his

university dissertation on Saint Augustine. Camus, in my opinion, was

also a

Cathar, a pure one, and if he rejected God it was out of love for God

because

he was not able to justify Him. The last novel written by Camus, The

Fall, is

nothing else but a treatise on Grace-absent grace-though it is also a

satire:

the talkative hero, Jean-Baptiste Clamence, who reverses the words of

Jesus and

instead of "Judge not and ye shall not be judged" gives the advice

"Judge, and ye shall not be judged," could be, I have reasons to

suspect, Jean-Paul Sartre.  Susan Sontag Note: Bài viết

cách đây 50 năm, nhân kỷ niệm 50 năm NYRB, bèn cho đăng lại. Susan

Sontag không

đọc được Simone Weil. Cách nhìn của bà thua cả Gấu, đó là sự thực. Steiner,

Milosz, đọc Simone Weil, "đốn ngộ" hơn nhiều. Trên TV đã dịch bài của

Steiner. Gấu sẽ đi tiếp bài của Milosz, "Sự quan

trọng

của Simone Weil", in trong “To Begin Where I Am”. Trong cuốn này, có

mấy

bài thật là tuyệt. Bài essay, sau đây, chỉ cái tít không thôi, đã chửi

bố mấy đấng

VC đứng về phe nước mắt: Sontag chỉ

chịu nổi cuốn sau đây của Simone Weil:

The

principal value of the collection is simply that anything from Simone

Weil’s

pen is worth reading. It is perhaps not the book to start one’s

acquaintance

with this writer—Waiting for God, I

think, is the best for that. The originality of her psychological

insight, the

passion and subtlety of her theological imagination, the fecundity of

her

exegetical talents are unevenly displayed here. Yet the person of

Simone Weil

is here as surely as in any of her other books—the person who is

excruciatingly

identical with her ideas, the person who is rightly regarded as one of

the most

uncompromising and troubling witnesses to the modern travail of the

spirit. Co ai "noi nang" chi may bai cua Weil khg vay? Khg biet co ai kien nhan doc? Phúc đáp: Cần gì ai đọc! Tks. Take care. NQT * Bac viet phach loi nhu the nay - ky qua... * Thi phai phach loi nhu vay, gia roi. * Gia roi phai hien ma chet! Đa tạ. Nhưng, phách lối, còn thua xa thầy S: Ta là bọ chét! Phỏng Vấn Steiner Tuy cũng thuộc

băng đảng thực dân [mới, so với cũ, là Tẩy], nhưng

quả là Sontag không đọc ra, chỉ ý này, của

Steiner, trong Bad Friday: Với Weil, những

“tội ác” của chủ nghĩa thực dân có hồi đáp liền tù tì theo kiểu đối

xứng, cả về

tôn giáo và chính trị, với sự thoái hóa ở nơi quê nhà, tức “mẫu quốc”. Nhưng Bắc Kít,

