phụ trách Giới thiệu Kertesz Nobek 2002 [1] Giới thiệu Kertesz Nobel 2002 [2] Ngôn Ngữ Lưu Vong Quyền tự do xác định tự thân [Ngôn ngữ lưu vong] Bản Tiếng Anh Diễn Văn Nobel 2002 1 NQT dịch 2 NTV dịch Kertesz trả lời tờ Le Point. Kertesz trả lời tờ Lire Kertesz trả lời Le Monde Tiểu Thuyết Trinh Thám Kertesz trả lời Le Figaro/AFP, 8.2.2006 Không số kiếp |

Imre Kertész obituary

1929-2016 http://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/31/imre-kertesz-obituary Và sự phục sinh không dứt của sự thiện, chứ không phải của sự dữ và độc ác, cho chúng ta thấy chân lý về thế giới và cuộc đời của chúng ta. Nhà văn Do Thái-Hungari, Imre Kertesz, đã đoạt giải Nobel Văn học năm 2002, đã có một chứng tá thâm thúy về điều này. Ông từng là một cậu bé trong trại giết người của Đức Quốc xã, nhưng điều ông nhớ nhất về quãng thời gian này, không phải là những bất công, tàn ác, và cái chết mà ông chứng kiến ở đó, nhưng là những hành động nhân ái, trìu mến và vị tha giữa sự dữ. Vì thế sau chiến tranh, ông mong muốn đọc hạnh các thánh hơn là tiểu sử các tội phạm chiến tranh. Vẻ ngoài của sự thiện lôi cuốn ông. Với ông, có thể hiểu được sự dữ, còn sự thiện thì sao? Ai có thể giải thích được? Nguồn cội sự thiện là gì? Tại sao sự thiện cứ tuôn ra, tuôn tràn trở lại trên khắp cõi trái đất, trong mọi tình trạng thế nào chăng nữa? http://ronrolheiser.com/the-triumph-of-goodness/#.Vv8aYjZzY5s And it is this, the constant resurrection of goodness, not that of viciousness and evil, which speaks the deepest truth about our world and our lives. The Jewish-Hungarian writer, Imre Kertesz, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2002, gives a poignant testimony of this. He had as a young boy been in a Nazi death camp, but what he remembered most afterwards from this experience was not the injustice, cruelty, and death that he saw there, but rather some acts of goodness, kindness, and altruism he witnessed amidst that evil. After the war, it left him wanting to read the lives of saints rather than biographies of war. The appearance of goodness fascinated him. To his mind, evil is explicable, but goodness? Who can explain it? What is its source? Why does it spring up over and over again all over the earth, and in every kind of situation? It springs up everywhere because God’s goodness and power lie at the source of all being and life. This is what is revealed in the resurrection of Jesus. What the resurrection reveals is that the ultimate source of all that is, of all being and life, is gracious, good, and loving. Moreover it also reveals that graciousness, goodness, and love are the ultimate power inside reality. They will have the final word and they will never be captured, derailed, killed, or ultimately ignored. They will break through, ceaselessly, forever. In the end, too, as Imre Kertesz suggests, they are more fascinating than evil. The Triumph of Goodness March 28, 2016 The stone which rolled away from the tomb of Jesus continues to roll away from every sort of grave. Goodness cannot be held, captured, or put to death. It evades its pursuers, escapes capture, slips away, hides out, even leaves the churches sometimes, but forever rises, again and again, all over the world. Such is the meaning of the resurrection. Goodness cannot be captured or killed. We see this already in the earthly life of Jesus. There are a number of passages in the Gospels which give the impression that Jesus was somehow highly elusive and difficult to capture. It seems that until Jesus consents to his own capture, nobody can lay a hand on him. We see this played out a number of times: Early on in his ministry, when his own townsfolk get upset with his message and lead him to the brow of a hill to hurl him to his death, we are told that “he slipped through the crowd and went away.” Later when the authorities try to arrest him we are told simply that “he slipped away”. And, in yet another incident when he is in temple area and they try to arrest him, the text simply says that he left the temple area and “no one laid a hand upon him because his hour had not yet come.” Why the inability to take him captive? Was Jesus so physically adept and elusive that no one could imprison him? These stories of his “slipping away” are highly symbolic. The lesson is not that Jesus was physically deft and elusive, but rather that the word of God, the grace of God, the goodness of God, and power of God can