|

|

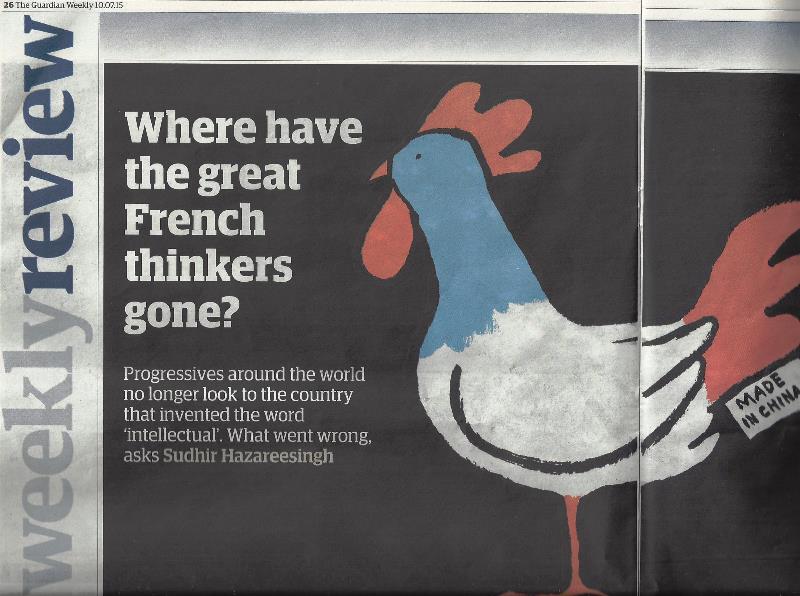

Album | Thơ | Tưởng Niệm | Nội cỏ của thiên đường | Passage Eden | Sáng tác | Sách mới xuất bản | Chuyện văn Dịch thuật | Dịch ngắn | Đọc sách | Độc giả sáng tác | Giới thiệu | Góc Sài gòn | Góc Hà nội | Góc Thảo Trường Lý thuyết phê bình | Tác giả Việt | Tác giả ngoại | Tác giả & Tác phẩm | Text Scan | Tin văn vắn | Thời sự | Thư tín | Phỏng vấn | Phỏng vấn dởm | Phỏng vấn ngắn Giai thoại | Potin | Linh tinh | Thống kê | Viết ngắn | Tiểu thuyết | Lướt Tin Văn Cũ | Kỷ niệm | Thời Sự Hình | Gọi Người Đã Chết Ghi chú trong ngày | Thơ Mỗi Ngày | Chân Dung | Jennifer Video Nhật Ký Tin Văn / Viết Nhật Ký Tin Văn [TV last page] Sách Báo  Những “Maitres” của Tẩy ngày nào, nay đâu rồi?

French philosophy has had precious little to offer in recent decades.

Triết Tẩy mấy thập niên gần đây chẳng có gì dâng hiến cho nhân loại, dù tí ti, thực quí hiếm. Liệu Tẩy còn.. suy tư?

Writing after the end of the Second World War, the French

historian Andre Siegfried claimed that French thought had been the driving

force behind all the major advances of human civilization, before concluding

that "wherever she goes, France introduces clarity, intellectual ease, curiosity,

and ... a subtle and necessary form of wisdom". This ideal of a global French

rayonnement (a combination of expansive impact and benevolent radiance) is

now a distant and nostalgic memory. French thought is in the doldrums. French

philosophy, which taught the world to reason with sweeping and bold systems

such as rationalism, republicanism, feminism, positivism, existentialism

and structuralism, has had conspicuously little to offer in recent decades.

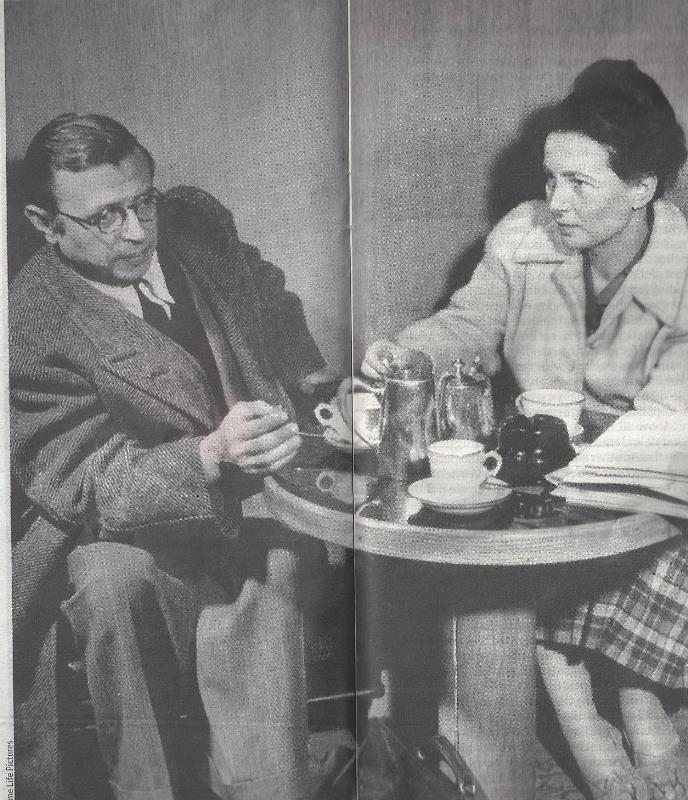

Saint -Germain-des-Prés, once the engine room of the Parisian Left Bank's

intellectual creativity, has become a haven of high - fashion boutiques,

with fading memories of its past artistic and literary glory. As a disillusioned

writer from the neighborhood noted grimly: "The time will soon come when

we will be reduced to selling little statues of Sartre made in China!' French

literature, with its once glittering cast of authors, from Balzac and George

Sand to Jules Verne, Albert Camus and Marguerite Yourcenar, has likewise

lost much of its global appeal - a loss barely concealed by recent awards

of the Nobel Prize for literature to JMG Le Clezio and Patrick Modiano. In

2012, the Magazine Littéraire sounded the alarm with an apocalyptic headline:

"La France pense-t-elle encore?" ("Does France still think?")Nowhere is this retrenchment more poignantly apparent than in France's diminishing cultural imprint on the wider world. An enduring source of the French pride is that their ideas and historical experiences have decisively shaped the values of other nations; Versailles in the age of the Sun King was the unrivalled aesthetic and political exemplar for European courts. Caraccioli, the 18th-century author of L'Europe Francaise, expressed a common view when he enthused about the "sparkling

nay trở thành nơi bán hàng hiệu, và chẳng chóng thì chầy, sẽ bày bán, tượng Sartre, như món quà lưu niệm, “made in China”! The forty-five typewritten pages of Franz