giả như có đọc Weil, thì cũng thua thôi, ngay cả ở những đấng cực tinh

anh, là

vì nửa bộ óc của chúng bị liệt, đây là sự thực hiển nhiên, đừng nghĩ là

Gấu cường

điệu. Chúng làm sao nghĩ chúng cũng chỉ 1 thứ thực dân, khi ăn cướp

Miền Nam, vì

chúng biểu là nhà của chúng, vì cũng vẫn nước Mít, tại làm sao mà nói

là chúng ông

ăn cướp được. Chúng còn nhơ

bẩn hơn cả tụi Tẩy mũi lõ, tụi Yankee mũi lõ. Steiner còn

bài “Thánh Simone-Simone Weil”, trên TV cũng đã giới thiệu. For Weil, the "crimes" of colonialism related immediately, in both religious and political symmetry, to the degradation of the homeland. Time and again, a Weil aphorism, a marginalium to a classical or scriptural passage, cuts to the heart of a dilemma too often masked by cant or taboo. She did not flinch from contradiction, from the insoluble. She believed that contradiction "experienced right to the depths of one's being means spiritual laceration, it means the Cross." Without which "cruciality" theological debates and philosophic postulates are academic gossip. To take seriously, existentially, the question of the significance of human life and death on a bestialized, wasted planet, to inquire into the worth or futility of political action and social design is not merely to risk personal health or the solace of common love: it is to endanger reason itself. The two individuals who have in our time not only taught or written or generated conceptually philosophic summonses of the very first rank but lived them, in pain, in self-punishment, in rejection of their Judaism, are Ludwig Wittgenstein and Simone Weil. At how very many points they walked in the same lit shadows. Đối với Simone Weil, những “tội ác” của chủ nghĩa thực dân thì liền lập tức mắc míu tới băng hoại, thoái hóa, cả về mặt tôn giáo lẫn chính trị ở nơi quê nhà. Nhiều lần, một Weil lập ngôn – những lập ngôn này dù được trích ra từ văn chương cổ điển hay kinh thánh, thì đều như mũi dao - cắt tới tim vấn nạn, thứ thường xuyên che đậy bằng đạo đức giả, cấm kỵ. Bà không chùn bước trước mâu thuẫn, điều không sao giải quyết. Bà tin rằng, mâu thuẫn là ‘kinh nghiệm những khoảng sâu thăm thẳm của kiếp người, và, kiếp người là một cõi xé lòng, và, đây là Thập Giá”. Nếu không ‘rốt ráo’ đến như thế, thì, những cuộc thảo luận thần học, những định đề triết học chỉ là ba trò tầm phào giữa đám khoa bảng. Nghiêm túc mà nói, sống chết mà bàn, câu hỏi về ý nghĩa đời người và cái chết trên hành tinh thú vật hóa, huỷ hoại hoá, đòi hỏi về đáng hay không đáng, một hành động chính trị hay một phác thảo xã hội, những tra vấn đòi hỏi như vậy không chỉ gây rủi ro cho sức khoẻ cá nhân, cho sự khuây khoả của một tình yêu chung, mà nó còn gây họa cho chính cái gọi là lý lẽ.Chỉ có hai người trong thời đại chúng ta, hai người này không chỉ nói, viết, hay đề ra những thảo luận triết học mang tính khái niệm ở đẳng cấp số 1, nhưng đều sống chúng, trong đau đớn, tự trừng phạt chính họ, trong sự từ bỏ niềm tin Do Thái giáo của họ, đó là Ludwig Wittgenstein và Simone Weil. Đó là vì sao, ở rất nhiều điểm, họ cùng bước trong những khoảng tối tù mù như nhau.

THE GREAT POET HAS GONE THINKING OF

C.M.

When the

great poet has gone, At noon the

same noise surges, When we part

for a long while Nhà thơ lớn đã

ra đi Nghĩ về C.M. Lẽ dĩ nhiên

chẳng có gì thay đổi Khi nhà thơ

lớn ra đi Tới trưa, vẫn

thứ tiếng ồn đó nổi lên, Hay mãi mãi, xa một người nào đó mà chúng ta yêu Chúng ta bất thình lình cảm thấy đếch kiếm ra lời. Đếch có lời. Chúng ta phải nói cho chúng ta, bây giờ. Đếch có ai làm chuyện này cho chúng ta nữa- Kể từ khi mà nhà thơ lớn đã ra đi TV tính giới

thiệu cùng lúc, nhân dịp VC vinh danh nhà thơ BG, với tác phẩm mới ra

lò “Đười Ươi

Chân Kinh”, ba nhà thơ Ba Lan, qua bài Charles Simic, và bài viết của

Clare Cavanagh

về Milosz, Wiles of Art

vào lúc

cả thế giới đang kỷ niệm lần thứ 100 năm sinh của ông. Đây là

cách đọc song song, nhân đó tìm ra những gì mà thế giới thừa, mà Mít

thì

lại quá

thiếu: Mít làm sao có 1 ông

Brodsky mới 24 tuổi, đã bị lịch sử lọc ra

để đóng

vai đỉnh cao tuyệt vời của thơ Nga. Quả là Chúa cho ông, như

ông viết trong bài viết ngắn: To Wash

At the end

of his life, a poet thinks: I have plunged into so many of the

obsessions and

stupid ideas of my epoch! It would be necessary to put me in a bathtub

and

scrub me still all that dirt was washed away. And yet only because of

that dirt

could I be a poet of the twentieth century, and perhaps the Good Lord

wanted

it, so that I was of use to Him. Thiên đàng là

gì? Nhà thơ Brenda Hillman có lần hỏi Milosz. Và nhà thơ trả lời 1 cách

thật là

quyết định: "If I could at last tell you what is in me, / If I could shout: people! I have lied by pretending it was not there". "Writing has been for me a protective strategy/Of erasing traces" "My life story is one of the most astonishing I have ever come across", Milosz writes in his ABC's (2001; Abecadlo Milosza, 1997-8).