never be captured, held captive, or ultimately killed. They are adept. They can never be held captive, can never be killed, and even when seemingly they are killed, the stone that entombs them always eventually rolls back and releases them. Goodness continues to resurrect from every sort of grave. And it is this, the constant resurrection of goodness, not that of viciousness and evil, which speaks the deepest truth about our world and our lives. The Jewish-Hungarian writer, Imre Kertesz, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2002, gives a poignant testimony of this. He had as a young boy been in a Nazi death camp, but what he remembered most afterwards from this experience was not the injustice, cruelty, and death that he saw there, but rather some acts of goodness, kindness, and altruism he witnessed amidst that evil. After the war, it left him wanting to read the lives of saints rather than biographies of war. The appearance of goodness fascinated him. To his mind, evil is explicable, but goodness? Who can explain it? What is its source? Why does it spring up over and over again all over the earth, and in every kind of situation? It springs up everywhere because God’s goodness and power lie at the source of all being and life. This is what is revealed in the resurrection of Jesus. What the resurrection reveals is that the ultimate source of all that is, of all being and life, is gracious, good, and loving. Moreover it also reveals that graciousness, goodness, and love are the ultimate power inside reality. They will have the final word and they will never be captured, derailed, killed, or ultimately ignored. They will break through, ceaselessly, forever. In the end, too, as Imre Kertesz suggests, they are more fascinating than evil. And so we are in safe hands. No matter how bad the news on a given day, no matter how threatened our lives are on a given day, no matter how intimidating the neighborhood or global bully, not matter how unjust and cruel a situation, and no matter how omnipotent are anger and hatred, love and goodness will reappear and ultimately triumph. Jesus taught that the source of all life and being is benign and loving. He promised too that our end will be benign and loving. In the resurrection of Jesus, God showed that God has the power to deliver on that promise. Goodness and love will triumph! The ending of our story, both that of our world and that of our individual lives, is already written – and it is a happy ending! We are already saved. Goodness is guaranteed. Kindness will meet us. We only need to live in the face of that wonderful truth. They couldn’t arrest Jesus, until he himself allowed it. They put his dead body in a tomb and sealed it with a stone, but the stone rolled away. His disciples abandoned him in his trials, but they eventually returned more committed than ever. They persecuted and killed his first disciples, but that only served to spread his message. The churches have been unfaithful sometimes, but God just slipped away from those particular temple precincts. God has been declared dead countless time, but yet a billion people just celebrated Easter. Goodness cannot be killed. Believe it! Tks. NQT Trong bài ai điếu trên Guardian, viết: Tác phẩm của K. đôi khi ló ra cái hàm hồ của ông, về tín ngưỡng, khiến đôi khi ông không tin có Thượng Đế. Trong tác phẩm Gályanapló, ông đi 1 đường nghịch thiên, ngược ngạo: Thượng Đế có ở Lò Thiêu. Người ném tôi vô đó, để kể (“bao giờ thì tôi có thể “lại viết”, của TTT, là ở chỗ này) lại cho Người nghe, Người đã làm gì ở đó! Kertész’s books also sometimes betrayed his ambivalent relationship with religion, which at times led him to doubt the existence of God. In his work Gályanapló (Galley Boat-Log, 1992) he chose a paradox to express his doubts: “God is Auschwitz, but also He who brought me out of there, who obliged, even compelled me to give an account of all that there happened, because He wants to know and hear what he had done.” Often tempted by suicide, Kertész somehow persevered and it was not until 2003 in his novel Felszámolás (Liquidation, 2003) that he produced a hero who actually kills himself. The ending to that book was probably influenced by his recurring depression after he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. In 2014, having lived in Berlin for a number of years, Kertész moved back to Budapest, ostensibly for medical treatment.

