|

12. One great poet of her generation Tsvetaeva did meet; in 1916, she met young Osip Mandelstam. They had a brief affair during the Civil War. Mandelstam visited her so often-by train from St. Petersburg-that one friend joked, "I wonder if he is working for the railways." Years later, Nadezhda Mandelstam, the poet's widow, recalled: The friendship with Tsvetaeva, in my opinion, played an enormous role for Mandelstam 's work. It was a bridge on which he walked from one period of his work to another. With poems to Tsvetaeva begins his second book of poems, Tristia. Mandelstam's first book, Stone, was the restrained, elegant work of a Petersburg poet. Tsvetaeva's friendship gave him her Moscow, lifting the spell of Petersburg's elegance. It was a magical gift, because with Petersburg alone, without Moscow, there is no freedom of full breath, no true feeling of Russia, no conscience. I am sure that my own relationship with Mandelstam would not have been the same if on his path he had not met, so bright and wild, Marina. She opened in him the love of life, the ability for spontaneous and unbridled love of life, which struck me from the first minute I saw him. According to Mme. Mandelstam, "Tsvetaeva had a generosity of soul and a selflessness which had no equal. It was directed by her willfulness and impetuosity, which too, had no equal." 13. A fact: the Revolution brought Tsvetaeva poverty and the five-year-long absence of her husband, who joined the White Army and fought the Revolutionaries in Crimea and elsewhere. A fact: after the Revolution, Tsvetaeva almost starved. She left both of her daughters in an orphanage where it was said they would be better fed, and one of them, the younger, Irina, died of starvation. When my child died in Russia from hunger and I learnt of this- simply on the street from a strange person-("Little Irina your daughter?- Yes-She died. Yesterday died. Tomorrow we will bury her.")-and I kept silent three months-not a word of death-to anyone-so she [the child] did not die finally, and still (in me)- lived. This is why your Rilke did not mention my name. To name [call/speak] -is to take apart: to separate self from thing. I don't name anyone-ever. This too, is a lesson found in her poetics: Marina Tsvetaeva, the poet so obsessed with the Russian language, the Russian poet of her generation, the poet who wrote elegies for everyone else-including the living-at her own elegiac moment, chose not to speak. 12 Một nhà thơ lớn của thời của bà, Tsvetaeva đã từng gặp; vào năm 1916, bà gặp Osip Mandelstam trẻ. Họ có 1 cuộc tình ngắn ngủi trong thời kỳ Nội Chiến. Mandelstam thường xuyên thăm bà - bằng hoả xa từ St. Petersburg – một người bạn thân nói đùa, hay là anh ta là nhân viên hỏa xa. Những năm sau đó, bà vợ góa của Mandelstam nhớ lại: Tình bạn với Tsvetaeva theo tôi, đã ảnh hưởng lớn lên thơ của Mandelstam. Nó là cây cầu mà nhờ nó mà nhà thơ bước từ một giai đoạn của mình, qua 1 giai đoạn khác. Với những bài thơ với Tsvetaeva, bắt đầu cuốn thơ thứ nhì của anh, Tristia. Tập thơ đầu, Stone, là 1 tác phẩm câu thúc, thanh nhã, của nhà thơ của St. Petersburg. Tình bạn với Tsvetaeva cho anh, Moscow của bà, thoát ra khỏi lời nguyền của sự lịch lãm của St. Petersburg. Đúng là 1 món quà thần kỳ, bởi là vì với chỉ Petersburg không thôi, không có Moscow, thì sẽ thiếu khí trời, thiếu sự tự do của hơi thở trọn vẹn, đếch có tình tự thực, cảm nghĩ thực, về Nga xô, đếch có luôn lương tâm, ý thức… Ui chao, đọc, thì lại nghĩ đến Gấu Cà Chớn: Giả như đếch có Xề Gòn? Phan Thiền Sư & kiêm nhà báo, nhận ra điều này, khi viết về GCC: Tác giả Nguyễn Quốc Trụ đã nổi tiếng từ thập niên 1960s tại Sài Gòn, với các thể loại truyện ngắn, tạp ghi và biên khảo văn học. Ra hải ngoại, ông viết bài cho nhiều báo, chuyên khảo về văn học Việt Nam và thế giới, đang thực hiện trang web riêng ở địa chỉ tanvien.net. Với ngôn ngữ rất là Bắc Kỳ, và gần suốt một đời trưởng thành và sống tại Miền Nam, văn của NQT đã trở nên đa dạng và phức tạp hơn hầu hết những người cầm bút cùng thời. Một sự kiện: Cách Mạng đem tới cho Tsvetaeva nghèo đói và sự vắng mặt kéo dài 5 năm trời của người chồng, gia nhập Bạch Vệ và chống lại Cách Mạng ở Crimea, và đâu đó. Sự kiện: Sau Cách Mạng, Tsvetaeva hầu như chết đói. Bà để hai đứa con ở viện mồ côi, nơi người ta nói, chúng sẽ được nuôi nấng khá hơn, và một trong hai đứa, đứa em, Irina, chết đói. Khi con tôi chết ở Nga vì đói, và biết được điều này, ở trên đường phố, qua 1 người lạ (Cháu gái của bà là Irina? Vâng. Cháu mất rồi. Mất hôm qua. Ngày mai chúng tôi chôn cháu), tôi nín lặng, không nói cho ai biết trong ba tháng trời, kể như con tôi, vẫn còn sống, ở trong tôi. Cũng, kể như thế, Rilke của bạn không nhắc tên tôi. Gọi tên ai là chia ly, là cách lìa, là phân ly cái tôi ra khỏi sự vật. Tôi không khi nào, chẳng bao giờ gọi tên bất cứ ai, nữa. 17.

Having arrived abroad, Tsvetaeva

wrote, "My motherland is any place with a writing desk, a

window, and a tree by that window." She wrote of exile: "For lyric

poets and fairy-tale authors, it is better that they see their motherland

from afar-from a great distance." Compare this to Gogol: " ... my

nature is the ability to imagine a world graphically only when I have

moved far away from it. That is why I can write about Russia only in

Rome. Only there does it stand before me in all its hugeness.'?" Again,

Tsvetaeva: "Russia (the sound of the word) no longer exists, there

exist four letters: USSR-I cannot and will not go where there are no

vowels, into those whistling consonants. And, they won't let me

there, the letters won't open." So Tsvetaeva spent seventeen years in France. France did not allow foreigners to have regular jobs and papers were hard to obtain. But Paris had a large concentration of journals, publishing houses, and emigre intellectuals. Tsvetaeva wrote, "I get numerous invitations, but I cannot show myself because there is no silk dress, no stockings, no patent leather shoes, which is the local uniform. So 1 stay at home, accused from all sides of being too proud,'?" After Hitler assumed power in Germany, the USSR began to look brighter to many emigres. After much family drama (which we need not explore here), Tsvetaeva, without any particular nostalgic feeling, returned to Moscow on June 18,1939. Ra hải ngoại, Tsvetaeva viết, “Đất mẹ của tôi là bất cứ chỗ nào, với một cái bàn viết, một cửa sổ, và 1 cái cây kế bên cái cửa sổ”. Bà viết về lưu vong, “Với những nhà thơ trữ tình, và những tác giả viết chuyện thần tiên, tốt nhất là họ nên nhìn đất mẹ từ xa, càng xa chừng nào tốt chừng đó” So với Gogol, “….tôi là thứ người chỉ có thể tưởng tượng ra thế giới đồ thị, ‘vẽ bản đồ’, khi tôi ở xa nó. Chính vì thế mà tôi chỉ có thể viết về Nga, từ La Mã. Chỉ ở đó, tôi mới cảm thấy quê hương hùng vĩ lớn lao biết là chừng nào!” Lại vẫn Tsvetaeva, “Nga (cái tiếng, cái âm thanh của từ này), đếch còn hiện hữu, thay vì thế, thì là bốn con chữ, USSR – tôi không thể tới đó, nơi đếch có nguyên âm, phụ âm thì nghe sao lùng bùng, ở đó chúng không cho tôi vô, những con chữ đếch chịu mở” from In Memory of Marina Tsvetaeva

