Album | Thơ | Tưởng Niệm | Nội cỏ của thiên đường | Passage Eden | Sáng tác | Sách mới xuất bản | Chuyện văn

Dịch thuật | Dịch ngắn | Đọc sách | Độc giả sáng tác | Giới thiệu | Góc Sài gòn | Góc Hà nội | Góc Thảo Trường

Lý thuyết phê bình |

Tác giả Việt | Tác giả ngoại | Tác giả & Tác phẩm | Tạp ghi | Text Scan | Tin văn vắn | Thời sự | Thư tín | Phỏng vấn | Phỏng vấn dởm | Phỏng vấn ngắnDịch thuật | Dịch ngắn | Đọc sách | Độc giả sáng tác | Giới thiệu | Góc Sài gòn | Góc Hà nội | Góc Thảo Trường

Giai thoại | Potin | Linh tinh | Thống kê | Viết ngắn | Tiểu thuyết | Lướt Tin Văn Cũ | Kỷ niệm | Thời Sự Hình | Gọi Người Đã Chết

Thơ Mỗi Ngày | Chân Dung | Jennifer Video

Nhật Ký Tin Văn / Viết mỗi ngày/Sách & Báo Mới

https://www.facebook.com/quoc.t.nguyen.1

|

|

Imre Kertész obituary

1929-2016 http://www.tanvien.net/cn/Trang_Kertesz.html Và

sự phục sinh không dứt của sự thiện, chứ không phải của sự

dữ và độc ác, cho chúng ta thấy chân lý

về thế giới và cuộc đời của chúng ta. Nhà văn Do Thái-Hungari,

Imre Kertesz, đã đoạt giải Nobel Văn học năm 2002, đã có

một chứng tá thâm thúy về điều này. Ông

từng là một cậu bé trong trại giết người của Đức Quốc xã,

nhưng điều ông nhớ nhất về quãng thời gian này, không

phải là những bất công, tàn ác, và

cái chết mà ông chứng kiến ở đó, nhưng là

những hành động nhân ái, trìu mến và

vị tha giữa sự dữ. Vì thế sau chiến tranh, ông mong muốn đọc

hạnh các thánh hơn là tiểu sử các tội phạm

chiến tranh. Vẻ ngoài của sự thiện lôi cuốn ông. Với

ông, có thể hiểu được sự dữ, còn sự thiện thì

sao? Ai có thể giải thích được? Nguồn cội sự thiện là

gì? Tại sao sự thiện cứ tuôn ra, tuôn tràn trở

lại trên khắp cõi trái đất, trong mọi tình trạng

thế nào chăng nữa?

http://ronrolheiser.com/the-triumph-of-goodness/#.Vv8aYjZzY5s And it is this, the constant resurrection of goodness, not that of viciousness and evil, which speaks the deepest truth about our world and our lives. The Jewish-Hungarian writer, Imre Kertesz, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2002, gives a poignant testimony of this. He had as a young boy been in a Nazi death camp, but what he remembered most afterwards from this experience was not the injustice, cruelty, and death that he saw there, but rather some acts of goodness, kindness, and altruism he witnessed amidst that evil. After the war, it left him wanting to read the lives of saints rather than biographies of war. The appearance of goodness fascinated him. To his mind, evil is explicable, but goodness? Who can explain it? What is its source? Why does it spring up over and over again all over the earth, and in every kind of situation? It springs up everywhere because God’s goodness and power lie at the source of all being and life. This is what is revealed in the resurrection of Jesus. What the resurrection reveals is that the ultimate source of all that is, of all being and life, is gracious, good, and loving. Moreover it also reveals that graciousness, goodness, and love are the ultimate power inside reality. They will have the final word and they will never be captured, derailed, killed, or ultimately ignored. They will break through, ceaselessly, forever. In the end, too, as Imre Kertesz suggests, they are more fascinating than evil. The Triumph of Goodness March 28, 2016 The stone which rolled away from the tomb of Jesus continues to roll away from every sort of grave. Goodness cannot be held, captured, or put to death. It evades its pursuers, escapes capture, slips away, hides out, even leaves the churches sometimes, but forever rises, again and again, all over the world. Such is the meaning of the resurrection. Goodness cannot be captured or killed. We see this already in the earthly life of Jesus. There are a number of passages in the Gospels which give the impression that Jesus was somehow highly elusive and difficult to capture. It seems that until Jesus consents to his own capture, nobody can lay a hand on him. We see this played out a number of times: Early on in his ministry, when his own townsfolk get upset with his message and lead him to the brow of a hill to hurl him to his death, we are told that “he slipped through the crowd and went away.” Later when the authorities try to arrest him we are told simply that “he slipped away”. And, in yet another incident when he is in temple area and they try to arrest him, the text simply says that he left the temple area and “no one laid a hand upon him because his hour had not yet come.” Why the inability to take him captive? Was Jesus so physically adept and elusive that no one could imprison him? These stories of his “slipping away” are highly symbolic. The lesson is not that Jesus was physically deft and elusive, but rather that the word of God, the grace of God, the goodness of God, and power of God can never be captured, held captive, or ultimately killed. They are adept. They can never be held captive, can never be killed, and even when seemingly they are killed, the stone that entombs them always eventually rolls back and releases them. Goodness continues to resurrect from every sort of grave. And it is this, the constant resurrection of goodness, not that of viciousness and evil, which speaks the deepest truth about our world and our lives. The Jewish-Hungarian writer, Imre Kertesz, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2002, gives a poignant testimony of this. He had as a young boy been in a Nazi death camp, but what he remembered most afterwards from this experience was not the injustice, cruelty, and death that he saw there, but rather some acts of goodness, kindness, and altruism he witnessed amidst that evil. After the war, it left him wanting to read the lives of saints rather than biographies of war. The appearance of goodness fascinated him. To his mind, evil is explicable, but goodness? Who can explain it? What is its source? Why does it spring up over and over again all over the earth, and in every kind of situation? It springs up everywhere because God’s goodness and power lie at the source of all being and life. This is what is revealed in the resurrection of Jesus. What the resurrection reveals is that the ultimate source of all that is, of all being and life, is gracious, good, and loving. Moreover it also reveals that graciousness, goodness, and love are the ultimate power inside reality. They will have the final word and they will never be captured, derailed, killed, or ultimately ignored. They will break through, ceaselessly, forever. In the end, too, as Imre Kertesz suggests, they are more fascinating than evil. And so we are in safe hands. No matter how bad the news on a given day, no matter how threatened our lives are on a given day, no matter how intimidating the neighborhood or global bully, not matter how unjust and cruel a situation, and no matter how omnipotent are anger and hatred, love and goodness will reappear and ultimately triumph. Jesus taught that the source of all life and being is benign and loving. He promised too that our end will be benign and loving. In the resurrection of Jesus, God showed that God has the power to deliver on that promise. Goodness and love will triumph! The ending of our story, both that of our world and that of our individual lives, is already written – and it is a happy ending! We are already saved. Goodness is guaranteed. Kindness will meet us. We only need to live in the face of that wonderful truth. They couldn’t arrest Jesus, until he himself allowed it. They put his dead body in a tomb and sealed it with a stone, but the stone rolled away. His disciples abandoned him in his trials, but they eventually returned more committed than ever. They persecuted and killed his first disciples, but that only served to spread his message. The churches have been unfaithful sometimes, but God just slipped away from those particular temple precincts. God has been declared dead countless time, but yet a billion people just celebrated Easter. Goodness cannot be killed. Believe it! Tks. NQT Trong bài ai điếu trên Guardian, viết: Tác phẩm của K. đôi khi ló ra cái hàm hồ của ông, về tín ngưỡng, khiến đôi khi ông không tin có Thượng Đế. Trong tác phẩm Gályanapló, ông đi 1 đường nghịch thiên, ngược ngạo: Thượng Đế có ở Lò Thiêu. Người ném tôi vô đó, để kể (“bao giờ thì tôi có thể “lại viết”, của TTT, là ở chỗ này) lại cho Người nghe, Người đã làm gì ở đó! Kertész’s books also sometimes betrayed his ambivalent relationship with religion, which at times led him to doubt the existence of God. In his work Gályanapló (Galley Boat-Log, 1992) he chose a paradox to express his doubts: “God is Auschwitz, but also He who brought me out of there, who obliged, even compelled me to give an account of all that there happened, because He wants to know and hear what he had done.” Often tempted by suicide, Kertész somehow persevered and it was not until 2003 in his novel Felszámolás (Liquidation, 2003) that he produced a hero who actually kills himself. The ending to that book was probably influenced by his recurring depression after he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. In 2014, having lived in Berlin for a number of years, Kertész moved back to Budapest, ostensibly for medical treatment.