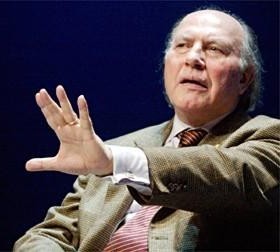

Holocaust survivor who won the Nobel

prize for literature

Imre Kertész survived Auschwitz and

Buchenwald and wrote about his experiences in several books. Photograph:

Guenter Vahlkampf/AFP

‘To write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric,” wrote the German critic Theodor Adorno soon after the second world war. He later modified his statement by saying: “The main question is: can we go on living after Auschwitz?” This was the problem with which the Nobel prize-winning Hungarian Jewish writer Imre Kertész, a survivor of the Holocaust, grappled throughout his life and literary work, until his death at the age of 86. Kertész’s first and most influential novel, Sorstalanság (Fatelessness, 1975), is the story of a 14-year-old boy, Gyuri Köves, who survives deportation to Auschwitz and captivity in Buchenwald, and, on his return to Hungary, finds it impossible to relate his experiences to his surviving family. The book was at first hardly noticed by Hungarian critics and only became a success many years later once it had been translated into German and then, in 2005, made into a film by the Hungarian cinematographer Lajos Koltai. While lacking the biting irony of Tadeusz Borowski’s Auschwitz stories, Sorstalanság differs from most accounts of Nazi concentration camps in its relentless objectivity, and as such is a unique achievement of its kind. It was mainly on the strength of this book, followed by two more novels: A Kudarc (The Failure, 1988) and Kaddis a Meg Nem Született Gyermekért (Kaddish for an Unborn Child, 1990), that Kertész was awarded the Nobel prize for literature in 2002. Kertész was born in Budapest, into a lower-middle-class family. From 1938 laws had been introduced that curtailed the freedom of Hungarian Jews, but the situation changed dramatically in March 1944, when Adolf Hitler invaded the country. Unable to continue his schooling, Kertész, aged 14, was forced to work as a manual labourer. A few months later, he was held in a round up of Budapest Jews and deported to Auschwitz and then Buchenwald, where he survived the war. He returned to Hungary to complete his studies and gain his high school certificate in 1948, and for several years worked as a journalist for the journal Világosság (Clarity). After a spell as a factory worker, he found a position in the press department of the ministry of heavy industry, and from 1953 onwards he was a freelance journalist and translator of literature, in particular of the works of German language writers and philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Hugo von Hoffmanstahl, Elias Canetti, Arthur Schnitzler, Sigmund Freud and Ludwig Wittgenstein. Kertész struggled to get his first novel published in the restrictive atmosphere of Hungary’s communist regime, partly due to his focus on the problem of Jewish identity and its consequences. In Kaddis, the narrator is asked by his wife whether they could have a child. The answer is “no”, because as a survivor of the Holocaust Kertész’s hero finds the human condition almost unbearable. His problem is not finding a place in Hungarian society but “assimilation to life itself”. His decision not to procreate alienates his wife and the marriage breaks up. Advertisement Kertész’s books also sometimes betrayed his ambivalent relationship with religion, which at times led him to doubt the existence of God. In his work Gályanapló (Galley Boat-Log, 1992) he chose a paradox to express his doubts: “God is Auschwitz, but also He who brought me out of there, who obliged, even compelled me to give an account of all that there happened, because He wants to know and hear what he had done.” Often tempted by suicide, Kertész somehow persevered and it was not until 2003 in his novel Felszámolás (Liquidation, 2003) that he produced a hero who actually kills himself. The ending to that book was probably influenced by his recurring depression after he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. In 2014, having lived in Berlin for a number of years, Kertész moved back to Budapest, ostensibly for medical treatment. His last book, A Végső Kocsma (The Ultimate Inn, 2014) was not a conventional novel, but an amalgam of sketches for a would-be novel allied to notes from his diaries of 2001 onwards, mainly on the subject of the decline of the west and his ambivalent feelings about contemporary Hungary, where deeply rooted antisemitic views are still rife and often displayed by unscrupulous politicians. Kertész won numerous literary honours from 1983 onwards, including the Attila József (1989) Márai (1996) and Kossuth (1997) prizes in Hungary, where he was also appointed to the Order of St Stephen, the country’s highest distinction. He received many foreign awards and decorations, too, including the Brandenburg literature prize (1995), the Friedrich Gundolf prize (1997) and the Goethe medal (2004). Kertész is survived by his second wife, Magda Ambrus, whom he married in 1996. His first wife, Albina Vas, died in 1995. • Imre Kertész, writer, born 9 November 1929; died 31 March 2016 http://www.tanvien.net/cn/Trang_Kertesz.html Holocaust survivor who won the Nobel

prize for literature

Imre Kertész survived Auschwitz and

Buchenwald and wrote about his experiences in several books. Photograph:

Guenter Vahlkampf/AFP

‘To write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric,” wrote the German critic Theodor Adorno soon after the second world war. He later modified his statement by saying: “The main question is: can we go on living after Auschwitz?” This was the problem with which the Nobel prize-winning Hungarian Jewish writer Imre Kertész, a survivor of the Holocaust, grappled throughout his life and literary work, until his death at the age of 86. Kertész’s first and most influential novel, Sorstalanság (Fatelessness, 1975), is the story of a 14-year-old boy, Gyuri Köves, who survives deportation to Auschwitz and captivity in Buchenwald, and, on his return to Hungary, finds it impossible to relate his experiences to his surviving family. The book was at first hardly noticed by Hungarian critics and only became a success many years later once it had been translated into German and then, in 2005, made into a film by the Hungarian cinematographer Lajos Koltai. While lacking the biting irony of Tadeusz Borowski’s Auschwitz stories, Sorstalanság differs from most accounts of Nazi concentration camps in its relentless objectivity, and as such is a unique achievement of its kind. It was mainly on the strength of this book, followed by two more novels: A Kudarc (The Failure, 1988) and Kaddis a Meg Nem Született Gyermekért (Kaddish for an Unborn Child, 1990), that Kertész was awarded the Nobel prize for literature in 2002. Kertész was born in Budapest, into a lower-middle-class family. From 1938 laws had been introduced that curtailed the freedom of Hungarian Jews, but the situation changed dramatically in March 1944, when Adolf Hitler invaded the country. Unable to continue his schooling, Kertész, aged 14, was forced to work as a manual labourer. A few months later, he was held in a round up of Budapest Jews and deported to Auschwitz and then Buchenwald, where he survived the war. He returned to Hungary to complete his studies and gain his high school certificate in 1948, and for several years worked as a journalist for the journal Világosság (Clarity). After a spell as a factory worker, he found a position in the press department of the ministry of heavy industry, and from 1953 onwards he was a freelance journalist and translator of literature, in particular of the works of German language writers and philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Hugo von Hoffmanstahl, Elias Canetti, Arthur Schnitzler, Sigmund Freud and Ludwig Wittgenstein. Kertész struggled to get his first novel published in the restrictive atmosphere of Hungary’s communist regime, partly due to his focus on the problem of Jewish identity and its consequences. In Kaddis, the narrator is asked by his wife whether they could have a child. The answer is “no”, because as a survivor of the Holocaust Kertész’s hero finds the human condition almost unbearable. His problem is not finding a place in Hungarian society but “assimilation to life itself”. His decision not to procreate alienates his wife and the marriage breaks up. Advertisement Kertész’s books also sometimes betrayed his ambivalent relationship with religion, which at times led him to doubt the existence of God. In his work Gályanapló (Galley Boat-Log, 1992) he chose a paradox to express his doubts: “God is Auschwitz, but also He who brought me out of there, who obliged, even compelled me to give an account of all that there happened, because He wants to know and hear what he had done.” Often tempted by suicide, Kertész somehow persevered and it was not until 2003 in his novel Felszámolás (Liquidation, 2003) that he produced a hero who actually kills himself. The ending to that book was probably influenced by his recurring depression after he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. In 2014, having lived in Berlin for a number of years, Kertész moved back to Budapest, ostensibly for medical treatment. His last book, A Végső Kocsma (The Ultimate Inn, 2014) was not a conventional novel, but an amalgam of sketches for a would-be novel allied to notes from his diaries of 2001 onwards, mainly on the subject of the decline of the west and his ambivalent feelings about contemporary Hungary, where deeply rooted antisemitic views are still rife and often displayed by unscrupulous politicians. Kertész won numerous literary honours from 1983 onwards, including the Attila József (1989) Márai (1996) and Kossuth (1997) prizes in Hungary, where he was also appointed to the Order of St Stephen, the country’s highest distinction. He received many foreign awards and decorations, too, including the Brandenburg literature prize (1995), the Friedrich Gundolf prize (1997) and the Goethe medal (2004). Kertész is survived by his second wife, Magda Ambrus, whom he married in 1996. His first wife, Albina Vas, died in 1995. • Imre Kertész, writer, born 9 November 1929; died 31 March 2016 http://www.tanvien.net/cn/Trang_Kertesz.html

