|

Lê Công Định shared Đặng Bích Phượng's post.Đất nước ngày càng vô pháp càng đòi hỏi nhiều hơn một thể chế mới vừa tôn trọng nhân quyền của người dân, vừa gầy dựng lại tinh thần trọng pháp bởi nhà cầm quyền trước tiên. Chế độ cộng sản hiện tại đã đánh mất cả hai yếu tố đó, nên không xứng đáng tiếp tục ở vị thế cầm quyền một cách chính danh nữa. Note: Những hình ảnh xứ Mít như hiện nay, là ý nghĩa của cái từ "Tháng Tư Đen". Tháng Tư Đen nghĩa là gì, là như thế.http://www.diendan.org/viet-nam/30-thang-tu

OUR VIETNAM WAR NEVER ENDED

By Viet Thanh Nguyen LOS ANGELES-THURSDAY; the last day of April, is the 40th anniversary of the end of my war. Americans call it the Vietnam War, and the victorious Vietnamese call it the American War. In fact, both of these names are misnomers, since the war was also fought, to great devastation, in Laos and Cambodia, a fact that Americans and Vietnamese would both rather forget. In any case, for anyone who has lived through a war, that war needs no name. It is always and only "the war," which is what my family and I call it. Anniversaries are the time for war stories to be told, and the stories of my family and other refugees are war stories, too. This is important, for when Americans think of war, they tend to think of men fighting "over there:' The tendency to separate war stories from immigrant stories means that most Americans don't understand how many of the immigrants and refugees in the United States have fled from wars-many of which this country has had a hand in. Although my family and other refugees brought our war stories with us to America, they remain largely unheard and unread, except by people like us. Compared with many of the four million Vietnamse in the diaspora, my family has been lucky. None of my relatives can be counted among the three million who died during the war, or the hundreds of thousands who disappeared at sea trying to escape by boat. But our experiences in coming to America were difficult. When I first came to this country, at age 4, I was taken from my parents and put into a household of American strangers who were supposed to care for me while my parents got on their feet. I remember a small apartment, or maybe a mobile home, and a young couple who did not know what to do with me. I was sent on to a bigger house, a family with children, who asked me how to use chop-sticks. I'm sure they meant to be welcoming, but I was perplexed and disappointed in myself for not knowing how to use them. As for Vietnam, it is both familiar and strange. I heard much about it as I grew up in San Jose, Calif., in a Vietnamese enclave where I ate Vietnamese food, went to a Vietnamese church, studied the Vietnamese language, and heard Vietnamese stories, which were always about loss and pain. My parents and everyone I knew had lost homes, wealth, relatives, country and peace of mind. Letters and photographs in Par Avion envelopes, trimmed in red and blue, would arrive bearing words of poverty and hunger and despair. My parents had left behind my older, adopted sister, whom I knew only through one black-and-white photograph, a beautiful girl with a lonely expression. I didn't remember her at all. I didn't remember the grandparents who passed away one by one, two of whom I never met because they had stayed in the north while my parents had fled to the south as teenagers in 1954. My father would never see his mother again, and not see his father for 40 years. My mother would never see her parents again, and not see her sisters for 20 years. And the violence they sought to escape caught up with them. My father and mother opened a grocery store and were shot and wounded in a robbery on Christmas Eve, when I was 10 years old. I was watching cartoons, waiting for them to come home. My brother took the phone call. When he told me what had happened I did not cry, and he shouted at me for not crying. I would not return to Vietnam for 27 years because I was frightened of it, as so many of the Vietnamese in America were. I found the Vietnamese in America both intimate and alien, but Vietnam itself was simply alien. How I remembered it was through American movies and books, all of them in the English language that I had decided was mine at some unspoken, unconscious level. I heard broken English all around me, spoken by refugees whom I couldn't help but see through American eyes: fresh off the boat, foreign, laughable, hateful. That was not me. I could not see how I could live a life in two languages equally well, so I decided to master one and ignore the other. But in mastering that language and its culture, I learned too well how Americans viewed the Vietnamese. I watched "Apocalypse Now" and saw American sailors massacre a sampan full of civilians and Martin Sheen shoot a wounded woman in cold blood. I watched "Platoon" and heard the audience cheering and clapping when the Americans killed Vietnamese soldiers. These scenes, although fictional, left me shaking with rage. I knew that in the American imagination I was the Other, the Gook, the foreigner, no matter how perfect my English, how American my behavior. In my mostly white high school, the handful of Asian students clustered together in one corner for lunch and even called ourselves the Asian Invasion and the Yellow Peril. Such stories are common among the Vietnamese people I know. For many, like the southern Vietnamese veterans who will not find the names of their more than 200,000 dead comrades on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, the war has not ended. That is because they are not "Vietnam veterans" in the American mind. Our function is to be grateful for being defended and rescued, and many of us indeed are. The United States welcomed hundreds of thousands of refugees from Southeast Asia in the years after the war. You would be hard pressed to find a more patriotic bunch than us, from the law professor who helped write the Patriot Act to the scientist who designed a bunker-buster bomb for the Iraq war. You can also count among our numbers many veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. But at the same time these Vietnamese Americans fought for America, they also struggled to carve out their own space in this country. They built their own Vietnam War Memorial in Orange County, Calif., home of Little Saigon, the largest Vietnamese community outside of Vietnam. It tells a more inclusive story, featuring a statue of an American and Vietnamese soldier standing side by side. Every April, thousands of refugees and veterans and their children gather here to tell their own story and to commemorate what they call Black April. This Black April, the 40th, is a time to reflect on the stories of our war. Some may see our family of refugees as living proof of the American dream-my parents are prosperous, my brother is a doctor who leads a White House advisory committee, and I am a professor and novelist. But our family story is a story of loss and death, for we are here only because the United States fought a war that killed three million of our countrymen (not counting over two million others who died in neighboring Laos and Cambodia). Filipinos are here largely because of the Philippine-American War, which killed more than 200,000. Many Koreans are here because of a chain of events set off by a war that killed over two million. We can argue about the causes for these wars and the apportioning of blame, but the fact is that war begins, and ends, over here, with the support of citizens for the war machine, with the arrival of frightened refugees fleeing wars we have instigated. Telling these kinds of stories, or learning to read, see and hear family stories as war stories, is an important way to treat the disorder of our military- industrial complex. For rather than being disturbed by the idea that war is hell, this complex thrives on it. Cuộc chiến Mít chẳng bao giờ chấm dứt. Sai. Một cách nào đó, nó đã chấm dứt, cùng với sự lộ diện của Tẫu, như 1 con Quỉ Chuồng Heo, trong "Y sĩ Đồng Quê", của Kafka, và sự hiện hữu thê thảm của 1 xứ Mít đang trên mép bờ huỷ diệt, với Họa Biển, Họa Đất [vụ Bô Xít, thí dụ], họa "Cửu Long Cạn Dòng..." như hiện nay. Cái cách mà tay VTN này đọc/coi Tận Thế Là Đây, làm nhớ đến Đinh Linh, khi anh viết về nó, và cho đăng trên Guardian, và Tin Văn, đã chỉ ra, đọc không tới, khi viện dẫn tay làm phim này, Coppola, thật hãnh diện phán, Tận Thế Là Đây “là” Việt Nam, và GCC thêm vô: Ông ta chỉ ra trái tim của bóng đen, “là” Hà Nội, theo đúng ý nghĩa của Conrad, khi viết The Heart Of Darkness: Lũ Bắc Kít, khi ăn cướp Miền Nam chúng nghĩ là chúng khai hóa Miền Nam, bằng cái văn minh đồng bằng Sông Hồng, nhưng hóa ra là Trái Tim của Bóng Đen, ‘là’ Hà Nội. DL cũng 1 thứ Mít lớn lên ở Mẽo, và cũng 1 cách nhìn Mẽo như VTN, và cũng gốc gác Ngụy, như nhau. Có 1 thiểu số Mẽo gốc Mít gốc Nam Kít/Ngụy như họ, khi tố cáo sự coi khinh những sắc dân thiểu số vs da trắng, mà hậu quả là cú giết hại Cớm Mẽo da trắng, như vừa xẩy ra, và nhìn như thế, thì cái hình ảnh “Black Lives Matter” còn làm nhớ tới những cái sọ da đen treo lủng lẳng trên những cây sào trong Trái Tim của Bóng Đen. http://tanvien.net/TG_TP/khai_huyen_doi_tra.html http://tanvien.net/Souvenir/ky_niem_3.html

Chim tươi sống, Thượng Đế ‘order’, là vặt lông, làm thịt, 'sắp

kèo rượu', [tương tiến tửu] liền tù tì Cứ tội ác gì cũng đổ cho Mẽo hết, đến một lúc nào đó Coppola, chẳng may vớ được cục tiếng Anh, [bài viết đăng trên Guardian của DL], bèn, như Hitler, vặc lại, nếu không có Lò Thiêu làm sao có nước Israel, nếu chúng tao không nhảy vô Miền Nam, làm sao chúng mày có lý do để mà đánh cho Mỹ cút Ngụy nhào, giải phóng Miền Nam, thống nhất đất nước, qui về một mối, cùng nhìn về… Trái tim Hà Nội? Bởi vì,

không có người Mẽo can thiệp vô Việt Đây là

thảm kịch Việt Ý nghĩa

"nó là Việt Không

phải tự nhiên nhiều người, coi đây là đỉnh cao sự nghiệp Coppola: Như

Littell, tác giả Les Bienveillantes,

khi muốn nhập thân vào Cái Ác: (1) Gấu

Cái cảnh cáo: Mi cứ viết hoài như thế này, thì mi cũng khùng thôi. Kissinger,

phải đến chót đời, mới nhận ra sự lì lợm, không chấp nhận một biện pháp

nửa vời, a compromise, cho cuộc chiến của Miền Bắc, tuy nhiên ông ta không

làm sao mà hiểu được, lời nguyền 'Nàng là giống Rồng, Ta là giống Tiên', và

giấc mơ ‘giao lưu hòa giải’, thống nhất đất nước, nhằm huỷ diệt lời nguyền,

ngay từ khi… chưa có giống Mít, đó là cái phần đẹp

nhất của cuộc chiến, đúng như ý muốn của Chúa, khi Ngài OK cho giống Mít

có mặt ở trên thế gian này. Nhưng

hỡi ơi, chính Người cũng không thể tưởng tượng ra được "Trái Tim Là Bóng

Đen" của Hà Nội nó khủng tới cỡ nào! Đến Ông

Giời mà cũng còn lầm, nữa là! Theo

nghĩa đó, Anne Applebaum mới phán, đến ngay Thượng Đế mà cũng không thể

tưởng tượng ra được Tây Phương chiến thắng Cuộc Chiến Tranh Lạnh, khi bà

vinh danh Koestler. Đó là

công lao của chỉ 1 cuốn sách: Đêm Giữa Ngọ.

ABSALOM, ABSALOM! Absalom, Absalom! Tôi

biết hai loại nhà văn. Một, ám ảnh của họ là cuộc diễn biến của chữ, verbal

procedure, một, việc làm, work, và đam mê của con người. Loại thứ nhất, cực

điểm của họ, là ‘nghệ sĩ thuần tuý’. Loại kia, may mắn thay, được ban cho

những cái nón như là “sâu thẳm” [profound], “nhân bản”, human, rất nhân bản.

Trong số này, còn có những người ở giữa, nghĩa là tu tập cả niềm vui lẫn

đức hạnh của cả hai loại trên. Trong số những tiểu thuyết gia vĩ đại nhất,

Joseph Conrad là người cuối cùng, có lẽ, đã quan tâm đến những thủ tục của

một tiểu thuyết như trong số phận và nhân cách của những nhân vật của ông.

