|

Lưới

khuya,

hồn ốc lạc thiên đường

Happy Birthday to you, Mom.

13.4. 2009

Richie & Jennifer Tran

Un renouvellement de la

culture de masse

Wikipédia

ou la fin de

l’expertise ?

Le printemps de Milan Kundera

par Guy Scarpetta

Mùa Xuân của Kundera

là một bài điểm cuốn mới ra lò của Kundera, Một

cuộc gặp gỡ, trên tờ Thế giới ngoại

giao, số Tháng Tư, 2009. Tin Văn sẽ

có bài tóm tắt.

Thằng

Khờ được việc

Người và Việc:

Trần Phong Giao, người gác

cổng văn học, tạp chí Văn

Sunday, April 05, 2009

Du Tử Lê

Cái tít này, “người gác cổng”, theo Gấu, mô phỏng của một tay ở trong

nước. (1)

Văn học nào mà cần người gác

cổng?

Người và Việc?

Chẳng lẽ một bài tưởng niệm, bạn bè của nhà thơ, và nhân đó, cả một nền

văn học, mà nhét vô mục Chó Cán Xe như

thế này?

(1) Hoàng Hưng, Thơ

Việt Nam

đang chờ phiên đổi gác.

Note: V/v ẩn dụ 'ngưòi gác' này, Gấu nghi, mấy anh

thi sĩ

VC thuổng của ngoại quốc, nhưng họ dùng theo cái nghĩa, người gác đền

thiêng, viện chư thần, đỉnh thi sơn...

Đền thiêng thì cần có người gác, còn kiêm việc ông từ, ngày ngày lo

việc cúng bái, cầu nguyện...

Bài viết của bạn ta có vài sai sót. Phạm Thị Hoài viết thành Nguyễn Thị

Hoài. Nguyên Ngọc không phải là người khám phá ra bà này, cũng không

phải là tác giả cụm từ 'văn chương minh họa' [của Nguyễn Minh Châu].

Trịnh Công

Sơn vs Lịch Sử

TCS:

Kẻ Sĩ?

30.4.2009

Under Construction!

NMG vs Lưu

Vong

Quand

Robert parle de

Jonathan

Littell,

père et fils

Cha

& Con Littell.

Ông bố

thì bị ám ảnh bởi chủ

nghĩa toàn trị Stalin, ông con, Nazi.

Tên ông

con, Jonathan October

Littell., là để đời đời ghi nhớ Cách

Mạng Tháng 10!

Tác

phẩm mới nhất của ông bố:

Chim Báo Bão, kể cuộc đụng độ giữa nhà thơ Mandelstam và đao phủ Stalin.

Life vs

Death

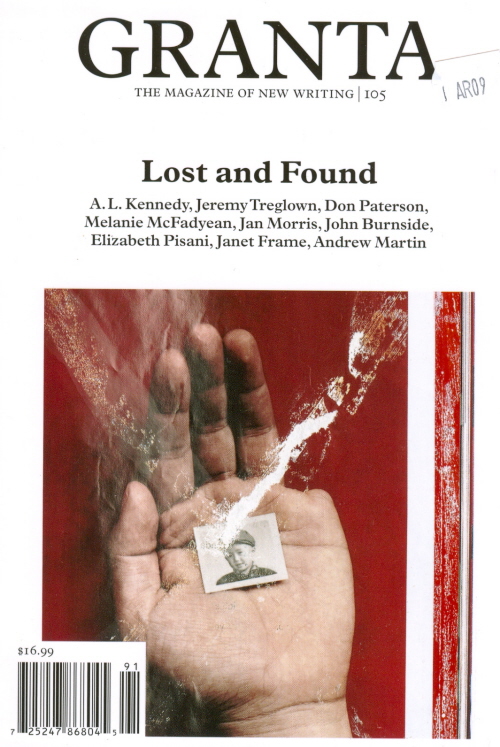

Cutting

Off Dissent:

Cắt ngón

tay li khai: Để phản đối biến cố Thiên An

Môn, 1989, nghệ sĩ Sheng Qi cắt ngón tay, tạo ra một số hình ảnh bàn

tay cụt ngón

tay của mình, trong có tấm hình ở nơi lòng bàn tay, là tấm hình một đứa

bé

trai.