It's as hard

to imagine you don't exist as to imagine you a miser-millionaire among starving sisters. What can I do for you? Say. There's a quiet reproach in the way you've gone your way. Losses are riddles. In vain I try to find an answer. Death has no outline. Half-words, tongue-slips, delusion - and only faith in resurrection by way of direction. Winter makes a splendid memorial: a glimpse of twilight, add currants, pour on wine - and there's your remembrance meal! An apple tree in a drift, the town wrapped in snow, seemed all year long to be your grave, your headstone. Pasternak Từ Tưởng Niệm Marina Tsvetaeva

Thật khó mà tưởng

tượngEm không có ở trên cõi đời này Cũng khó, thật khó mà nghĩ Em là một tỉ phú khốn khổ Giữa mấy chị em chết đói Anh làm gì được cho Em? Hãy nói Có tí bùi ngùi, nếu không muốn nói, trách móc nhẹ, thầm lặng Về cái cách Em chơi, đời của Em Những kẻ thua thiệt thì giống như là những thai đố Thật vô ích Khi anh cố tìm câu trả lời. Cái chết quả đúng là không có phác thảo Ấp úng, lỡ lời, ảo tưởng – Và chỉ có niềm tin vào sự tái sinh Bằng đường lối chỉ đạo Mùa đông tạo tưởng nhớ tuyệt vời: Một thoáng chạng vạng Cộng thêm vài trái nho, rót ly hồng đào Vậy là có bữa tưởng nhớ dành cho Em! Một cây táo bồng bềnh Thành phố trùm tuyết Năm dài tháng đợi Mộ của Em, bia của Em Đối diện Thượng Đế Em tới với Người, từ đất Đâu có khác, trước đó, Những ngày của Em đã tới ngày chót

I will win you away from every earth, from every

sky, Both your wings, as they yearn for the ether, become

unfurled, Tôi sẽ thắng anh, từ bất cứ mảnh đất, bất cứ

vòm trời Tôi sẽ thắng anh, từ bất cứ mảnh đất, bất cứ

vòm trời, RHYTHMS OF THE SOUL:

MARINA TSVETAEVA Nhịp của linh hồn: Marina Tsvetaeva There are many souls in me, Marina Tsvetaeva once wrote, and readers of her work often have the feeling that spiritual forces compete in every line she ever wrote. The emotional intensity of her writing, whether in prose or in poetry, seems startlingly able to bend her language into unimaginable new shapes. That linguistic fearlessness makes her a challenge for translators, but readers of this volume will palpably sense the sheer force of her language. In choosing and ordering these writings, IIya Kaminsky and Jean Valentine create force fields across the poems and prose fragments; they have lifted a small number of texts from the massive Tsvetaeva legacy, creating luminous new versions for us to behold. The translations attain a kind of light-showered clarity before our eyes, with each scrap of text commanding our focused attention as if nothing else mattered from Poem of the End

Outside of town! Understand?

Out! We're outside the walls. Outside life- where life shambles to lepers. The Jew-ish quarter. It's a hundred times an honor to stand with the Jews- for anyone not scum. Outside the walls, we stand. Outside life- the Jew-ish quarter. Life is for converts only! Judases of all faiths. Go find a leper colony! Or hell! Anywhere-just not life-life loves only liars, lifts its sheep to blades. I stomp on my birth certificate, rub out my name! Go find a leper colony! With David's star, I stand- I spit on my passport. And back in the town they're saying, It's only right- the Jews don't want to live! Ghetto of the chosen! The wall and ditch. No mercy. In this most Christian of worlds all poets-are Jews. PRAGUE, 1924 Thơ của Tận Cùng

Ra ngoài thành phố! Hiểu không! Ngoài!Chúng ta ở bên ngoài những bức tường. Bên ngoài cuộc đời – Nơi đời lê lết tới những người cùi Khu Do-Thái Hàng trăm lần vinh dự Đứng với người Do Thái Bởi là vì chẳng ai là cặn bã Bên ngoài những bức tường, chúng ta đứng. Bên ngoài đời Ổ, Khu, Xóm Do-Thái Đời chỉ dành cho những kẻ cải đạo Những tên Judas của tất cả những niềm tin Hãy đi kiếm một thuộc địa cùi! Hay địa ngục! Bất cứ đâu – Đời không thế Đời chỉ yêu những kẻ dối trá Nhấc những con cừu của nó tới những lưỡi dao Tôi chà đạp tờ khai sinh của tôi Chà tên của tôi ra khỏi nó! Hãy đi kiếm thuộc địa cùi! Với ngôi sao David, tôi đứng sững – Tôi nhổ lên tờ thông hành Trở lại thành phố, chúng nói, đúng, quá đúng, như thế - Những tên Do Thái không muốn sống! Ghetto của những kẻ được chọn lựa! Bức tường và hào rãnh Không, cám ơn. Trong những từ ngữ cực Ky Tô Tất cả những thi sĩ - đều là Do Thái Prague 1924 MARINA TSVETAEVA Volkov. People have referred to you as a poet belonging to Akhmatova's circle. She loved you and supported you at difficult moments, but from talking with you I know that the work of Marina Tsvetaeva had a much greater influence on your development as a poet than did Akhmatova's. Tsvetaeva was the poet of your youth. When you speak about Tsvetaeva's poetry, you often call it Calvinistic. Why? Brodsky. Above all, bearing in mind just how unprecedented her syntax was. This allowed-or rather, forced-her to spell everything out in her verse. In principle, Calvinism is a very simple matter: it is man keeping strict accounts with himself, with his conscience and consciousness. In that sense, by the way, Dostoevsky is a Calvinist as well. A Calvinist, to put it briefly, is someone who is constantly declaring Judgment Day against himself-as if in the absence (or impatient for) the Almighty. In this sense, there is no other poet like her in Russia. Soloman Volkov: Conversations with Joseph Brodsky Trong “Trò chuyện với Brodsky”, của Solomon Volkov, có 1 chương dành cho Marina Tsvetaeva. Brodsky coi Tsvetaeva là “nhà thơ thứ nhất của thế kỷ 20”, nhà thơ của thời trẻ tuổi của ông, và thơ của bà, có tính Calvinistic, và ông giải thích, Calvinism thì cũng đơn giản thôi: đó là 1 người bám chặt vào chính mình, với ý thức và lương tâm của mình. Theo nghĩa này, thì Dos là 1 Calvinist. Nói ngắn gọn, Calvinist là 1 kẻ lúc nào cũng phán Ngày Tận Thế, chống lại anh ta. Brodsky cho biết, ông đọc thơ Tsvetaeva, khi ông 19, hoặc 20. Không phải trong những cuốn sách mà đặc biệt là trong những bản in dưới hầm, but exclusively in samizdat typescript. Ông không nhớ là ai đưa cho ông, và khi đọc “Thơ núi”, “Poem of the Mountain” mọi thứ clich 1 phát, everything clicked. Chưa từng có gì đọc trước đó, ở Nga, gây ấn tượng như vậy: Nothing I’ve read in Russian has produced such an impression…. Tất cả thi ca của bà có thể giản lược, qui về câu này, If the content of Tsvetaeva’s poetry could be reduced to some formula then it’s this: To your insane world But one reply – I refuse Bài trò chuyện này cũng thật là tuyệt, và quái làm sao, Gấu nhận ra, 1 cái gì đó, ở TTT, ở đây, qua cái thái độ quá nghiêm khắc với chính mình của ông. Lũ bạn bè của ông, sở dĩ quê ông, cũng vì cái cú, "I refuse", y chang! Có vẻ như sau cùng, ông cũng có 1 người bạn, qua DC - như GCC, qua Joseph Huỳnh Văn. Một tên đủ rồi. Vị bằng hữu K. của trang TV, chúc GCC nhân 1 SN, chẳng cần thằng nào, chẳng nghĩ đến thằng nào, lõ cũng như tẹt, chỉ mần thơ là được rồi! OK Salem! Tks NQT Không có thơ không có chiều cao Il n’est pas poésie sans hauteur Philippe Jaccottet Adam Zagajewski mở ra bài viết Cái đê tiện và cái thăng hoa, The Shabby and the Sublime, trong In Defense of Ardor. Czeslaw cũng nói như thế, về thơ Brodsky, và chính Brodsky cũng nghĩ về thơ, như thế, không có đẳng cấp, không có thơ. In one of his essays Brodsky calls Mandelstam a poet of culture. Brodsky was himself a poet of culture, and most likely that is why he created in harmony with the deepest current of his century, in which man, threatened with extinction, discovered his past as a never-ending labyrinth. Penetrating into the bowels of the labyrinth, we discover that whatever has survived from the past is the result of the principle of differentiation based on hierarchy. Mandelstam in the Gulag, insane and looking for food in a garbage pile, is the reality of tyranny and degradation condemned to extinction. Mandelstam reciting his poetry to a couple of his fellow prisoners is a lofty moment, which endures. Milosz Trong một tiểu luận, Brodsky gọi Mandelstam là một thi sĩ của văn hóa. Brodsky chính ông, cũng là 1 thi sĩ của văn hóa, và hẳn là vì lý do này, ông tạo sự hài hòa với dòng sâu thẳm của thế kỷ, trong đó con người, bị đe dọa mất mẹ cái giống người, khám phá ra quá khứ như là một mê cung chẳng hề có tận cùng. Lặn sâu vô mê cung, chúng ta khám phá ra cái gì sống sót quá khứ là kết quả của nguyên lý phân biệt dựa trên đẳng cấp. Mandelstam, ở trong Gulag, điên khùng bới đống rác tìm đồ ăn, [ui chao lại nhớ Giàng Búi], là thực tại về độc tài bạo chúa và sự băng hoại thoái hoá bị kết án phải tuyệt diệt. Mandelstam đọc thơ cho vài bạn tù là khoảnh khoắc thần tiên còn hoài hoài. Dạ khúc Anh sợ những cột đèn đổ xuống Rồi dây điện cuốn lấy chúng ta Bóp chết mọi hi vọng Nên anh dìu em đi xa Ði đi chúng ta đến công viên Nơi anh sẽ hôn em đắm đuối Ôi môi em như mật đắng Như móng sắc thương đau Ði đi anh đưa em vào quán rượu Có một chút Paris Ðể anh được làm thi sĩ Hay nửa đêm Hà Nội Anh là thằng điên khùng Ôm em trong tay mà đã nhớ em ngày sắp tới Chiếc kèn hát mãi than van Ðiệu nhạc gầy níu nhau tuyệt vọng Sao tuổi trẻ quá buồn như con mắt giận dữ Sao tuổi trẻ quá buồn như bàn ghế không bầy Thôi em hãy đứng dậy người bán hàng đã ngủ sau quầy anh đưa em đi trốn những giày vò ngày mai Bao giờ