FRUIT How

unattainable life is, it only reveals

Trái Cây

Làm sao mà

tó được cuộc đời

Tưởng Niệm

Czeslaw Milosz [1911-2004] Ông là nhà

thơ của thông minh lớn và tuyệt cảm lớn [a poet of ‘great intelligence

and

great ecstasy’]; thơ của ông sẽ không thể sống sót nếu thiếu hai món

này. Thiếu

thông minh, là sẽ rớt vào trò cãi tay đôi với một trong những đối thủ

này nọ, rồi

cứ thế mà tủn mủn, tàn tạ đi [bởi vì, những con quỉ của thế kỷ 20 này,

chúng

đâu có thiếu khả năng biện chứng, chẳng những thế, chúng còn tự hào về

những

“biện chứng pháp” duy này duy nọ…]. Thiếu tuyệt cảm, làm sao vươn tới

được những ngọn đỉnh trời? Thiếu nó, là sẽ

chỉ suốt đời

làm một anh ký giả tuyệt vời! Ông tự gọi mình là một tay bi quan tuyệt

cảm

[ecstatic pessimist], nhưng chúng ta cũng sẽ vấp vào những hòn đảo nho

nhỏ của

sự tuyệt cảm mà Bergson coi đây là dấu

hiệu khi chạm tới được một sự thực nội tại. Vào thời đại của Beckett, một nhà văn lớn lao, dí dỏm, và cũng rất ư là sầu muộn, Milosz bảo vệ chiều hướng tông giáo của kinh nghiệm của chúng ta, bảo vệ quyền được vuơn tới cõi vô cùng của chúng ta. Bức điện tín của Nietzsche, thông báo cho những con người ở Âu Châu, rằng Thượng Đế đã chết, bức điện đã tới tay Milosz, nhưng ông không từ chối ký nhận, và cứ thế gửi trả cho người gửi.

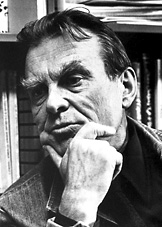

Czeslaw

Milosz The Nobel

Prize in Literature 1980 was awarded to Czeslaw Milosz "who

with uncompromising clear-sightedness voices man's exposed

condition in a world of severe conflicts". Giải Nobel văn

chương 1980 được trao cho Czeslaw Milosz “người mà, bằng cái nhìn rạch

ròi, cương

quyết, không khoan nhượng, gióng lên phận người bày ra đấy, trong một

thế giới

với những mâu thuẫn gay go, khốc liệt”. Một

trong những người được Noebel mà tôi đọc khi còn là 1 đứa con nít đã

ảnh hưởng

đậm lên tôi, tới cả những quan niệm về thơ ca. Ðó là Selma Lagerlöf.

Cuốn sách

thần kỳ của bà, Cuộc phiêu lưu trên

lưng ngỗng mà tôi thật mê, đã đặt

anh cu

Nils vào một vai kép. Anh cu Nils bay trên lưng ngỗng nhìn Trái Ðất như

từ bên

trên, và cùng lúc, trong mọi chi tiết. Cái nhìn kép này có thể là 1 ẩn

dụ về

thiên hướng của nhà thơ. Tôi tìm thấy 1 ẩn dụ tương tự ở trong một ode

La Tinh,

của nhà thơ thế kỷ 17, Maciej Sarbiewski, người được cả Âu Châu biết

dưới bút

hiệu Casimire. Ông dạy thơ ở đại học của tôi. Trong 1 bài ode, ông miêu

tả cuộc

du lịch của mình - ở trên lưng Pegasus, từ Vilno tới Antwerp, thăm bạn

thơ của ông.

Như Nils Holgersson, ông ôm bên dưới ông, sông, hồ, rừng, nghĩa là 1

cái bản đồ,

vừa xa nhưng lại vừa cụ thể. Simone Weil mà tôi mang nợ rất nhiều những bài viết của bà, nói: “Khoảng cách là linh hồn của cái đẹp”. Tuy nhiên, đôi khi giữ được khoảng cách là 1 điều bất khả. Tôi là Ðứa bé của Âu châu, như cái tít của 1 trong những bài thơ của tôi thừa nhận, nhưng đó là 1 thừa nhận cay đắng, mỉa mai. Tôi còn là tác giả của một cuốn sách tự thuật mà bản dịch tiếng Tây có cái tít Một Âu châu khác. Không nghi ngờ chi, có tới hai Âu châu, và chuyện xẩy ra là, chúng tôi, cư dân của một Âu châu thứ nhì, bị số phận ra lệnh, phải lặn xuống “trái tim của bóng đen của Thế Kỷ 20”. Tôi sẽ chẳng biết nói thế nào về thơ ca, tổng quát. Tôi phải nói về thơ ca và cuộc đụng độ, hội ngộ, đối đầu, gặp gỡ… của nó, với một số hoàn cảnh kỳ cục, quái dị, về thời gian và nơi chốn… Czeslaw Milosz Chính là nhờ

đọc đoạn trên đây, mà Gấu “ngộ” ra thời gian đi tù VC của Gấu là quãng

đời đẹp

nhất, và “khoảng cách là linh hồn của cái đẹp”, cái đẹp ở đây là của

những bản

nhạc sến mà Gấu chỉ còn có nó để mang theo vô tù. Trại Tù VC:

Hoàn cảnh kỳ cục, quái dị về thời gian và nơi chốn,

READING

MILOSZ I read your

poetry once more, -Adam

Zagajewski (Translated from the Polish by Clare Cavanagh) The New York

Review, 1 March, 2007. Đọc Milosz

nqt chuyển dịch Bài thơ

trên, khi được in lại trong cuốn The Eternal

Enemies, khác, so với bản tên báo. READING

MllOSZ I read your

poetry once more, You always

wanted to go Sometimes

your tone that poetry-

how to put it? – I lay my book aside, and the city's ordinary din resumes- somebody coughs, someone cries and curses.