Người cuối cùng, cho đến khi Faulkner xuất hiện trên

sàn diễn. Nhà hát

là Miền Absalom, Absalom! có thể sánh với Âm thanh và Cuồng

nộ, và tôi không biết, có lời vinh danh nào cao hơn thế nữa, về nó!

Borges Tuyệt! Khen

1 tác phẩm của Faulkner, bằng 1 tác phẩm khác, cũng của Faulkner! Đâu có

thứ võ công nào khác, để mà đánh bại Ngài, ngoài võ công của chính Ngài! Khi cuốn sách của cái tay này, được Pulitzer, rồi lại thấy anh ta khoe, Sebald là my"hero", GCC mừng quá. Hóa ra đồ dởm, và thay vì, Cảm Tình Viên, thì Gấu bèn dùng đúng cái từ dành cho nó: Tên Phản Thùng. Cái tên dịch bài viết này, lại càng 1 tên phản thùng. Tên này, như đã từng lèm bèm, đệ tử của Cao Bồi, bố là Ngụy, giám thị Chu Văn An, được Ngụy cho du học rồi làm Cớm cho VC tại Paris. Không phải tự nhiên mà hắn dịch bài viết nói lên quan điểm của tác giả cuốn sách. Cũng 1 cách chạy tội, như cả 1 lũ nằm vùng làm mất Miền Nam. V/c cuộc chiến Mít. Trên 40 năm rồi, đã bắt đầu cho thấy nguyên nhân đích thực của nó. Trước hết, nó không phải là 1 cuộc chiến giải phóng của 1 đất nước cựu lục địa của Pháp. Cái sự lệ thưộc đến trở thành bồi Tẫu của Bắc Bộ Phủ như bây giờ, cho thấy, đây là cuộc chiến giữa các thế lực đế quốc ngoại bang, Pháp, Mẽo, và Tẫu "nằm vùng", đúng như Solz, là người đầu tiên, ngay từ những ngày 1975, phán, trong 1 chương trình trả lời phỏng vấn văn học trên 1 đài truyền hình Pháp. Ông bị Octavio Paz chê, hiểu sai, nhưng bây giờ, lịch sử cho thấy, Solz cực kỳ sáng suốt. Làm sao mà ông ta nhận ra được 1 cách sớm sủa như thế? TTT, khi từ giã gia đình, khăn gói quả mướp, mang theo 10 ngày đường lương thực lao động cải tạo, nói với thằng em, GCC, Miền Bắc sẽ bị chấn thương nặng nề vì chiến thắng này. Có điều, ông không làm sao nhìn ra, vào những ngày ngay sau 30 tháng Tư 1975, xứ Mít sẽ có nguy cơ, bị "biến mất" vì chiến thắng này đỉnh cao chói lọi này, mới đúng "con cào cào, chuồn chuồn, châu chấu"! Cái “thuật ngữ”, “Tháng Tư Đen”, lúc thoạt đầu được đám Miền Nam hải ngoại sử dụng, nó có 1 ý nghĩa hạn hẹp và bị những tên phản thùng như lũ này, vin vào đó, để viết nhảm, đúng ra phải được dùng để chỉ xứ Mít như là hiện nay, bắt đầu từ ngày 30 Tháng Tư 1975. Như GCC đã từng viết, "Bức Tường Lòng", của Mít, như Bức Tường Bá Linh của Đức, chỉ bắt đầu có, kể từ ngày 30 Tháng Tư 1975. Không phải trước đó. Cuốn tiểu thuyết Kẻ Phản Thùng, đúng ra - vẫn "đúng ra" - người viết phải là Cao Bồi, giả như anh được Bắc Bộ Phủ cho di tản tiếp, tiếp tục nằm vùng ở Mẽo. Một số những nhà hoạt động ở trong nước, mà GCC không tiện nêu tên, vì sợ làm họ khốn đốn thêm với VC, đã nhìn ra sự kiện, như GCC trình bày, trên đây. Cái cực kỳ thê lương khốn kiếp của cuộc chiến Mít, là không thể nào có 1 hồi ức nào về nó, kể cả những hồi ức tù của đám Ngụy, mà đa số là đồ dởm. Không thể hồi ức, tưởng niệm, kể cả ở lũ VC! Một tên già, tay đầy máu Ngụy, như tên NN, thí dụ, cái hành động, cái ý thức "tự kiểm" [mauvaise conscience] cao nhất của hắn ta, là cởi mặt nạ, nhìn 1 tên Mẽo, kẻ thù ngày nào của hắn. Hắn đâu biết -tất nhiên làm ra vẻ đếch biết - Ngụy là gì? Nếu nói về thái độ chính trị, thì cứ tạm gọi như vậy, tay này thua xa Nam Lê, tác giả Con Thuyền, The Boat. Nhớ, Sến có lần ngỏ ý khen chế độ Ngụy, nhưng cảnh cáo liền, đừng có nghĩ ta có ý vực dậy cái xác chết, cái thây ma đó Giả như Sến muốn như thế, cũng vô phương. Cái chế độ Ngụy là chế độ đẹp nhất của xứ Mít, và sở dĩ như thế, là do nền của nó là 1 thiên đàng, tức 1 Miền Nam, 1 Sài Gòn, đúng như nó được gọi, 1 hòn ngọc Viễn Đông, và vẫn sở dĩ được như thế, không phải vì nó nguy nga to tát, bề thế hơn Bangkok, như tên ngu đần Thái Dúi đi 1 đường chọc quê trên Bi Bì Xèo, mà là do khí hậu được thiên nhiên ưu đãi, do dân tình hiền hòa, do cái gọi là mentalité, hay văn minh, vivilisé, của dân Nam Bộ, và còn do thằng Tẩy không hề có phân biệt đối xử với lũ cô lô nhần Nam Kít, điều này, 1 số nhà văn nổi tiếng, như Graham Greene, hay Maugham, xác nhận, như Tin Văn đã từng trưng ra, như là những bằng chứng có thiệt. Một khi Bắc Kít ăn cướp được, nó trở thành bửn, y hệt xứ Bắc Kít, như nó từng bửn, do cái độc, cái ác gây nên. Kafka phán, con người bị đá đít ra khỏi thiên đàng, nhưng không vì thế mà thiên đàng bị hủy diệt. Than ôi, Ngài chết sớm quá. Nếu giờ này, mà còn sống, chắc Ngài phải làm 1 cú hiệu đính, như thói quen cực bửn, của đám nhà văn Bắc Kít! Sài Gòn có phải

là 'Hòn ngọc Viễn Đông'?

Trương Thái Du Gửi tới

BBC Tiếng Việt từ Sài Gòn

Cái tên Hòn Ngọc Viễn Đông, là Tẩy ban cho Sài Gòn, và quả đúng như thế, và sở dĩ được như thế, thì vì nhiều lý do, trong có cái gọi là "mentalité" của dân Miền Nam, và cái gọi là “văn minh” của Tẩy. Tẩy đối xử với dân Miền Nam ngang hàng, không phân biệt. Điều này được những nhà văn, thí dụ hai đấng, là Graham Greene, trong "Ways of Escape" đã có những dòng ca ngợi thần sầu về Sài Gòn, và Maugham, trong bài viết về Huế, có trên Tin Văn. Và quả đúng là quá khứ không thể nào lập lại, và điều này phần lớn là do Bắc Kít. Cái độc, cái ác của chúng làm biến đổi xã hội Miền Nam đến tận gốc rễ, không làm sao gượng lại được nữa.

HUẾ HUE

IS A pleasant little town with something of the leisurely

air of a cathedral city in the West of England, and though

the capital of an empire it is not imposing. It is built on both

sides of a wide river, crossed by a bridge, and the hotel is one

of the worst in the world. It is extremely dirty, and the food is

dreadful; but it is also a general store in which everything is provided

that the colonist may want from camp equipment and guns, women's

hats and men's reach-me-downs, to sardines, pate de foie gras, and

Worcester sauce; so that the hungry traveler can make up with tinned

goods for the inadequacy of the bill of fare. Here the inhabitants

of the town come to drink their coffee and fine in the evening and

the soldiers of the garrison to play billiards. The French have

built themselves solid, rather showy houses without much regard for

the climate or the environment; they look like the villas of retired

grocers in the suburbs of Paris.

The French carry France to their colonies just as the English carry England to theirs, and the English, reproached for their insularity, can justly reply that in this matter they are no more singular than their neighbors. But not even the most superficial observer can fail to notice that there is a great difference in the manner in which these two nations behave towards the natives of the countries of which they have gained possession. The Frenchman has deep down in him a persuasion that all men are equal and that mankind is a brotherhood. He is slightly ashamed of it, and in case you should laugh at him makes haste to laugh at himself, but there it is, he cannot help it, he cannot prevent himself from feeling that the native, black, brown, or yellow, is of the same clay as himself, with the same loves, hates, pleasures and pains, and he cannot bring himself to treat him as though he belonged to a different species. Though he will brook no encroachment on his authority and deals firmly with any attempt the native may make to lighten his yoke, in the ordinary affairs of life he is friendly with him without condescension and benevolent without superiority. He inculcates in him his peculiar prejudices; Paris is the centre of the world, and the ambition of every young Annamite is to see it at least once in his life; you will hardly meet one who is not convinced that outside France there is neither art, literature, nor science. But the Frenchman will sit with the Annamite, eat with him, drink with him, and play with him. In the market place you will see the thrifty Frenchwoman with her basket on her arm jostling the Annamite housekeeper and bargaining just as fiercely. No one likes having another take possession of his house, even though he conducts it more efficiently and keeps it in better repair that ever he could himself; he does not want to live in the attics even though his master has installed a lift for him to reach them; and I do not suppose the Annamites like it any more than the Burmese that strangers hold their country. But I should say that whereas the Burmese only respect the English, the Annamites admire the French. When in course of time these peoples inevitably regain their freedom it will be curious to see which of these emotions has borne the better fruit. The Annamites are a pleasant people to look at, very small, with yellow flat faces and bright dark eyes, and they look very spruce in their clothes. The poor wear brown of the color of rich earth, a long tunic slit up the sides, and trousers, with a girdle of apple green or orange round their waists; and on their heads a large flat straw hat or a small black turban with very regular folds. The well-to-do wear the same neat turban, with white trousers, a black silk tunic, and over this sometimes a black lace coat. It is a costume of great elegance. But though in all these lands the clothes the people wear attract our eyes because they are peculiar, in each everyone is dressed very much alike; it is a uniform they wear, picturesque often and always suitable to the climate, but it allows little opportunity for individual taste; and I could not but think it must amaze the native of an Eastern country visiting Europe to observe the bewildering and vivid variety of costume that surrounds him. An Oriental crowd is like a bed of daffodils at a market gardener's, brilliant but monotonous; but an English crowd, for instance that which you see through a faint veil of smoke when you look down from above on the floor of a promenade concert, is like a nosegay of every kind of flower. Nowhere in the East will you see costumes so gay and multifarious as on a fine day in Piccadilly. The diversity is prodigious. Soldiers, sailors, policemen, postmen, messenger boys; men in tail coats and top hats, in lounge suits and bowlers, men in plus fours and caps, women in silk and cloth and velvet, in all the colors, and in hats of this shape and that. And besides this there are the clothes worn on different occasions and to pursue different sports, the clothes servants wear, and workmen, jockeys, huntsmen, and courtiers. I fancy the Annamite will return to Hue and think his fellow countrymen dress very dully. Somerset Maugham: The Skeptical Romancer Tháng Tư Đen, nghĩa là thế này này, lũ khốn hiểu ra chưa? NQT Hai cựu học sinh

trường Hà Nội-Amsterdam gặp nhau bàn chuyện họp khoá.