Vứt

mẩu thuốc cuối cùng xuống giòng sông Con

thuyền xuôi Ai

xui rằng mùa măng chưa tới Muốn

làm người học trò mười bẩy tuổi Bông

mía trắng những căn nhà ngủ dưới cây Trời

xẫm Nếu

đã đi từ Hà Nội xuống Hải Phòng Như

kẻ say rót rượu lấy mà uống Thanh

Tâm Tuyền Liên

Đêm Mặt Trời Tìm Thấy ON A ROSE To Tadeusz Chrzanowski 1

Sweetness bears a flower's name- Spherical gardens tremble suspended over the earth

a sigh turns its head away I wind's face at the fence grass is spread out below the season of anticipation the coming will snuff out odors it will open colors the trees build a cupola of green tranquility the rose is calling you a blown butterfly pines after you threads burst instant follows instant O rosebud green larva unfold Sweetness bears the name: rose an explosion- purple's standardbearers emerge from the interior and the countless ranks trumpeters of fragrance on a long butterfly-horns proclaim the fulfillment 2 The intricate coronations cloister gardens orisons gold-packed ceremonies and flaming candlesticks triple towers of silence light rays broken on high the depths- O source of heaven on earth O constellations of petals …. do not ask what a rose is A bird may render it to you fragrance kills thought a light brushing erases a face O color of desire O color of weeping lids heavy round sweetness redness torn to the heart 3 a rose bows its head as if it had shoulders leans against the wind the wind goes off alone it cannot speak the word it cannot speak the word the more the rose dies the harder to say: rose Zbigniew Herbert: The Collected Poems 1956-1998 RHYTHMS OF THE SOUL:

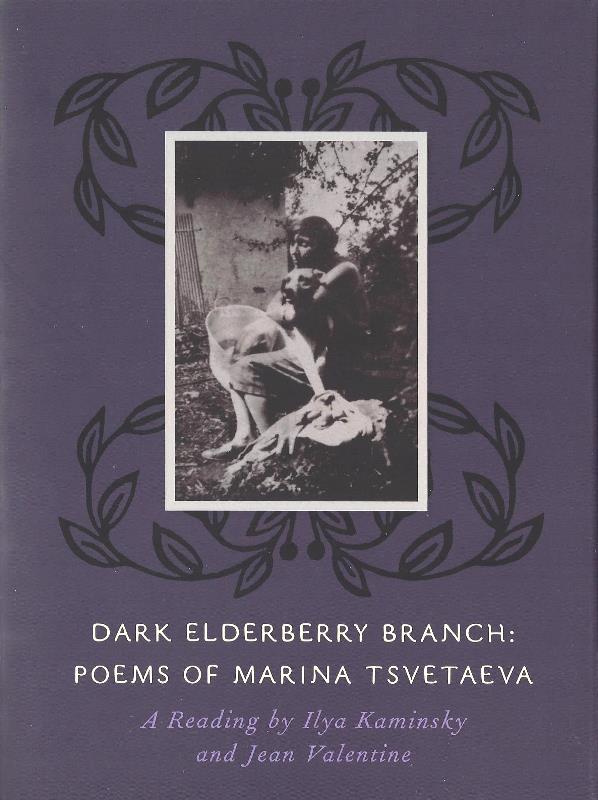

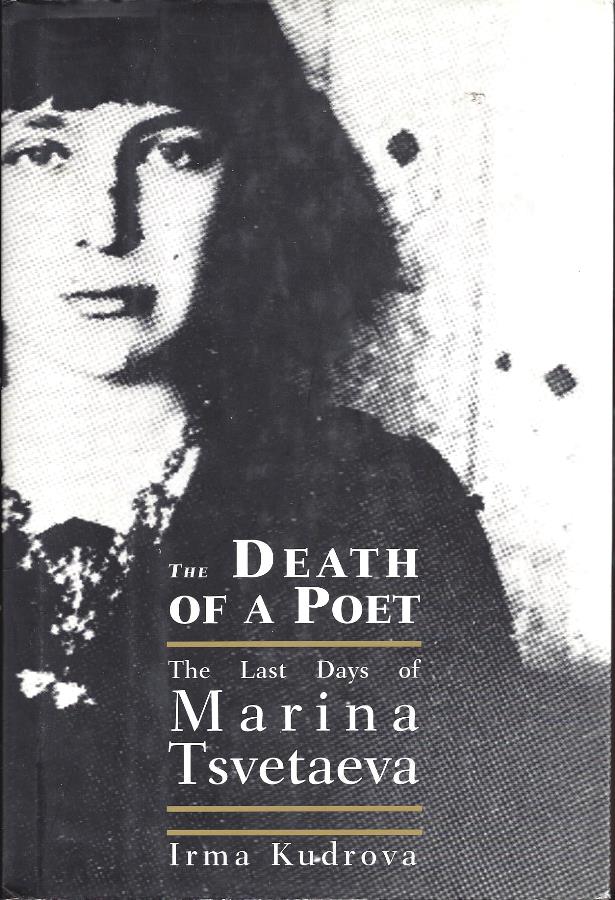

MARINA TSVETAEVA There are many souls in me, Marina Tsvetaeva once wrote, and readers of her work often have the feeling that spiritual forces compete in every line she ever wrote. The emotional intensity of her writing, whether in prose or in poetry, seems startlingly able to bend her language into unimaginable new shapes. That linguistic fearlessness makes her a challenge for translators, but readers of this volume will palpably sense the sheer force of her language. In choosing and ordering these writings, IIya Kaminsky and Jean Valentine create force fields across the poems and prose fragments; they have lifted a small number of texts from the massive Tsvetaeva legacy, creating luminous new versions for us to behold. The translations attain a kind of light-showered clarity before our eyes, with each scrap of text commanding our focused attention as if nothing else mattered. Tsvetaeva left a stunning amount of work for such a short and trouble-filled life. Born in 1892 into a musical and intellectual family, reared in an atmosphere where art must always have seemed her destiny, she was as fierce in her emotional attachments as she was in her quests for artistic expression. She married young, to Sergei Efron, and although her life would include affairs of searing passion and high drama, she loved Efron to the end. She followed him to Europe in emigration in 1922 and then back to the Soviet Union in 1939. Her return was a dreadful choice, but there were not a lot of good alternatives in Europe in those years. Efron was arrested in Moscow and executed; their daughter, Ariadna, who had been jailed earlier in the 1930s, was rearrested and sent to the camps. Their son Mur was soon killed in the Second World War. Tsvetaeva herself would die in 1941, in evacuation and by her own hand. Her sister, Anastasia, who survived until the 1990s, was not spared her share of suffering (including two terms in the labor camps). But because of Anastasia Tsvetaeva's efforts and those of Ariadna Efron, we have Tsvetaeva's manuscripts, including a treasure trove of notebooks and drafts. Some of the most startling pages in this volume come from those notebooks, or, as they are called here, daybooks. These sentences read as if direct transcriptions of the insights and recognitions that make writing possible. They allow readers in English to glimpse something of Tsvetaeva's creative laboratory. You must write as if God is watching you, wrote Tsvetaeva in one of the fragments. And although her work has the electric charge of this ever-present sublime audience, many of her poems and most of her essays are in fact addressed to individuals to whom she was deeply connected. She felt profound poetic kinships with Pasternak and Rilke, and there were many poets among her addressees. There was the great Osip Mandelstam: their 1916 romance produced legendary poems by both of them. Her poems to him show Tsvetaeva both charming and charmed: Where does this tenderness come from? And what will I do with it? Young stranger, poet, in this city of strangers: you and your eyelashes - longer than anyone's. Those eyelashes appear in another poem, in which Tsvetaeva says to Mandelstam that he has the god of poetry within him. In that same year, 1916 (it was a year of phenomenal poetic output for her), Tsvetaeva wrote a cycle of poems to Alexander Blok, adored by so many poets of her era. She was fascinated by the poetic persona adopted by Blok, but her poems captured the linguistic magic of his poetry, which for her inheres even in his name. To say that name is to feel an icicle on the tongue, she wrote, evoking the bracing pleasure of saying his poems to oneself. In 1916 she wrote poems to Anna Akhmatova as well, Akhmatova who would later associate the "dark elderberry branch" with Tsvetaeva's own name. Not all of Tsvetaeva's acts of dedicated speech were to such worthy addressees-the long Poem of the End and its twin, Poem of the Mountain, were prompted by the breakup of a rather tawdry affair with Konstantin Rodzevich when Tsvetaeva was living in Prague in the 1920s, but the resulting verse was no less staggering than the 1916 cycles. By the 1930s, the poet was writing more prose than poetry (and readers may find much more of that prose, in the volumes A Captive Spirit, tr. J. Marin King, and Art in the Light of Conscience, tr. Angela Livingstone); as this book shows so well, the two forms of expression were remarkably close in spirit. Tsvetaeva finds ways to make prose words vibrate with the high frequencies more readily found in lyric poetry. When we read Tsvetaeva, the worlds of Moscow before the Revolution and during the Civil War, and of emigre Prague and Paris, are recreated. She makes these places, and the people she knew, come alive. But her work also lets readers sense the distinctive creative energy of her own psyche. We follow her emotions of love and jealousy, of loss and rebellion, and we experience as if alongside her the travails of writing and thinking, the refusals to swim on the current of human spines, as one of her poems to Czechoslovakia has it. One should not underestimate the clarity of mind that grounded Tsvetaeva's emotions, nor the firmness of spirit that sustained her through harsh times. In offering us their versions of Tsvetaeva's writings, Jean Valentine and Ilya Kaminsky describe their work as homage-and it is a fitting tribute to this most rare poet. -STEPHANIE SANDLER from Poems for Moscow

From my hands-take this city not made by hands, my strange, my beautiful brother. Take it, church by church-all forty times forty churches, and flying up the roofs, the small pigeons; and Spassky Gates-and gates, and gates- where the Orthodox take off their hats; and the Chapel of Stars-refuge chapel- where the floor is-polished by tears; take the circle of the five cathedrals, my coal, my soul; the domes wash us in their darkgold, and on your shoulders, from the red clouds, the Mother of God will drop her own thin coat, and you will rise, happened of wonderpowers -never ashamed you loved me. MARCH 31 1916 "I won't leave you!" Only God can say this-or a peasant with milk in Moscow, winter 1918. EARTHLY TRACES, 1919-20 My "I don't want to" is always "I cannot." In me there is no arbitrariness. "I cannot"-and meek eyes. EARTHLY TRACES, 1919-20 I bless our hands' daily labor

I bless our hands' daily labor, bless sleep every night. Bless night every night. And the coat, your coat, my coat, half dust, half holes. And I bless the peace in a stranger's house-the bread in a stranger's oven. 1918 I am happy living simply

I am happy living simply like a clock, or a calendar. Or a woman, thin, lost-as any creature. To know the spirit is my beloved. To arrive on earth-swift as a ray of light, or a look. To live as I write: spare-the way God asks me-and friends do not.

Marina Tsvetaeva (1892-1941)

Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva was born in Moscow.

Her mother was a gifted pianist, her father a classicist and

the founder of what is now the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. Like

Pasternak, Tsvetaeva was steeped from childhood in art and music.