Czeslaw

Milosz The Nobel

Prize in Literature 1980 was awarded to Czeslaw Milosz "who

with uncompromising clear-sightedness voices man's exposed

condition in a world of severe conflicts". One of the

Nobel laureates whom I read in childhood influenced to a large extent,

I

believe, my notions of poetry. That was Selma Lagerlöf. Her Wonderful

Adventures of Nils, a book I loved, places the hero in a double role.

He is the

one who flies above the Earth and looks at it from above but at the

same time

sees it in every detail. This double vision may be a metaphor of the

poet's

vocation. I found a similar metaphor in a Latin ode of a

Seventeenth-Century

poet, Maciej Sarbiewski, who was once known all over Europe under the

pen-name

of Casimire. He taught poetics at my university. In that ode he

describes his

voyage - on the back of Pegasus - from Vilno to Antwerp, where he is

going to

visit his poet-friends. Like Nils Holgersson he beholds under him

rivers,

lakes, forests, that is, a map, both distant and yet concrete. Hence,

two

attributes of the poet: avidity of the eye and the desire to describe

that

which he sees. Yet, whoever considers poetry as "to see and to

describe" should be aware that he engages in a quarrel with modernity,

fascinated as it is with innumerable theories of a specific poetic

language.

Simone Weil,

to whose writings I am profoundly indebted, says: "Distance is the soul

of

beauty." Yet sometimes keeping distance is nearly impossible. I am A

Child

of Europe, as the title of one of the my poems admits, but that is a

bitter,

sarcastic admission. I am also the author of an autobiographical book

which in

the French translation bears the title Une autre Le poète

intraitable Il ne peut toutefois adhérer au marxisme: la lecture de Simone Weil (qu'il traduit en polonais) a joué à cet égard un rôle capital dans son évolution intellectuelle. Elle aura été la première à dévoiler la contradiction dans les termes que représente le « matérialisme dialectique ». Pour une pensée intégralement matérialiste (comme celle d'Engels), l'histoire est le produit de forces entièrement étrangères à l'individu, et l'avènement de la société communiste, une conséquence logique de l'histoire; la liberté n'y a aucune place. En y introduisant la « dialectique ", Marx réaffirme que l'action des individus est malgré tout nécessaire pour qu'advienne la société idéale: mais cette notion amène avec elle l'idéalisme hégélien et contredit à elle seule le matélialisme. C'est cette contradiction qui va conduire les sociétés « socialistes" à tenir l'individu pour quantité négligeable tout en exigeant de lui qu'il adhère au sens supposé inéluctable de l'histoire. Mais la philosophie de Simone Weil apporte plus encore à Milosz que cette critique: elle lui livre les clés d'une anthropologie chrétienne qui, prolongeant Pascal, décrit l'homme comme écartelé entre la « pesanteur" et la « grâce ". Nhà thơ không

làm sao “xử lý” được. Tuy nhiên, ông không thể vô Mác Xít: Việc ông đọc Simone Weil [mà ông dịch qua tiếng Ba Lan] đã đóng 1 vai trò chủ yếu trong sự tiến hóa trí thức của ông. Bà là người đầu tiên vén màn cho thấy sự mâu thuẫn trong những thuật ngữ mà chủ nghĩa duy vật biện chứng đề ra. Ðối với một tư tưởng toàn-duy vật [như của Engels], lịch sử là sản phẩm của những sức mạnh hoàn toàn xa lạ với 1 cá nhân con người, và cùng với sự lên ngôi của xã hội Cộng Sản, một hậu quả hữu lý của lịch sử; tự do chẳng hề có chỗ ở trong đó. Khi đưa ra cái từ “biện chứng”, Marx tái khẳng định hành động của những cá nhân dù bất cứ thế nào thì đều cần thiết để đi đến xã hội lý tưởng: nhưng quan niệm này kéo theo cùng với nó, chủ nghĩa lý tưởng của Hegel, và chỉ nội nó đã chửi bố chủ nghĩa duy vật. Chính mâu thuẫn này dẫn tới sự kiện, những xã hội “xã hội chủ nghĩa” coi cá nhân như là thành phần chẳng đáng kể, bọt bèo của lịch sử, [như thực tế cho thấy], trong khi đòi hỏi ở cá nhân, phải tất yếu bọt bèo như thế. Nhưng triết học của Simone Weil đem đến cho Milosz quá cả nền phê bình đó: Bà đem đến cho ông những chiếc chìa khoá của một nhân bản học Ky Tô, mà, kéo dài Pascal, diễn tả con người như bị chia xé giữa “trọng lực” và “ân sủng”. Chúng ta phải