Imre Kertesz : Cứu rỗi nhờ sách vở. Phỏng vấn giải văn chương Nobel năm 2002 ở Stockholm, văn sĩ người Hung Imre Kertesz. Nhân dịp này Le Point được độc quyền gặp con người có một định mệnh lạ thường, trốn thoát khỏi trại tập trung và chủ nghĩa toàn trị, người không có thói quen thận trọng trong lời nói. Lucien Lambert " 2002 Nobel Laureate in Literature for writing that upholds the fragile experience of the individual against the barbaric arbitrariness of history KERTESZ : Dù báo chí Đức đã nhắc tới nhưng chưa bao giờ tôi nghĩ tôi sẽ được giải. Tôi thấy thật không thể nào có thật được. Và chắc chắn là tôi chưa bao giờ chuẩn bị cho sự kiện này. Có những người ngồi chờ các giải thưởng dài cổ, nếu họ không nhận, chắc chắn họ thất vọng và cay đắng. Tôi không phải như vậy. Vậy tôi chẳng chờ gì ráo... LE POINT : Đời sống của ông sẽ thay đổi? KERTESZ : Đời sống tôi không thay đổi và nó không được thay đổi. Hiện nay tôi đang cật lực làm việc cho quyển tiểu thuyết sắp tới, quyển này tôi đã thai nghén từ lâu. Tôi cảm thấy bây giờ tôi mới nắm được chủ đề. Tôi có cảm giác tôi như người đàn bà mang thai, tự cho phép mình phung phí sức trong ba tháng đầu nhưng sau đó thì phải rất cẩn thận. Tôi vẫn còn hút thuốc, ưống rượu nhưng sau đó thì phải coi chừng. Do vậy tôi tránh các cuộc mời mọc. LE POINT : Ông sắp giàu... KERTESZ : Số tiền này thật đáng kể cho một cây viết lúc nào cũng thiếu tiền. Nói cho thật, tôi rất bằng lòng. Lo âu về tiền bạc sẽ tiêu tan và rồi thì tôi cũng biết được thế nào là sống trong bảo đảm. LE POINT : Từ nhiều năm nay người ta nói rằng giải Nobel văn chương là một chọn lựa chính trị phối hợp để tìm một thế thăng bằng giữa nền văn chương các xứ sở khác nhau... KERTESZ : Tôi từ chối không nói đến chuyện này. Tôi không sao tưởng tượng được những vị ngồi họp chung quanh cái bàn có thể nói: “Bây giờ phải cho nước Hung một giải hay phải tìm một thằng Do Thái người Hung để phát giải năm 2002. » Thành thật mà nói tôi không tin điều này. LE POINT : Ở Budapest, người ta nói rằng ông được giải Nobel nhờ vợ, vợ ông quen biết những người thế lực. Có đúng không ? KERTESZ : Dân ở Budapest biết thật nhiều tin tức! Tôi không biết vợ tôi làm như thế nào, tôi sẽ về hỏi bà. Người ta cũng đã kể cho tôi nghe đủ chuyện trời ơi. Họ kể cho tôi nghe chuyện Hiệp Hội nhà văn Hung... Có thể câu chuyện thế lực là do không hiểu biết. Bà vợ thứ nhì của tôi nửa Hung, nửa Mỹ. Bà sống ba mươi bốn năm ở Chicago. Tôi biết một sự kiện thế lực văn hóa duy nhất: tổ chức buổi hòa nhạc của Dàn Nhạc Đại Hòa Tấu Chicago dưới quyền điều khiển của nhạc trưởng Georg Solti. LE POINT : Ở Hung, người ta nói về ông như một “văn sĩ viết bằng tiếng Hung” hay “văn sĩ Hung». Ông phản ứng như thế nào? KERTESZ : Tôi viết và tôi nghĩ bằng tiếng Hung, ngoài ra tôi không để ý đến gì hết. Tôi nhận được rất nhiều tình cảm từ nước Hung, đại đa số dân chúng xem sự kiện tôi được giải như một thành công to lớn của quốc gia. Từ lâu nước Hung đi tìm cho mình một sự biết đến có tầm cỡ như vậy. Như vậy, đối với người dân Hung, đây là niềm hãnh diện của họ và họ có thể ngẩng đầu lên mà đi. Theo các bạn tôi, đó là điều công bằng thôi. Các ngần ngừ chung quanh nguồn gốc Do Thái của