Mất đi

và Kiếm lại được

*

EDITOR'S LETTER

ALEX CLARK

The vanishing point:

Điểm biến

When something is

lost, our

first instinct is often towards preservation: either of the thing

itself, its

memory and its traces in the world, or of the part of us that is

affected by

what is now missing. The pieces in this issue of Granta reflect on the

complex

business of salvage and try to bring into the light what we discover

when we

come face to face with loss.

It is rarely a

straightforward process.

JeremyTreglown's

thought provoking exploration of the gathering movement to exhume the

victims

of the Spanish Civil War amply demonstrates the tensions created when a

desire

to commemorate clashes with a desire to move forward, and when both

entirely

natural impulses are claimed by other agendas. Although his

investigation

illuminates the continuing aftermath of a particularly dark and

disastrous

episode in Spanish history, it has clear parallels with other

countries'

attempts to recover from traumatic events and forces us to question

whether an

apparently simple urge to remember and to pay tribute can remain

uninflected by

other equally complex concerns.

A similar ambiguity

informs

Maurice Walsh's dispatch from Ireland,

where he travelled to spend time with the Catholic priests whose

numbers have

been diminishing over the past few decades. He reports of a decline in

vocations that coincided with a widespread rise in secularism and an

attitude

towards the Church that hardened - perhaps irreversibly - after the

wave of

child-abuse scandals in the 1990s, which were seen not merely as

instances of

individual wrongdoing but as evidence of a collusion between a powerful

hierarchy and those whom it had sent into the community as trusted

individuals.

This shift in perspective has been well documented and, when the writer

and I

spoke about the piece in its earliest stages, we agreed that a fruitful

focus

would be what the priests themselves felt about this process of

marginalization.

Elsewhere, we feature some

extremely personal stories, perhaps none more so than Melanie

McFadyean's

'Missing', which relates the experiences, over nearly two decades, of

the Needham

family. Ben

Needham, a child of twenty-one months, disappeared on the Greek island of Kos in 1991; he has never been

found.

The moment of his disappearance - the moment when he was last seen by

members

of his family - resonates through her account with its utter

simplicity; a

child, playing in the sun, running in and out of doors, being

completely

childlike and completely unselfconscious. Then silence, and absence;

and then

the continuing lives of Ben's mother, Kerry, his grandparents, his

uncles and

the sister born after he disappeared. It is a familiar fictional

device, and

often characteristic of the stories we tell ourselves about defining

periods in

our lives, to suggest that everything can change in an instant. Much of

the

time, that is not really true, and rather more likely that a crisply

delineated

sequence of events allows us to cope with chaos and confusion. In the

case of

the Needhams, though, even that world-altering single moment, viewed

through

the prism of different people and the passage of time, can remain

painfully

resistant to closure.

There is a different kind of

examination of the past going on in Elizabeth Pisani's 'Chinese

Whispers', in

which the author recalls the night that she spent in Tiananmen Square

twenty

years ago, frantically attempting to phone in reports to her news

agency as

tanks (not to be confused with armored personnel carriers, as her

bosses on the

other end of the line curtly impressed on her) rolled in to crush the

ranks of

pro-democracy protestors filling the Square.

But Pisani's resurrection of

a night that, to her, an inexperienced reporter of twenty-four, was the

most

momentous she had ever lived through, proves rather harder to pin down

in the

retelling. Is her version of events correct to the last detail? Or has

she

embroidered and finessed her memories in the intervening years?

Sometimes, of course,

the

changing of the guard makes room for us to cast a lighter eye over

events, as

in Don Paterson's piece of memoir, which tells of his youthful passion

- and

passion is the right word - for evangelical Christianity, an effort to

exoticize his everyday life that led to fervent prayer sessions

enlivened by

the odd bout of angeloglossia. It seems that what he discovered as his

faith

faded was an unshakeable enthusiasm for rational thought. But he also

conjures,

as the best memoirs do, a portrait of another time - in this case, a

world of

weak tea, Jammie Dodgers and fearsome bullies. Equally evocative are

the pipe

smokers, captured in Andrew Martin's ode to a pleasure in peril, who

have found

themselves defending their commitment to a slower, temptingly detached

way of

life - their special brand of 'hypnotic latency', as Martin puts it.