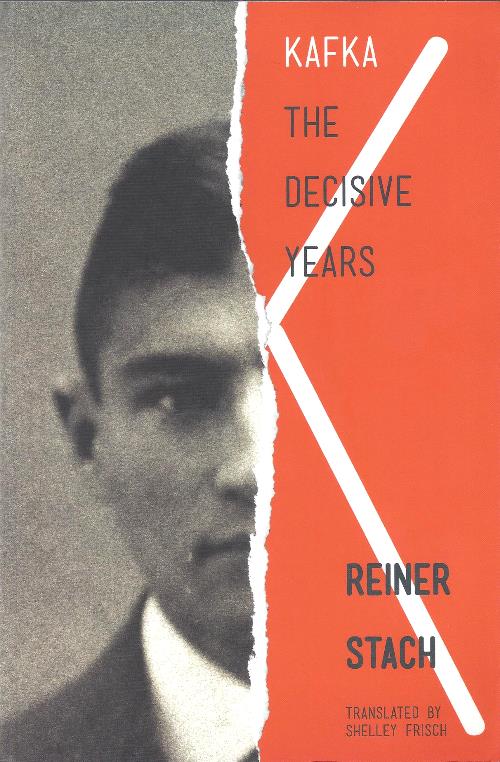

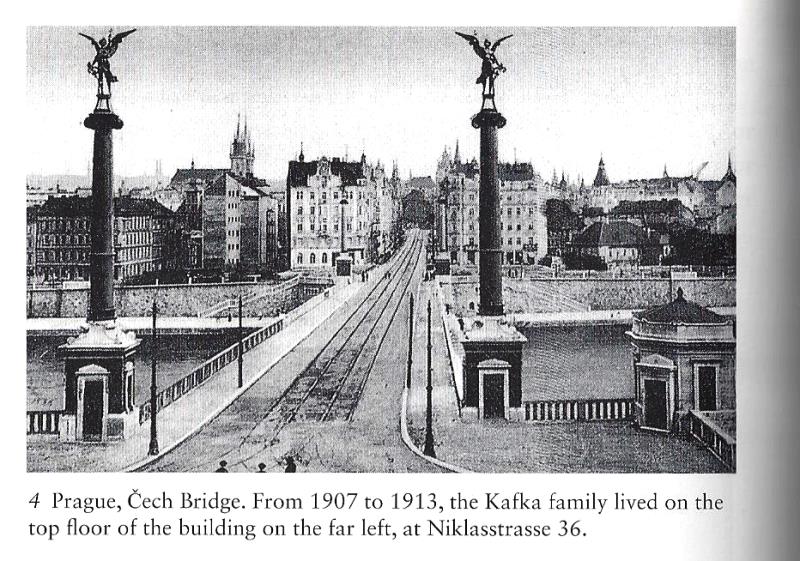

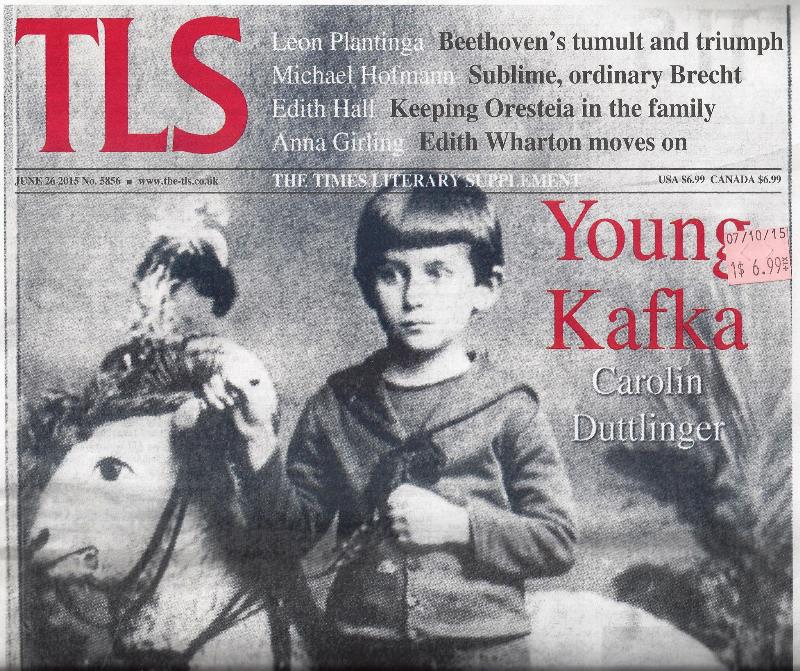

Kafka's "Letter to his Father" are, as Carolin Duttlinger says, "the closest

we have to Kafka's memoirs". Now, with the publication of Kafka: Die friihen

Jahre (The early years), Reiner Stach's three-volume, 2,000- page work on

the not quite forty-one years of Kafka's life is complete. "Counteracting

perceptions of Kafka as somewhat removed from the major events of his time",

Stach shows "how Kafka's life story is closely entwined with ... the fabric

of modernity"; the trilogy is "a true landmark of biographical scholarship".

Kafka, Những năm quyết

định.

Đám điểm sách, nhà văn, phê bình gia, toàn thứ dữ, khen cuốn này thấu trời, đành phải bệ về! Farewell,

you little street, Two weeks

later, he [Brod] received a piece of poetry from Jungborn. It was just

as

"pure," but in a very different way. It was a popular song that Kafka

had sung along to a few times without being able to get the melody

quite right.

It was called "In the Distance" and was about as old as Kafka

himself. This song, by Albert Graf von Schlippenbach, was folksy, which

is a

euphemism for trivial. Yet it cut Kafka to the quick. Just a few months

later,

he confessed to a woman that he was "in love" with this song. He sent

her a copy of the text but asked to have it back because he could not

do

without it; "pure emotion" had been rendered in perfect form in this

text. Without further

elaboration, he added, "And I can swear that the poem's sorrow is

genuine." Reiner Stach:

Kafka: The Decisive Years Translated [from

German] by Shelley Frisch  Chapter 23 Literature,

Nothing but Literature I have known

for many years -ILSE

AICHINGER, EISKRISTALLE Không viết là cái phần căng nhất, dài nhất, trong cái nghề này.

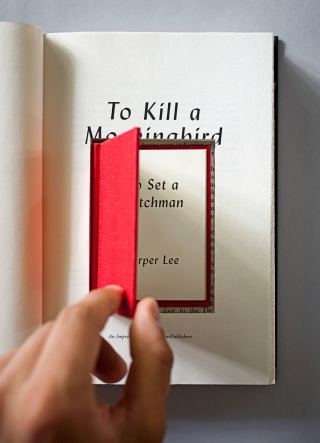

Sweet Home Alabama

The New Yorker đọc cuốn tiểu thuyết mới kiếm thấy của tác giả “Giết con chim nhại”. Then Scout asks, “Did you hate us?,” and Calpurnia shakes her head no. This is credible. But the scene, and the book, would have been stronger if she hadn’t. ♦ Rồi Scout hỏi " Chị có ghét chúng tôi không ?" và Calpurnia lắc đầu "không" . Điều này có thể tin được . Nhưng cái cảnh này, và cả cuốn sách, sẽ "bảnh" hơn nhiều nếu chị ta đừng lắc đầu . Làm nhớ Faulkner: Hãy Nói Về Miền Nam "Tại sao anh thù ghét Miền Nam?", Shreve McCannon hỏi, sau khi nghe xong câu chuyện – "Tôi không thù Miền Nam", Quentin trả lời liền lập tức. "Tôi không thù Miền Nam," anh lập lại, như thể nói với tác giả, và với chính mình. Tôi không thù …. Tôi không. Tôi không thù! Tôi không thù! William Faulkner. Absalom, Absalom! (1936) Có thể, Adam Gopnik, cũng nghĩ tới Faulkner, khi kết thúc bài điểm sách của ông. Note: Bài trên The Economist, của Prospero, đọc thú hơn. Tay này, quả là 1 cao thủ trong giới điểm sách. Harper Lee’s new novel Scout grows up http://www.economist.com/blogs/prospero/2015/07/harper-lee-s-new-novel Jul 14th 2015, 11:24 by The Economist FOR more than half a century “To Kill a Mockingbird” has been revered as a literary classic, the story of Scout and Jem Finch, a young sister and brother (and their naughty friend, Dill Harris, based on Truman Capote) who are all trying to make sense of the bewildering, bigoted American South in the 1930s. The novel sold 40m copies, won a Pulitzer prize and was made into a much-loved film, starring Gregory Peck as the siblings’ father, Atticus Finch, a heroic white lawyer who defends a black man accused of raping a white woman. Its fame was enhanced by what happened to its author, Harper Lee, who was only 34 when the book came out. Now 89 and living in a home, she has turned down every interview request for more than 50 years. For decades it was thought that Ms Lee had written nothing else. But in 2014 her lawyer, Tonja Carter, discovered an unpublished manuscript titled “Go Set a Watchman”. The book was released on July 14th with simultaneous editions translated into seven languages. Six months of teasers from her publishers ensured it was the publishing moment of the year, with early orders approaching Harry Potter levels. The novel is being touted as a sequel to “Mockingbird”, but it would be truer to call it an early prototype. Instead of a child, Scout is a 26-year-old woman who works in New York and has gone home on holiday, much as Ms Lee herself might have done at the time. Tay Hohoff, her legendary editor, read the draft in 1957 and wisely advised the fledgling author to rewrite the book, fleshing out the scenes of Scout’s childhood. Early reactions to the new release have focused on the shocking disclosure that Atticus Finch, far from being a hero, is an uneasy segregationist who once attended a Ku Klux Klan meeting. As one fan tweeted, “It’s like hearing that Santa Claus beat his deer.” The book’s evolution from “Watchman” into “Mockingbird” in less than three years is remarkable. To put it into context, a lot of novels are dreadful, and most are ordinary. Even the 150 or so submitted for the Man Booker prize every year—supposedly the cream of literary publishing—are a mixed bunch. Only a handful, if that, could be considered great. “Go Set a Watchman” is one of the ordinary ones. It has flashes of delight—the 14-page account of a ladies’ coffee morning is particularly hilarious. But many of the characters are one-dimensional and they spout long speeches, chiefly about race, that feel both unfinished and undigested. That Atticus Finch should reveal himself to his adult daughter as a racist bigot, rather than the moral giant of “Mockingbird”, can only have been written by someone who had not had a child or seen at first hand the inexorable nosiness of the young, whether about their parents’ motives or their sex lives. The most surprising thing about “Go Set A Watchman”, then, is how a young writer, so rooted in the customs and mores of her time and seemingly with no sense of drama or history, was able to transform a first novel from a pedestrian piece of prose into a soaring work that has enthralled millions through the decades. It makes one want to salute the human imagination—and weep that she never wrote more. Bài sau đây, cũng của Prospero, viết về văn học Israrel, cũng thật OK. Cái "open wound" của nó, liệu có giống của VC không, khi chúng không làm sao "đọc đúng" văn chương Miền Nam trước 1975. Mỗi lần đọc, là chúng bèn thiến những gì cần đọc Israeli literature