TCDT: "Lịch sử và chính thống", Văn Học 134, Tháng 6, 1967 Cái này mà đem về trong nước in ư? Một

trong số những

nhà văn có tầm nhìn sáng suốt, về xứ Mít

và cuộc chiến của nó, là Solzhenitsyn. Ngay từ

1975, khi trả lời trong 1 chương trình văn học trên TV Tẩy,

ông đã tiên đoán Miền Bắc sẽ cướp đoạt Miền

Nam, và đây là 1 cuộc chiến tranh chấp quyền lực

giữa các đế quốc, khác hẳn mọi người, trong có Octavio

Paz, khi ông này cho rằng đây là cuộc chiến

giải phóng dân tộc.

Nói rõ hơn, Solzhenitsyn biết chuyện Bắc Kít dâng vợ con đất nước cho Tẫu, để lấy viện trợ, để lấy cho bằng được Miền Nam. Bắc Kít phải hiểu rõ điều này hơn ai hết. Chúng vờ, làm như không biết. Đây là nỗi nhục của cả xứ Bắc Kít, theo cái kiểu mà Sebald nói, về nước Đức, khi họ vờ những trận mưa bom của Đồng Minh lên đất nước, thành phố của họ. Nhạc sĩ Tô Hải hình như cũng có kể về 1 lần gặp gỡ hai tên, 1 VC, áp giải 1 anh tù Ngụy, và để ý, anh VC trang bị, từ đầu đến chim, toàn đồ Tầu,anh Ngụy toàn đồ Mẽo. Cái chuyện Miền Nam được Mẽo lo cho đủ thứ, thì ai cũng biết. Khốn nạn nhất, là khi chúng bỏ mặc Miền Nam cho VC. Chúng cắt mọi viện trợ, làm sao đánh đấm? Chúng bức tử Miền Nam. (1) Trong bài viết "Gulag", trong “On Poets and Others”, Paz chỉnh Solz, khi phán, cuộc chiến Đông Dương là mâu thuẫn quyền lợi giữa đám đế quốc, the war in Indochina was an imperial conflict. Paz coi đây là cuộc chiến giành độc lập của 1 xứ cựu thuộc địa của Pháp. Cái bước ngoặt lịch sử - bốn ngàn năm thù Tẫu của xứ Mít - chấm dứt, xẩy ra đúng vào lúc ông Hồ trốn thoát cuộc canh chừng của Cớm Tẩy ở Paris, và chuồn được qua Moscow. Sau đó, ông thoát cuộc thanh trừng của Xì, và được Xì cho về Trung Quốc, như 1 tên Cớm CS Quốc Tế, ăn lương Cẩm Linh, làm việc với CS Tẫu.