In among these surveys of

vanishing worlds come three pieces of fiction: an artfully poignant

story by

Janet Frame, a wry tale of dentistry and disarray by A. L. Kennedy and

two

pieces of work by Altan Walker. Of Earthly Love, Walker's debut novel,

was

several years in the writing, rewriting and recasting and had yet to be

finished when the writer died in 2007. As I began to read the

manuscript,

knowing that it would never now be completed, I felt immediately that

if it

were to remain unseen readers would be deprived of a true delight; one

that

would introduce them to a wild, shifting, ungovernable voice, capable

of great

acts of ventriloquism and imagination. It is a real pleasure to be able

to

publish part of Walker's

manuscript here and to know that, in among the varieties of loss that

we are

often subject to, there remain treasures to find. _

NTS by NQL

Có lẽ

lần đầu tiên nó biết

thế nào là hạnh phúc.

NQL

Câu này, ‘độc’ hơn thịt vịt!

Chỉ những ai biết về NTS,

‘người đi qua đời tôi’, của biết bao nhiêu là em, thì mới thú câu này!

Tuyệt!

Cả băng này, Gấu đều quen, trừ

NQL, nhưng cái tay bảnh nhất, không phải là mấy tay hay được nhắc đến

như PXN,

NTS…

NQT

BVVC

The destruction of someone's

native land is as one with that person's destruction. Séparation

becomes

déchirure [a rendingl, and there can be no new homeland. "Home is the

land

of one's childhood and youth. Whoever has lost it remains lost himself,

even if

he has learned not to stumble about in the foreign country as if he

were

drunk." The ‘mal du pays’ to which Améry confesses, although he wants

no

more to do with that particular pays—in this connection he quotes a

dialect

maxim, "In a Wirthaus, aus dem ma aussigschmissn worn is, geht ma

nimmer

eini" ("When you've been thrown out of an inn you never go

back")—is, as Cioran commented, one of the most persistent symptoms of

our

yearning for security. "Toute nostalgie," he writes, "est un

dépassement du présent. Même sous la forme du regret, elle prend un

caractère

dynamique: on veut forcer le passé, agir rétroactivement, protester

contre

l'irréversible." To that extent, Améry's homesickness was of course in

line with a wish to revise history.

Sebald viết về Jean Améry:

Chống Bất Phản Hồi: Against The Irreversible.

[Sự huỷ

diệt quê nhà của ai

đó thì là một với sự huỷ diệt chính ai đó. Chia lìa là tan hoang, là

rách nát,

và chẳng thể nào có quê mới, nhà mới. 'Nhà là mảnh đất thời thơ ấu và

trai trẻ

của một con người. Bất cứ ai mất nó, là tiêu táng thòng, là ô hô ai

tai, chính

bất cứ ai đó.... ' Cái gọi là 'sầu nhớ xứ', Améry thú nhận, ông chẳng

muốn sầu

với cái xứ sở đặc biệt này - ông dùng một phương ngữ nói giùm: 'Khi bạn

bị

người ta đá đít ra khỏi quán, thì đừng có bao giờ vác cái mặt mo trở

lại' -

thì, như Cioran phán, là một trong những triệu chứng dai dẳng nhất của

chúng

ta, chỉ để mong có được sự yên tâm, không còn sợ nửa đêm có thằng cha

công an

gõ cửa lôi đi biệt tích. 'Tất cả mọi hoài nhớ', ông viết, 'là một sự

vượt thoát

cái hiện tại. Ngay cả dưới hình dạng của sự luyến tiếc, nó vẫn có cái

gì hung

hăng ở trong đó: người ta muốn thọi thật mạnh quá khứ, muốn hành động

theo kiểu

phản hồi, muốn chống cự lại sự bất phản hồi'. Tới mức độ đó, tâm trạng

nhớ nhà

của Améry, hiển nhiên, cùng một dòng với ước muốn xem xét lại lịch sử].