tôi, “chiều kích” kiều bào của tôi, đặc biệt là Đức kiều và những chuyện trời ơi của báo chí cực hữu làm cho tôi bực mình. Thư Ký của Viện Hàn Lâm Thụy Điển kể cho tôi nghe ông còn nhận các e-mail từ Hung nói rằng họ rất tiếc Viện Hàn Lâm Thụy Điển là nạn nhân của cuộc mưu phản quốc tế nhằm mục đích hủy hoại văn hóa Hung. LE POINT : Ông sống giữa Berlin và Budapest. Ông có cảm thấy thoải mái khi ở Đức, một xứ sở mà ông đã từng bị sỉ nhục thậm tệ không? Làm sao ông có thể nói đến chuyện gốc rễ? KERTESZ : Chính ở Berlin các tác phẩm của tôi mới có ảnh hưởng nhất, được đọc nhiều nhất. Tôi đã có lần viết «Holocauste không có ngôn ngữ». Rất nhiều dân tộc sống kinh nghiệm Holocauste và chịu đựng những thảm kịch của Holocauste. Nhưng kinh nghiệm này không có cùng một ngôn ngữ chung. Đây là bi kịch của châu Âu. Những câu chuyện viết bằng tiếng Pháp, tiếng Ý, tiếng Đức... Ngắn gọn, trong ngôn ngữ của nạn nhân. Chẳng hạn, nếu tôi viết sách bằng tiếng Hung và xứ tôi không phù hay chưa sẵn sàng chấp nhận những câu chuyện lấy hứng từ kinh nghiệm, thì lúc đó, tự động tôi thấy tôi ở ngoài nền văn hóa nước tôi. Ngược lại, một văn hóa khác, một ngôn ngữ khác lại dung nhận tôi. Dung nhận vì nền văn hóa đó đã được chuẩn bị. Ở đây, tại Đức, người ta mong chờ các tiểu thuyết mới của tôi. «Kaddish pour l'enfant qui ne naitra pas», xuất bản năm 1992, được báo chí phê bình tốt và «Être sans destin» cũng được như vậy. Khi tôi đọc các thư từ và các bài phê bình viết về các sách của tôi, tôi hiểu nước Đức cần những tiểu thuyết như vậy, cần loại mô tả Holocauste. Nước Đức đối diện với quá khứ... với Lịch Sử của họ và với Auschwitz. Ngày hôm nay, ở Âu châu người ta biết gần như mọi người đều có tham dự vào. Trong lúc đó, thế hệ thứ hai, thế hệ thứ ba lớn lên không có mặc cảm tội lỗi. Các thế hệ này muốn biết làm sao những điều khủng khiếp như thế lại có thể xảy ra. Trong các quyển sách của tôi, họ tìm ra một cái gì có thể giúp họ hiểu rõ hơn những chuyện như vậy. LE POINT : Các chế độ cộng sản ở Đông Âu nuôi dưỡng tư tưởng chống phát-xít như một trong những nền tảng của cuộc chiến chống tư bản chủ nghĩa của họ. Trong hệ thống này, làm sao ông có thể tìm được sự hỗ trợ và thông hiểu như ông đã viết trong “Le refus”? I.KERTESZ : Quyển tiểu thuyết này không thể xếp vào loại chống phát-xít như những người cầm quyền của Đảng mong muốn. Trong quyển sách này, tôi kể tầm chịu đựng đau khổ dưới chế độ phát-xít của chúng tôi và sau đó, sự chiến thắng của Hồng Quân Xô viết “giải phóng” chúng tôi. Đúng ra, tôi viết các tiểu thuyết này vào năm 1960, khi tôi bắt đầu ngấy chế độ Kadar. Trước đó, tôi chứng kiến và sống rất nhiều sự kiện. Ngôn ngữ và bầu khí của những năm 60 và 70 có mặt trong « Le refus ». Quyển sách này không được đón nhận vì tôi theo con đường riêng của tôi, không giống gì con đường của chủ nghĩa xã hội hiện thực. Mặt khác, nó vận chuyển ngôn ngữ của hiện tại. Ngôn ngữ này chứa kíp nổ chống lại chế độ độc tài tại Hung. Chính vì lẽ đó mà họ ghét chúng và họ tìm đủ lý do để từ chối nó.... LE POINT : Ông chưa bao giờ thử làm một hành vi nhỏ nào đó để ve vãn quyền lực? KERTESZ : Tôi sinh năm 1929, tôi sống dưới chế độ sta-lin, tôi thấy cuộc cách mạng 