http://www.economist.com/blogs/prospero/2015/07/israeli-literature All change

ISRAEL has been immigrant-based from its founding, but the country’s cultural output has not always reflected that diversity. Ashkenazi Jews with roots in central and eastern Europe formed the country’s early elites, and art, literature and film often sought to assimilate newcomers. But a recent spate of literary awards suggest this may be changing. Earlier this year there was a furore when the country’s Sapir prize went to Reuven Namdar, a Jew whose family came to Israel from Iran, but who now lives in New York. The winner of this year’s Israeli Prize in Literature, Erez Biton, is a Jewish poet whose family emigrated from the Arab world and who was born in Algeria. Dalia Betolin-Sherman, an emigre from Ethiopia (pictured above), won the 2014 Ramat Gan prize for her first collection of stories. One of the country’s most popular writers, Sayed Kashua, is a Muslim Israeli Arab who writes in Hebrew. A novelist, television writer and newspaper columnist, he is based in Illinois. While such writers' location, ethnicity and religion differ, they have all primarily written in Hebrew. But the nearly 1m Russian emigres who moved to Israel in the 1990s have their own thriving literary community and publish novels in Russian about life in their adopted home. What defines Israeli literature as “Israeli” is increasingly up for debate. “Israeli literature should reflect reality as it is today," argues Ms Betolin-Sherman, "and not necessarily be the same thing it was 60 years ago.” Her own story collection—“When the World Became White”—focuses on the country’s 135,000-strong Ethiopian Jewish minority and is due to be published in English by Penguin in 2017.

The forty-five typewritten pages of Franz

Kafka's "Letter to his Father" are, as Carolin Duttlinger says, "the closest

we have to Kafka's memoirs". Now, with the publication of Kafka: Die friihen

Jahre (The early years), Reiner Stach's three-volume, 2,000- page work on

the not quite forty-one years of Kafka's life is complete. "Counteracting

perceptions of Kafka as somewhat removed from the major events of his time",

Stach shows "how Kafka's life story is closely entwined with ... the fabric

of modernity"; the trilogy is "a true landmark of biographical scholarship".

Tờ Guardian có bài, triết gia Tẩy, đâu hết rồi, thật là tuyệt. Bèn đi liền.

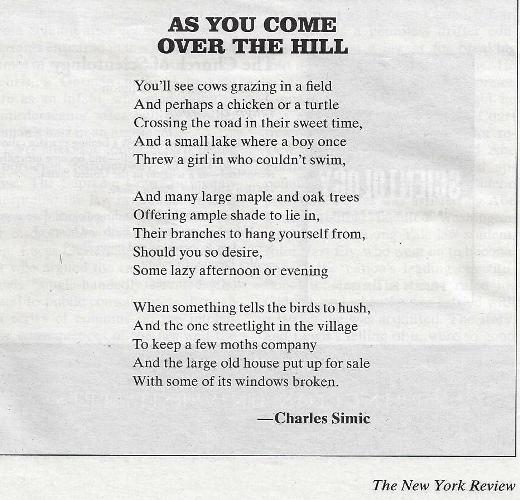

Charles Simic, New York City, May 1996

Hầu như “tất

cả” những bài thơ trong “The Lunatic” đã được Tin Văn dịch, lai rai

trước đó,

chôm từ những tạp chí, và, khi cuốn thơ được xb, làm trọn cả ổ. Cũng không

cho đọc free, là 1 bài thật OK, của Vargas Llosa, trong 1 cuốn sách sẽ

xb trong

những ngày sắp tới. Trên tờ Harper's Lạ, là bài

viết làm Gấu nhớ tới thời gian mới tới Trại Cấm Thái Lan, chưa từng

biết phim

sex là cái gì, bữa đó, nghe 1 em Bắc Kít, hình như là 1 nữ

thương gia

làm ăn thất bát, hoặc, vượt biển theo bồ, 1 anh chàng hình như gốc Tẫu,

quen

thân tay Trưởng Trại Thái Lan, Gấu lúc đó làm tên dậy tiếng Anh cho

những vì học

trò thần thế như thế. Gấu không

làm sao hiểu được phim “séc” là phim gì. Thú nhất là

lần ở tù VC, nghe 1 ông, bạn tù kêu là ông Sơn Mê Ô, cứ tưởng gốc

Tẩy, chỉ đến

khi ông hút điếu thuốc lào thì mới hiểu, đây là ông “Sơn Méo”, vì

ông hút lệch

hẳn miệng qua 1 bên, chỉ một nửa điếu thuốc lào, nửa còn lại là của 1

ông đang

ngồi chờ đến phiên mình! Tuyệt nhất, trong The Lunatic, với riêng Gấu, là bài Lên Đồi Hóng Gió. Thảm nhất, là bài kế tiếp,

dưới đây.

NYRB May 9,

2013

Bạn sẽ thấy bò gặm cỏ trên

đồng

Và có lẽ, một chú gà con, hay một con rùa Băng qua đường trong cái khoảng thời gian Ui chao thật là ngọt ngào của chúng Và một hồ nhỏ, nơi có lần một đấng con trai Ném cô gái của mình xuống đó Cô gái, tất nhiên, đếch biết bơi! Hà, hà! Và rất nhiều cây phong to tổ bố, và sồi Xoè cái váy của chúng ra, Là cái bóng dâm rộng lùng thùng là những tầng lá Để bạn nằm lên đó Còn những cành cây, là để bạn treo tòng teng bạn lên Thì cứ giả như bạn đang thèm Một buổi xế trưa lười biếng hay, Quá tí nữa, 1 buổi chiều. Khi một điều gì đó nói, bầy chim, im đi Và ngọn đèn đường độc nhất ở trong làng, Giữ mấy con bướm đêm làm bạn đường Và ngôi nhà thật rộng, cũ mèm, để biển bán Với mấy cửa sổ bể, gãy, tan hoang. Bài thơ có bề ngoài giống y chang 1 bài ca dao, thí dụ bài “Trèo lên cây bưởi hái hoa”, ở đây, là lên đồi ngắm cảnh. Những “tỉ” những “hứng” có đủ cả… Nói theo Kim Dung, thì chúng là những đòn gió, chỉ để bất thình lình ra đòn sau cùng, đòn chí tử, là khổ thơ chót. Đọc, sao mà thê lương chi đâu: When something tells the birds to hush, And the one streetlight in the village To keep a few moths company And the large old house put up for sale With some of its windows broken. Quái làm

sao, câu thơ đầu,

“khi một điều gì đó nói lũ chim câm đi”, làm Gấu nhớ đến cái mail chót,

của 1 nữ thi sĩ, “mi làm phiền ta quá”… “kiếp trưóc mi đúng là con

đỉa”….