In 1902 Tsvetaeva's mother contracted tuberculosis. In hope of a cure, the family spent most of the next four years abroad. For a while they lived near Genoa. Frequent moves led to Tsvetaeva learning Italian, French and German. Around this time she gave up the strict musical studies imposed on her by her mother, who died in 1906, and turned to poetry. Along with many other writers and artists, Tsvetaeva stayed during subsequent years in the Crimea, at the home in Koktebel of the legendarily hospitable Maximilian Voloshin. There she met the poet Sergey Efron, whom she married in 1912. After the October Revolution, Tsvetaeva remained in Moscow, even though Efron was fighting in the White Army. Tsvetaeva left her younger daughter Irina, aged three, in a state orphanage, hoping they would feed her better than she could herself, but Irina died of starvation. In May 1922 Tsvetaeva and her surviving daughter left Moscow for Berlin, where they were reunited with Efron. In August that year they moved to Prague, then in 1925 to Paris. Tsvetaeva remained devoted to Efron, despite her many affairs. The most significant of these were with Osip Mandelstam; with Sofia Parnok; and, in Prague, with Konstantin Rodzevich, who inspired her two great cycles of love poems, Poem of the Mountain and Poem of the End. During her fourteen years in Paris, Tsvetaeva grew increasingly isolated. She offended most of the emigre community by praising Mayakovsky; mistakenly branding her as pro-Soviet, the editors of the important journal The Latest News stopped publishing her work. Tsvetaeva had been a regular contributor and was supporting her family - her husband, their daughter Ariadna and her young son Georgy - through her literary earnings." Tsvetaeva's isolation became complete when, in 1937, it emerged that Efron had been working as a Soviet agent; not only had he recruited for the NKVD (the Soviet security service), but he had also been complicit in several murders. Though fiercely anti-Soviet herself, she had no choice but to follow her husband back to the Soviet Union; how much she knew about his work for the NKVD is uncertain. Despite the extreme Romanticism of many of her views, Tsvetaeva was always clear-headed about political matters. In May I9I7, while many writers were being seduced by what they heard as the music of the Revolution, she had written: You stepped from a stately cathedral onto the blare of the plazas ... - Freedom! - The Beautiful Lady of Russian grand dukes and marquises. A fateful choir's rehearsing - the liturgy still lies before us! - Freedom! - A street-walking floozy on the foolhardy breast of a soldier! (trans. Boris Dralyuk) And 'God Be With You!' a short poem from June I934, ends: 'Follow after Hitler, Stalin / uncover from the sprawling corpses / a star, or the hooks of a swastika. Tsvetaeva uses every linguistic register. She coins words and draws freely on vulgarisms and archaisms. Her work has more rhythmic energy even than Mayakovsky's. Her constant interrogation of words - of their sounds, meaning and origin - can make a reader feel that he or she is being taken into the very heart of the Russian language. Among her finest works are the collections Craft (I923) and After Russia (I928), and The Ratcatcher (I925), a lyrical-satirical version of the Pied Piper legend in which the Bolshevik rats come to resemble the German burghers they have ousted. Her translations include not only Russian versions of Goethe and Rilke, but also French versions of poems by Pushkin. She wrote diaries, literary criticism and verse dramas. Throughout much of I926 she kept up an intense correspondence with Rilke and Pasternak; these exchanges have been published in full. In a poem addressed to Pasternak a year earlier, she had written: Distances divide, exclude us. They've dis-welded and dis-glued us. Despatched, disposed of, dis-inclusion - they never knew that this meant fusion of elbow grease and inspiration. (trans. Peter Oram) In her last years Tsvetaeva, like Khodasevich - and like Pushkin and Lermontov - turned increasingly to prose, most of it as emotionally and intellectually charged as her poetry. Her essay 'Pushkin and Pugachov' is a masterpiece. She also wrote a long article about the artist Natalya Goncharova. Tsvetaeva returned to the Soviet Union in 1939. Unable to publish her own work, she translated two ballads about Robin Hood, poems by Lorca, Baudelaire's 'Le Voyage' and some two thousand lines of the Georgian poet Vazha-Pshavela. After the German invasion in 1941 both Efron and Ariadna were arrested. Efron was shot; Ariadna sent to the Gulag. Tsvetaeva was evacuated from Moscow, but she then hanged herself in the town of Yelabuga; she may have been under pressure to act as an informer for the NKVD. No one attended her funeral. To Osip Mandelstam

Nothing's been taken away! We're apart -I'm delighted by this! Across the hundreds of miles that divide us, I send you my kiss. Our gifts, I know, are unequal. For the first time my voice is still. What, my young Derzhavin, do You make of my doggerel? For your terrible flight I baptize you - young eagle, it's time to take wing! You endured the sun without blinking, but my gaze - that's a different thing! None ever watched your departure more tenderly than this or more finally. Across hundreds of summers, I send you my kiss. MARINA TSVETAEVA (1916) Peter Oram Gửi Osip Mandelstam

Chẳng có gì bị lấy đi Đôi ta mỗi người mỗi ngả - Em sướng điên lên vì chuyện này! Qua ngàn dâu xanh biếc một màu, em gửi tới chàng 1 nụ hôn Tài năng thiên bẩm của đôi ta, thì không đồng đều Lần đầu tiên, tiếng nói của ta câm nín Hỡi anh yêu, tên tuổi trẻ Derzhavin của ta ơi Mi đã làm gì với những vần thơ tồi tệ của ta? Dành cho chuyến đi khủng khiếp của mi Tới đây, ta rửa tội cho – Con chim ưng trẻ, tới giờ cất cánh Hãy nhìn thẳng vào mặt trời, chịu đựng chuyến bay, không thèm nháy mắt Nhưng cái nhìn ban phước lành của ta cho mi, thì lại là chuyện khác Chẳng đứa khốn nào theo dõi mi lên đường Dịu dàng như thế này Sau chót như thế này Qua ngàn ngàn mặt trời, ánh nắng, mùa hè Ta gửi cho mi nụ hôn của ta from To Mayakovsky

[ ... ] Shot a bullet into his soul, as if it were his own enemy. The wrestler who wrestled God has destroyed another temple. [ ... ] He destroyed many temples, but none more precious than this. Give peace, O Lord, to the soul of this your deceased enemy. (1930) Robert Chandler [Từ] Gửi Mayakovsky

Chơi 1 phát đạn vào linh hồn anh taNhư thể đó là kẻ thù của riêng xừ luý Tên đô vật đô vật Chúa Đã huỷ diệt một ngôi đền khác Anh ta huỷ diệt rất nhiều đền Nhưng chẳng có cái nào quí bằng cái này Hãy ban bình an, Ôi Chúa, cho linh hồn Của kẻ thù đã ngỏm này của người To Mayakovsky

Beyond the chimneys and steeples, baptized by smoke and flame, stamping-footed archangel, down the decades I call your name! Rock-steady or change-at-a-whim! Coachman and stallion in one! He snorts and spits into his palm - chariot of glory, hold on! Singer of city-square wonders, I salute that arrogant tone that rejected the brilliant diamond for the sake of the ponderous stone. I salute you, cobblestone-thunderer! - see, he yawns, gives a wave, then he swings himself back into harness, back under : the shafts, his archangelic wings. (1921) Peter Oram The Penguin Book of Russian Poetry 17.

Having arrived abroad, Tsvetaeva wrote, "My motherland is any place with a writing desk, a window, and a tree by that window." She wrote of exile: "For lyric poets and fairy-tale authors, it is better that they see their motherland from afar-from a great distance." Compare this to Gogol: " ... my nature is the ability to imagine a world graphically only when I have moved far away from it. That is why I can write about Russia only in Rome. Only there does it stand before me in all its hugeness,"!' Again, Tsvetaeva: "Russia (the sound of the word) no longer exists, there exist four letters: USSR-I cannot and will not go where there are no vowels, into those whistling consonants. And, they won't let me there, the letters won't open." So Tsvetaeva spent seventeen years in France. France did not allow foreigners to have regular jobs and papers were hard to obtain. But Paris had a large concentration of journals, publishing houses, and emigre intellectuals. Tsvetaeva wrote, "1 get numerous invitations, but 1 cannot show myself because there is no silk dress, no stockings, no patent leather shoes, which is the local uniform. So 1 stay at home, accused from all sides of being too proud.'?" After Hitler assumed power in Germany, the USSR began to look brighter to many emigres. After much family drama (which we need not explore here), Tsvetaeva, without any particular nostalgic feeling, returned to Moscow on June 18,1939.

Tam giác tình thần thánh? Thứ tình yêu chỉ gồm có chiêm ngưỡng và kính trọng, thứ amour platonique mà anh nói đó cũng làm Hương sợ. It is the most beautiful law of our species that that which is not admired is forgotten. [Luật đẹp nhất của con người là, đàn bà thì là đẹp, và đẹp, thì là để chiêm ngưỡng, và chẳng hề bị lãng quên]. Alain Đó là luật đẹp nhất của giống người, là, cái gì không được chiêm ngưỡng, thì bèn vứt vô sọt rác. The linguistic density of her poems can be compared to that of Gerald Manley Hopkins, except that she has many more voices. In a letter to Rilke, with whom she had an epistolary romance, she writes: I am not a Russian poet and am always astonished to be taken for one and looked upon in this light. The reason one becomes a poet (if it were even possible to become one, if one were not one before all else!) is to avoid being French, Russian, etc., in order to be everything. Charles Simic: Tsvetaeva, The Tragic Life Độ đậm đặc ngôn ngữ trong thơ của bà có thể so với của GMH, ngoại trừ điều này, bà có nhiều giọng. Trong thư gửi Rilke, người tình 1 thuở, bà viết: Tôi không phải là nhà thơ Nga, và luôn ngạc nhiên khi bị nhìn như thế. Lý do để một con người trở thành thi sĩ (nếu có thể như thế, trước tất cả bất cứ cái gì khác) là để tránh là 1 tên Tẩy, tên Nga, tên Mít... để là tất cả NINA ZIVANCEVIC [1957-] Zivancevic was born in Belgrade. She is a literary critic, journalist, and translator as well as a poet. She lived for several years in New York, where she wrote in English, and now resides in Paris. New Rivers Press published a book of her poems, More or Less Urgent, in 1980. The poems in this anthology come from her books The Spirit of Renaissance (1989) and At the End of the Century (2006). Charles Simic: The Horse Has Six Legs, an anthology of Serbian Poetry Zivancevic sinh tại Belgrade. Bà là phê bình gia, ký giả, dịch giả và nhà thơ. Sống vài năm ở New York; ở đó, bà viết bằng tiếng Anh, và hiện định cư ở Paris. Nhà New Rivers Press đã xb một cuốn thơ của bà, Khẩn cấp, ít hay nhiều, 1980. Mấy bài thơ ở đây, là từ những cuốn Tinh Thần Phục Hưng, và Ở Vào Cuối Thế Kỷ. Letter to Tsvetaeva