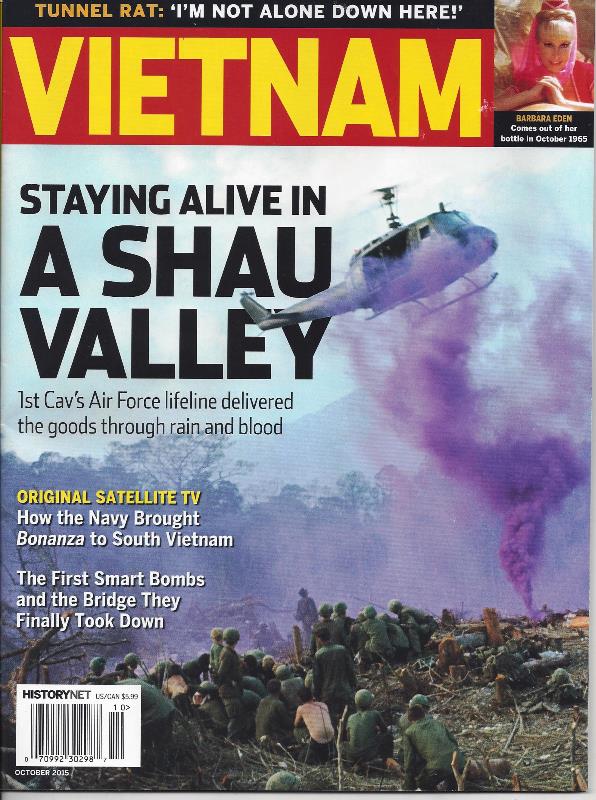

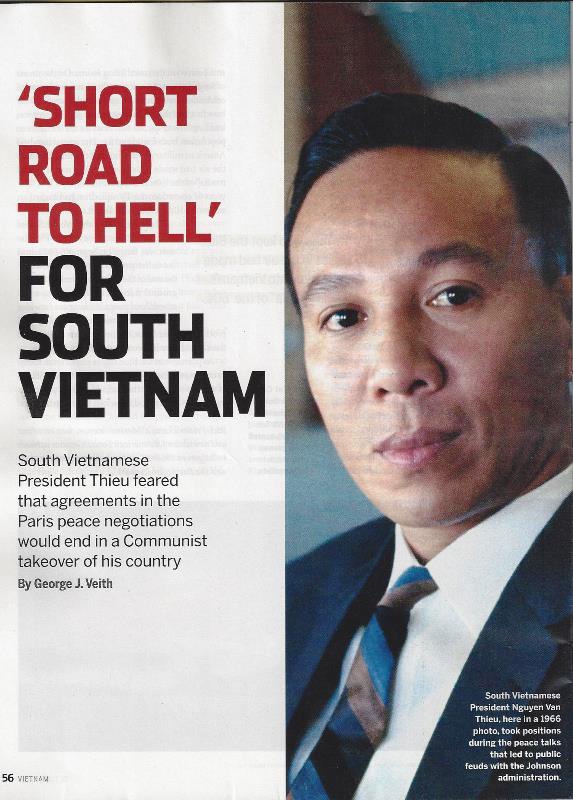

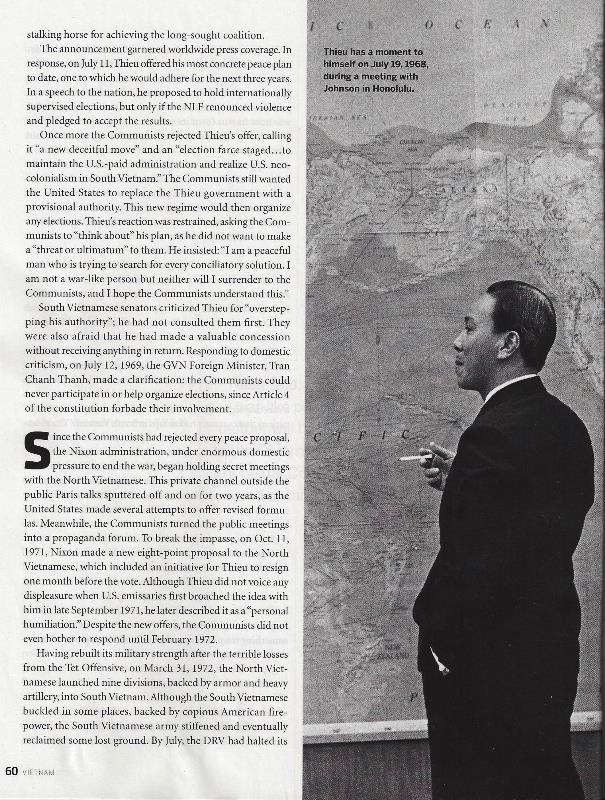

Đường ngắn tới… Heo

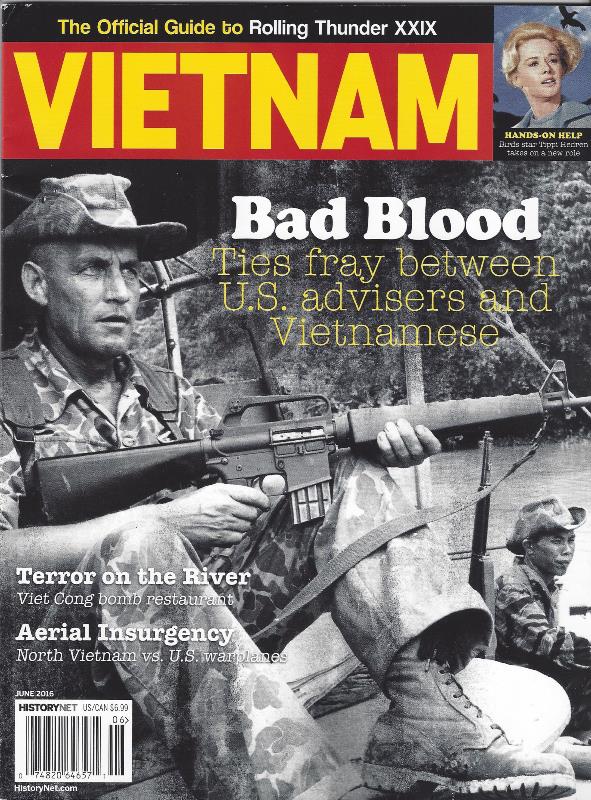

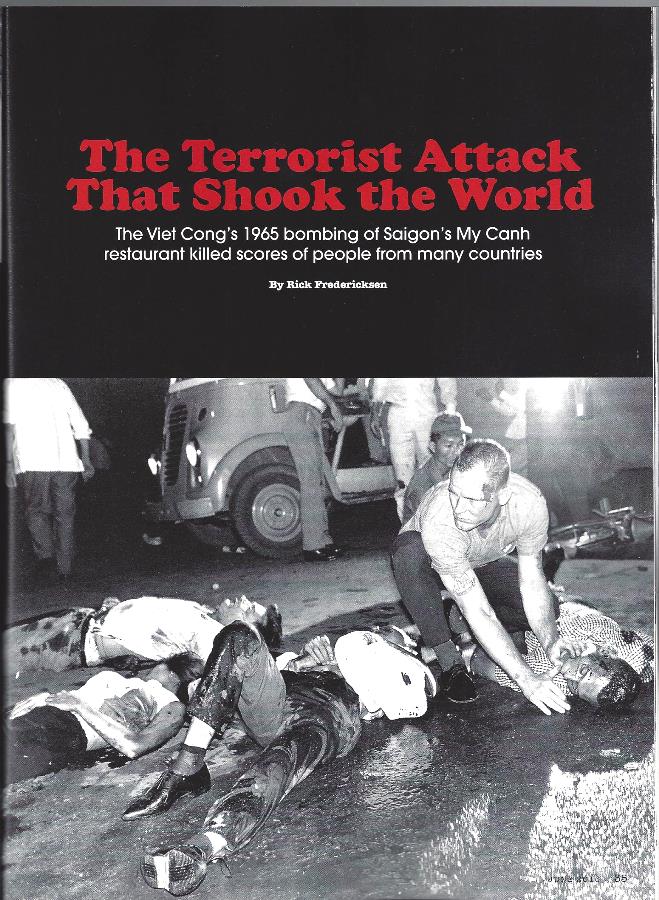

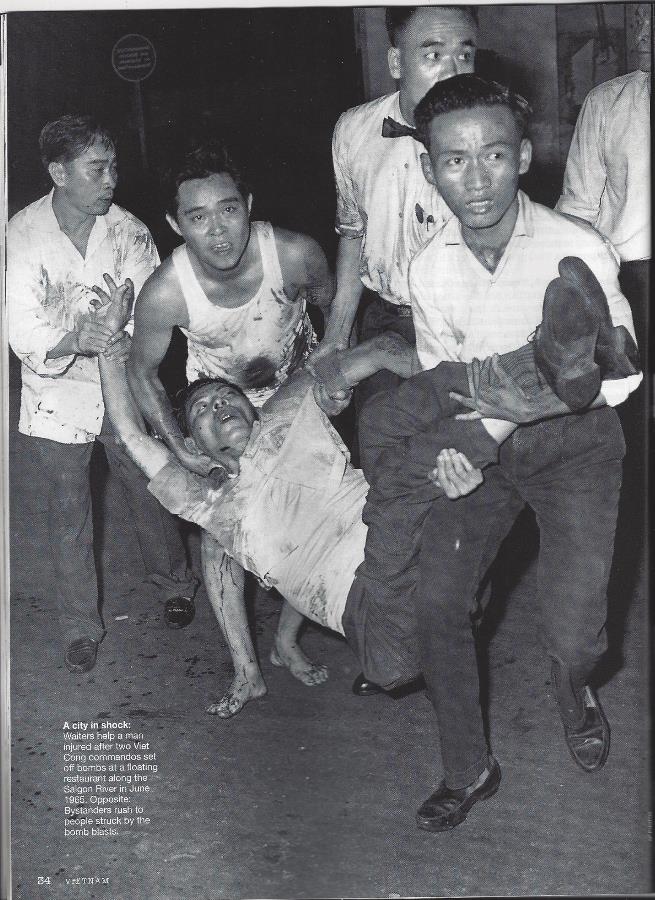

Heo 1: Ngay sau 30 Tháng 4, 1975 cho lũ Ngụy Heo 2: Dài dài sau đó, cho tới 40 năm sau, và sau nữa, cho xứ Mít. Nhìn hình, thì thấy Tông Tông Thiệu bảnh trai hơn bất cứ 1 tên nào ở Bắc Bộ Phủ! Được, được! “Short road to Hell”, cụm từ này, là của tuỳ viên báo chí của Tông Tông Thiệu, phát biểu, khi Nixon và Kissinger tìm đủ mọi cách đe dọa Thiệu, bắt ông phải ngồi vô bàn hội nghị ở Paris. Trên tờ Vietnam, số mới nhất Tháng 10, 2015, có bài viết của J. Veith, tác giả Tháng Tư Đen: Miền Nam thất thủ, Black April : The Fall of South Vietnam, 1973-75, viết về cú bức tử Miền Nam của Nixon và Kssinger. Bài viết là từ cuốn New Perceptions of the Vietnam War: Essays on the War: The South Vietnamese Experience, The Diaspora, and the Continuing Impact, do Nathalie Huynh Chau Nguyen biên tập: Sau khi dụ khị đủ mọi cách, Thiệu vẫn lắc đầu, Nixon dọa cắt hết viện trợ Mẽo, nếu không chịu ký hòa đàm. After persuasion had failed, Nixon threatened Thieu with the cessation of all American aid if he did not sign the accords Tổng Lú nhớ đọc nhe, vừa hôn đít O bá mà, vừa đọc nhe! Hôn rồi, về xứ Mít đọc, cũng được! Chúng ta giả dụ, sau khi Mẽo lại đi đêm với Tập, như Kissingger đã từng đi đêm với Mao, chúng yêu cầu, thịt thằng VC Mít nhe? Thơ Mỗi

Ngày

http://www.tanvien.net/new_daily_poetry/index.html

The luxury of tears Nước mắt cũng có hạn. Bữa nay đổ ra nhiều, thì bữa khác dè sẻn lại. Càng khóc nhiều, thì xã hội càng giầu thêm The old idea that people in developed countries suppress their emotions is being overturned. As Matthew Sweet discovers, we cry more as our societies get richer Matthew Sweet | April/May 2016 https://www.1843magazine.com/features/the-luxury-of-tears Những ngày TCS http://www.art2all.net/tho/tho_nqt/nhungngaytcs.html Trong

số những người tưởng niệm TCS khi anh vừa nằm xuống, GCC là thằng

đầu tiên.

Một bài viết, thoạt đầu ngắn, sau đây, sau, phát triển thành 1 bài dài thòng. Liền sau đó, GCC nhận được 1 cái mail, của 1 người bạn, kèm một đoạn trong bài viết của DT, về TCS, khi bài chưa được post, "xoa đầu" GCC tới chỉ! Giữa một rừng than khóc ki khu, thì bài Nguyễn Quốc Trụ, nhanh, ngắn nhưng giá trị. Vì chính xác và dũng cảm. DT Đoạn ngắn này, sau GCC được biết, bạn Lý Kiến Cắn [Lý Kiến Trúc] chơi liền, trong 1 số báo Văn Hoá của anh, ở Tiểu Saigon, tưởng niệm TCS. Tờ Văn của NXH, liền sau đó, cũng lấy đăng. Cái tít