1956. Tôi biết là tôi không được đồng minh với chế độ này. Nếu tôi đăng những truyện ngắn để được trọng dụng, đời viết văn của tôi coi như chấm dứt. Mục đích của tôi là giữ ẩn danh và tôi hoàn toàn thành công. (Ông cười.) LE POINT : Ông có thì giờ để đọc? KERTESZ : Khổ thay tôi có rất ít thì giờ để đọc. Khi mất ngủ tôi lật lật “Nhật Ký Kafka” hay một quyển sách tình cảm “Lịch sử một người Đức,” của Sébastien Haffner. Ông chết năm 1999, để lại bản thảo kể tuổi thanh xuân đi qua dưới bóng chiến tranh và chế độ Nazi. LE POINT : Trong tuổi thanh xuân, ông đọc những gì? KERTESZ : Năm 1949, sau khi hoàn hồn, tôi bắt đầu đọc ngấu nghiến. Tôi không có thư viện gia đình. Gia đình tôi cũng bị chiến tranh làm dìm ngập. Không có hậu cảnh này, tôi có khuynh hướng tin rằng chẳng có loại văn hóa nào trên cõi đất này ngoài loại văn hóa – hèn nhát và nhàm chán – mà chủ nghĩa “xã hội hiện thực” nuôi dưỡng. Thế nên khi tình cờ gặp những quyển sách như “Cái chết ở Venise” “La mort à Venise», của Thomas Mann, tôi thật sự bị ảnh hưởng một cách không thể tin được... Hoặc khi khám phá quyển “Giáo Dục Tình Cảm” « L'éducation sentimentale » của Flaubert, thì tôi hiểu từ đâu tiểu thuyết hiện đại đã bắt đầu. Tôi bị cú sốc văn chương thứ nhì khi Kẻ Xa Lạ của Albert Camus được dịch qua tiếng Hung, vào năm 1957. Đây đúng là một cú mặc khải ảnh hưởng tới sự chọn lựa của tôi. Sau đó tôi khám phá các tác giả như Dostoevski, Kafka. Dù vậy tôi bị hối hận dày vò bởi vì tôi nghĩ tôi phải viết hơn là đọc, nhưng, nhờ Chúa, tôi tiếp tục đọc ngấu nghiến. Đầu những năm 60, tôi thích đọc Nietzsche, Kierkegaard và « Critique de la raison pure » của Kant, quyển này đã làm cho tôi kiểm chứng một cách chính xác những gì tôi cho là hiện hữu, có nghĩa là thế giới không phải là một thực tế khách quan mà hiện hữu thì độc lập với chúng ta, mà thế giới lại là chính tôi. Như thế, chính đó là cái quyết định cái khác biệt giữa tôi và những người tin rằng con người có thể hiện hữu mà không cần kinh nghiệm cuộc sống. LE POINT : Ông mắc nợ Kant cho cuộc tỉnh thức trí tuệ này? KERTESZ : Không! Không chút nào! Ông chỉ chứng nhận là tôi có lý. (Ông cười.) Tôi đọc một mạch quyển này vào một buổi chiều như đọc tiểu thuyết trinh thám. Tôi còn nhớ, vào mùa hè, chúng tôi thuê một túp lều bằng gỗ ở bờ hồ Balaton. Trời mưa không ngừng và tôi ngồi trên bao-lơn xiêu vẹo ngó xuống quốc lộ chính. tôi mở quyển sách và lập tức tôi cảm nhận tôi không còn nghi ngờ gì nữa về tầm nhìn thế giới của tôi. Tôi đối diện với chế độ độc tài mà mỗi ngày loa phóng thanh phóng những chuyện ngu ngốc một cách chính thức, chúng cứ liên tục bác bỏ các luận tưởng của tôi. Tuy nhiên, phải sống dưới chế độ độc tài và không được bằng lòng cho rằng đó là chế độ xấu cần phải cải tổ nhưng phải cho đó là kẻ thù tận căn. Trong chế độ toàn trị, cái căn bản của cuộc sống là phải hiểu mình sẽ bị giết bất cứ lúc nào. Như thế, cảm nhận được an toàn trong một xã hội như vậy là chuyện ảo tưởng. Tin tưởng vào xã hội này là ảo tưởng. LE POINT : Như thế có cuồng hoảng không? KERTESZ : Tôi tin là tôi hoàn toàn không cuồng hoảng. Tất cả các nghệ sĩ vào thời buổi đó đều sống trong cuồng hoảng. Văn sĩ cũng là một con người, thèm thành