Ah, now our time has come, Marina. You visit me at night while I sit alone with a glass of wine in hand -you who do not need a key- for you the most secret door of my room is always open: abandoned by our mothers, we both loved children and poetry, and hated Paris and poverty, wearing the one and only dirty dress, we kept clear of landlords and cops. We both had blue eyes, many lovers, and the incapacity to live with anyone. Ah, I almost forgot: our fathers, too, had similar jobs-they occupied themselves with museums and art ... Still, I got angry yesterday when someone called me Marina ... I'm neither important nor odd enough to send daily reports to Beria ... How furious I was that you hanged yourself! What courage, what a double cross, what a lie, what a betrayal of poetry ... Marina, I'm a child as you can see, about you and life I really know nothing. Thư gửi Tsvetaeva Hà, hà, thời của chúng mình tới rồi, Marina Bạn viếng thăm tớ vào ban đêm, khi tớ ngồi một mình Với ly rượu chát trong tay Bạn đâu cần chìa khoá Với bạn, thì cái cửa bí mật nhất phòng tớ Luôn luôn mở: Bị má của chúng mình bỏ rơi Cả hai đều yêu con nít và thơ ca Ghét Paris và sự nghèo khổ Mặc cái áo, độc nhất chỉ có nó, dơ dáy Tránh chủ nhà và cớm Cả hai đều mắt xanh, có nhiều người yêu Và cùng không làm sao sống được với bất cứ thằng nào Ôi, xém quên, cha của chúng ta Thì đều có việc làm như nhau Loay hoay, hì hục với viện bảo tàng và nghệ thuật... Tuy thế, hôm qua, tớ tức điên lên được Khi có kẻ gọi tớ là Marina... Tớ thì không thấy mình quan trọng, và kỳ cục đến nỗi Hàng ngày gửi báo cáo cho Beria Bạn đâu biết tớ giận dữ đến như thế nào Khi biết bạn tự treo cổ! Can đảm làm sao, lừa lọc làm sao, dối trá làm sao Phản bội thơ ca đến như thế, là sao? Marina, bạn thấy đấy, tớ là đứa con nít Về bạn, và về đời Tớ chẳng biết gì. Tứ Tấu Khúc

Je t'aime parce que tu veux l'impossible. Ta thương mi bởi vì mi muốn

điều không thể. BHD Bất giác,

lại nhớ đến bạn C., một trong Thất Hiền. C. nhận xét, mỗi lời nói của BHD

với bạn Gấu ta, đúng là một sấm ngôn! Quả có thế! Chỉ một sấm ngôn, của BHD, mà

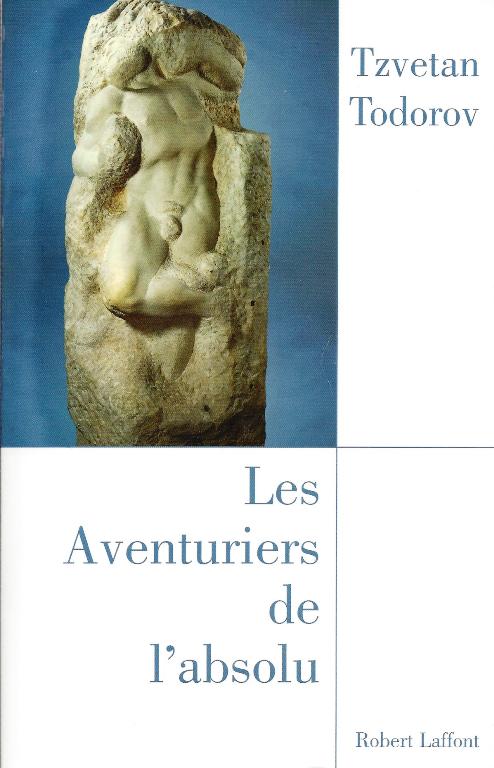

Tzvetan Todorov viết cả một cuốn sách về nó: Những kẻ phiêu lưu đi tìm Tuyệt

Đối, Les Aventuriers de l’absolu.

Trong hàng bao thiên niên kỷ,

nhân loại gọi tuyệt đối bằng cái tên BHD!

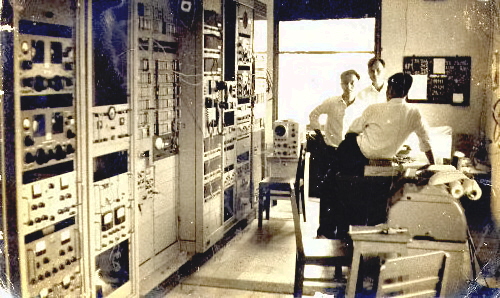

Gấu đứng chống nạnh, trên đỉnh

tòa building số 5 Phan Đình Phùng, cc 1963 Gấu đứng chống nạnh. Người ngồi

quay lưng lại, là Trần Bảo Thạch, trưởng đài VTĐ thoại quốc tế, số 5 Phan

Đình Phùng, Sài Gòn. Nơi tôi làm việc là tầng lầu

trên cùng một building, bất động sản của người Pháp; tôi là chuyên viên

kỹ thuật lo sửa chữa máy móc, trông coi đường dây liên lạc vô tuyến điện

thoại, viễn ký, viễn ảnh từ Sài Gòn tới những thành phố lớn, thủ đô các

quốc gia trên thế giới. Do hoàn cảnh địa dư, buổi sáng tôi có thể chào buổi

chiều, "Good Evening", với một đồng nghiệp ở California; nếu rảnh rang,

tôi có thể hỏi thăm hoặc bông đùa đôi câu với một nữ điện thoại viên ở Hongkong,

hoặc Tokyo… Buổi chiều, tôi có thể biết thời tiết một Paris buổi sáng;

tôi hỏi thăm những đồng nghiệp không bao giờ gặp mặt, có phải tuyết bắt

đầu rơi, mùa đông ở nơi xa xôi đó có gì tương tự với những ngày giá lạnh

của miền quê hương cũ… Những ngày ở Sài Gòn (1965) Sờ Vô Cái Đẹp: Những kẻ Phiêu Lưu Đi Tìm

Tuyệt Đối

Trong hàng thiên niên kỷ,

tuyệt đối có tên là Thượng Đế. Sau Cách Mạng Pháp, tuyệt đối được lôi

xuống mặt đất, ban cho cái tên Quốc Gia, rồi, Giai Cấp, Dòng Giống, Race. Mở ra Trăm Năm Cô Đơn, là cảnh nhân vật

chính đứng trước đội hành quyết, và, vào những giây phút cuối cùng của đời

mình, đột nhiên nhớ ra cái cảm giác lạnh buốt khi, lần đầu, còn là một đứa

con nít ở cái làng hẻo lánh ở một xó xỉnh nào đó trên trái đất, làng Macondo,

thằng bé được sờ tay vào một cục nước đá.