bài viết, thuổng Sơ Dạ Hương, Những ngày ở Saigon. Tks all. NQT Tôi biết Trịnh Công Sơn khi anh chưa nổi tiếng, và qua Nguyễn Đình Toàn, tại một bàn cà phê ở quán Cái Chùa, đường Tự Do, Sài Gòn. Nói chưa nổi tiếng, là đối với đa số công chúng thưởng ngoạn. Cùng với đà cuộc chiến leo thang, người dân miền nam ngày càng thấm nhạc của anh. Anh ngồi chung bàn với Toàn và tôi, nhưng cứ chốc chốc lại có một anh bạn trẻ nào đó, từ một bàn nào đó, tạt qua bàn, chỉ để nói chuyện hoặc hỏi thăm anh, và thường là về Huế, và cứ mỗi lần như vậy, anh đổi giọng nói. Khi nói với hai đứa chúng tôi, anh dùng giọng bắc. Toàn lúc đó phụ trách chương trình nhạc chủ đề trên đài phát thanh Sài Gòn, và hai người hình như có hẹn gặp nhau tại quán, ấy là tôi suy đoán ra như vậy. Thời gian này, tôi chưa để ý đến nhạc Trịnh Công Sơn. Nói rõ hơn, nó chưa thấm vào tôi. Phải tới khi đứa em trai mất, tới lượt tôi vào Trung Tâm Ba Quang Trung, trong những đêm cận Tết, nằm trên chiếc giường sắt lạnh lẽo, một anh chàng nào đó, chắc là quá nhớ bồ, cứ thế huýt sáo bài Tình Nhớ gần như suốt đêm, thế là tiếng nhạc bám riết lấy tôi, rứt không ra… Lúc này, tiếng nhạc của anh, đối với riêng tôi, qua lần gặp gỡ trên, như trút hết những âm tiết địa phương, và trở thành tiếng nói chung của cả miền nam, tức là của cả thế giới, vào thời điểm đó, khi cùng nói: hãy yêu nhau thay vì giết nhau. Bởi vì chưa bao giờ, và chẳng bao giờ miền nam chấp nhận cuộc chiến đó. Chính vì vậy, họ lãnh đạm với chính quyền, ưu ái với miền bắc, vì họ đều tin một điều, miền bắc sẽ kết thúc cuộc chiến, và người Mỹ sẽ ra đi. Như cả nhân loại tiến bộ, họ chỉ có thể tiên đoán đến đó. Nhạc Trịnh Công Sơn nói lên tiếng nói đó. Tính phản chiến của nhạc của anh, chính là tính phản chiến của cả một miền đất. Và cũng như cả nhân loại tiến bộ, chỉ tới sau vòng tay lớn rã ra, Trịnh Công Sơn mới hiểu. Một bạn văn của người viết, còn ở lại Sài Gòn, nhân lần gặp gỡ tại xứ người, đã kể chuyện, sau "giải phóng", có thời gian Trịnh Công Sơn bị Cộng Sản địa phương làm khó dễ, anh phải vô Sài Gòn, và có than thở với anh bạn văn kể trên. Anh nói, thì cứ dzô đây, gì thì gì, chắc cũng dễ thở hơn. Sài Gòn cưu mang Trịnh Công Sơn không phải chỉ lần đó. Theo như tôi được biết, những ngày cuộc chiến dữ dội, trong khi chúng tôi cứ thế theo nhau lên Trung Tâm Ba, Trịnh Công Sơn may mắn đã được đại tá không quân Lưu Kim Cương che chở. Trong số những quân cảnh tại thành phố, có người chỉ mong cơ hội "chộp" được Trịnh Công Sơn! Đại tá Lưu Kim Cương tử trận trong biến cố Mậu Thân, khi bảo vệ vòng đai phi trường Tân Sơn Nhất. Riêng tôi, tôi mong được như anh: được chết tại Sài Gòn. Xin vĩnh biệt.