công, thèm được biết đến. Tôi viết một quyển sách, quý vị thích đi! Cùng một lúc tôi ý thức nếu quyển tiểu thuyết được xem như một biểu tượng, đặt trên bệ thờ, và người ta chính thức yêu thích thì đó là một quyển tiểu thuyết dở. Đó là nghịch lý làm mình bị nghiền nát. Đến một lúc, mình trở nên rất tự hào vì tiểu thuyết của mình không được thành công một cách chính thức, rơi vào thinh lặng, hoàn toàn chẳng ai biết đến. Hai thái độ được kiểm chứng và không lay chuyển. Đương nhiên khi chế độ toàn trị không còn thì các cảm nhận này cũng không còn. LE POINT : Trước chiến tranh, ông sống tuổi thanh xuân như thế nào? KERTESZ : Tôi không cảm thấy thoải mái. Tôi cảm thấy khó chịu trong môi trường tiểu trưởng giả. Đương nhiên là phải giấu chuyện này ở tuổi thanh xuân. Tôi trở thành một người nói dối chuyên nghiệp. Người ta nói rằng tôi là đứa bé chân thành nhưng thật sự tôi luôn luôn nói dối. Tôi đã học cái đạo đức giả khủng khiếp này: chân thành có nghĩa là gì? Nói cho đúng, chính cái không-chân thành là cái mọi người mong chờ. Từ năm 1940, tôi vào học trường công lập nơi có những lớp dành riêng cho người Do Thái. Theo luật bài Do Thái đầu tiên năm 1939 gọi là luật « Numerus clausus », thì chỉ những trẻ em Do Thái học rất giỏi mới được nhận vào trường công. Phản ứng của bà con thân thuộc chung quanh tôi để chống lại hệ thống tuyển chọn này không được mạnh. Lúc đó tôi cảm thấy tôi nằm gọn lỏn trong lớp bọc dối trá khổng lồ này. LE POINT : Ông không bằng lòng điều gì ở những người chung quanh ông? Họ không chống lại hay họ chấp nhận loại hòa nhập này? KERTESZ : Đó là cái cố gắng để hòa nhập vào. Cái khủng khiếp là cái hòa vào khuôn khổ, nó trở nên một cách sống ở Hung vào thời buổi đó. Tôi, tôi sống như thế từ tuổi thơ ấu. Tôi không phê phán chế độ đó, tôi phê phán tôi. Tôi nhục nhã. Kết quả: tôi có điểm xấu, tôi thi rớt. LE POINT : Ông thích làm gì vào thời buổi đó? KERTESZ : Đọc. LE POINT : Các phê bình những năm 60-70 chê trách thái độ bi quan và cay đắng của ông. Ông có còn cay đắng và không hy vọng cho tương lai nhân loại? KERTESZ : Tôi chưa bao giờ nói tương lai nhân loại không có lối thoát. Sai. Tôi chưa bao giờ bôi đen thực tế. Ông có biết sự khác biệt giữa một người bi quan và một người lạc quan không? Người bi quan là người có những thông tin rõ ràng: đó là người lạc quan sáng suốt. Tôi không nghĩ là cần phải chối bỏ mọi sự kiện đề cảm thấy mình tự do. Tôi nghĩ chính cái hiểu biết mới thật sự giải thoát cho con người. LE POINT : Ông phải bỏ ra mười năm để viết quyển tiểu thuyết đầu tiên. Lúc nào ông cũng viết chậm rãi như thế sao? KERTESZ : Đúng, tôi viết rất khó khăn. Thường thường tôi tự tra tấn vặn vẹo cả mấy năm trường để tìm cho được một hình thức tốt nhất. Đối với tôi, trên mặt kỹ nghệ, cán viết không phải là một nghề sinh lợi. Đương nhiên, ý tưởng này sẽ thay đổi khi được giải Nobel. Khi tôi lên xe lửa để đi đến, tôi không nghĩ đến viễn cảnh giải Nobel. Như người ta nói, không phải vì vậy mà mình có hợp đồng. (Ông cười.) Tương lai bất định chính nó cũng đã mang hiểm họa. Nghề viết văn mang hiểm họa này. Tôi sống với hiểm họa này như một cuộc phiêu lưu khủng khiếp. Chính vì vậy mà tôi yêu nó. Lan Nguyễn chuyển ngữ |