LikeShow more reactions

CommentShare Kẻ

Phản Thùng

Ghost Hunter by Eleanor Wachtel ELEANOR WACHTEL: Sebald writes a requiem for a generation in The Emigrants, an extraordinary book about memory, exile, and death. The writing is lyrical, the mood elegiac. These are stories of absence and displacement, loss and suicide, Germans and Jews, written in the most evocative, haunting, and understated way. The Emigrants is variously called a novel, a narrative quartet, or simply unclassifiable. How would you describe it? Sebald viết kinh cầu cho 1 thế hệ trong Di Dân, một cuốn sách khác thường về hồi ức, lưu vong, và chết chóc. Cách viết thì trữ tình, giọng điệu thì bi ai. Đây là những câu chuyện về trống vắng và đổi dời, trôi lạc, “xểnh nhà ra thất thổ” - displacement, mất mát, và tự tử, Đức và Do Thái, viết bằng một cách nức nở, gợi nhớ, ám ảnh, và kìm giữ, cố làm cho nó chìm xuống - không 1 tí cường điệu - Di dân có nhiều cái tên, một cuốn tiểu thuyết, một tứ tấu khúc mang tính tự sự -chắc là giống Tứ Tấu Khúc của GCC? - hay giản dị mà phán, đếch làm sao gọi bằng 1 cái tên nào, không thể xếp loại. Ông nghĩ sao? W. G. SEBALD: It's a form of prose fiction. I imagine it exists more frequently on the European continent than in the Anglo-Saxon world, i.e., dialogue plays hardly any part in it at all. Everything is related round various corners in a periscopic sort of way. In that sense it doesn't conform to the patterns that standard fiction has established. There isn't an authorial narrator. And there are various limitations of this kind that seem to push the book into a special category. But what exactly to call it, I don't know. GCC tính đọc Kẻ Phản Thùng, nhưng THNM, hay, chắc là do sự kiện, tác giả của nó coi Sebald là hero, thế là, thay vì đọc Kẻ Phản Thùng, thì giới thiệu Sebald, qua bài phỏng vấn ông, do Wachtel thực hiện, và bài essay của Dyer, về ông.

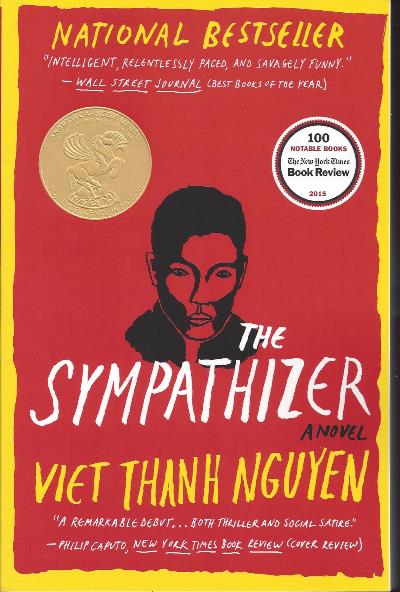

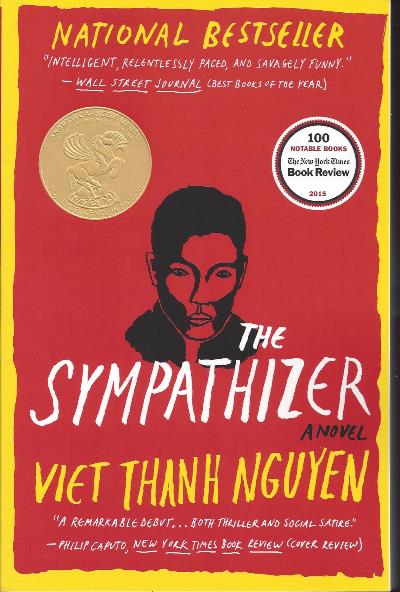

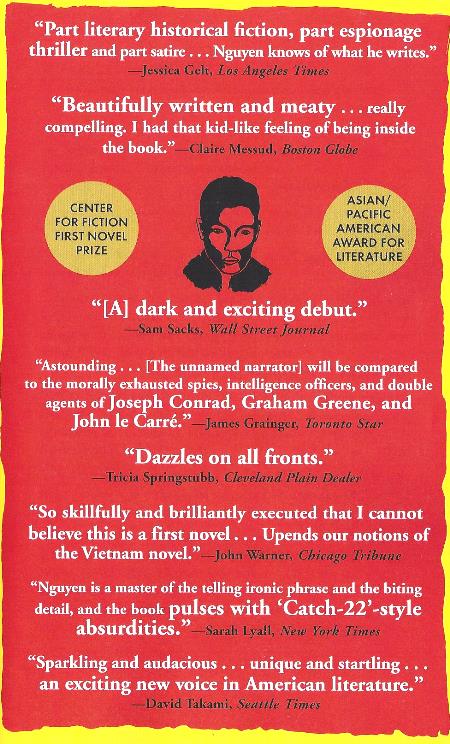

John Freeman: The Sympathizer and Nothing Ever Dies are published fast on the heels of one another, I wonder if you could talk about how their thinking was linked. Viet Thanh Nguyen: Both of these books come out of a line of me wanting to deal with Vietnam, and more broadly, the question of war and memory in general. The ideas in Nothing Ever Dies grew slowly—I worked on it for over a decade, but the book itself I wrote in a year. I threw out all the articles I’d written and then wrote it from scratch after I had finished The Sympathizer. Some of those ideas had filtered into the fiction—but all the work of the fiction worked itself into the writing of the nonfiction. The ambition in the back of my mind—I may not be there yet—is that I would love to be able to write fiction like criticism and criticism like fiction. I think of W.G. Sebald—a hero of mine—I can’t tell the difference in his work, whether it is fiction or nonfiction, it all feels like literature. So as I was writing these books closely together, I was doing the best to incorporate criticism into the fiction, and fiction into the criticism, so with The Sympathizer I was hoping to construct a narrator who could say dramatically very critical things, but who wouldn’t be restricted as an academic to source his beliefs. In Nothing Ever Dies, I couldn’t find a way to find a sense of humor into that book, but I really did try to take everything I had learned from the novel—narrative rhythm, for example—even working my basest unsaid feelings into the very shape of the thing. One of things I want both books to do is to move the reader both emotionally and intellectually. TV giới thiệu bài viết mới có được, về ông, nhân mới xuống phố. Trong bài viết, trong cuốn trên, tác giả nối kết Sebald, với vụ không kích, và với Thomas Bernhard. Bài viết của Dyer về Sebald xoáy vào cuốn mà Gấu mê nhất của ông, Về lịch sử tự nhiên về huỷ diệt, “On the natural history of destruction”. TV “phải” mua cuốn sách, để “phải” đi 1 đường về Sebald, là vì bài viết này, chưa kể bài viết về “Cuộc Tình Bỏ Đi” của Scott Fitzgerald, “Tender Is the Night” [cuốn “Một Chủ Nhật Khác” là cùng dòng với nó] On the Natural History of Destruction goes to the epicenter of ruination, examining the Allied bombardment of German cities in the Second World War. Given the scale of the calamity, Sebald asks, why have German writers been so silent about it? How had it come about that 'the sense of unparalleled national humiliation felt by millions in the last years of the war had never really found verbal expression, and that those directly affected by the experience neither shared it with each other nor passed it on to the next generation'? Geoff Dyer: W. G. Sebald, Bombing and Thomas Bernhard Viet Thanh Nguyen coi Sebald là “hero” của ông, vì cách viết pha trộn, nào giả tưởng, nào phê bình, hầm bà làng, như anh viết, và, nếu như thế thôi, thì, theo GCC, đọc chưa tới Sebald! Cõi văn của Sebald, như của Kertesz, là 1 cõi đồng vọng cho “hồn thiêng” Lò Thiêu, đúng như từ của Viện Hàn Lâm ban cho ông. Đồng Vọng cho Hồn Thiêng Lò Thiêu http://www.tanvien.net/cn/cn_kertesz_medium.html Ông ta viết như một hồn ma. W.G. Sebald, Bombing and Thomas Bernhard

The first

thing to be said about W G. Sebalds books is that they always had a posthumous

quality to them. He wrote - as was often remarked - like a ghost. He was

one of the most innovative writers of the late twentieth century; and

yet part of this originality derived from the way his prose felt as if

it had been exhumed from the nineteenthGeoff Dyer Điều đầu tiên được nói về những cuốn sách của Sebald, là chúng đều có cái air di cảo. Ông ta viết, như một hồn ma. Là 1 trong những nhà văn làm mới số 1 của hậu thế kỷ 20, tuy nhiên, 1 phần của cái uyên nguyên, là từ cái cách ông viết văn xuôi, như thể chúng được lôi lên từ cái xác thế kỷ 19! John Freeman: The Sympathizer and Nothing Ever Dies are published fast on the heels of one another, I wonder if you could talk about how their thinking was linked. Viet Thanh Nguyen: Both of these books come out of a line of me wanting to deal with Vietnam, and more broadly, the question of war and memory in general. The ideas in Nothing Ever Dies grew slowly—I worked on it for over a decade, but the book itself I wrote in a year. I threw out all the articles I’d written and then wrote it from scratch after I had finished The Sympathizer. Some of those ideas had filtered into the fiction—but all the work of the fiction worked itself into the writing of the nonfiction. The ambition in the back of my mind—I may not be there yet—is that I would love to be able to write fiction like criticism and criticism like fiction. I think of W.G. Sebald—a hero of mine—I can’t tell the difference in his work, whether it is fiction or nonfiction, it all feels like literature. So as I was writing these books closely together, I was doing the best to incorporate criticism into the fiction, and fiction into the criticism, so with The Sympathizer I was hoping to construct a narrator who could say dramatically very critical things, but who wouldn’t be restricted as an academic to source his beliefs. In Nothing Ever Dies, I couldn’t find a way to find a sense of humor into that book, but I really did try to take everything I had learned from the novel—narrative rhythm, for example—even working my basest unsaid feelings into the very shape of the thing. One of things I want both books to do is to move the reader both emotionally and intellectually. Gấu biết đến Sebald là qua 1 bài viết của Sontag. Bà coi ông, 1 thứ nhà văn của nhà văn. Viet Thanh Nguyen coi ông là “hero” của mình, và rất mê lối viết trộn lẫn nhiều thể loại, phê bình, văn xuôi, hồi tưởng…. Gấu đọc Sebald khác hẳn, một kẻ săn hồn ma, như chính ông tự nhận, hay, với GCC, một lương tâm của nước Đức hậu chiến. Vả chăng tuy trộn lẫn nhiều thể loại, trong khi viết giả tưởng, nhưng với những bài viết đúng là phê bình, hay biên khảo, Sebald xuất hiện như 1 vị quan tòa, và văn của ông, là thứ phán đoán, truy xét, hỏi tội, Judgment. TV giới thiệu bài viết mới có được, về ông, nhân mới xuống phố. Trong bài viết, trong cuốn trên, tác giả nối kết Sebald, với vụ không kích, và với Thomas Bernhard. Bài viết của Dyer về Sebald xoáy vào cuốn mà Gấu mê nhất của ông, Về lịch sử tự nhiên về huỷ diệt, “On the natural history of destruction”. TV “phải” mua cuốn sách, để “phải” đi 1 đường về Sebald, là vì bài viết này, chưa kể bài viết về “Cuộc Tình Bỏ Đi” của Scott Fitzgerald, “Tender Is the Night” [cuốn “Một Chủ Nhật Khác” là cùng dòng với nó] On the Natural History of Destruction goes to the epicenter of ruination, examining the Allied bombardment of German cities in the Second World War. Given the scale of the calamity, Sebald asks, why have German writers been so silent about it? How had it come about that 'the sense of unparalleled national humiliation felt by millions in the last years of the war had never really found verbal expression, and that those directly affected by the experience neither shared it with each other nor passed it on to the next generation'? Geoff Dyer: W. G. Sebald, Bombing and Thomas Bernhard Câu hỏi trên, 1 cách nào đó, có thể áp dụng vào Miền Bắc xứ Mít: Tại sao chúng vờ luôn Công Ơn Trời Biển của Thiên Triều? Bài phỏng vấn W.G. Sebald do Eleanor

Wachtel thực hiện, Tin Văn quả có nhắc tới, qua cái tên là Kẻ săn hồn ma,

Ghost Hunter. Bài mới, chắc là bài cũ, nhưng thêm phần nhận xét của Wachtel.