manhhai

SAIGON, 7 May 1968 - Đại tá Lưu Kim Cương tại vành đai phía Tây Nam sân bay TSN Location: RVN, Tan Son Nhut. Photographer: SP5 J.F. Fitzpatrick, Jr. A Vietnamese Air Force Col, and the Tan Son Nhut CO, (right), fire a 50 cal. machine gun into enemy positions in the Old French Cemetery from atop a tank on the southwestern perimeter of Tan Son Nhut Air Base. Một Đại tá Không quân VN Chỉ huy trưởng căn cứ TSN (bên phải), bắn đại liên .50 vào vị trí địch tại Nghĩa trang QĐ Pháp từ trên một xe tăng tại vành đai phía tây nam Căn cứ KQ Tân Sơn Nhứt, [đó là Đại tá Lưu Kim Cương] 7 May 1968 Thơ Tháng Tư http://tanvien.net/new_daily_poetry/April_Poems.html

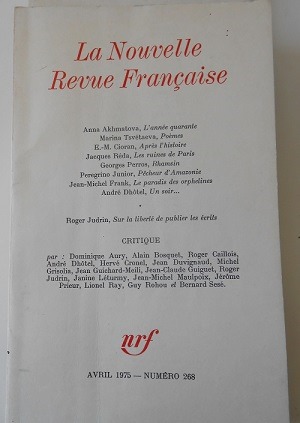

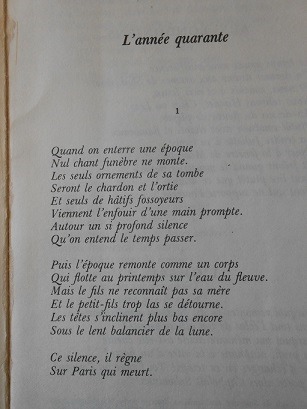

Số báo tuyệt vời, Tháng

Tư 1975

"Tôi mang cái chết đến

cho những người thân của tôi

Bài thơ làm

năm 1940, tức là cùng thời với Kinh Cầu.

Hết người này tới người kia gục xuống. Ôi đau đớn làm sao! Những nấm mồ Đã được tôi báo trước bằng lời." "I brought on death to my dear ones And they died one after another. O my grief! Those graves Were foretold by my word." Anna Akhmatova Saigon, qui meurt… Khi người ta chôn một thời đại Chẳng lời hát tang chế nào cất lên. Để trang trí cho mộ phần kia Chỉ thấy cúc gai với tầm ma Và chỉ có bọn đào huyệt hối hả Ra tay nhanh gọn vùi lấp nó. Giữa niềm im lặng sâu không đáy Khiến ta nghe được thời gian đi qua. Rồi thời đại nổi lên như thi thể Lênh đênh sông nước lúc xuân về. Nhưng đứa con chẳng còn nhìn ra mẹ Và thằng cháu quay lưng vì quá chán. Nhựng các cái đầu càng cúi thấp hơn Dưới đòn cân chậm chạp của vầng trăng . Niềm im lặng ấy trị vì Trên Paris đang chờ chết. Chân Phương dịch Tháng Tư 1975! Ban Mê Thuộc, Đà Nẵng, Nha Trang mất…Dân tình nhốn nháo, một số tìm cách ra đi, bạo lực chiến tranh trùm phủ bầu khí Sàigòn, ngoại ô xa đã bị pháo kích… Một buổi trưa rời đại học Văn Khoa và đám sinh viên đang hoảng loạn, tôi phóng mô tô qua Institut – viện Văn Hóa Pháp ở Đồn Đất – tìm chút tĩnh lặng trong mấy trang sách báo, cố duy trì thói quen trầm tư với chữ nghĩa dù binh lửa cận kề. Cầm trên tay LA NOUVELLE REVUE FRANCAISE , Avril 1975 – nguyệt san từ Paris vừa gửi đến – tôi mở ra trang đầu và gặp phải bài L’année quarante của nữ thi hào Anna Akhmatova. Đây là bài thơ khóc Paris vào năm 1940 khi nước Pháp thua trận và thủ đô bị quân Đức chiếm đóng. Tại sao nhà Gallimard lại cho đăng bài thơ này khi Sài gòn đang hấp hối từng ngày? Ban biên tập của NRF có chủ ý gì chăng? Dân Pháp làm gì không biết là Nam Việt Nam sắp mất! http://damau.org/archives/36641 V/v Câu hỏi của CP, có câu trả lời của 1 blogger dưới đây: * đề từ lấy từ bài thơ khu latin của nhà thơ vyacheslav ivanov * tháng 6 năm 1940 paris đầu hàng phát xít đức. bài thơ này được làm trong bối cảnh đó. Bản tiếng Anh, của Lyn Coffin: 1. When they bury an epoch, No psalms are read while the coffin settles, The grave will be adorned with a rock, With bristly thistles and nettles. Only the gravediggers dig and fill, Working with zest. Business to do! And it's so still, my God, so still, You can hear time passing by you. And later, like a corpse, it will rise Ride the river in spring like a leaf,- But the son doesn't recognize His mother, the grandson turns away in grief, Bowed heads do not embarrass, Like a pendulum goes the moon. Well, this is the sort of silent tune That plays in fallen Paris. Khi họ chôn một thời kỳ Không tụng ca được đọc khi hạ huyệt Ngôi mộ sẽ được điểm trang bằng 1 cục đá. Với cây kế tua tủa và tầm ma Chỉ mấy đấng thợ, đào, và sau đó lấp, mồ. Họ háo hức, hăm hở. Công việc mà! Và thật câm lặng, Chúa ơi, thật câm lặng! Bạn có thể nghe thời gian qua đi. Và sau đó, như 1 cái thây ma, nó trỗi dậy Bay trên mặt sông vào mùa xuân như 1 chiếc lá – Nhưng ông con trai không nhận mẹ Đứa cháu trai bỏ đi trong đau khổ Những cái đầu cúi xuống đâu làm phiền ai Như con lắc, mảnh trăng đong đưa Đúng rồi, đúng điệu nhạc âm thầm đó Dân Sài Gòn chơi, ngày mất Sài Gòn. [Bản của GCC] Trần Hồng Tiệm FB Yesterday at 3:36pm · tháng 8 năm 1940 thành phố của người, julian vyach. ivanov khi người ta chôn thời đại trước huyệt không hát thánh ca cúc gai cùng với tầm ma sẽ phải tô điểm cho mộ chỉ có phu huyệt hối hả chôn cất. đợi chờ được sao lặng im, chúa ơi, im quá nghe thấy mỗi thời gian đi sau khi thời đại nổi lên giống thây trên dòng sông xuân nhưng con không nhận ra mẹ còn cháu quay lưng trong buồn đầu người cúi xuống thấp nữa như con lắc ở mặt trăng và thế - trên paris đã chết lặng im hiện đang bao trùm ngày 5 tháng 8 năm 1940 tại nhà sheremetevsky anna akhmatova * đề từ lấy từ bài thơ khu latin của nhà thơ vyacheslav ivanov * tháng 6 năm 1940 paris đầu hàng phát xít đức. bài thơ này được làm trong bối cảnh đó. Август 1940 То град твой, Юлиан! Вяч. Иванов Когда погребают эпоху, Надгробный псалом не звучит, Крапиве, чертополоху Украсить ее предстоит. И только могильщики лихо Работают. Дело не ждет! И тихо, так, Господи, тихо, Что слышно, как время идет. А после она выплывает, Как труп на весенней реке,- Но матери сын не узнает, И внук отвернется в тоске. И клонятся головы ниже, Как маятник, ходит луна. Так вот - над погибшим Парижем Такая теперь тишина. 5 августа 1940 Шереметевский Дом Анна Ахматова #thodichdonga #thongadonga https://www.facebook.com/donga01?fref=nf Note: Tks. NQT