Hà hà! Nhưng cái mail kế chót thì thật là tuyệt vời. Em quả có tí thương [hại] Gấu! Passing

Through An

unidentified, London

Review of Books 9 May 2013 Quá Giang Một tên nào

đó Ui chao đọc

bài thơ này, thì lại nhớ, 1 lần, Gấu nằm mơ, sống lại những ngày Mậu

Thân, cực

kỳ thê thảm, và hình như khóc khủng khiếp lắm. Phải mãi sau

này, khi nghĩ lại cái lần Gấu xin gặp mặt, nhân cả hai cùng ghé Tiểu

Sài Gòn, và

nghe trả lời, mi muốn gặp ta ư, thì đến dự bữa tiệc ra mắt sách của nhà

văn gì gì đó,

nhà xb Cờ Lăng, ta làm MC, ở…. Gấu mới té ngửa, tại làm sao mà lại có

sự

lầm lẫn

lớn lao như thế này. Hoá ra cuộc tình "giả" như

thế - thì có gì thực đâu – mà cực kỳ thê lương, đó là vì nó được cuộc

chiến, trong có hai tên

sĩ quan

Ngụy, một, là thằng em trai, một, là người chồng, làm nền cho nó. Some of

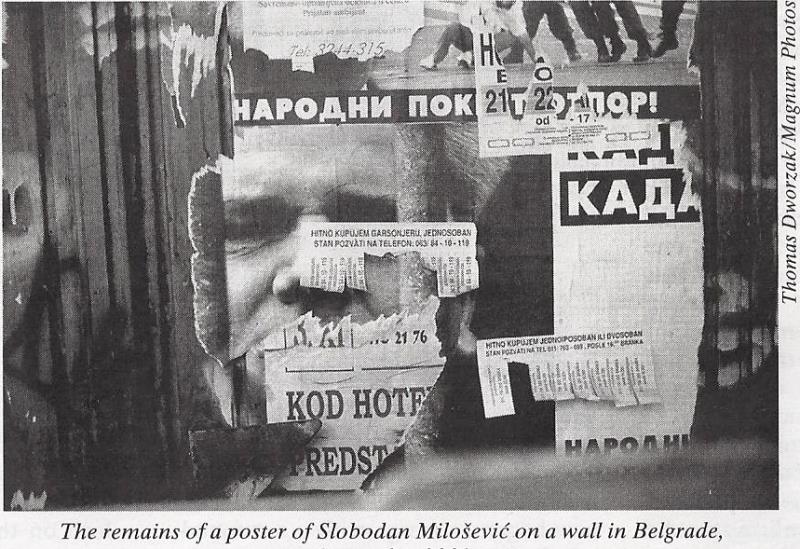

Simic's most powerful, expressive prose can be found in three essays

that deal

with the breakup of Yugoslavia. His opposition to any utopian project,

including nationalism, which would place a collective interest above

the safety

of the individual, is unremitting. As Slobodan Milosevic was taking

power in

Serbia, Simic warned early on that he was "bad news," and for his

pains was denounced by Serbian nationalists as a traitor. His answer:

"The

lyric poet is almost by definition a traitor to his own people." As he

saw

it, "sooner or later our tribe always comes to ask us to agree to

murder," which is one good reason he has resisted tribal identification

with a passion: "I have more in common with some Patagonian or Chinese

lover of Ellington or Emily Dickinson than I have with many of my own

people." Leery of all generalizations, he insists again and again that

"only the individual is real." As the civil war heated up, he found

that his appeals to forgiveness and reasonableness were met with total

incomprehension and finally hatred. Simic, living in America, became

the target

of rumors: My favorite

one was that the CIA had paid me huge amounts of money to write poems

against

Serbia, so that I now live a life of leisure in a mansion in New

Hampshire

attended by numerous black servants. If he is

still able to extract wry humor from the situation, elsewhere he rises

to a

furious eloquence. There is no longer any hint of mystery or the

"unsayable" in these political essays; he knows exactly what he wants

to say: All that became obvious to

me watching the dismemberment of Yugoslavia,

the way opportunists of every stripe over there instantly fell behind

some vile

nationalist program. Yugoslav identity was enthusiastically canceled

overnight

by local nationalists and Western democracies in tandem. Religion and

ethnicity

were to be the main qualifications for citizenship, and that was just

dandy.

Those who still persisted in thinking of themselves as Yugoslavs were

now

regarded as chumps and hopeless utopians, not even interesting enough

to be

pitied. In the West many jumped at the opportunity to join in the fun

and

become ethnic experts. We read countless articles about the rational,

democratic, and civilized Croats and Slovenes, the secular Moslems,

who, thank

God, are not like their fanatic brethren elsewhere, and the primitive,

barbaric, and Byzantine Serbs and Montenegrins .... `With finely controlled

sarcasm, Simic

demonstrates the advantages of an emigre's double vision. It enables

him to see

how his uncle Boris "had a quality of mind that I have often found in

Serbian men. He could be intellectually brilliant one moment and

unbelievably

stupid the next." If Simic is finally harder on the Serbs, despite

acknowledging that there were war criminals in every faction, he

explains:

"Nonetheless, it is with the murderers' in one's own family that one

has

the moral obligation to deal first." a larger

setting for one's personal experience. Without some sort of common

belief,

theology, mythology-or what have you-how is one supposed to figure out

what it

all means? The only option remaining, or so it seems, is for each one

of us to

start from scratch and construct our own cosmology

as we lie in bed at night. At age seventy-seven he is still starting from scratch, and writing in bed, his favorite writing spot, alone with the moth, there being, as he sees it, no other option. + Nhà thơ trữ

tình thì hầu như ngay từ định nghĩa, 1 tên phản bội nhân dân của nó,

chẳng sớm

thì muộn, bộ lạc sẽ tới đề nghị anh ta làm đao phủ thủ. How

important is Milan Kundera today? In the 1980s

everybody was reading The Unbearable Lightness of Being and The Book of

Laughter and Forgetting. But, as he publishes a novel for the first

time in a

dozen years, what is the Czech writer’s reputation today – and is it

irretrievably damaged by his portrayal of women? Danh tiếng Kundera ngày

nay ra sao? (*) Trong những năm 1980 mọi người đều

đọc Đời nhẹ khôn kham (The Unbearable Lightness of Being)

và Cười cợt và quên lãng (The Book of

Laughter

and Forgetting).

Nhưng, khi ông xuất bản cuốn

tiểu thuyết đầu tiên sau hàng chục

năm,

danh tiếng của nhà văn gốc Tiệp này ngày nay ra sao – phải

chăng nó

đã bị hủy hoại không thể cứu vãn do cách miêu tả phụ nữ của

ông? Câu tiếng Việt, nhảm. Ý của nó như vầy, "Nhưng, khi ông xuất bản cuốn tiểu thuyết, lần đầu tiên, sau cả chục năm [bặt tiếng], thế giá của ông bây giờ như thế nào - liệu nó có bị sứt mẻ trầm trọng, hết thuốc chữa, do cách ông miêu tả người phụ nữ?" Cái tít tiếng

Việt cũng nhảm. Tiếng Anh, “sự quan trọng của Kun bây giờ như thế nào”,

là ý muốn

nói, ông này, từ lò CS chui ra, viết 1 cú là nổi như cồn, vì những câu

phán cực

là bảnh tỏng, như "chân lý nước Việt Nam là một", thí dụ, “The struggle

of man against power is the

struggle of

memory against forgetting”, cuộc chiến đấu của con người chống lại

quyền lực là

cuộc chiến đấu của hồi nhớ chống lại sự lãng quên; bây giờ sự quan

trọng của ông như thế nào, là ý đó. Gấu có thể là

người đầu tiên giới thiệu Kun với độc giả hải ngoại, nhưng chắc chắn,

là người đầu

tiên khui ra chi tiết này, trong thế giới toàn trị vách nhà giam dán

đầy thơ, và

mọi người nhẩy múa trước những bài thơ đó, và VC Bắc Kít bảnh hơn cả

"Bố của

VC", tức Liên

Xô, bởi là vì ở Liên Xô, ngai vàng Điện Cẩm Linh được thi sĩ và đao phủ

thủ cùng ngồi, nhưng ngai vàng ở Bắc Bộ Phủ, một mình Văn Cao là đủ! Với tôi, hay

nhất ở Phạm Duy, vẫn là những bản nhạc tình. Ông không thể, và chẳng

bao giờ muốn

đến cõi tiên, không đẩy nhạc của ông tới tột đỉnh như Văn Cao, để rồi

đòi hỏi

"thực hiện" nó, bằng cách giết người. Một cách nào đó, "tinh thần"

Văn Cao là không thể thiếu, bắt buộc phải có, đối với "Mùa Thu", khi

mà nhà thơ ngự trị cùng với đao phủ. Kundera đã nhìn thấy điều đó ở

thiên tài

Mayakovsky, cũng cần thiết cho Cách mạng Nga như trùm cảnh sát, mật vụ

Dzherzhinsky. (Những Di chúc bị Phản bội). Nhạc không lời, ai cũng đều

biết, mấy

tướng lãnh Hitler vừa giết người, vừa ngắm danh họa, vừa nghe nhạc cổ

điển. Cái

đẹp bắt buộc phải "sắt máu", phải "tyranique", (Valéry). Phạm

Duy không nuôi những bi kịch lớn. Ông tự nhận, chỉ là "thằng mất dậy"

(trong bài phỏng vấn kể trên). Với kháng chiến, Phạm Duy cảm nhận ngay

"nỗi

đau, cảnh điêu tàn, phía tối, phía khuất", của nó và đành phải từ chối

vinh quang, niềm hãnh diện "cũng được chính quyền và nhân dân yêu lắm".