Sờ vô cái đẹp. Todorov, trong Những Kẻ Phiêu Lưu Tìm Tuyệt Đối, thay vì sờ vô nỗi chết, ông tả cái cảm giác tuyệt vời, sờ vô cái đẹp. Trong lời tựa cuốn sách, ông kể, buổi tối hôm đó, ông cùng người bạn đi dự một buổi hoà nhạc. Dàn nhạc "Le Concerto Italiano", Rinaldo Alessandri điều khiển, chơi nhạc Vivaldi, tại nhà hát Champs-Élysées, Paris. Như thường lệ, ông thấy mình thật khó tập trung, cứ suy nghĩ vơ vẩn đâu đâu. Khán thính giả đầy rạp... Bất thình lình, một điều gì đó xẩy ra. Dàn nhạc nhỏ, chỉ đàn dây và sáo, tấn công khúc nhạc nổi tiếng la Notte. Bản nhạc được chơi với một độ chính xác tuyệt hảo... đến nỗi, chỉ cần một vài giây là cả phòng chết sững, mọi người đều nín thở. Tất cả đều có cảm giác, họ đang được những nghệ sĩ dẫn vào một biến cố lạ lùng, một kinh nghiệm để đời. Tôi như nổi da gà, ông viết. Và khi tiếng nhạc chấm dứt, sau một vài giây im lặng, cả rạp vỡ òa tiếng vỗ tay. Làm sao giải thích kinh nghiệm? Vivaldi là một nhạc sĩ bậc thầy, đúng, dàn nhạc tuy nhỏ, nhưng thuộc loại chiến số một, đúng, nhưng đâu chỉ có vậy? Ông cố tìm cách giải đáp. [Xin để hồi sau phân giải]. NINA ZIVANCEVIC [1957-] Zivancevic was born in Belgrade. She is a literary critic, journalist, and translator as well as a poet. She lived for several years in New York, where she wrote in English, and now resides in Paris. New Rivers Press published a book of her poems, More or Less Urgent, in 1980. The poems in this anthology come from her books The Spirit of Renaissance (1989) and At the End of the Century (2006). Charles Simic: The Horse Has Six Legs, an anthology of Serbian Poetry Letter to Tsvetaeva

Ah, now our time has come, Marina. You visit me at night while I sit alone with a glass of wine in hand -you who do not need a key- for you the most secret door of my room is always open: abandoned by our mothers, we both loved children and poetry, and hated Paris and poverty, wearing the one and only dirty dress, we kept clear oflandlords and cops. We both had blue eyes, many lovers, and the incapacity to live with anyone. Ah, I almost forgot: our fathers, too, had similar jobs-they occupied themselves with museums and art ... Still, I got angry yesterday when someone called me Marina ... I'm neither important nor odd enough to send daily reports to Beria ... How furious I was that you hanged yourself! What courage, what a double cross, what a lie, what a betrayal of poetry ... Marina, I'm a child as you can see, about you and life I really know nothing. Ode to Western Wind

O, great great Western wind, lift me up and take me back to people and places I loved, save me from this neoclassical order and its stupidities, take me as far as you can from Gard du Nord from which they took 200,000 Jews to camps, so that not a single one came back, carry me away from Europe poisoned with wars and plagues, as far as possible from the United States where people die in hunger and ignorance, take me back to Serinda where to breathe is more important than sublime thought and moving about, take me to the make-believe land of poetry and keen spirit where women don't speak of equality and where men dance the tango all day and all night, lift me high, wind and make me forget this terrible ever-present reality, since, if the spring has indeed come why am I trotting so far behind it?

Tam giác tình thần thánh? Thứ tình yêu chỉ gồm có chiêm ngưỡng và kính trọng, thứ amour platonique mà anh nói đó cũng làm Hương sợ. It is the most beautiful law of our species that that which is not admired is forgotten. [Luật đẹp nhất của con người là, đàn bà thì là đẹp, và đẹp, thì là để chiêm ngưỡng, và chẳng hề bị lãng quên]. Alain Đó là luật đẹp nhất của giống người, là, cái gì không được chiêm ngưỡng, thì bèn vứt vô sọt rác.

from Poems for

Moscow

Seven hills-like seven bells,

seven bells toll in the seven bell towers.

All forty times forty churches, all seven hills of bells, everyone of them counted, like pillows. I was born in the ringing of bells on the saint's day of John the Theologian. Over the wattle fence, our gingerbread house- dropped its crumbs for Saint John the Theologian. I loved it first: the first ringing- the nuns sweeping to mass in the warmth of sleep- the crack of the fire catching in the stove- seven bells, seven bell towers. Come with me, people of Moscow, you crazy, looting, flagellant mob! And priest-place on my tongue all of Moscow, the city of bells! Marina Tsvetaeva Thơ cho Moscow

Bẩy đồi – như bẩy chuôngBẩy chuông ngân trong bẩy tháp chuông Tất cả bốn mươi lần bốn mươi nhà thờ, tất cả bẩy đồi Chuông, mọi cái, đếm, như những cái gối Tôi sinh ra trong tiếng chuông ngân Vào ngày thánh John nhà Thần Luận Trên hàng cọc, căn nhà bánh gừng của chúng tôi Nhả những miểng vụn cho Thánh John nhà Thần Luận Tôi yêu nó, thoạt đầu: tiếng chuông thứ nhất Những nữ tu cuộn vào lễ thánh trong cái ấm áp của giấc ngủ Tiếng lửa lách tách trong lò Bẩy chuông bẩy tháp chuông Đến với tôi, cư dân Moscow Đám khùng điên ăn cướp ăn trộm du thử du thực đáng đánh đòn! Và tu sĩ - để trên lưỡi tôi Tất cả Moscow, thành phố của những cái chuông. Admiring her, the poet Balmont once said, "You demand from poetry what only music can give." Was she a 'difficult' poet? Perhaps. But first we must clarify what 'difficult' meant for that country and that time. To clarify this, one turns to Pushkin, the father of the Russian poetic tradition: One of our poets used to say proudly, "Though some of my verses may be obscure they are never prosaic." There are two kinds of obscurity; one arises from a lack of feelings and thoughts, which have been replaced by words; the other from an abundance of feelings and thoughts, and the inadequacy of words to express them. Bạt Ngưỡng mộ nhà thơ, thi sĩ Balmond có lần phán, “Bà đòi thơ ca, cái chỉ âm nhạc có thể cho.” Bà là nhà thơ "khó khăn ". Có lẽ. Nhưng trước hết chúng ta phải làm sáng tỏ "khó" nghĩa là gì, với xứ sở đó, thời kỳ đó. Và để làm sáng tỏ, người ta phải viện tới Pushkin, người cha của truyền thống thơ Nga. Một trong những nhà thơ của chúng thường hãnh diện phán, “Mặc dù một vài câu thơ của tôi có thể tối tăm, chúng không bao giờ là văn xuôi”. Có hai thứ tối tăm, một dấy lên từ cái sự thiếu cảm nghĩ, tư tưởng, và được thay thế bằng từ ngữ; một, từ sự thừa mứa cảm nghĩ và tư tưởng, và thiếu từ để diễn tả chúng. There are four of us

On paths of air I seem to overhear

two friends, two voices, talking in their turn, Did I say two? ... There by the eastern wall, where criss-cross shoots of brambles trail, -O look!- that fresh dark elderberry branch is like a letter from Marina in the mail. -ANNA AKHMATOVA NOVEMBER 1961 (IN DELIRIUM) from Poems of Akhmatova, tr. Stanley Kunitz and Max Hayward. Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1973. from Poems

for Blok

Your name is a-bird in my hand,

a piece of ice on my tongue.

The lips' quick opening. Your name-four letters. A ball caught in flight, a silver bell in my mouth. A stone thrown into a silent lake is-the sound of your name. The light click of hooves at night -your name. Your name at my temple -sharp click of a cocked gun. Your name-impossible- kiss on my eyes, the chill of closed eyelids. Your name-a kiss of snow. Blue gulp of icy spring water. With your name-sleep deepens. APRIL 15 1916 [Từ] Thơ cho Blok

Tên của mi – con chim trong tay taLát băng trên lưỡi Hé môi thật lẹ Tên mi - bốn chữ Trái banh bị tóm trên đường bay Chuông bạc trong miệng Hòn đá ném xuống hồ lặng Là tên mi dội vào tai ta Tiếng ợ nhẹ trong đêm Tên mi trong miếu đền của ta Tiếng click nhọn hoắt của cây súng hếch lên 1 phát Thèm nhả đạn Tên mi – không thể Nụ hôn lên mắt Cú rùng mình khép mi Tên mi, nụ hôn của tuyết Ngụm nước mùa xuân giá lạnh, xanh xanh Với tên mi Ta chìm sâu vào giấc ngủ Tháng Tư, 15, 1916 from Poem of the End

Outside of town! Understand? Out!