Trò chuyện với W.G. Sebald: Bài này trên The New Yorker online, Tin Văn có trích dịch, trong bài Tưởng niệm Sebald Ghost Hunter Eleanor Wachtel [CBC Radio’s Writers & Company on April 18, 1998]: Sebald viết một kinh cầu cho một thế hệ, trong Di dân, The Emigrants, một cuốn sách khác thường về hồi nhớ, lưu vong, và chết chóc. Cách viết thì trữ tình, lyrical, giọng bi khúc, the mood elegiac. Ðây là những câu chuyện về vắng mặt, dời đổi, bật rễ, mất mát, và tự tử, người Ðức, người Do Thái, được viết bằng 1 cái giọng hết sức khơi động, evocative, ám ảnh, haunting, và theo cách giảm bớt, understated way. Di dân có thể gọi bằng nhiều cái tên, một cuốn tiểu thuyết, một tứ khúc kể, a narrative quartet [Chắc giống Tứ Khúc BHD của GCC!], hay, giản dị, không thể gọi tên, sắp hạng. Ông diễn tả như thế nào? WG Sebald: EW: Một nhà phê bình gọi ông là kẻ săn hồn ma, a ghost hunter, ông có nghĩ về mình như thế? WGS: Ðúng như thế. Yes,

I do. I think it’s pretty precise…

Mua xon. Thần sầu! Những khoảnh khắc tạm hoãn án tử hình! Tớ là 1 tên Bắc Kít không có niềm tin Ky Tô - đúng là 1 đại ân hận - nhưng rất am hiểu, uyên bác, thấu đáo, về Phán Xét Cuối Cùng!

Người Què Gánh Tội

Trên thế giới, có, và luôn luôn có, 36 người què, còn được gọi là 36 vì công chính, mà sứ mệnh của họ, là, biện minh thế giới, trước Thượng Đế. Họ là những tên què gánh tội, Lamed Wufniks. Họ không biết nhau, và rất ư là nghèo khổ. Nếu có 1 tên biết rằng mình là tên què gánh tội, là bèn lập tức, ngỏm củ tỏi. Và một người khác, có lẽ ở đâu đó trên thế giới, thế chỗ anh ta. Không có 36 tên cà chớn này, là liền lập tức, Thượng Đế xóa sổ thế giới. http://www.tanvien.net/Viet/Borges_Imaging_Beings.html Kẻ Phản Thùng ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

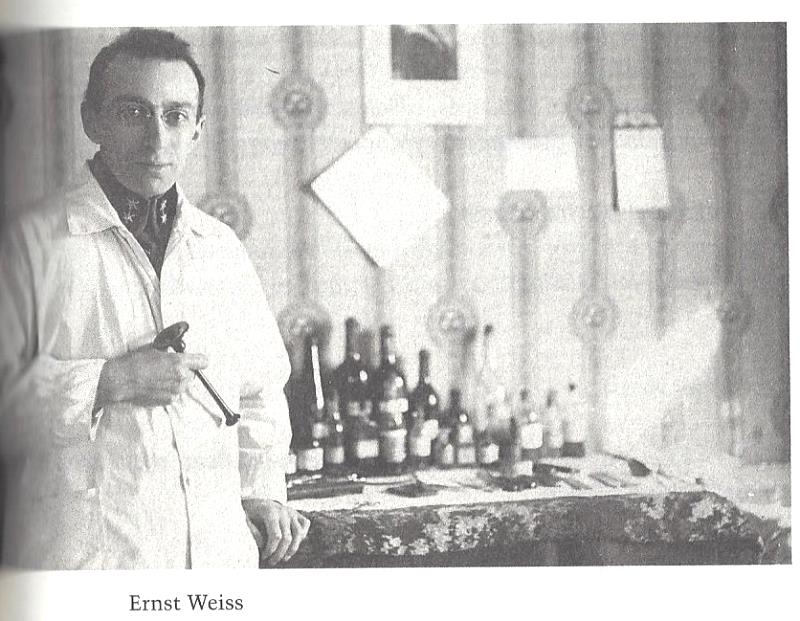

Many of the events in this novel did happen, although I confess to taking some liberties with details and chronology. For the fall of Saigon and the last days of the Republic of Vietnam, I consulted David Butler's TheFall of Saigon, Larry Engelmann's Tears Before the Rain, James Fenton's "The Fall of Saigon;' Dirck Halstead's "White Christmas;' Charles Henderson's Goodnight Saigon, and Tiziano Terzanis Giai Phong! The Fall and Liberation of Saigon. I am particularly indebted to Frank Snepp's important book Decent Interval, which provided the inspiration for Claude's flight from Saigon and the episode with the Watchman. For accounts of South Vietnamese prisons and police, as well as Viet Cong activities, I turned to Douglas Valentine's The Phoenix Program, the pamphlet We Accuse by Jean-Pierre Debris and Andre Menras, Truong Nhu Tang's A Vietcong Memoir and an article in the January 1968 issue of Life. Alfred W. McCoy's A Question of Torture was crucial for understanding the development of American interrogation techniques from the 1950s through the war in Vietnam, and their extension into the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. For the reeducation camps, I made use of Huynh Sanh Thong's To Be Made Over, Jade Ngoc Quang Huynh's South Wind Changing, and Tran Tri Vus Lost Years. As for the Vietnames resistance fighters who attempted to invade Vietnam, a small exhibit in the Lao People's Army History Museum in Vientiane display their captured artifacts and weapons. While those fighters have been largely forgotten, or simply never known, the inspiration for the Movie can hardly be a secret. Eleanor Coppola's documentary Hearts of Darkness and her Notes: The Making ofApocalypse Now provided many insights, as did Francis Ford Coppola's commentary on the Apocalypse Now DVD. These works were also helpful: Ronald Bergan's Francis Ford Coppola: Close Up Jean-Paul Chaillet and Elizabeth Vincent's Francis Ford Coppola, Jeffrey Chowns : Hollywood Auteur: Francis Coppola, Peter Cowie's The Apocalypse Now Book and Coppola: A Biography. Michael Goodwin and Naomi Wise's On the Edge: The Life and Times of Francis Coppola, Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill's Francis Ford Coppola: Interviews, and Michael Schumacher's Francis Ford Coppola: A Filmmaker's Life. I also drew on articles by Dirck Halstead, 'Apocalypse Finally", Christa Larwood, "Return to Apocalypse Now", Deirdre McKay and Padmapani L. Perez, "Apocalypse Yesterday Already! Ifugao Extras and the Making of Apocalypse Now" Tony Rennell, "The Maddest Movie Ever"; and Robert Sellers, "The Strained Making of Apocalypse Now." The exact words of others were occasionally important as well, in particular those of To Huu, whose poems appeared in the Viet Nam News article "To Huu: The People's Poet"; Nguyen Van Ky, who translated the proverb "The good deeds of Father are as great as Mount Thai Son," available in the book Viet Nam Exposé, the 1975 edition of Fodor's Southeast Asia; and General William Westmoreland, whose ideas concerning the Oriental's view of life and its value were given in the documentary Hearts and Minds by director Peter Davis. Those ideas are attributed here to Richard Hedd. Finally, I am grateful to a number of organizations and people without whom this novel would not be the book that it is. The Asian Cultural Council, the Bread Loaf Writers Conference, the Center for Cultural Innovation, the Djerassi Resident Artists Program, the Fine Arts Work Center, and the University of Southern California gave me grant, residencies, or sabbaticals that facilitated my research or writing. My agents, Nat Sobel and Julie Stevenson, provided patient encouragement and wise editing, as did my editor, Peter Blackstock. Morgan Entrekin and Judy Hottensen were enthusiastic supporters, while Deb Seager, John Mark Boling, and all the staff of Grove Atlantic have worked hard on this book. My friend Chiori Miyagawa believed in this novel from its beginning and tirelessly read the early drafts. But the people to whom I owe the greatest debt are, as ever, my father, Joseph Thanh Nguyen, and my mother, Linda Kim Nguyen. Their indomitable will and sacrifice during the war years and after made possible my life and that of my brother, Tung Thanh Nguyen. He has been ever supportive, as has his wonderful partner, Huyen Le Cao, and their children, Minh, Luc, and Linh. As for the last words of this book, I save them for the two who will always come first: Lan Duong, who read every word, and our son, Ellison, who arrived right on time. [VTN] Theo GCC, "nguồn" của cuốn Kẻ Phản Thùng, chính là điệp vụ, mission, của Cao Bồi, khi anh nghĩ là Bắc Kít sẽ cho anh di tản vào ngày 30 Tháng Tư 1975, và tiếp tục nằm vùng trong thế giới Ngụy ở hải ngoại. Anh đã chẳng cho di tản vợ con ư? Cái cú giúp bạn quí Trần Kim Tuyến lên máy bay ở trên mái nhà 1 căn cứ của XỊA, theo GCC, là cũng để "dùng vào việc" sau đó, nhưng đến giờ chót Bắc Bộ Phủ phán, NO, vì sợ lộng giả thành chân, anh sẽ thực sự trở cờ. Bắc Kít huỷ điệp vụ của PXA, và, thay vì di tản, thì đi học tập cải tạo. Chúng chỉ muốn thịt tôi, nhưng tôi chọc chúng đủ giận, nhưng không quá mức để chúng không có cớ giết tôi, PXA chẳng đã từng trả lời cái tay phỏng vấn ông, trong bài viết trên tờ Người Nữu Ước? Thành ra cuốn Kẻ Phản Thùng, chính là giấc mơ di tản của Cao Bồi đã được thực hiện qua 1 cuốn tiểu thuyết. Trong lời cám ơn, VTN không nhắc tới PXA, kể như 1 thiếu sót lớn, theo GCC. Đọc lời cảm ơn, ảnh hưởng lớn lên VTN, là Trái Tim Của Bóng Đen, qua tiểu thuyết, và qua phim, khi Coppola chuyển thể nó, Tận Thế Là Đây. Bạn đọc TV chắc còn nhớ câu phán thần sầu của Coppola: Tận Thế Là Đây, LÀ, Việt Nam? Nếu như thế, thì Kẻ Phản Thùng, cũng LÀ, Việt Nam! VTN nhắc tới Tố Hữu, đúng ra, nên nhắc tới Trần Dần: Sartre (Situations, I) nhắc tới "ý hướng tính", coi đây là tư tưởng cơ bản của hiện tượng luận: "Husserl đã tái tạo dựng (réinstaller) sự ghê rợn và sự quyến rũ vào trong những sự vật. Ông tái tạo thế giới của những nghệ sĩ và của những nhà tiên tri: Ghê sợ, thù nghịch, nguy hiểm trùng trùng, với những bến cảng, nơi trú ẩn của ân sủng và tình yêu." Tôi đã lầm, khi nghĩ, chẳng bao giờ người ta lại được đọc những trang sách tuyệt vời, về Hà-nội. Có thể là do một câu thơ và viễn ảnh khủng khiếp nó gây ra ở nơi tôi. "Chỉ thấy mưa sa trên mầu cờ đỏ" (Trần Dần), câu thơ như một "Apocalypse Now" (Tận Thế Là Đây), không phải chỉ riêng cho Hà-nội. Làm sao mà thi sĩ lại nhìn thấy suốt cuộc chiến sau đó, không phải chiến thắng, mà huỷ diệt, một thành phố, rồi cùng với nó, là biểu tượng của cả một dân tộc ?