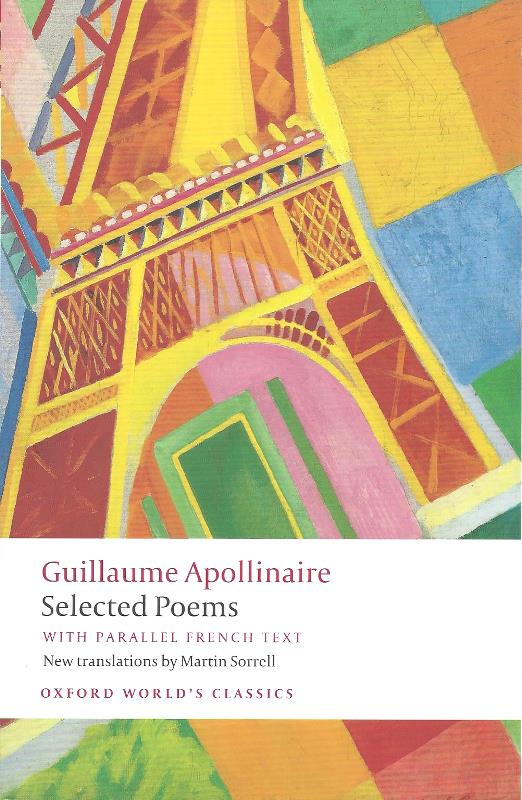

LE HIBOU Mon pauvre coeur est un hibou Qu'on cloue, qu'on décloue, qu'on récloue. De sang, d'ardeur, il est à bout. Tous ceux qui m'aiment, je les loue. Trái tim đáng thương của Gấu là con cú Người ta đóng đính, nhổ đinh, rồi lại đóng đinh Máu me, yếu xìu, mệt nhoài Tất cả những kẻ yêu tôi, tôi đều mướn họ THE OWL My poor heart is like an owl, Nailed, un-nailed, and nailed again. Gutless, weak, exsanguinate. Loyal friends I ululate. LA PUCE Puces, amis, amantes même, Qu'ils sont cruels ceux qui nous aiment! Tout notre sang coule pour eux. Les bien-aimés sont malheureux. Chấy rận, bạn quí, và ngay cả người yêu Tàn nhẫn làm sao, những kẻ yêu chúng ta Máu của chúng ta chảy là vì họ Những kẻ yêu thương thì mới bất hạnh làm sao THE FLEA Fleas, friends, even lovers, How cruel are those who love us! They empty us of all our blood. Unhappy are the well-beloved.

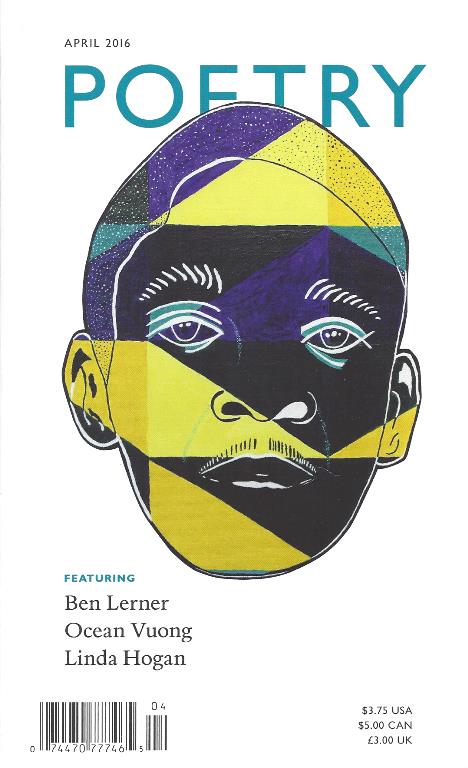

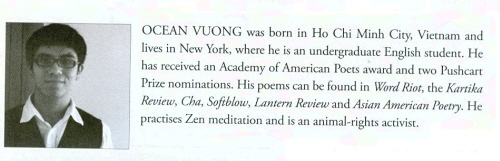

OCEAN VUONG

Toy Boat

For Tamir Rice yellow plastic black sea eye-shaped shard on a darkened map no shores now to arrive - or depart no wind but this waiting which moves you as if the seconds could be entered & never left toy boat - oarless each wave a green lamp outlasted toy boat toy leaf dropped from a toy tree waiting waiting as if the sp- arrows thinning above you are not already pierced by their own names

Note: Trên Tin Văn đã giới thiệu Ocean Vuong, qua bài thơ xử VC. Bài thơ mới, trên số báo Thơ, cũng hợp với Tháng Tư, thay vì thuyền nhân, thì chúng ta có thuyền đồ chơi con nít Ocean Vuong The Photo http://www.tanvien.net/TV_Diary_New/6.html After the infamous 1968 photograph of a Viet Cong officer executed by South Vietnam's national police chief. What hurts the most is not how death is made permanent by the cameras flash the irony of sunlight on gunmetal but the hand gripping the pistol is a yellow hand, and the face squinting behind the barrel a yellow face. Like all photographs this one fails to reveal the picture. Like where the bullet entered his skull the phantom of a rose leapt into light, or how after smoke cleared from behind the fool with blood on his cheek and the dead dog by his feet a white man was lighting a cigarette. ASIA LITERARY REVIEW SUMMER 2010 Một "Bóng Đen Giữa Ban Ngày" Khác Sài Gòn có phải