Những bài kháng chiến hay nhất của Phạm Duy: khi người thương binh trở

về. Ở

đây, ngoài nỗi đau còn có sự tủi hổ. Bản chất của văn chương "lưu vong,

hải

ngoại", và cũng là bản chất của văn chương hiện đại, khởi từ Kafka, là

niềm

tủi hổ, là sự cảm nhận về thất bại khi muốn đồng nhất với đám đông, với

lịch sử,

với Mùa Thu đầu tiên của định mệnh lưu vong. Phạm Duy muốn

làm một người tự do tuyệt đối nên đã bỏ vào thành. Nhưng Văn Cao, chỉ

vì muốn đồng

nhất với tự do tuyệt đối, nên đã cầm súng giết người. Thiên tài

Mayakovski cần

thiết cho Cách Mạng Nga cũng như trùm công an mật vụ, là vậy. "Mặt trời

chân lý chiếu qua tim". (Tố Hữu). Tính chất trữ tình không thể thiếu,

trong thế giới toàn trị (totalitarian world): Tự thân, thế giới đó

không là ngục

tù, gulag. Nó là ngục tù, khi trên tường nhà giam dán đầy thơ và mọi

người nhẩy

múa trước những bài thơ đó, (Kundera, sđd).

Kundera

« Ce n'était

pas seulement le temps de l'horreur, c'était aussi le temps du lyrisme!

Le

poète régnait avec le bourreau ". Thời Của Văn Cao: Thi sĩ lên ngôi trị vì cùng với đao phủ. Roman

= poésie antilyrique Michael

Hofmann The Festival

of Insignificance by Milan Kundera, translated by Linda Asher Faber, 115

pp, £14.99, June, ISBN 978 0 571 31646 5 Tờ LRB,

Michael Hofmann đọc “Lễ Hội Cà Chớn” của Kun.“Cũng” chê. Hết thời rồi. Thập niên 80 là của Kun. Khi bạn không kịp

đọc cuốn cũ, thì có ngay cuốn mới. Nhưng

bạn

trẻ ơi, young reader, tôi – Michael Hofmann - hết đọc rồi. Ít ra, hết

đọc Kun,

no more Kundera!

[Essay] ARS EROTICA By Mario

Vargas Llosa, from Notes on the Death of Culture: Essays on Spectacle

and

Society, out next month from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Vargas Llosa,

who is

the author of more than a dozen novels, received the Nobel Prize for

Literature

in 2010. Translated

from the Spanish by John King. A few years ago, a small media storm erupted in Spain when the Socialist government in the region of Extremadura introduced, as part of its sex-education curriculum, masturbation workshops for girls and boys over the age of thirteen-a program that it somewhat mischievously called Pleasure Is in Your Own Hands. Faced with protests, the regional government argued that sex education for children was necessary to "prevent undesirable pregnancies" and that masturbation classes would help young people "avoid greater ills." In the ensuing debate, the regional government of Extremadura received support from the regional government of Andalucfa, which announced that it would soon roll out a similar program. An attempt by an organization close to the Popular Party to close down the masturbation workshops by way of a legal challenge-called, equally mischievously, Clean Hands-failed when the public prosecutor's office refused to take up the complaint. How things have changed since my childhood, when the Salesian fathers and La Salle brothers who ran the schools scared us with the idea that "improper touching" caused blindness, tuberculosis, and insanity. Six decades later schools have jerking-off classes. Now that is progress. But is it really? I acknowledge the good intentions behind the program and I concede that campaigns of this sort might well lead to a reduction in unwanted pregnancies. My criticism is of a sensual nature. Instead of liberating children from the superstitions, lies, and prejudices that have traditionally surrounded sex, might these masturbation workshops trivialize the act even more than it has already been trivialized in today's society? Might they continue the process of turning sex into an exercise without mystery, dissociating it from feeling and passion, and thus depriving future generations of a source of pleasure that has long nurtured human imagination and creativity? Masturbation does not have to be taught; it can be discovered in private. It is one of the activities that compose our private lives. It helps boys and girls break out of their family environment, making them individual and revealing to them the secret world of desire. To destroy these private rituals and put an end to discretion and shame-which have accompanied sex since the beginning of civilization-is to deprive sex of the dimension it took on when culture turned it into a work of art. The disappearance of the idea of form in sexual matters-like its disappearance from art and literature-is a kind of regression. It reduces sex to something purely instinctive and animalistic. Masturbation classes in schools might do away with stupid prejudices, but they are also another stab at the heart of eroticism- perhaps a fatal one. And who would benefit from eroticism's final death? Not the libertarians and the libertines, but the puritans and the churches. Of course, these workshops are only a minor manifestation of a sexual liberation that is among modern democratic' society's most important achievements. They are another step in the ongoing effort to do away with the religious and ideological restrictions that have constrained sexual behavior from time immemorial, causing enormous suffering. This movement has had many suite Bài tiểu luận

của Vargas Llosa về nghệ thuật sex, cực thú vị. Nó làm Gấu nhớ tới lần

đầu tiên

biết may tay, nhờ ông cậu, Cậu Hồng, ông con trai độc nhất của Bà Trẻ

của Gấu. Ông

gọi nó là ‘rung’, “nghệ thuật rung”, nói theo Thầy Vargas Llosa!  * aristos is

taken from the ancient Greek. It is singular and means roughly 'the

best for a

given situation'. It is stressed on the first syllable. 35. Emily

Dickinson: If summer were an axiom, what sorcery had snow?

* * Emily

Dickinson. Nữ thi sĩ lớn, cô đơn, Mẽo, người mà cái đòi hỏi sáng ngời

của nghịch biện thì được hôn phối với cái đốn ngộ sâu sa về bản chất

của nỗi

khổ đau của con người. John Fowles

chỉ mê hai nhà thơ, I think of two poets whose poetry I have a special

love

for: Catullus and Emily Dickinson.  I died for

beauty; but was scarce

Adjusted in the tomb, When one who died for truth was lain In an adjoining room. He questioned softly why I failed? "For beauty," I replied. "And I for truth-the two are one; We brethren are," he said. And so, as kinsmen met a night, We talked between the rooms, Until the moss had reached our lips, And covered up our names.  Emily Dickinson: An Introduction Bây giờ

Emily Dickinson được nhìn nhận, không chỉ như 1 nhà thơ lớn của Mẽo,

thế kỷ 19,

nhưng còn là nhà thơ quái dị, gợi tò mò, intriguing, nhất, ở bất cứ

thời nào,

hay nơi nào, cả ở cuộc đời lẫn nghệ thuật của bà. Tiểu sử ngắn gọn về

đời bà thì

cũng có nhiều người biết. Bà sinh ở Amherst, Mass, vào năm 1830, và,

ngoại trừ

vài chuyến đi xa tới Philadelphia, Washington, Boston, bà trải qua trọn

đời mình, quanh quẩn nơi căn nhà của người cha. “Tôi không vượt quá

mảnh đất của

Cha Tôi – cross my Father’s ground - tới bất cứ một Nhà, hay Thành

Phố”, bà viết

về cái sự thụt lùi, ở ẩn, her personal reclusiveness, khiến ngay cả

những người

cùng thời của bà cũng để ý, noticeable. Tại căn phòng ngủ ở một góc

phía

trước căn nhà, ở đường Main Street, Dickinson viết 1,700 bài thơ,

thường là trên

những mẩu giấy, hay ở phía sau một tờ hóa đơn mua thực phẩm, chỉ một

dúm được

xuất bản khi bà con sống, và như thế, kể như vô danh. Theo như kể lại,

thì bà

thường tặng, give, thơ, cho bạn bè và láng giềng thường là kèm với

những cái bánh,

những thỏi kẹo, do bà nướng, đôi khi thả chúng xuống từ 1 cửa sổ phòng,

trong 1

cái giỏ. Cái thói quen gói những bài thơ

thành 1 tập nho nhỏ, fasciles, cho thấy, có thể bà cho rằng thơ thì

trình ra được,

presentable, nhưng hầu hết thơ của bà thì đều không đi quá xa cái bàn

viết, ở

trong những ngăn kéo, và chúng được người chị/hay em, khám phá ra, sau

khi

bà mất vào năm 1886, do “kidney failure”. John

Fowles, trong The Aristos: A Self-Portrait in Ideas, Poems...