CBS's Cameraman & UPI's Radiophoto

Operator

Gấu: Nhớ xừ luỷ không? The Vietnam War (or American War, as

it is called in Vietnam) was long and bloody. The Vietnamese estimate

that between 1954 and 1975 about one million communist fighters and

four million civilians died. According to US numbers, nearly 60,000

American soldiers died or went missing in action, 300,000 were injured

and about 250,000 South Vietnamese soldiers were killed. Cuộc chiến Mít khủng khiếp còn

ở điểm này: Báo chí tha hồ đưa tin. Cái mánh loại trừ là bản năng

tự vệ của mọi chuyên viên Vụ da cam đang nóng, nóng dây

chuyền tới những vụ khác, như thảm sát Mậu Thân, mà những tài liệu

từ một diễn đàn trên lưới cho thấy, không phải VC mà là CH [Cộng Hoà]

gây nên. Rồi ngày nào, là vụ pháo kích vô một trường học ở Cai Lậy,

cũng pháo CH, không phải hoả tiễn VC. Độc giả Tin Văn đã biết về Sebald,

qua bài tưởng niệm ông, khi ông qua đời

sau một vụ đụng xe. Cuốn Lịch sử tự nhiên về huỷ diệt, cũng là

do một sự ngạc nhiên quái dị liên quan tới Đồng Minh uýnh nhau với Nazi:

Trong thời Đệ Nhị Chiến, 131 thành phố và đô thị là mục tiêu ăn bom

của Đồng Minh, nhiều nơi biến thành bình địa. Sáu trăm ngàn thường

dân bị chết, gấp đôi con số thương vong của Mẽo. Bẩy triệu rưởi thường

dân Đức không còn nhà ở. Sebald ngạc nhiên tự hỏi, tại làm sao mà lịch

sử lại vờ đi một sự kiện như thế, nhất là ở nơi ký ức văn hoá của chính

nước Đức? Trong những lời ca ngợi cuốn sách

lạ kỳ của ông, có: Trong bài viết Không Chiến và Văn Chương, Air War and Literature, ông có giải thích về cái sự im hơi bặt tiếng, của hồi ức văn hoá Đức: Họ coi đây là một điều cấm kỵ, một vết thương, vết nhục ở trong gia đình, [a kind of taboo like a shameful family secret]. Cao Bồi, Bạn Gấu Nhà Văn Cựu chủ [Time] viết về nhân viên cũ. (1) DIED.

Pham Xuan An, 79, Viet Cong colonel who worked during the Vietnam War as

a highly respected journalist for TIME while spying for the communists—a double

life kept secret until the mid-'80s; in Ho Chi Minh City. The first Vietnamese

to become a staff correspondent for a [Từ trần.

Phạm Xuân Ẩn, 79 tuổi, đại tá Việt Cộng, trong chiến tranh Việt Nam, là một

ký giả rất được kính trọng của tờ Time, cùng lúc còn làm công tác gián điệp

cho Cộng Sản - một cuộc sống kép được giữ kín cho tới giữa thập niên 1980,

tại Thành Phồ Hồ Chí Minh. Người Việt Tẫu có câu: PXA biết, nhưng không biết,

cái không thể nào biết: Ông xa Đất Bắc lâu quá, đã mấy đời rồi,

ăn cơm Miền Nam, ị ra cứt Miền Nam cũng đã mấy đời rồi, trong cứt

không còn một tí Bắc Kít nào hết, nhưng trái tim ông hoàn toàn

là Bắt Kít, một thứ Bắc Kít tuyệt vời, từ đó, là cái chân lý tuyệt

vời, thống nhất đất nước, biến cả nước thành một Miền Nam tuyệt vời. Năm học

Đệ Nhất

Có một lần ông kể chuyện, về mấy anh Tây mũi lõ, ở bên chánh quốc, thất nghiệp, đói rã họng, bèn kiếm cách xuống tầu tới Đông Dương, tới Hà Nội, không phải để kiếm việc làm, thiếu gì, nhưng mà là để làm “cái bang”, mỗi khi cần tí tiền, là ra nhà hàng Godard, lấy cái nón trên đầu xuống, lật lên, xin tiền đám Mít quí phái, và đám Tây Đầm. Lũ Tây Đầm ngượng lắm, vừa thấy cái nón lật lên, là thẩy tiền liền. Thấy "đường được", là tếch. Nhất định không chịu kiếm việc làm. Thế mới thú. Đám Mẽo làm hùng hục, chỉ mãi đến khi quá chán cuộc chiến Mít, mới nghĩ ra trò này: Ăn xin thay vì làm việc! Liệu Cao Bồi biết kỳ tích đó, và anh sử dụng đòn ăn xin - không phải xin đám Bắc Bộ Phủ [mày cho tao bao nhiêu cho xứng công lao gian khổ “nằm Time [Tai, không phải Gai], nếm XO”, làm một tên cớm VC nằm vùng, bán đứng cả một miền đất đã từng cưu mang mấy đời họ Phạm, gốc Hải Dương, Bắc Kít - mà xin mấy anh bạn báo chí cũ, một công đôi ba việc: Tao xin tiền tụi bay, vì tao lỡ lừa tụi bay, và chỉ có cách xin tiền tụi bay, chịu nhục chịu nhã như thế, thì mới phần nào chuộc tội, với cả tụi mày, và cả đồng bào của tao. Tuyệt

chưa?

VIET THANH NGUYEN:

ANGER IN THE ASIAN AMERICAN NOVEL By PAUL TRAN The Vietnam War ended 40 years ago. A new regime rose from the battlefields. Families like mine fled across the Pacific. Many died at sea. Others wish they had. There's no happy ending to this story- not when the losers ceaselessly obsess over their defeat by a people they regard as having little value for human life. This obsession, of course, dominates the ways Americans tell and retell their "intervention" in the Vietnamese peoples' struggle for freedom. It obscures a story about Vietnamese people, their triumphs and tragedies, by placing the United States, its imperial imperatives, its altruism and delusional exceptionalism, at the center of the narrative. But Viet Thanh Nguyen's shimmering debut novel, The Sympathizer, calls our attention back to the war's primary actors. It opens a complex world where no one is on the "right side" of history. Leaping with lyrical verve, each page turns to a unique and hauntingly familiar voice that refuses to let us forget what people are capable of doing to each other. In a phone conversation last month, Nguyen and I spoke about writing a novel full of rage against US imperialism, how the Vietnamese can "fuck ourselves just fine;' and the individual in the wake of failed revolutions. Cuộc chiến Việt Nam chấm dứt 40 năm trước đây. Một chính quyền mọc lên từ chiến trường. Những gia đình trong có gia đình tôi bỏ chạy bằng cách vượt biển Thái Bình Dương. Nhiều người chết. Nhiều người khác mong được như vậy. Chẳng có cái kết thúc hạnh phúc cho câu chuyện này – hạnh phúc sao được, khi kẻ thua cay đắng nhận ra rằng, họ thua những kẻ ít tính người hơn họ. Chính cái sự cay đắng, nỗi ám ảnh này, trấn ngự những cách thức mà những người Mỹ kể đi kể lại sự “can thiệp” của họ trong cuộc chiến đấu giành tự do của người Việt. Nó làm u ám câu chuyện về người Việt, chiến thắng và bi kịch của họ, khi để Hoa Kỳ, thái độ cha chú đế quốc, tính vị tha, và chủ nghĩa ngoại lệ hoang tưởng của nó ở trung tâm của tự sự. Nhưng cuốn tiểu thuyết đầu tay tỏa sáng lung linh của Viet Thanh Nguyen, Kẻ Phản Thùng, kéo sự chú tâm của chúng ta trở lại với những diễn viên gốc của cuộc chiến. Nó mở ra một thế giới đa dạng nơi không ai ở “đúng phía” của câu chuyện. Đi 1 đường cao hứng trữ tính, mỗi trang vọng lên 1 giọng nói độc nhất, nhức nhối, quen thuộc, nó từ chối không cho chúng ta quên rằng thì là, những con người dám làm gì với những con người. Trong 1 cú phôn tháng rồi, Nguyen và tôi nói về, viết 1 cuốn sách đầy sự căm phẫn chống lại chủ nghĩa đế quốc của Hoa Kỳ, như thế nào những người Việt có thể ĐM mày, và cá nhân từng con người trong sự trỗi dậy của những cuộc cách mạng thất bại. Paul Tran: Growing up in San Diego, California, which is a setting in your book, I was the only one in my family who could read and write in English. My mother grew up in central Vietnam. She was born in 1954 and came to the United States in 1989 after spending nine years in a Viet Cong prison and being re-educated in the Philippines. I spent much of my childhood trying to find literature about Vietnamese people. It wasn't until I went to college and left home that this dream began to be realized. I want to begin this conversation this way because I have read interviews in which you express a similar sentiment: where you, as a child growing up in the United States, looked for narratives of Vietnam in literature and in Hollywood. One of the reviews of your book from the New York Times says that it "fills a void in the literature, giving voice to the previously voiceless while it compels the rest of us to look at the events of 40 years ago in a new light:' What void do you believe The Sympathizer fills? Viet Thanh Nguyen: I think that when the New York Times Book Review says The Sympathizer gives voice to the voiceless, it is inaccurate. There is, by now, a significant body of Vietnamese American and Vietnamese literature translated into English. The Vietnamese people and Vietnamese Americans have voices. It's simply that Americans as a whole tend not to hear them. Nevertheless, even given that body of writing by Vietnamese and Vietnamese Americans, I do think that The Sympathizer fills a gap in what that literature talks about. When I was imagining the novel into being, I felt that there still wasn't a novel that directly confronts the history of the American war in Vietnam from the Vietnamese American point of view. Much of the Vietnamese literature that's available in translation focuses on the perspective of the Northern Vietnamese or Communist Vietnamese or formerly-Communist Vietnamese. Vietnamese American literature tends to focus on the refugee experience, what happens to the Vietnamese once they come to the United States. We really have to turn to memoirs by first-generation Vietnamese people like Le Ly Hayslip and Mai Elliott to confront the war itself. Even so, what was missing was literature with a more critical take on what the US did in Vietnam. That was the first instinct of the book -I wanted to be very critical of the role of the Americans in Vietnam and not adopt the usual position of Vietnamese Americans, which is either to be grateful to be rescued by Americans, or conciliatory, not directly confrontational in the literature. I was also responding to a lot of Asian American literature, which I read a great deal of be cause that's part of what my research is about. One of the things that characterizes both Vietnamese and Asian American literature is that it's often times not very angry. There's not a lot of rage, at least not in the past few decades. And if there is anger or rage, it has to be directed at the ignorant: the Asian country of origin or Asian families or Asian patriarchs. While all that is important, I sensed a reluctance to be angry at American culture or at the United States for what it has done. That's why, in the book, I adopt a much angrier tone towards American culture and the US. Finally, I didn't want to let anybody off the hook, so the book is also very critical of South Vietnamese culture and politics and Vietnamese communism. Instead of choosing its targets selectively- only being critical of one group-it decides to hold everyone accountable. Đem tiếng nói đến cho người không có tiếng nói. Tờ Điểm Sách Nữu Ước Thời Báo viết thế là không đúng.