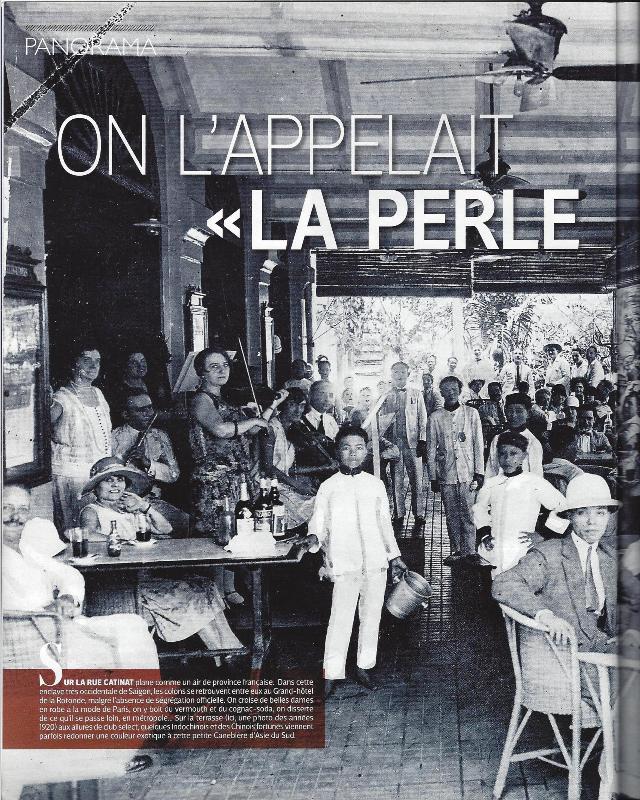

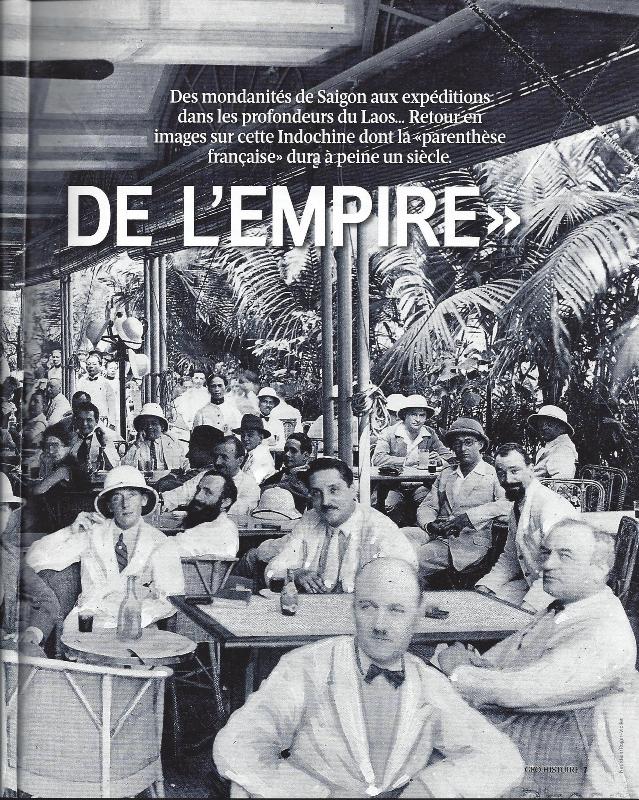

là 'Hòn ngọc Viễn Đông'?

Trương

Thái Du Gửi tới BBC Tiếng Việt từ Sài Gòn

http://www.bbc.com/vietnamese/forum/2016/04/160401_saigon_truong_thai_du_comments?SThisFB Cái tên Hòn Ngọc Viễn Đông, là Tẩy ban cho Sài Gòn, và quả đúng như thế, và sở dĩ được như thế, thì vì nhiều lý do, trong có cái gọi là "mentalité" của dân Miền Nam, và cái gọi là “văn minh” của Tẩy. Tẩy đối xử với dân Miền Nam ngang hàng, không phân biệt. Điều này được những nhà văn, thí dụ hai đấng, là Graham Greene, trong "Ways of Escape" đã có những dòng ca ngợi thần sầu về Sài Gòn, và Maugham, trong bài viết về Huế, có trên Tin Văn. Và quả đúng là quá khứ không thể nào lập lại, và điều này phần lớn là do Bắc Kít. Cái độc, cái ác của chúng làm biến đổi xã hội Miền Nam đến tận gốc rễ, không làm sao gượng lại được nữa.

HUẾ HUE

IS A pleasant little town with something of the leisurely air of a cathedral

city in the West of England, and though the capital of an empire it is

not imposing. It is built on both sides of a wide river, crossed by a

bridge, and the hotel is one of the worst in the world. It is extremely

dirty, and the food is dreadful; but it is also a general store in which

everything is provided that the colonist may want from camp equipment and

guns, women's hats and men's reach-me-downs, to sardines, pate de foie

gras, and Worcester sauce; so that the hungry traveler can make up with

tinned goods for the inadequacy of the bill of fare. Here the inhabitants

of the town come to drink their coffee and fine in the evening and the

soldiers of the garrison to play billiards. The French have built themselves

solid, rather showy houses without much regard for the climate or the environment;

they look like the villas of retired grocers in the suburbs of Paris.