We're outside the walls. Outside life- where life shambles to lepers. The Jew-ish quarter. It's a hundred times an honor to stand with the Jews- for anyone not scum. Outside the walls, we stand. Outside life- the Jew-ish quarter. Life is for converts only! Judases of all faiths. Go find a leper colony! Or hell! Anywhere-just not life-life loves only liars, lifts its sheep to blades. I stomp on my birth certificate, rub out my name! Go find a leper colony! With David's star, I stand- I spit on my passport. And back in the town they're saying, It's only right- the Jews don't want to live! Ghetto of the chosen! The wall and ditch. No mercy. In this most Christian of worlds all poets-are Jews. PRAGUE, 1924 For complete concurrence of souls there needs to be a concurrence of breath, for what is breath, if not the rhythm of the soul? So, for humans to understand one another, they must walk or lie side by side. ON LOVE, 1917 AFTERWORD

"There cannot be too much of lyric because

lyric itself is too much."

-TSVETAEVA 1.

As a child, Marina Tsvetaeva had "a frenzied

wish to become lost" in the city of Moscow. As a girl,

she dreamed of being adopted by the devil in Moscow streets,

of being the devil's little orphan. But Russian poetry began

in St. Petersburg-the new capital was founded in the early eighteenth

century. Moscow was the old capital, devoid of literature.

No literature existed in Russia before St. Petersburg's cosmopolitan

streets.

But St. Petersburg was also, for two hundred years, the least free city in Russia. It was dominated by the secret police, watched by the Tsar, and full of soldiers and civil servants-the city of loneliness Dostoevsky and Gogol shared with us. Moscow was for a long time the seat of the old Russia that considered St. Petersburg blasphemous. Moscow was the center of Russia without professors, without foreigners; it was the Russia where the Tsar was still thought to be divine. Peter the Great's unloved first wife, speaking from Moscow, put a curse on St. Petersburg, saying that it would "stand empty." In the middle of this Moscow, Marina Tsvetaeva wanted a desk. Khi còn bé, Tsvetaeva có một ước muốn khùng điên ba trợn, là biến mất, thất lạc, mất mát, tuyệt tích giang hồ, bị mẹ mìn bắt, trở thành bỏ đi: to become lost, ở trong thành phố Moscow. Khi là 1 thiếu nữ, cô mơ được quỉ nhận trong đường phố Moscow, là một đứa trẻ mồ côi của quỉ. Nhưng thơ ca Nga bắt đầu ở St. Petersburg – “tân thủ đô” được xây dựng vào đầu thế kỷ 18. Moscow là “cựu thủ đô”, đếch có văn chương [THNM, bèn nghĩ đến Hà Lội, nhưng đây chính là ý của Brodsky về trung tâm và ngoại vi]. Văn chương Nga không có, trước khi có những con phố bốn phương trời mười phương đất - tạm dịch cụm từ “cosmopolitan streets” - của St. Petersburg. 2. For her, a desk was the first and only musical instrument.' Tsvetaeva said her first language was not Russian speech; it was music. Her first word, spoken at the age of one, was "ganuna" or "scale?" But music was difficult. "You press on a key on a piano," she said remembering her childhood. "A key is right there, here, black or white, but a note? ... But one day I saw instead of notes sitting on the staff, there were-sparrows! Then I realized that musical notes live on branches, each one on its own, and from there they jump onto the keys, each one onto its own. And then-it sounds. When I stop playing music the notes return on the branches-as birds go to sleep." Marina Tsvetaeva's mother was a talented musician. But when Marina was still very young, her mother was already ill. The illness made them travel from one city to another, from one country to the next. On the road, Marina Tsvetaeva learned German, Italian, then French. She wrote poems in French as well as German; her grandfather recited German poetry by heart. Her mother's illness was a carriage which took her, for years, across Europe. But her mother wanted to die at home, in Russia. So in 1906, mother and daughter Tsvetaeva started for Moscow. Her mother died on the road, not reaching the city. Tsvetaeva was 14. 6. A few years after her mother's death, Marina Tsvetaeva, still a young schoolgirl, published her first book. Critics praised the book's uncommon "intimacy of tone" and its structure, called it a lyric diary, a daybook, a sequence;" they praised the "bravery" of this "intimacy." There was also criticism. Brusov, the venerable older poet, encouraged her poems' "sense of intimacy" but noted that this lyric intimacy was, sometimes-of ten-too much. But there cannot be "too much" of lyric because lyric itself is "too much." Tsvetaeva: "A lyric poem is a created and instantly destroyed world. How many poems are in the book-that many explosions, fires, eruptions: EMPTY spaces. The lyric poem-is a catastrophe. It barely began-and already ended.?" Vài năm sau, khi bà mẹ mất, còn là 1 nữ sinh, Marina Tsvetaeva đã cho xb cuốn sách đầu tay. Phê bình gia khen, giọng riêng tư chẳng giống ai, đây là 1 thứ nhật ký vãi lệ, sự can đảm của cái riêng tư thầm kín. Bruso, một nhà thơ đáng kính, già, khuyến khích thơ của cô bé, ở "cảm quan tâm tư thầm kín riêng tư" của nó, và ghi nhận, hình như hơi bị quá riêng tư, thầm kín, đôi lúc. Nhưng làm gì có “quá” vãi lệ, bởi vì vãi lệ, chính nó, là đã “quá quá” rồi. Tsvetaeva phán: Một bài thơ vãi lệ là một thế giới, được sáng tạo và liền lập tức, bị huỷ diệt. Có bao nhiêu bài thơ trong 1 cuốn sách – là bấy nhiêu nổ tung, lửa cháy, phún thạch: những không gian TRỐNG RỖNG. Thơ trữ tình là 1 thảm họa. Nó chưa kịp bắt đầu, thì đã ngỏm củ tỏi rồi. Đúng là cú đâm trúng tử huyệt thơ Mít. Chúng, thi sĩ Mít, chỉ làm được thứ thơ này, để tán gái, và thơ ngồi bên ly cà phê nhớ bạn hiền, để tán bạn, sự thực, để tán chính chúng! Ta nâng niu một nhánh u thảo:

Thơ Marina Tsvetaeva AFTERWORD

"There cannot be too much of lyric because

lyric itself is too much."

-TSVETAEVA 1.

As a child, Marina Tsvetaeva had "a frenzied wish to become

lost" in the city of Moscow. As a girl, she dreamed of being adopted

by the devil in Moscow streets, of being the devil's little orphan. But

Russian poetry began in St. Petersburg-the new capital was founded in the

early eighteenth century. Moscow was the old capital, devoid of literature.

No literature existed in Russia before St. Petersburg's cosmopolitan streets.

But St. Petersburg was also, for two hundred years, the least free city in Russia. It was dominated by the secret police, watched by the Tsar, and full of soldiers and civil servants-the city of loneliness Dostoevsky and Gogol shared with us. Moscow was for a long time the seat of the old Russia that considered A kiss on the forehead

A kiss on the forehead-erases misery. I kiss your forehead. A kiss on the eyes-lifts sleeplessness. I kiss your eyes. A kiss on the lips-is a drink of water. I kiss your lips. A kiss on the forehead-erases memory. Hôn 1 phát lên trán

Hôn 1 phát lên trán - xóa sạch khốn cùngGấu bèn hôn trán em Hôn 1 phát lên mắt - nhấc đi cơn mất ngủ Gấu bèn hôn mắt em Hôn 1 phát lên môi - chiêu ngụm nước Gấu bèn hôn môi em Hôn 1 phát lên trán - xóa sạch hồi ức |