coi cái đẹp như là trung gian giữa cái cần và cái tốt (mediation

between

necessity and the good), giữa trầm trọng và ân sủng (gravity and

grace). Milosz

cố triển khai tư tưởng này [của Weil], trong

tác phẩm “Sự Nắm Bắt Quyền Lực”, tiếp theo

“Cầm Tưởng”. Đây là một

cuốn tiểu thuyết viết hối hả, với ý định cho tham dự một cuộc thi văn

chương,

nghĩa là vì tiền, và cuối cùng đã đoạt giải! Viết hối hả, vậy mà chiếm

giải,

nhưng thật khó mà coi đây là một tuyệt phẩm. Ngay chính tác giả cũng vờ

nó đi,

khi viết Lịch Sử Văn Học Ba Lan. Tuy nhiên, đây là câu chuyện của thế

kỷ. Nhân

vật chính của cuốn tiểu thuyết tìm cách vượt biên giới Nga, để sống

dưới chế độ

Nazi, như Milosz đã từng làm như vậy. Ða số những tác giả TV giới thiệu, thì đều là từ cái lò Partisan Review. Và đều kinh qua kinh nghiệm CS, như Milosz, như Manea, thí dụ. Gấu

biết tờ này, là do đọc Paz. Nhưng

phải đến khi ra được hải ngoại, được đọc Simone Weil, đọc Milosz, đọc

Manea, đọc

Brodsky, Coetzee… thì mới tới chỉ!

Tởm Người ta đã

nói nhiều về những tội ác của chế độ cộng sản. Ít ai cho biết, tôi đã

tởm chế độ

đó đến mức như thế nào. Câu chuyện sau đây là của nhà văn, nhà thơ lưu

vong người

Balan, Czeslaw Milosz, Nobel văn chương 1980, trong tác phẩm Milosz's

ABC's. Disgust Józef

Czapski là người kể cho tôi [Milosz] câu chuyện sau đây, xẩy ra trong

thời kỳ

Cách Mạng Nga. Bất thình lình, ông tàn dư bèn đứng dậy, rút khẩu súng lục từ trong túi ra, và đưa ngay mõm súng vào trong mõm mình, và đoàng một phát. Hiển nhiên, mức tởm lợm

tràn quá ly. Chẳng nghi ngờ chi, ông ta là một thứ

người mảnh

mai, được giáo dục, dậy dỗ, và trưởng thành trong một môi trường mà một

con người

như thế dư sức sống, và sống thật là đầy đủ cái phần đời của mình mà

Thượng Đế

cho phép, nghĩa là được bảo vệ để tránh xa khỏi thực tại tàn bạo được

tầng lớp

hạ lưu chấp nhận như là lẽ đương nhiên ở đời. Nếu không, Thượng Đế đâu

có đẩy

ông ta vào thế gian này? Milosz, khi

viết về Brodsky, không thèm giấu giếm nỗi ghen tị của ông, thằng chả

sao sướng

thế, chẳng bao giờ phải chịu nhục, chịu bửn, dù chỉ 1 tí, như ta! Ông viết To wash

là cũng theo tinh thần đó, tớ là nhà thơ bửn của thế kỷ. Ðọc Milosz

viết về Brodsky, chúng ta hiểu thái độ "kênh kiệu ", "không

khiêm tốn" của TTT. To

At the end of his life, a poet thinks: I have plunged into so many of the obsessions and stupid ideas of my epoch! It would be necessary to put me in a bathtub and scrub me still all that dirt was washed away. And yet only because of that dirt could I be a poet of the twentieth century, and perhaps the Good Lord wanted it, so that I was of use to Him. Một nhà thơ của thế kỷ 20,

cuối đời nhìn lại, thấy mình bẩn quá, bèn chui vô bồn

tắm, dùng xà bông thơm kỳ cọ, cho văng tất cả những cái bẩn đi. Notes About Brodsky Trong một tiểu luận, Brodsky

gọi Mandelstam là một thi sĩ của văn

hóa. Brodsky chính ông, cũng là 1 thi sĩ của văn hóa, và hẳn là vì lý

do này,

ông tạo sự hài hòa với dòng sâu thẳm của thế kỷ, trong đó con người, bị

đe dọa

mất mẹ cái giống người, khám phá ra quá khứ như là một mê cung chẳng hề

có tận

cùng. Lặn sâu vô mê cung, chúng ta khám phá ra cái gì sống sót quá khứ

là kết

quả của nguyên lý phân biệt dựa trên đẳng cấp. Mandelstam, ở trong

Gulag, điên

khùng bới đống rác tìm đồ ăn, [ui chao lại nhớ Giàng Búi], là thực tại

về độc

tài bạo chúa và sự băng hoại thoái hoá bị kết án phải tuyệt diệt.

Mandelstam

đọc thơ cho vài bạn tù là khoảnh khoắc thần tiên còn hoài hoài Bài viết Sự quan trọng của

Simone Weil cũng quá tuyệt. Bắc Kít, chỉ có thứ nhà văn nhà

thơ viết dưới ánh sáng của Đảng! Cái vụ Tố Hữu khóc Stalin thảm

thiết, phải mãi gần đây Gấu mới

giải ra được, sau khi đọc một số bài viết của những Hoàng Cầm, Trần

Dần, những

tự thú, tự kiểm, sổ ghi sổ ghiếc, hồi ký Nguyễn Đăng Mạnh... Sự hèn

nhát của sĩ

phu Bắc Hà, không phải là trước Đảng, mà là trước cá nhân Tố Hữu. Cả xứ

Bắc Kít

bao nhiêu đời Tổng Bí Thư không có một tay nào như xứng với Xì Ta Lin.