The French carry France to their colonies just as the English carry England to theirs, and the English, reproached for their insularity, can justly reply that in this matter they are no more singular than their neighbors. But not even the most superficial observer can fail to notice that there is a great difference in the manner in which these two nations behave towards the natives of the countries of which they have gained possession. The Frenchman has deep down in him a persuasion that all men are equal and that mankind is a brotherhood. He is slightly ashamed of it, and in case you should laugh at him makes haste to laugh at himself, but there it is, he cannot help it, he cannot prevent himself from feeling that the native, black, brown, or yellow, is of the same clay as himself, with the same loves, hates, pleasures and pains, and he cannot bring himself to treat him as though he belonged to a different species. Though he will brook no encroachment on his authority and deals firmly with any attempt the native may make to lighten his yoke, in the ordinary affairs of life he is friendly with him without condescension and benevolent without superiority. He inculcates in him his peculiar prejudices; Paris is the centre of the world, and the ambition of every young Annamite is to see it at least once in his life; you will hardly meet one who is not convinced that outside France there is neither art, literature, nor science. But the Frenchman will sit with the Annamite, eat with him, drink with him, and play with him. In the market place you will see the thrifty Frenchwoman with her basket on her arm jostling the Annamite housekeeper and bargaining just as fiercely. No one likes having another take possession of his house, even though he conducts it more efficiently and keeps it in better repair that ever he could himself; he does not want to live in the attics even though his master has installed a lift for him to reach them; and I do not suppose the Annamites like it any more than the Burmese that strangers hold their country. But I should say that whereas the Burmese only respect the English, the Annamites admire the French. When in course of time these peoples inevitably regain their freedom it will be curious to see which of these emotions has borne the better fruit. The Annamites are a pleasant people to look at, very small, with yellow flat faces and bright dark eyes, and they look very spruce in their clothes. The poor wear brown of the color of rich earth, a long tunic slit up the sides, and trousers, with a girdle of apple green or orange round their waists; and on their heads a large flat straw hat or a small black turban with very regular folds. The well-to-do wear the same neat turban, with white trousers, a black silk tunic, and over this sometimes a black lace coat. It is a costume of great elegance. But though in all these lands the clothes the people wear attract our eyes because they are peculiar, in each everyone is dressed very much alike; it is a uniform they wear, picturesque often and always suitable to the climate, but it allows little opportunity for individual taste; and I could not but think it must amaze the native of an Eastern country visiting Europe to observe the bewildering and vivid variety of costume that surrounds him. An Oriental crowd is like a bed of daffodils at a market gardener's, brilliant but monotonous; but an English crowd, for instance that which you see through a faint veil of smoke when you look down from above on the floor of a promenade concert, is like a nosegay of every kind of flower. Nowhere in the East will you see costumes so gay and multifarious as on a fine day in Piccadilly. The diversity is prodigious. Soldiers, sailors, policemen, postmen, messenger boys; men in tail coats and top hats, in lounge suits and bowlers, men in plus fours and caps, women in silk and cloth and velvet, in all the colors, and in hats of this shape and that. And besides this there are the clothes worn on different occasions and to pursue different sports, the clothes servants wear, and workmen, jockeys, huntsmen, and courtiers. I fancy the Annamite will return to Hue and think his fellow countrymen dress very dully. Somerset Maugham: The Skeptical Romancer

Bắc

Kít rêu rao giải phóng Nam Kít. Sự thực, chúng

đem tới, và tiêm chủng vào khí hậu con người

Nam Kít cái độc cái ác bản chất của chúng,

và lấy đi, những cái chúng không bao giờ có,

và được hưởng, là tự do, dân chủ, sống thoải mái

giữa con người với con người.

Hãy thử đọc 1 đoạn Somerset Maugham viết, là biết: The Frenchman has deep down in him a persuasion that all men are equal and that mankind is a brotherhood. He is slightly ashamed of it, and in case you should laugh at him makes haste to laugh at himself, but there it is, he cannot help it, he cannot prevent himself from feeling that the native, black, brown, or yellow, is of the same clay as himself, with the same loves, hates, pleasures and pains, and he cannot bring himself to treat him as though he belonged to a different species. Though he will brook no encroachment on his authority and deals firmly with any attempt the native may make to lighten his yoke, in the ordinary affairs of life he is friendly with him without condescension and benevolent without superiority. He inculcates in him his peculiar prejudices; Paris is the centre of the world, and the ambition of every young Annamite is to see it at least once in his life; you will hardly meet one who is not convinced that outside France there is neither art, literature, nor science. But the Frenchman will sit with the Annamite, eat with him, drink with him, and play with him. In the market place you will see the thrifty Frenchwoman with her basket on her arm jostling the Annamite housekeeper and bargaining just as fiercely. No one likes having another take possession of his house, even though he conducts it more efficiently and keeps it in better repair that ever he could himself; he does not want to live in the attics even though his master has installed a lift for him to reach them; and I do not suppose the Annamites like it any more than the Burmese that strangers hold their country. But I should say that whereas the Burmese only respect the English, the Annamites admire the French. When in course of time these peoples inevitably regain their freedom it will be curious to see which of these emotions has borne the better fruit. Tẩy thực dân đối xử với Nam Kít, như thế, trong khi lũ Yankee mũi tẹt sau khi lấy được Miền Nam, đối xử với họ như thế nào? Cái chuyện Bắc Kít không hề biết đến cái gọi là tự do, dân chủ, người đối xử như người với người, là sự thực, và là chuyện thường ngày ở cả xứ Mít hiện nay. Sự kiện chưa từng biết đến dân chủ là gì, là lịch sử bốn ngàn năm của xứ Bắc Kít, và cũng là cái chuyện của xứ Nga Xô. Nói 1 cách ẩn dụ, thì đây là câu chuyện Bóng Đêm Giữa Ban Ngày, được Koestler, bằng con mắt của 1 nhà văn, cô đọng nó vào 1 cuốn sách mỏng dính. Trong bài viết mới nhất về nó, nhân nguyên tác mới tìm lại, Michael Scammell viết: Like other European Communists, Koestler had struggled to make sense of these trials, and having utterly failed to do so, he handed in his Party card. He started his novel in an attempt to decipher the tortured logic of the confessions, taking as his hero a Bukharin-like disillusioned high Party official, Nikolai Salmanovich Rubashov. In the course of the novel Rubashov is interrogated by two secret police officials, the “good cop” Ivanov (a former friend) and the “bad cop” Gletkin (a younger, robotic apparatchik), who between them force him to review his life as a Party leader and convince him that by following his ideals he has disobeyed the Party line and has violated his oath of loyalty. In Party-speak, he was guilty of counterrevolutionary activities. Broken by the logic of his interrogators, Rubashov listlessly confesses at a public trial and is taken to a prison cellar where he is executed with a bullet in the head. The novel’s provisional title was “The Vicious Cycle” and after that “Rubashov.” Những vụ án dởm, mà Koestler dựa vào chúng, để xây dựng tác phẩm, vẫn đang hàng ngày xẩy ra ở Xứ Mít VC. Cái tít của cuốn sách, thoạt kỳ thuỷ là “Vòng Tròn Xấu Xa, Ma Quỉ”, rồi “Rubashov”, rồi “Bóng Đêm Giữa Ban Ngày”. Michael Scammell viết, thật khó mà tin rằng, 1 nhà văn lại đẻ ra vài ấn bản khác nhau như thế, về tác phẩm đầu tay của mình: It’s hard to believe the same author could have produced two such different versions of his own novel, until one remembers that Koestler was working from the English edition the second time around. In the intervening four years he had learned to think and write in English himself, which helps to explain why the discrepancies were so wide. When he ran into trouble with his translation into German he consulted some native German speakers for advice and showed a sample to Rudolf Ullstein, scion of the great German publishing house (for which Koestler himself had worked in the 1930s). Ullstein noted that Koestler was using “a great deal of foreign words instead of German expressions” in his translation and asked for permission to change them into idiomatic German. There is irony here, for the English translation Koestler worked from is itself full of German words and phraseology, a neat reversal. After further drudgery, Koestler acknowledged his limitations and asked another German friend to revise the entire translation for him, but the final version, with all its weaknesses, was still his. |