nhân mùa World Cup 1966, đã đưa ra nhận xét:

Trước Cuộc Truy Hoan

"Bóng đá gồm 22 cây gậy [của tên ăn mày, như các cụ thường nói], đuổi theo một cái âm hộ; cái chày của môn chơi golf là một dương vật cán bằng thép; vua và hoàng hậu trong môn cờ là Laius và Jocasta, mọi chiến thắng đều là một dạng, hoặc bài tiết hoặc xuất tinh." Có thể nói, văn chương nghệ thuật Tây phương bắt đầu, bằng cuộc tranh giành một nàng Hélène de Troie. [Laius là cha, Jocasta là mẹ mà Oedipus bị lời nguyền của con nhân sư, phải giết đi và lấy làm vợ. Jocasta sau treo cổ tự tử, Oedipus tự chọc mắt, làm người mù chống gậy đi lang thang giữa sa mạc]. Bóng đá, môn

chơi của sức mạnh, "thuộc về đàn ông", nhưng đàn ông tới cỡ nào, có lẽ

chỉ mấy ông tiểu thuyết gia, tức chuyên viên về một "hình thức sung mãn

nam tính" (G. Lukacs), mới tưởng tượng nổi. "Bóng đá gồm 22 cây gậy

[của tên ăn mày, như các cụ

thường nói], đuổi theo một cái âm hộ; cái chày của môn chơi golf là một

dương vật

cán bằng thép; vua và hoàng hậu trong môn cờ là Laius và Jocasta, mọi

chiến thắng

đều là một dạng, hoặc bài tiết hoặc xuất tinh." Có thể nói, văn chương nghệ thuật Tây phương bắt đầu, bằng cuộc tranh giành một nàng Hélène de Troie. [Laius là cha, Jocasta là mẹ mà Oedipus bị lời nguyền của con nhân sư, phải giết đi và lấy làm vợ. Jocasta sau treo cổ tự tử, Oedipus tự chọc mắt, làm người mù chống gậy đi lang thang giữa sa mạc]. Nguyên con, như sau: 65 Bởi vì theo

LLosa, mọi xứ sở đều chơi bóng đá, đúng cái kiểu mà họ làm tình. Những

mánh lới,

kỹ thuật này nọ của những cầu thủ, nơi sân banh, đâu có khác chi một sự

chuyển

dịch (translation) vào trong môn chơi bóng đá, những trò yêu đương quái

dị,

khác thường, khác các giống dân khác, và những tập tục ân ái từ thuở

"Hùng

Vương lập nước"- thì cứ thí dụ vậy - lưu truyền từ đời này qua đời khác

tới

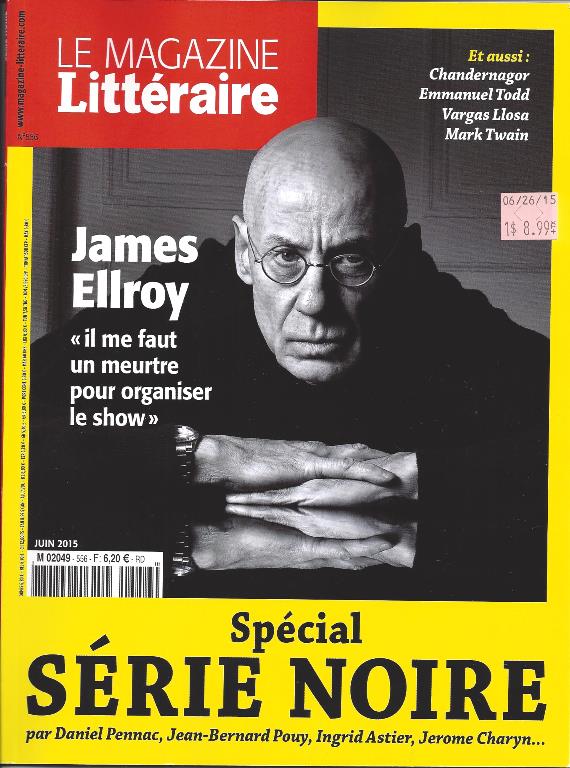

tận chúng ta bi giờ!   James

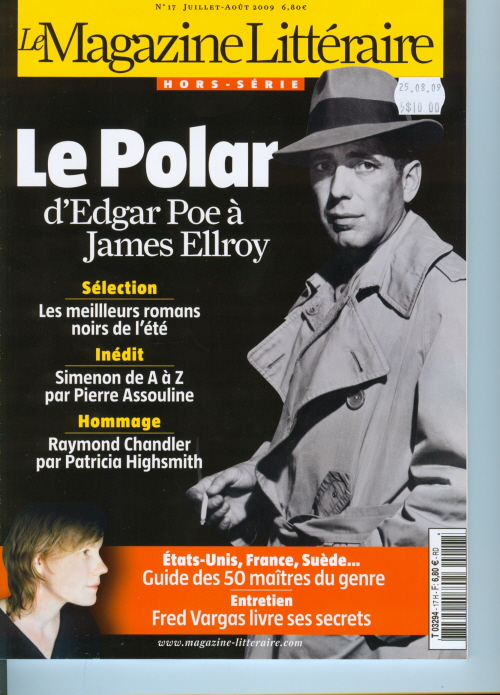

Ellroy, le justicier magnifique par Violaine

Binet "Je

ne

lis plus dorénavant, C'est dans mon sang. On n'apprend pas le gout du

sang à un

tigre. Le tigre a faim, il a besoin de viande. C'est moi le tigre. Je

suis le

tigre du roman noir.”

Tôi đếch đọc nữa. Có sẵn trong máu. Người ta đâu dạy hổ mùi máu. Nó đói, nó cần thịt sống. Tớ là con hổ đó. Tớ là con hổ của tiểu thuyết đen.     Note: Bức hình GGM bị bầm mắt, bạn NL gửi cho, là từ số báo này. V/v cú Vargas Llosa thoi Garcia Marquez, người viết tiểu sử của GM viết: Tình bạn giữa

họ chấm dứt khi Vargas Llosa thoi Garcia Marquez đến bất tỉnh, ở hành

lang một

rạp hát, do GM lăng nhăng với bà vợ của ông. Vargas Llosa phán, đây là

cú đấm nổi

tiếng nhất trong lịch sử Mỹ Châu La Tinh, “the most famous punch in the

history

of Latin America”, nhưng không đưa ra lý do.  Số báo này

có quá nhiều bài tuyệt cú mèo. Bài về Giáo Đường, của Faulkner, khui ra

một chi

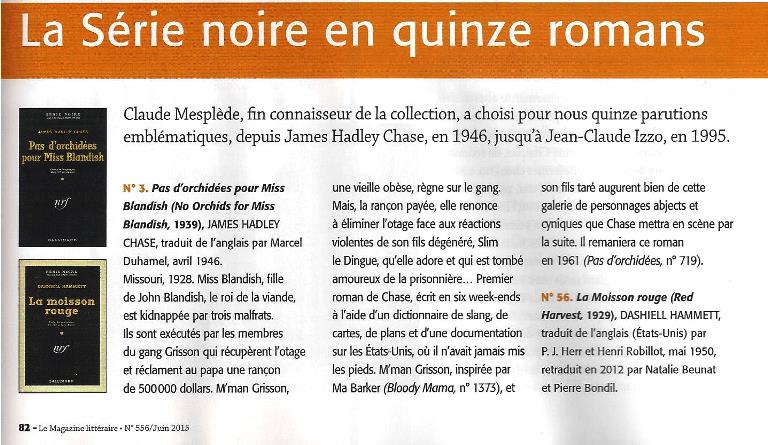

tiết thật thú vị: Cuốn Pas d'Orchidées

pour Miss Blandish (1938) của J.H. Chase, đã từng được Hoàng Hải

Thuỷ phóng

tác thành Trong vòng tay du đãng, là

từ Giáo Đuờng bước thẳng qua. Cái từ

tiểu thuyết đen, roman noir, của Tây không thể nào dịch qua tiếng Mẽo,

vì sẽ bị

lầm, "đen là da đen", nhưng có một từ thật là bảnh thế nó, đó là

"hard boiled", dur à cure,

khó nấu cho sôi, cho chín. Cha đẻ của từ này, là Raymond Chandler, cũng

một

hoàng đế tiểu thuyết đen!