Mà, Xì,

như chúng ta biết, suốt đời mê văn chương, nhưng không có tài, tài văn

cũng

không, mà tài phê bình như Thầy Cuốc, lại càng không, nên đành đóng vai

ngự sử

văn đàn, ban phán giải thưởng, ra ơn mưa móc đối với đám nhà văn, nhà

thơ. Ngay

cả cái sự thù ghét của ông, đối với những thiên tài văn học Nga như

Osip

Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova… bây giờ Gấu cũng giải ra được, chỉ là vì

những

người này dám đối đầu với Stalin, không hề chịu khuất phục, hay "vấp

ngã"!  Czeslaw

Milosz Le poète

intraitable Alors qu'on

célèbre le centenaire de la naissance du Prix Nobel polonais, retour

sur un

parcours et une œuvre trop souvent réduite à La Pensée captive, son

essai

magistral sur le totalitarisme. Par

Jean-Yves Masson En août 1980,

quand les ouvriers de Gdansk regroupés autour de ce qui allait devenir

le

syndicat Solidarnosc se mirent en grève, leur première victoire sur le

pouvoir

officiel fut d'obtenir l'édification, sur les chantiers navals, d'un

monument à

la mémoire des victimes de la sanglante répression des grèves de 1970.

Lech

Walesa et ses amis choisirent de faire graver au pied de ce monument

les vers

d'un poète alors interdit de publication en Pologne et exilé aux

États-Unis: «

Toi qui as lésé l'homme simple,/ Éclatant de rire devant sa

détresse,/T'

entourant d'une cour de bouffons,/Pour la confusion du bien et du

mal,/[ ... ] Ne

te crois pas en sécurité. Le poète se souvient/Tu peux le tuer - un

autre poète

naîtra/Seront inscrits les actes et les paroles. » Quelques mois plus

tard, le

prix Nobel de littérature

révélait au monde entier le nom de Czeslaw Milosz, le plus grand poète

polonais

de sa génération et l'un des plus grands de toute l'histoire de la

Pologne. En France,

où il avait demandé l'asile politique dès 1951, on l'avait un peu

oublié depuis

son départ, en 1960, pour les États-Unis: en faisant publier chez

Gallimard en

1953 son essai La Pensée captive,

puis, aussitôt après, un roman politique intitulé La Prise

du pouvoir, Albert Camus l'avait fait connaître au public,

mais comme penseur et polémiste, analyste impitoyable du totalitarisme,

dont

les lecteurs français ne pouvaient se douter qu'il était avant tout un

poète.

Professeur de littérature à Berkeley jusqu'en 1978, connu pour ses

essais

critiques assez tôt traduits en anglais, il aura attendu ce rendez-vous

de l'histoire

que représenta le soulèvement des Polonais contre le joug soviétique

pour être

reconnu comme un poète sur la scène internationale, alors même que ses

vers

interdits circulaient en Pologne sous le manteau depuis longtemps.

Jusqu'à sa

mort, survenue le 14 août 2004, il fut regardé comme une sorte

d'incarnation

vivante de l'âme polonaise, ce qui ne l'empêchait nullement, en

farouche adversaire

du nationalisme qu'il avait toujours été, d'exercer sa vigilance

critique à

l'égard de son pays revenu à la démocratie. Vieille lignée aristocrate

et

lituanienne

La vie de

Czeslaw Milosz est tissée de paradoxes. Premier d'entre eux: bien que

de langue

maternelle polonaise, il n'est pas à proprement parler polonais, mais

lituanien; lui-même avouait avoir ignoré la réalité concrète de la

Pologne

jusqu'à son installation à Varsovie en 1937. Il est né le 30 juin 1911

à

Szetejnie en Lituanie, dans le district majoritairement polonophone de

Kiejdany. La grande ville toute proche est Wilno, alors elle aussi pour

moitié

polonaise (elle ne s'appelle pas encore Vilnius). Il y fera toutes ses

études.

Le lituanien, du groupe finno-ougrien (sans aucun rapport avec les

langues

slaves), est alors une langue surtout paysanne, parlée plus qu'écrite;

le russe

et le polonais sont les langues de culture. Milosz descend d'une

vieille famille

aristocratique, mais lui-même a souvent souligné combien, en faisant le

choix

de devenir ingénieur, son père, Aleksander Milosz, avait coupé les

ponts avec

cette origine. Il n'en a jamais connu l'aisance et n'en a pas eu

l'éducation. Sur les bords de l'issa, traduit en

français en 1956 -le seul de ses romans que Milosz acceptait de

considérer

comme faisant pleinement partie de son œuvre -, est en grande partie

composé

des souvenirs d'une enfance au çontact d'un monde rural où les

traditions

chrétiennes ne sont qu'un vernis sous lequel subsiste l'esprit intact

du paganisme.