Read on for an essay by and interview

with Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of The Sympathizer.

The article first appeared in the New York Times Sunday Review Opinion pages, April 24, 2015. The Q&A first appeared in the Asian American Writers' Workshop's The Margins, on June 29, 2015. OUR VIETNAM WAR NEVER ENDED

By Viet Thanh Nguyen LOS ANGELES-THURSDAY; the last day of April, is the 40th anniversary of the end of my war. Americans call it the Vietnam War, and the victorious Vietnamese call it the American War. In fact, both of these names are misnomers, since the war was also fought, to great devastation, in Laos and Cambodia, a fact that Americans and Vietnamese would both rather forget. In any case, for anyone who has lived through a war, that war needs no name. It is always and only "the war," which is what my family and I call it. Anniversaries are the time for war stories to be told, and the stories of my family and other refugees are war stories, too. This is important, for when Americans think of war, they tend to think of men fighting "over there:' The tendency to separate war stories from immigrant stories means that most Americans don't understand how many of the immigrants and refugees in the United States have fled from wars-many of which this country has had a hand in. Although my family and other refugees brought our war stories with us to America, they remain largely unheard and unread, except by people like us. Compared with many of the four million Vietnamse in the diaspora, my family has been lucky. None of my relatives can be counted among the three million who died during the war, or the hundreds of thousands who disappeared at sea trying to escape by boat. But our experiences in coming to America were difficult. When I first came to this country, at age 4, I was taken from my parents and put into a household of American strangers who were supposed to care for me while my parents got on their feet. I remember a small apartment, or maybe a mobile home, and a young couple who did not know what to do with me. I was sent on to a bigger house, a family with children, who asked me how to use chop-sticks. I'm sure they meant to be welcoming, but I was perplexed and disappointed in myself for not knowing how to use them. As for Vietnam, it is both familiar and strange. I heard much about it as I grew up in San Jose, Calif., in a Vietnamese enclave where I ate Vietnamese food, went to a Vietnamese church, studied the Vietnamese language, and heard Vietnamese stories, which were always about loss and pain. My parents and everyone I knew had lost homes, wealth, relatives, country and peace of mind. Letters and photographs in Par Avion envelopes, trimmed in red and blue, would arrive bearing words of poverty and hunger and despair. My parents had left behind my older, adopted sister, whom I knew only through one black-and-white photograph, a beautiful girl with a lonely expression. I didn't remember her at all. I didn't remember the grandparents who passed away one by one, two of whom I never met because they had stayed in the north while my parents had fled to the south as teenagers in 1954. My father would never see his mother again, and not see his father for 40 years. My mother would never see her parents again, and not see her sisters for 20 years. And the violence they sought to escape caught up with them. My father and mother opened a grocery store and were shot and wounded in a robbery on Christmas Eve, when I was 10 years old. I was watching cartoons, waiting for them to come home. My brother took the phone call. When he told me what had happened I did not cry, and he shouted at me for not crying. I would not return to Vietnam for 27 years because I was frightened of it, as so many of the Vietnamese in America were. I found the Vietnamese in America both intimate and alien, but Vietnam itself was simply alien. How I remembered it was through American movies and books, all of them in the English language that I had decided was mine at some unspoken, unconscious level. I heard broken English all around me, spoken by refugees whom I couldn't help but see through American eyes: fresh off the boat, foreign, laughable, hateful. That was not me. I could not see how I could live a life in two languages equally well, so I decided to master one and ignore the other. But in mastering that language and its culture, I learned too well how Americans viewed the Vietnamese. I watched "Apocalypse Now" and saw American sailors massacre a sampan full of civilians and Martin Sheen shoot a wounded woman in cold blood. I watched "Platoon" and heard the audience cheering and clapping when the Americans killed Vietnamese soldiers. These scenes, although fictional, left me shaking with rage. I knew that in the American imagination I was the Other, the Gook, the foreigner, no matter how perfect my English, how American my behavior. In my mostly white high school, the handful of Asian students clustered together in one corner for lunch and even called ourselves the Asian Invasion and the Yellow Peril. Such stories are common among the Vietnamese people I know. For many, like the southern Vietnamese veterans who will not find the names of their more than 200,000 dead comrades on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, the war has not ended. That is because they are not "Vietnam veterans" in the American mind. Our function is to be grateful for being defended and rescued, and many of us indeed are. The United States welcomed hundreds of thousands of refugees from Southeast Asia in the years after the war. You would be hard pressed to find a more patriotic bunch than us, from the law professor who helped write the Patriot Act to the scientist who designed a bunker-buster bomb for the Iraq war. You can also count among our numbers many veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. But at the same time these Vietnamese Americans fought for America, they also struggled to carve out their own space in this country. They built their own Vietnam War Memorial in Orange County, Calif., home of Little Saigon, the largest Vietnamese community outside of Vietnam. It tells a more inclusive story, featuring a statue of an American and Vietnamese soldier standing side by side. Every April, thousands of refugees and veterans and their children gather here to tell their own story and to commemorate what they call Black April. This Black April, the 40th, is a time to reflect on the stories of our war. Some may see our family of refugees as living proof of the American dream-my parents are prosperous, my brother is a doctor who leads a White House advisory committee, and I am a professor and novelist. But our family story is a story of loss and death, for we are here only because the United States fought a war that killed three million of our countrymen (not counting over two million others who died in neighboring Laos and Cambodia). Filipinos are here largely because of the Philippine-American War, which killed more than 200,000. Many Koreans are here because of a chain of events set off by a war that killed over two million. We can argue about the causes for these wars and the apportioning of blame, but the fact is that war begins, and ends, over here, with the support of citizens for the war machine, with the arrival of frightened refugees fleeing wars we have instigated. Telling these kinds of stories, or learning to read, see and hear family stories as war stories, is an important way to treat the disorder of our military- industrial complex. For rather than being disturbed by the idea that war is hell, this complex thrives on it.

Cuộc chiến Việt Nam của chúng

ta chẳng bao giờ chấm dứt

Viet Thanh Nguyen [Tin Văn sẽ post bản tiếng Anh, sau;

ở đây, nhân bài viết, mà lèm bèm về cuộc chiến, nhân ngày 30 Tháng

Tư năm nay]

Los

Angeles -Thứ Năm, ngày cuối cùng của Tháng Tư, là kỷ niệm lần thứ 40

chấm dứt cuộc chiến của tôi. Người Mỹ gọi nó là Cuộc Chiến Việt và VC

gọi nó là Cuộc chiến Mỹ. Thực sự chẳng có cái tên nào OK cả, [misnomers-

chữ của VTN, “từ” dùng sai, gốc, chắc Tẩy đọc trật, mis-nommer], kể từ

khi nó còn được uýnh, tới mức quá chán, to great devastation, ở Lào và

Căm Bốt, 1 sự kiện mà cả Mẽo lẫn VC cố tình vờ.Trong bất cứ trường hợp, với bất cứ ai đã trải qua nó, cuộc chiến này đếch có tên – GCC biết điều này từ khuya rồi, nên đã đi 1 bài "thần sầu" về nó, để tưởng niệm ông bạn nhiếp ảnh viên UPI, người Nhật, Sawada: Tên của cuộc chiến http://www.tanvien.net/tg/tg07_ten_cua_cuoc_chien.html Khi mới tới Sài-gòn, nhân vật đầu tiên chào mừng, welcome, thằng bé Bắc-kỳ-di-cư-tôi ngày nào, là khách sạn Majestic. Khách

coi bộ quá hăm hở, mấy ngàn con người lôi thôi, lếch thếch, chỉ vì ách

nước vận trời mà hân hạnh được tầu Mỹ chở tới đây. Chưa từng thấy biển,

bị "trấn" ngay cho một chuyến đi suốt chiều dài đất nước. Chưa từng chiêm

ngưỡng thành phố, đụng liền Hòn Ngọc Viễn Đông. Tuy đã từng ghé Cảng

Hải Phòng, những ngày chờ đợi làm thủ tục, đã "kinh qua" Vịnh Hạ Long,

trên những con tầu há mồm trước khi ra Đệ Thất Hạm Đội, nhưng lòng dạ nào

mà ngắm trời ngắm đất. Thiên nhiên hình như cũng hết còn là của họ, như

cọng rơm cọng cỏ, con gà con chó, xó nhà miếng vườn, đành đứt ruột bỏ lại.

Ấy là chưa kể, người lớn trẻ con ói lên ói xuống vì say sóng. Chen chúc,

luồn lách, cậu bé men tới mép tầu. Majestic thấp hơn cậu một chút.

Con tầu như hiểu ý, nghiêng hẳn sang một bên, cậu có thể thò tay với

tới. Lần thực

sự viếng thăm, chỉ ít lâu sau, là để đập phá khách sạn. Thời gian

học lớp đệ ngũ trường Văn Hóa, của thầy Nguyễn Khắc Kham. Vẫn "thói"

bắc không thể bỏ, chọn thầy trước khi chọn trường, chọn lớp. Tiếng

là trường, chỉ một căn hộ trong một con hẻm đường Ngô Tùng Châu gần Ngã

Sáu Sài-gòn. Tiếng là di cư, nhưng chính ở đây, cậu có người bạn Nam-kỳ

đầu tiên. Cũng lần đầu, cậu nghe anh bạn Trí phát âm "tìn thươn", thay

vì tình thương. Con nhà giầu miệt tỉnh, mấy chị em kéo lên Sài-gòn mua

nhà thay vì trọ học. Và phải là một trường Bắc-kỳ. Anh giải thích: ở

dưới đó, anh "số dzách", nhưng ông thầy lắc đầu, không ăn thua gì đâu, so

với đám học trò người bắc. Anh đưa về "khoe" với mấy anh chị em. Cả nhà

đều mến, nhưng phàn nàn với đứa em: bạn mày nói, tụi tao nghe không ra!

Còn thằng bé cứ há hốc mồm, nghe kể về một miền đất, sáng rảo bộ ra quán

cà-phe nơi đầu ngõ, tiện chân ngoáy ngoáy một hố đất nơi con rạch, trưa

về thò tay nhấc lên một con cá. Nhưng hình ảnh "Nam-kỳ nhất" ở nơi cậu, là

từ một cô gái "lai", Bắc-kỳ xa xưa từ hồi nảo hồi nào. Và nó bắt nguồn từ...

Hà-nội! Hồi đó

ở với bà chị họ, nơi ngoại ô Bạch Mai. Một bữa có một ông chú, từ

Sài-gòn ghé. Gọi là chú, vì ngày trước học chung với ông già. Chú

Th. quê Phú Hữu, một làng nằm trên sườn một ngọn đồi, dưới chân núi

Tản. Ngày nhỏ theo bà già từ Thanh Trì, ven sông Hồng, vượt hết cánh

đồng Sơn, đứng từ dưới nhìn lên, những căn nhà lẩn sau đám cây trên đồi.

Bà già chỉ: nhà bà Hàn kia kìa. Gái Thanh Trì thường làm dâu Phú Hữu.