Bài viết về Chandler của nữ hoàng trinh thám Mẽo, Patricia Highsmith cũng tuyệt. Rồi bài trả lời phỏng vấn của Simenon, trong đó, ông phán, số 1 thế kỷ 19 là Gogol, số 1 thế kỷ 20 là Faulkner, và cho biết, cứ mỗi lần viết xong một cuốn tiểu thuyết là mất mẹ nó hơn 5 kí lô, và gần một tháng ăn trả bữa mới bù lại được! Bài trò chuyện với tân nữ hoàng trinh thám Tây Fred Vargas cũng tuyệt luôn: "Tôi chơi trò thanh tẩy" ["Je joue le jeu de la catharsis"]. Viết trinh thám mà là thanh tẩy! (1) Nhưng nhận xét sau đây, theo tôi, thật đáng đồng tiền bát gạo, về tiểu thuyết trinh thám đen Mẽo. Nó chắc chắn sẽ trở thành một lời tiên tri cho văn học Việt Nam. Phillipe Larbo & Olivier Barrot, trong cuốn Một cuộc du ngoạn văn học: Những lá thư từ Mẽo quốc, đã đưa ra nhận xét, chính cái khí hậu khởi đầu của nó, mới đáng kể: Khi ban bố luật quái quỉ, cứ rượu là cấm đó, nhà nước đã biến tất cả những người công dân của nó trở thành những kẻ phạm pháp. Và chăng, cái luật đó lại được hỗ trợ bởi chính cái gọi là lịch sử lập quốc chinh phục Viễn Tây, cứ thấy đất là cướp, thấy da đỏ là thịt, là hãm, là đưa đi cải tạo, kinh tế mới... Chính cái khí hậu ăn cướp đó, mở ra tiểu thuyết trinh thám đen Mẽo! (1) Bạn để ý coi, nó có giống y chang cái cảnh ăn cướp Miền Nam? (2) EXILES To be exiled

is not to disappear but to shrink, to slowly or quickly get smaller and

smaller

until we reach our real height, the true height of the self. Swift,

master of

exile, knew this. For him exile was the secret word for journey. Many

of the

exiled, freighted with more suffering than reasons to leave, would

reject this

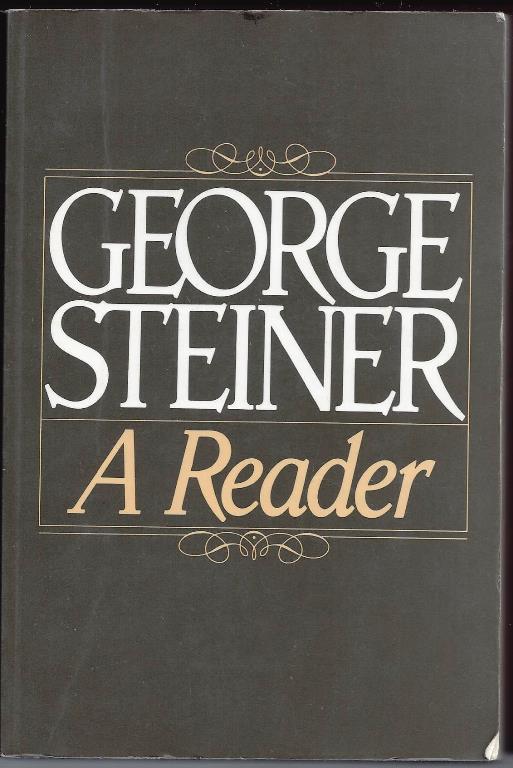

statement. Mọi văn chương cưu mang trong nó “cái gọi là” lưu vong, cho dù nhà văn, hoặc là đi bụi vào lúc đôi mươi hay là chẳng bao giờ rời khỏi nhà! Có lẽ hai tên lưu vong đầu tiên, thì là A Đam và E Và. Điều này khỏi bàn cãi, nhưng nó lại dấy lên vài câu hỏi, không lẽ thằng nào, con nào đều là… "lưu vong"? “Đàng nào” thì cũng là Đàng Trong, đếch có Đàng Ngoài? Nói rõ hơn, cái ý niệm Đất Lạ có vài cái lỗ hổng ở trong nó? Đất Lạ là 1 thực thể địa lý mang tính khách quan? Hay là 1 cấu trúc tinh thần luôn trong dòng chảy?  Epilogue [1961; from The Death of Tragedy] I want to

end this book on a note of personal recollection rather than of

critical

argument. There are no definite solutions to the problems I have

touched on.

Often allegory will illuminate them more aptly than assertion.

Moreover, I

believe that literary criticism has about it neither rigor nor proof.

Where it

is honest, it is passionate, private experience seeking to persuade.

The three

incidents I shall recount accord with the threefold possibility of our

theme:

that tragedy is, indeed, dead; that it carries on in its essential

tradition

despite changes in technical form; or, lastly, that tragic drama might

come

back to life. In some obscure village in central

Poland,

there was a small synagogue. One night, when making his rounds, the

Rabbi

entered and saw God sitting in a dark comer. He fell upon his face and

cried

out: 'Lord God, what art Thou doing here?' God answered him neither in

thunder

nor out of a whirlwind, but with a small voice: 'I am tired, Rabbi, I

am tired

unto death.' The bearing of this

parable on our theme, I take it, is this: God

grew weary of the savagery of man. Perhaps He was no longer able to

control it

and could no longer recognize His image in the mirror of creation. He

has left

the world to its own inhuman devices and dwells now in some other comer

of the universe

so remote that His messengers cannot even reach us. I would suppose

that He

turned away during the seventeenth century, a time which has been the

constant

dividing line in our argument. In the nineteenth century, Laplace

announced

that God was a hypothesis of which the rational mind had no further

need; God

took the great astronomer at his word. But tragedy is that form of art

which

requires the intolerable burden of God's presence. It is now dead

because His

shadow no longer falls upon us as it fell on Agamemnon or Macbeth or

Athalie. Cao Huy Khanh Sơ khảo 15 năm văn xuôi miền nam

Khởi Hành

Linh tinh

Milan Kundera có còn quan hệ gì không? Does Milan Kundera Still Matter? (Atlantic July/August 2015) GS Kinh