Le poète y raconte comment l'innocence première est tôt contredite par

l'expérience

cruciale de la culpabilité: Milosz est en effet profondément marqué par

l'expérience du mal, interprétée à la lumière d'un christianisme qui

n'aura

jamais été pour lui une foi tranquille, mais d'abord une grille de

lecture de

la condition humaine. La nature,

qui est au cœur de ce roman, est la grande source d'inspiration de

toute son

œuvre; adolescent, il se rêve d'ailleurs entomologiste ou botaniste. En

attendant, au lycée, la révolte le gagne: le bon élève se change en

contestataire

qui refuse l'esprit dogmatique du catholicisme (cette révolte sera

encore

sennsible jusque dans son tardif Traité

de théologie, cycle de poèmes écrit à plus de 90 ans). Sa

sensibilité aux

injustices sociales le rapproche alors des grands thèmes de gauche,

sans qu'il

ait jamais été un marxiste orthodoxe. À l'université de Wilno, il

étudie le

droit. Ses premiers poèmes paraissent dans des revues étudiantes; il

fait

partie d'un cercle de jeunes poètes, le Zagary. Un voyage à Paris lui

permet de

faire la connaissance en 1931 d'un parent éloigné, le grand poète Oscar

Vladislas de Lubicz-Milosz, qui signe O. V de I. Milosz, vient de

prendre la

nationalité française et publie exclusivement en français: c'est

surrtout en

1934-1935, lors de son premier grand séjour à Paris, qu'il subira son

influence

au point de pouvoir plus tard se dire, en partie, son disciple, sans

adhérer entièrement

à ses croyances ésotériques. [occultisme en tant que tel, qu'il

découvre

notamment à la lecture de William Blake (l'une de ses grandes

références poétiques)

ou de Swedenborg, restera pour lui une curiosité, un objet qui le

fascine mais

qu'il tient à distance. Les cours de théologie qu'il suit à Paris à

l'Institut

catholique l'intéressent davantage. Il y découvre des outils pour

formuler la

question centrale de toute son œuvre: d'où vient le mal? [histoire des

différentes « hérésies » le fascine, tant il lui semble que l'intuition

chrétienne ne se laisse pas réduire aux dogmes de telle ou telle

confession.

C'est le même refus du dogmatisme qui l'éloignera du marxisme. Le séjour en

France a confirmé Milosz (revenu dans son pays, il travaille à la radio

polonaise) dans sa conviction fondamentale que la Pologne est

d'esssence

profondément européenne; le titre d'un de ses recueils d'après guerre, Enfant d'Europe, le proclamera. Il faut

songer qu'au moment de sa naissance la Pologne, partagée depuis 1848

entre la

Russie, l'Allemagne et l'empire d'Autriche, était encore radiée de la

carte. La

reconstitution d'une Pologne indépendante, conséquence de la guerre de

1914-1918, fut un quasi-miracle que beaucoup de Polonais n'avaient osé

espérer.

Ce qui fait de Milosz bien autre chose encore qu'un grand poète, c'est

que, né

hors de Pologne (comme avant lui Adam Micckiewicz), il la porte en lui

comme

une patrie intérieure constituée avant tout par la langue. Quand, au

terme de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, la Pologne perd de nouveau son

indépendance et passe sous le joug de l'URSS, Milosz, qui a pris part à

la

Résistance contre l'Allemagne par ses poèmes diffusés clandestinement

et par

ses traductions (notamment celle du pamphlet de Jacques Maritain, À travers le désastre), va d'abord

accepter de servir le régime communiste: il entre dans la diplomatie. Il ne peut

toutefois adhérer au marxisme: la lecture de Simone Weil (qu'il traduit

en

polonais) a joué à cet égard un rôle capital dans son évolution

intellectuelle.

Elle aura été la première à dévoiler la contradiction dans les termes

que représente

le « matérialisme dialectique ». Pour une pensée intégralement

matérialiste

(comme celle d'Engels), l'histoire est le produit de forces entièrement

étrangères à l'individu, et l'avènement de la société communiste, une

conséquence logique de l'histoire; la liberté n'y a aucune place. En y

introduisant

la « dialectique ", Marx réaffirme que l'action des individus est

malgré

tout nécessaire pour qu'advienne la société idéale: mais cette notion

amène

avec elle l'idéalisme hégélien et contredit à elle seule le

matélialisme. C'est

cette contradiction qui va conduire les sociétés « socialistes" à tenir

l'individu pour quantité négligeable tout en exigeant de lui qu'il

adhère au

sens supposé inéluctable de l'histoire. Mais la philosoophie de Simone

Weil

apporte plus encore à Milosz que cette critique: elle lui livre les

clés d'une

anthropologie chrétienne qui, prolongeant Pascal, décrit l'homme comme

écartelé

entre la « pesanteur" et la « grâce ". Chanter l'innocence sans y

avoir

droit Le 1er

février 1951, Milosz rompt avec le régime polonais et demande l'asile

politique

à la France. Ses poèmes, pourtant déjà très connus en Pologne, sortent

des

anthologies officielles. Il publiera désormais en exil, surtout grâce

au

mensuel Kultura, édité à Paris de

1947 à 2000 par Jerzy Giedroyc, et à la maison d'édition du même nom.