Cậu bé có mấy bà cô ở trên đồi. Trai Phú Hữu thường ra Thanh Trì làm học

trò ông giáo Dực. Ông già và chú Th. học chung lớp. Chú thi rớt, bị bố

la, bỏ xứ Bắc, nhẩy tầu đi một lèo tới Sài-gòn làm giầu. Ông già thi vô

sư phạm, ra làm hiệu trưởng trường tiểu học, mỗi nhiệm sở đẻ một đứa con

làm dấu. Đứa Hải Dương, đứa Lục Yên Châu... Nhiệm sở chót Việt Trì (Vĩnh

Yên), năm 1945, rồi "thôi" luôn. Lần đó

chú Th. ghé chơi trên đường về quê, mang làm quà cho mấy trái xoài,

và dẫn thằng cháu đi mua cho một đôi giầy, vô tình cho nó một thú vui:

đánh thật bóng, rồi thử xem bụi hè phố Hà-nội mất mấy ngày mới làm mờ. Lần gặp lại, là ở Sài-gòn. Ông hỏi:

"Nước nhà độc lập rồi, còn 'dzô' đây làm gì?" Ông hình như lấy làm

tiếc cho thằng con người bạn học. Cộng sản "nòi", bố bị đảng phái thủ

tiêu. Lý lịch "tốt" như thế, bỏ đi thật uổng! Chửi một hồi thấy tội,

ông nhắc lại một vài kỷ niệm, hồi học chung với ông già. Giầu có như

vậy, ông vẫn nhớ, và cười cười, mày chắc cũng đã hưởng qua nhiều lần,

cái thú ngồi giữa đồng làng, làm một trong tứ khoái, rồi "chịn" lên

mặt cỏ tươi. Làng Thanh Trì của tôi, chú chỉ nhớ có vậy. Thú thật! Làng

Thừa Lệnh, quê Chu Tử, kế ngay bên Phú Hữu. Hai người hình như quen nhau,

từ hồi còn nhỏ. Cô bé con chú Th. là "mặc khải" miền nam, Sài-gòn của tôi.

Dây mơ rễ má với Hà-nội, là vậy. "Nới" rộng ra, nó liên can đến cả

một miền đất. Nhiều người bắc chắc còn nhớ cái

váy nâu, cái quần thâm. Vải may xong, nhúng nâu, nhúng bùn, phơi nắng,

cho tới khi cứng như mo cau, mới được xỏ vào người. Lần bà chị đưa

đứa em tới "trình diện" ông chú, người đàn bà miền nam xuất hiện trước

thằng nhỏ Bắc-kỳ, là hình ảnh một cô bé trong bộ bà ba đen, mỏng, mượt,

mát, như... làn da thứ nhì của con người.

Có

lẽ chưa từng có 1 cuốn tiểu thuyết nào được ca ngợi tới chỉ

như cuốn này.

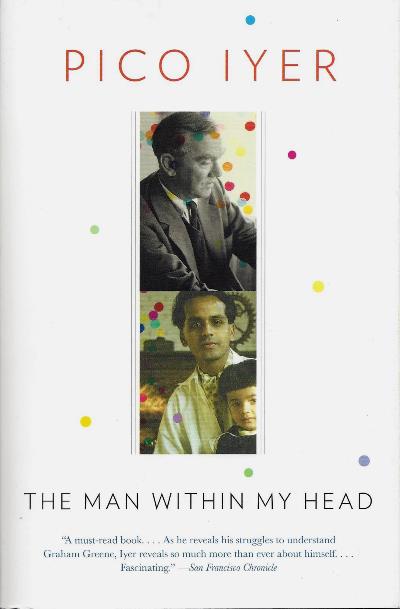

Lượm ra mấy ý thần sầu. Một tân Hâm Liệt, a modern Hamlet, torn by his ability to see all sides, tơi tả rách nát vì khả năng nhìn tất cả các phía - làm nhớ tới vị thần hai mặt Janus PXA. Vọng lên Graham Greene, Conrad, và Kafka. Note: Cái tên Cảm Tình Viên, theo GCC, yếu quá. Phải là Tên Phản Thùng This

Black April, the 40th, is a time to reflect on the stories of our

war. Some may see our family of refugees as living proof of the

American dream-my parents are prosperous, my brother is a doctor

who leads a White House advisory committee, and I am a professor and

novelist. But our family story is a story of loss and death, for we are

here only because the United States fought a war that killed three million

of our countrymen (not counting over two million others who died in neighboring

Laos and Cambodia). Filipinos are here largely because of the Philippine-American

War, which killed more than 200,000. Many Koreans are here because

of a chain of events set off by a war that killed over two million.

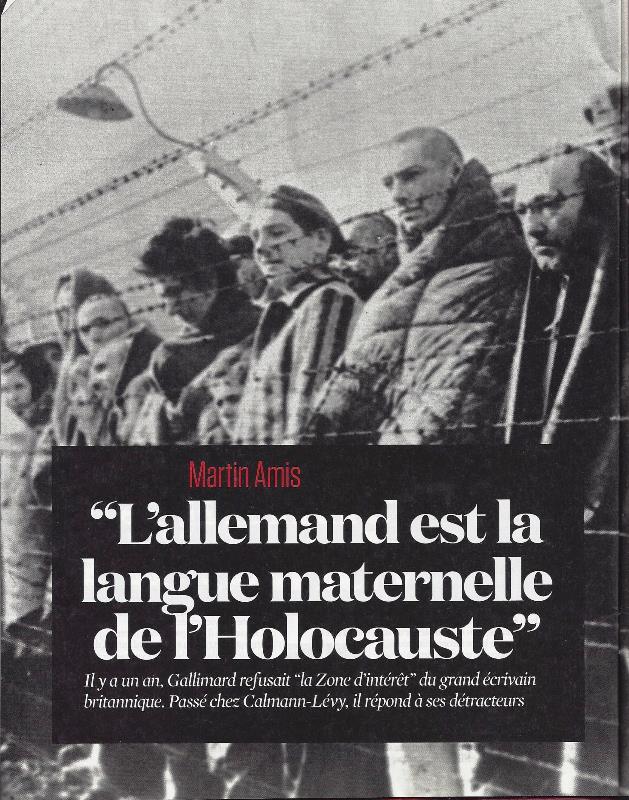

We can argue about the causes for these wars and the apportioning of blame, but the fact is that war begins, and ends, over here, with the support of citizens for the war machine, with the arrival of frightened refugees fleeing wars we have instigated. Telling these kinds of stories, or learning to read, see and hear family stories as war stories, is an important way to treat the disorder of our military-industrial complex. For rather than being disturbed by the idea that war is hell, this complex thrives on it. Viet Thanh Nguyen: Our Vietnam War never ended Trước mắt, Tin Văn sẽ đi bài tiểu luận của VTN, cùng trả lời phỏng vấn, cùng 1 bài điểm ở cuối sách, trong khi đọc nó. GCC có cảm tưởng nguồn của nó là Tên Điệp Viên của Conrad. Nhưng đọc câu đề từ của Nietzsche, thì lại nghĩ tới Ông Thánh Lò Thiêu, Jean Améry: Let us not become gloomy as soon as we hear the word "torture": in this particular case there is plenty to offset and mitigate that word-even something to laugh at. - Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals Torture, writes Améry, has "an indelible character". Whoever was

tortured, stays tortured. Rằng, kẻ tra tấn, là cứ thèm tra tấn suốt đời! Auschwitz Tháng Tư 1942 Obs 20 & 26 Aout 2015 Tiếng Đức là tiếng mẹ đẻ của Lò Thiêu Hãy nhớ rõ 1 điều, tiếng Đức không ngây thơ vô tội trước Lò Thiêu G. Steiner: Phép Lạ Hổng Martin Amis : "L’allemand est la langue maternelle de l’Holocauste" http://bibliobs.nouvelobs.com/romans/20150818.OBS4359/martin-amis-l-allemand-est-la-langue-maternelle-de-l-holocauste.html Tại

làm sao mà ông đặt tít cho cuốn sách của mình, là Miền Nhận Hàng

[la Zone d’intérêt: Miền Nam nhận họ, Miền Bắc nhận hàng]?

[Note: Câu này, bản in trên báo có tí khác, bản trên net] Tôi tính gọi nó là “Tuyết màu hạt dẻ”, nhưng Simenon đã chơi cái tít “Tuyết dơ” rồi. Nabokov phán, có hai thứ tít. Thứ lòi ra sau khi viết xong, như người ta đặt tên cho đứa bé, khi nó ra đời. Thứ kia mới khủng, nó có từ trước, ngay từ đầu, nó cắm mẹ vô não của bạn từ hổi nào hồi nào. Đây là trường hợp cuốn của tôi. Vùng nhận hàng, hay, Miền Lợi Tức, là công thức mà Nazi sử dụng để chỉ Miền Lò Thiêu. Một cái tít rõ ràng ngửi ra tiền. Ui chao, thảo nào Bắc Kít gọi, Đàng Trong: Nhà của chúng. Đàng Ngoài, là, tính nhượng cho Tẫu, để trả ơn, nhờ chúng mà làm thịt được thằng em ruột Nam Bộ, cùng lúc đánh thắng được cả hai thằng đế quốc thực dân, cũ và mới. Amis quả đúng là 1 nhà văn xì căng đan. Cuốn sách mới xb của ông, bị Gallimard vứt vô thùng rác, dù đây là nhà xb bạn quí của ông. Cũng đếch thèm nói năng, phôn, phiếc gì hết. Rồi 1 nhà xb Đức cũng chê. Sau cùng, nhà Calmann-Lévy in nó. Theo tin hành lang, Gallimard chê, vì không tới tầm. Nhưng cuốn này, quả là khủng. Gấu mê nhất cuốn Nhà Hội của ông. Có gần đủ sách của ông, nhưng thú thực, không chịu nổi! « La Zone d’intérêt » est votre second roman consacré à l’Holocauste. Est-ce que d’écrire sur le sujet impose une discipline particulière? J’aimerais vous dire que c’est pénible d’écrire sur le sujet, mais ce n’est pas le cas. C’est vrai que c’est la deuxième fois que je m’y intéresse, de manière assez incongrue peut-être. Ma femme est à moitié juive, ma belle-mère a eu des membres de sa famille qui sont morts pendant l’Holocauste. Mes filles sont liées à cette tragédie. Ça rajoute sans doute une dimension personnelle. J’aimerais écrire un troisième roman sur cette période avant de mourir. Ça terminerait la trilogie. Vous mariez, dans le livre, le sexe à l’extermination. Est-ce une manière de provoquer encore? Je n’y ai pas pensé pendant que je l’écrivais. Je voulais tenter d’aller au cœur du crime. Miền Nhận Hàng, Đàng Trong, Kẻ Phản Thùng.... Lần thứ nhì ông tấn công vô Lò Thiêu. Hẳn là căng lắm? Không, phải thêm cú nữa, mới thành 1 bộ ba cuốn, la trilogie Tôi muốn đi tới Trái Tim Của Bóng Đen: Hà Lội! Chúng

ta tụ tập nơi đây, trong phòng ốc sáng trưng, quyến rũ

như thế này, để bàn về số phận nhà văn lưu vong, chúng ta hãy im

lặng một phút, để nghĩ tới một vài người không có mặt ở phòng này.