Tế, “Trùm” Trang "Việt Xì Tốp Đi

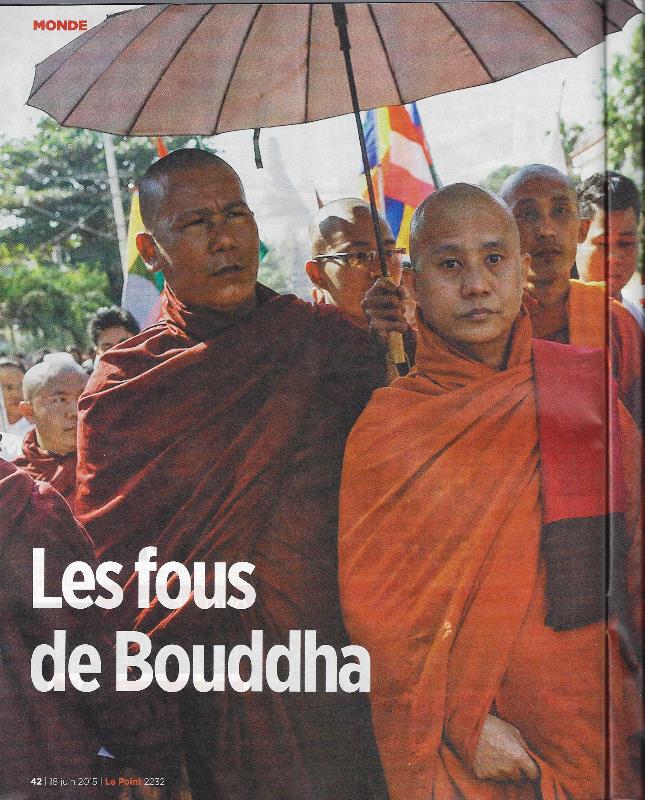

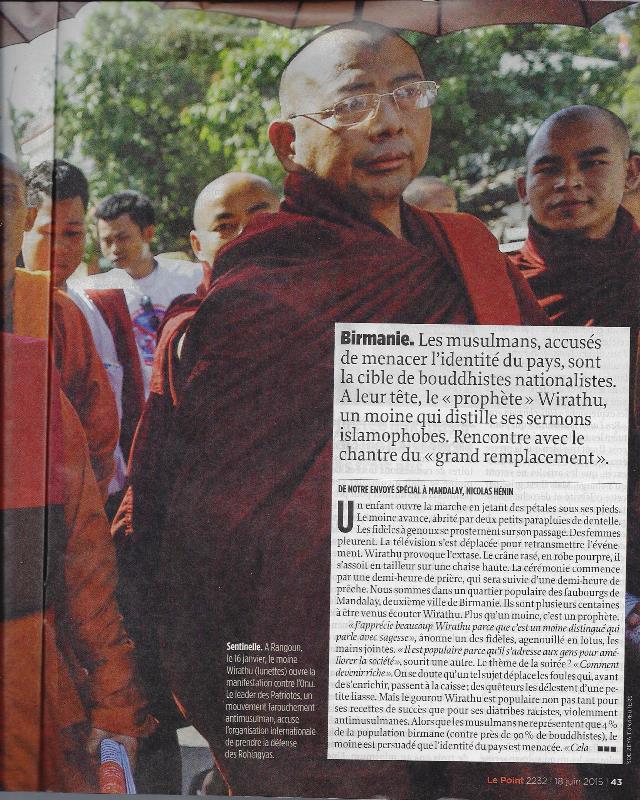

Thôi", dịch nhảm quá. Obituary: Christopher LeeNoblesse oblige  Ui chao, lại nhớ đến Phật Giáo Miền Nam ngày nào! Không khùng, nhưng đa số trốn lính, hoặc phò VC!   Cuốn trên,

GCC đọc hồi mới ra hải ngoại, thời gian đi bán bảo hiểm nhân thọ. Mượn

thư viện,

nhờ đó biết đến Fowles. Sau tìm hoài, không gặp. Bữa nay, gặp, đúng

ngày Father's

Day, có tí tiền còm ghé tiệm sách cũ. Gấu có thuổng 1 ý trong cuốn này,

trong

bài viết về World Cup. Nay, sẽ post

nguyên con! Lạ, là tay này

rất mê Anh Môn. Và cuốn Anh Môn, bản tiếng Anh, để kế ngay cuốn trên,

để chờ

GCC cầm lên. Gấu có mấy bản tiếng Tẩy, chỉ thèm bản tiếng Anh! Miền Đã Mất

The Lost Domaine  John

Fowles

1926-2005

Nhà văn Anh, tác giả

Người

Đàn Bà của Viên Trung Uý Pháp,

The French Lieutenant's Woman, và nhiều cuốn nổi tiếng khác như The

Collector, Kẻ

Sưu Tập, Magus… Lỗ Giun [Wormholes, tập tiểu luận] đã mất vì bịnh tim

ngày 5 Nov, thọ 79 tuổi.

[Hình Torontor Star] Tác phẩm

Go on, run

away, but

you would be far safer if you stayed at home.The Collector The Aristos The Magus The French Lieutenant's Woman Poems The Elbony Tower Shipwreck Daniel Martin Islands The Tree The Enigma of Stonehenge Mantissa A Short Story of Lyme Regis A Maggot Lyme Regis Camera. * Trong Tựa đề cho những bài thơ, Foreword to the Poems, John Fowles cho rằng cơn khủng hoảng của tiểu thuyết hiện đại, là do bản chất của nó, vốn bà con với sự dối trá. Đây là một trò chơi, một thủ thuật; nhà văn chơi trò hú tim với người đọc. Chấp nhận bịa đặt, chấp nhận những con người chẳng hề hiện hữu, những sự kiện chẳng hề xẩy ra, những tiểu thuyết gia muốn, hoặc (một chuyện) có vẻ thực, hoặc (sau cùng) sáng tỏ. Thi ca, là con đường ngược lại, hình thức bề ngoài của nó có thể chỉ là trò thủ thuật, rất ư không thực, nhưng nội dung lại cho chúng ta biết nhiều, về người viết, hơn là đối với nghệ thuật giả tưởng (tiểu thuyết). Một bài thơ đang nói: bạn là ai, bạn đang cảm nhận điều gì; tiểu thuyết đang nói: những nhân vật bịa đặt có thể là những ai, họ có thể cảm nhận điều gì. Sự khác biệt, nói rõ hơn, là như thế này: thật khó mà đưa cái tôi thực vào trong tiểu thuyết, thật khó mà lấy nó ra khỏi một bài thơ. Go on, run away... Cho dù chạy đi đâu, dù cựa quậy cỡ nào, ở nhà vẫn an toàn hơn. Nhi [Nhi, không phải Nhị, theo như 1 bài viết của Hồ Nam, về Mai Thảo, trên Gió O. Tên 1 cô gái, Gấu đã lầm, là Nhị Hà, sông Hồng]

John Fowles,

nhà văn Anh, khi được hỏi tại sao ông lại gọi cuộc phỏng vấn ông, là

một

"Unholy Inquisition" (Pháp Đình Tà Ma), đã trả lời: Thì cũng giống một

chiến sĩ bị mật vụ Đức Gestapo, hay một kẻ vô thần bị mấy ông phán quan

của

Chúa, tra hỏi. Đâu có ai muốn "hoạn nạn" như vậy! John

Fowles, trong The Aristos: A Self-Portrait in Ideas, Poems...

nhân mùa World Cup 1966, đã đưa ra nhận xét: "Bóng đá gồm 22 cây gậy

[của tên ăn mày, như các cụ thường nói], đuổi theo một cái âm hộ; cái

chày của môn chơi golf là một dương vật cán bằng thép; vua và hoàng hậu

trong môn cờ là Laius và Jocasta, mọi chiến thắng đều là một dạng, hoặc

bài tiết hoặc xuất tinh." Có thể nói, văn chương nghệ thuật Tây phương

bắt đầu, bằng cuộc tranh giành một nàng Hélène de Troie.

[Laius là cha, Jocasta là mẹ mà Oedipus bị lời nguyền của con nhân sư, phải giết đi và lấy làm vợ. Jocasta sau treo cổ tự tử, Oedipus tự chọc mắt, làm người mù chống gậy đi lang thang giữa sa mạc]. Trước Cuộc Truy Hoan

Bóng đá, môn

chơi của sức mạnh, "thuộc về đàn ông", nhưng đàn ông tới cỡ nào, có lẽ

chỉ mấy ông tiểu thuyết gia, tức chuyên viên về một "hình thức sung mãn

nam tính" (G. Lukacs), mới tưởng tượng nổi. Nguyên con, như sau: 65 Games are

far more important to us, and in far deeper ways, than we like to

admit. Some

psychologists explain all the symbolic values we attach to games, and

to losing

and winning them, in Freudian terms. Football consists of twenty-two

penises in

pursuit of a vagina; a golf club is a steel-shafted phallus; the chess

king and

queen are Laius and Jocasta; all winning is a form either of evacuation

or of

ejaculation; and so on. Such explanations mayor may not have value in

discussing the origin of the game. But for most players and spectators

a much more

plausible explanation is the Adlerian one, that a game is a system for

achieving superiority. It is moreover a system (like money getting)

that is to

a certain extent a human answer to the inhuman hazard of the cosmic

lottery; to

be able to win at a game compensates the winner for not being able to

win outside

the context of the game. This raison d' être

of the game is most clearly seen in the games of pure chance; but many

other

games have deliberate hazards; and even in games technically free of

hazards the

bounce, the lie, the fly in the eye exist. The evil is this: from

instituting

this system of equalizing hazard man soon moves to regarding the winner

in it

as not merely lucky but in some way excellent; just as he now comes to

regard

the rich man as in some way intrinsically excellent. * Le Grand MeaulnesThe girl at the Grand PalaisAnh Môn

|