En 1960,

il part enseigner en Californie, à Berkeley, où un poste de professeur

lui

proocure la liberté nécessaire à la création. Il en résultera, outre

les

poèmes, de nombreux recueils d'essais pour la plupart traduits en

français (Visions de la baie de San Francisco, La

Terre d'Ulm, L'Immortalité de l'art,

Empereur de la terre ... ), où Milosz se révèle l'un des

commentateurs les

plus aigus des auteurs qu'il admire (de Blake à Dante ou Mickiewicz),

mais

aussi un observateur impitoyable de la modernité occidentale: car, s'il

a fui

le communisme, il n'a aucune sympathie pour le libéralisme qui règne en

Occident. Sa vigilance à cet égard n'est pas celle d'un «

intellectuel",

mais ce d'un poète et d'un chrétien. En 1981,

invité à occuper la chaire de poétique Eliot Norton à Harvard, il

prononce six

conférenc publiées sous le titre Témoignage

de la poésie. Traduites en français en 1987, elles sont peut-être

la

meilleure introduction à son œuvre (avec le recueil d'entretiens

intitulé Milosz par Milosz, paru

l'année précédente). Pour Milosz, si la vocation du

poète es d'être un témoin, elle exige aussi qu'il donne à son

témoignage une forme sans laquelle l'entreprise es

vouée à l'échec. Or cette forme implique qu'il prenne par rapport à

l'événement

une distance qui a nécessairement, surtout s'agissant de l'horreur

totalitaire,

quelque chose d'immoral. Il y a donc une culpabilité de l'art, que

seule est

capable de conjurer la conscience que le poète ou l'artiste ont du

péril auquel

ils s'exposent. Le poète n'a pas droit lui-même à l'innocence, et,

comme chez

Blake, il ne peut défendre l'innocence que s'il est capable de se

fonder aussi

sur l'expérience. Ce n'est pas pour rien que le recueil dans lequel

Milosz s'en

prend avec virulence au réalisme socialiste, en 1948, s'intitule Traité moral. Celui-ci est lui-même

inséparable du Traité poétique de 1957. Milosz ne se situe décidément

pas «

par-delà bien et mal ", mais s'interroge avec inquiétude sur sa

responsaabilité de poète et d'homme oscillant entre l'un et

l'autre. Jusqu'à sa mort en 2004, Milosz considéra que le grand danger

de la

modernité résidait dans un retour inaperçu au manichéisme: il voyait

dans une

bonne parrtie de l'art moderne un refus de la matière, un désir

d'échapper au

temps, à la mort et même à l'histoire. Or, pour lui, être poète

signifiait

rappeler inlassablement que nous n'avons pas le droit d'oublier que

nous sommes

pétris de matière et de temps. Symétriqueement, le recours à

l'imaginaire était

pour lui nécessaire afin que nous nous souvenions que nous ne sommes

pas

seulement matière, mais aussi liberté créatrice. Toute sa poésie est

vouée à

tenir ensemble les deux postulations. Ainsi, Czeslaw Milosz n'est pas

seulement

l'un des plus grands poètes d'une Pologne qui, au xxe siècle, en a

compté bien

d'autres encore: il est une figure exemplaire de la conscience

européenne, et

un maître spirituel inépuisable. Le Magazine

Littéraire Octobre 2011 L’année

Milosz en France Dans le

sillage du Ile Festival Czeslaw Milosz [qui a réuni en mai dernier plus

de deux

cents invités à Cracoviel], les instituts polonais à travers le monde

rendent

hommage au poète, cent ans après sa naissance. www.institutpolonais.fr/ Czeslaw

Milosz In Honor of Reverend Baka translated

from the Polish by Anthony Milosz

With permission from Ecco

Press, an imprint of

HarperCollins Publishers. Selected and Last Poems 1931-2004 by

Czeslaw

Milosz is forthcoming as a paperback edition from Ecco Press (November

15,

2011). Czeslaw Milosz was born in

Szetejnie, Lithuania, in 1911. He

worked with the Polish Resistance movement in Warsaw during World War

II, after

which he was stationed in Paris as a cultural attaché from Poland. He

defected

to France in 1951, and in 1960 he accepted a position at the University

of

California at Berkeley. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature

in 1980,

and was a member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and

Letters. He

died in 2004. Anthony Milosz is Czeslaw

Milosz's son. The translations exceprted

here are of his father's last poems before his death; they have never

before

appeared in English and are included in a revised and updated edition, Selected

and Last Poems 1931-2004 by Czeslaw Milosz, forthcoming from Ecco

Press.

|