Hãy tưởng tượng, thí dụ, những người di dân Thổ nhĩ kỳ đang lang

thang trong những con phố ở Tây Đức; thật xa lạ nhưng cũng thật thèm

muốn đối với họ, là thực tại chung quanh. Hay hãy tưởng tượng những thuyền

nhân Việt Và có lẽ chính là lý do này, mà, ‘tôi chọn con đường lưu vong’ hoá ra là chọn con đường về nhà, bởi vì nhà văn lưu vong trên đường đi tìm lưu vong như thế, lại trở nên gần gụi với cái ghế ngồi viết văn của mình, và với những lý tưởng mà chính chúng đã gợi hứng cho anh ta viết. Tuy nhiên, nếu phải tìm cho ra một dạng nào đó, a genre, cho cuộc sống của nhà văn lưu vong, thì có lẽ phải nói, nó thì bi hài, tragicomedy. Do những nhập thân có trước đó, [do cũng đã có tí ti hiểu biết về cái nơi sắp tới], anh ta có thể dễ dàng chấp nhận, thưởng thức, appreciating, những tiện nghi về mặt xã hội, về mặt vật chất của 1 chế độ dân chủ, chẳng thua, và khi còn hơn cả dân bản xứ. Nhưng, chính vì lý do này, [mà 1 trong những phó sản phẩm của nó, là rào cản về ngôn ngữ], anh ta nhận ra, anh ta chẳng là cái chó gì, chẳng đóng 1 vai trò nào có ý nghĩa, thấy mình thậm vô ích, trong cái xã hội mới đó. [Viết cứ như viết vào hư vô, đúng như nhà văn NMG đã từng than, là vậy!]. Cái xã hội dân chủ cung cấp cho nhà văn lưu vong một sự an toàn về mặt vật chất, đồng thời tước mẹ của anh ta cái lý do hiện hữu, như là 1 nhà văn, nghĩa là, làm cho anh ta trở nên vô tích sự, chẳng có ý nghĩa chó gì, về mặt xã hội. [Viết cứ như là thủ dâm, là… gì gì như Thầy Cuốc phán, Gấu quên mẹ nó mất, và được nhà văn Võ Đình gật gù khen, khiếp, chắc là vì thế này chăng?] Và vì cái sự mất mẹ nó ý nghĩa sống ở trên đời, mà, nhà văn hay không nhà văn, đếch ai chịu nổi. Brodsky The Condition We Call Exile,

As we gather here, in this

attractive and well-lit room, on this cold December evening, to discuss

the plight of the writer in exile, let us pause for a minute and think

of some of those who, quite naturally, didn't make it to this room.

or Acorns Aweigh Let us imagine, for instance, Turkish Gastarbeiters prowling the streets of West Germany, uncomprehending or envious of the surrounding reality. Or let us imagine Vietnamese boat people bobbing on high seas or already settled somewhere in the Australian outback. Let us imagine Mexican wet backs crawling the ravines of Southern California, past the border patrols into the territory of the United States. Or let us imagine shiploads of Pakistanis disembarking somewhere in Kuwait or Saudi Arabia, hungry for menial jobs the oil-rich locals won't do. Let us imagine multitudes of Ethiopians trekking some desert on foot into Somalia (or is it the other way around?), escaping the famine. Well, we may stop here, because that minute of imagining has already passed, although a lot could be added to this list. Nobody has ever counted these people and nobody, including the UN relief organizations, ever will: coming in millions, they elude com

Joseph Brodsky: Đi để đừng bao giờ trở về. I don't

know anymore what earth will nurse my carcass. Tôi

không còn biết nữa, mảnh đất nào sẽ bú mớm cho cái thân xác

này. … Nếu có gì tốt về lưu vong, thì đó là, nó dậy

cho một con người sự khiêm tốn. Và một con người như thế, có thể

dấn thêm một bước nữa, và giả dụ, rằng, bài học tối hậu của lưu vong,

là bài học về đạo hạnh. Và bài học này thì vô giá, nhất là đối

với một nhà văn, bởi vì, nó đem đến cho nhà văn một viễn tượng dài rộng

nhất có thể có được [the longest possible perpective]. “And thou art

far in humanity”, như Keats nói. (1). Bị mất tăm mất tích trong nhân

loại, trong đám đông, – đám đông ư? ở giữa hàng triệu triệu con người:

trở thành cây kim trong đống cỏ, như cách ngôn đã từng nói – nhưng

là cây kim mà mọi người tìm kiếm – đó là điều mà lưu vong là. (1)

Câu này, gõ Google, nó ra như thế này: Dấy lên từ bụi vô thường, Ngày qua tháng lại tà dương kiếp người… Thơ TKKA

Kafka’s Only Enemy

Kafka's social life is striking for the fact that he was generally well received by all: by men and women, Germans and Czechs, Jews and Christians alike. Not only was Kafka popular among his colleagues and superiors, who had known him for a long time, he was also at ease with the tables of strangers he might join at a hotel or sanatorium, and he was well liked by the more distant acquaintances of his close friends. In his everyday life, Kafka was friendly, helpful, charming, a sensitive listener, but also discreet. His witty, self-ironizing observations prevented anyone from seeing him as a sexual or intellectual rival. Kafka kept his distance from any sort of public feuds, and we find no harsh words for him in the diaries or letters that his close contemporaries left behind. With one notable exception. "The longer I'm away from Kafka, the more I dislike him, with his slimy maliciousness." These words were written by the doctor and writer Ernst Weiss in a letter to his lover, the actress Rahel Sanzara. Weiss had been one of Kafka's few friends not from Max Brod's circle, and he competed with Brod in a certain sense. In Weiss's view, the only way that Kafka could conceivably solve all of the problems in his life was to extract himself from his many obligations and entanglements in Prague, and begin a new literary existence in Berlin. It is not entirely clear what led these two men to part ways, but it seems Weiss was angry that Kafka, who had long promised to write a review of his novel Der Kampf (The Struggle), ultimately declined. The novel was published in April 1916, at a time when Kafka was suffering from a long spell of unproductivity and felt himself incapable of even the slightest literary work, but Weiss saw that as an excuse. "We plan to have nothing more to do with one another until things begin to go better for me," Kafka wrote to Felice Bauer. "A very reasonable solution." In the years after the war, the two writers managed a half-hearted reconciliation, but this did not quell Weiss's latent animosity, which experienced a resurgence after Kafka's death. Thus Weiss assured Soma Morgenstern, an admirer of Kafka, that Kafka had behaved "like a scoundrel" toward him. And as late as the 1930S, Weiss was still portraying his one-time friend as socially autistic, as he did in the magazine Mass und Wert (Measure and Value), even while expressing admiration for his literary work.

Kẻ thù độc nhất của Kafka. Nhờ viết bài thổi cuốn sách mà cũng vờ, sao không thù? GCC có nhiều kẻ thù là vậy!

Writers who spied The unsurprising link between authorship and espionage Nhà văn cớm Cái link chẳng có gì là ngạc nhiên giữa viết văn và làm nghề gián điệp Về tên Xịa, Alden Pyle, nhân vật kể chuyện – anh ký giả già, ghiền Hồng Mao, Fowler - trong Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng nhận xét, tôi chưa từng biết 1 tên với nhiều thiện ý, về tất cả trouble, do anh ta gây ra. *

Greene chọn Norman Sherry, giáo

sư văn chương đại học Trinity San Antonio, Texas, là người viết tiểu

sử, là do mê ông này, khi viết về Joseph Conrad [Conrad’s Western World].

Nhất là sự kiện Norman Sherry, để viết về Conrad, đã thực hiện những

chuyến đi thực tế tới vùng Viễn Đông và đặc biệt là những khám phá của

Norman Sherry ở Tây Phi về Trái Tim Của Bóng Đen, của Conrad. Chính Greene

đã tìm cách tiếp cận Sherry, qua một nhà báo, William Igoe. Ông này nói

với Sherry, trong một bữa cùng ăn trưa, “Có một tay, đúng là một huyền

thoại của chính thời đại của anh ta, và tay này rất mê tác phẩm của bạn”.

Sau đó, hai người gặp gỡ, vào lúc đó, như Sherry sau này mới biết, Greene

đang bị gia đình và bạn bè đòi hỏi, phải kiếm cho ra một tay viết tiểu sử

về mình. Và trong khi ông đang tỏ ra thích thú bởi nụ cười rất ư là đặc

biệt, và cặp mắt xanh của Greene, bất thình lình, ông này nói: “Bạn khó

mà viết về tôi, như là bạn viết về Conrad. Bạn khó có thể viết về tôi,

bởi vì bạn không thể tới Sài Gòn." [Bối cảnh của cuốn Người Mỹ Trầm

Lặng là Sài Gòn thập niên 1950. Câu nói của Greene là vào năm 1974, tình

hình chiến sự và thái độ của nhà cầm quyền miền nam không cho phép Sherry

tới đây, như đã từng tới Phi Châu, khi viết về Conrad.] Khó khăn thứ nhì, Greene

đòi hỏi, Sherry, người viết tiểu sử của mình, phải "theo từng bước

chân của tôi". Thế là Sherry phải đi thực tế tới những nơi từng làm

bà đỡ cho những tác phẩm lớn của Greene, như Mexico, Liberia, Cuba, Việt

Nam, và cả lố những vùng chẳng hề thân thiện với đám mũi lõ. Trong khi

cố gắng hoàn thành lời hứa, đi theo những vết chân của tôi, ông đã

tới những vùng như Haiti, Argentina, Paraguay, Japan, Malaya, Sierra

Leone, và nhiều nơi khác nữa, và trong những chuyến đi thực tế như vậy,

đã bị mù sáu tháng, bị sốt rét tại Africa, và hoại thư, khiến ông mất

một khúc ruột tại Panama. Chính trong cái bầu khí xám

xịt đó, là Sài Gòn thập niên 1950, mà cuộc tình tay ba, trong Người

Mỹ Trầm Lặng, với ba đỉnh của nó, được mở ra: tính dễ bị mua chuộc,

mà cũng rất ư là thành thực, không mầu mè, của một cô Phượng [với giấc

mơ lấy chồng Mẽo, làm dâu Mẽo, hay tệ hại hơn, làm dâu Đài Loan, Đại Hàn…

như những cô Phượng hiện nay ở Việt Nam…], tính dãn ra, chẳng còn muốn

vướng vào những vấn đề của một xứ xở thuộc địa như Việt Nam, của anh mũi

lõ già nghiền thuốc phiện, là Fowler, và sự ngây thơ của một anh Mẽo trẻ

tuổi đẹp trai, thiện nguyện viên, hay cố vấn Pyle! Đúng là một tam giác

lý tưởng để dựng nên một cuốn tiểu thuyết lý tưởng! Nó làm cho Zadie

Smith [trên tờ Guardian] nhớ tới trò chơi “jack straw”, trong đó mỗi người

chơi, tới lượt mình, rút một cọng rơm mà không đượcđụng những cọng rơm còn

lại. Tài nghệ của tiểu thuyết gia ở đây, là làm sao cân bằng cả ba, bắt

từng nhân vật đối diện với chính mình, và với hai kẻ kia, trong tấn trò

đời, với tất cả những lên voi xuống chó, những hy vọng, những thất bại

- và nhất là, phải làm sao cho độc giả đừng trông mong có được một nhận

định, đánh giá sau cùng, khi gấp sách lại, [và thở phào, rằng, việc đọc

của ta như vậy là xong!]. Greene không thích những độc giả của ông có được

sự hài lòng, thoải mái, theo nghĩa này: “Khi chúng ta không chắc chắn,

như vậy là chúng ta vưỡn còn sống!”

“Tôi là một kẻ có niềm tin lớn

lao vào Lò Luyện Ngục”, Greene đã từng trả lời như vậy, trong một cuộc

phỏng vấn. “Lò Luyện Ngục, với tôi, là có ý nghĩa…. một khi bị ném vào

đó, con người có ấn tượng về sự du di, chuyển động. Tôi không thể nào tin

vào Thiên Đàng. Mọi người cứ ỳ ra, ở đó. Đâu còn có điều gì để mà làm

nữa!” Gừng càng già càng cay, càng

ngày, tính ngây thơ ngốc ngếch, mù tịt về thế giới của anh chàng cố

vấn Mẽo Pyle càng nổi lên cùng với cuốn truyện, kể từ khi được xuất bản,

đúng như Fowler cảnh cáo anh ta: “Tôi cầu mong Chúa làm cho

anh hiểu được những gì anh đang làm ở đây. Ôi, tôi hiểu rất rõ, những

nguyên nhân, những mục đích, những ý hướng tốt đẹp của anh. Chúng luôn luôn tốt… Tôi chỉ mong, đôi