*

Nhà văn là một thứ phong vũ

biểu. Thứ dữ dằn, một loài chim báo bão.

"Gấu nhà văn", về nhà hai lần,

nhưng lần thứ ba, tính về, ngửi thấy có gì bất an, hay là do quá rét,

bèn đi một

cái mail, hỏi thăm thời tiết nơi quê nhà, và được trả lời, không được

đẹp, thế

là bèn đếch có dám mò về!

*

Khi thằng cu Gấu lên tầu há mồm

vô Nam, bỏ chạy quê hương Bắc Kít của nó, ngoài hai cái rương [cái hòm]

bằng gỗ

nhỏ, có thể để mỗi cái lên một bên vai, trong đựng mấy cuốn sách, thằng

bé còn thủ theo, toàn là

những

kỷ niệm về cái đói.

Và nửa thế kỷ sau trở về, cũng mang về đầy đủ những

kỷ niệm

đó, và trên đường về, tự hỏi, không hiểu bà chị mình có còn giữ được

chúng…

Bà giữ

đủ cả, chẳng thiếu một, nhưng, chị giữ một kiểu, em giữ một kiểu.

Nói rõ

hơn, cũng những kỷ niệm

về cái đói đó, ở nơi Gấu, được thời tiết Miền Nam làm cho dịu hết cả

đi, và đều

như những vết sẹo thân thương của một miền đất ở nơi Gấu.

Y như kỷ niệm sau đây,

lần đầu làm quen thành phố Sài Gòn.

*

1965. Những ngày cuộc chiến

tuy chưa dữ dội nhưng đã hứa hẹn những điều khủng khiếp. Người Mỹ đổ

quân xuống

bãi biển Đà Nẵng, liền sau đó là lần chết hụt của tôi tại nhà hàng Mỹ

Cảnh. Tất

cả những sự kiện đó, mỉa mai thay, chỉ làm cho bóng ma chiến tranh thêm

độc,

đẹp, thêm quyến rũ và trở thành những nét duyên dáng không thể thiếu

của cô bé.

Của Sài-gòn.

Chỉ có

những người vội vã rời

bỏ Sài-gòn ngay những ngày đầu, họ đã không kịp sửa soạn cho mình một

nỗi nhớ

Sài-gòn. Còn những ai ở trong tâm trạng sắp sửa ra đi, đều tập cho quen

dần với

cơn đau sẽ kéo dài. Đều lựa cho mình một góc đường, một gốc cây, một

mái nhà...

để cười hay để khóc một mình. Một mẩu đời, một đoạn nhạc, một bóng

chiều, một

giọt mưa, một sợi nắng... để gọi thầm trong những lúc quá cô đơn. Để

mai kia

mốt nọ, trên đường tha phương cầu thực, nơi đất khách quê người, những

khi ngọn

gió heo may bắt đầu thổi, những khi ngồi bó gối bên trời, nhìn lá vàng

rơi đầy,

lấy tay che thời gian không nổi, hay những đêm tàn nghe bếp lửa réo

gọi... sẽ

nhâm nhi những cọng cỏ tưởng tượng của quê hương. Ôi,"Ôm em trong tay

mà

đã nhớ em ngày sắp tới" (1). Hãy cho tôi thăm lại con phố Bonard, nơi

có

bót Hàng Ken (2), chú bé di cư ngày nào ngơ ngác, rụt rè làm quen, tự

mình khám

phá Sài-gòn. Gần gốc cây chỉ còn trong cậu bé ngày xưa, một người đàn

ông đánh

đập dã man một người đàn bà. Không quên bài học Công Dân, chú bé chạy

vào trong

bót. Chú bị ăn bạt tai, cùng những lời sỉ vả, người ta đánh vợ, mắc mớ

chi tới

mày. Đồ con nít Bắc kỳ di cư, vô đây làm tàng. Ôi bài học đầu tiên khi

tìm cách

làm quen thành phố, được thời gian gọt giũa trở thành một nốt ruồi son

đáng yêu

biết là chừng nào trên khuôn mặt cô bé. Trên khuôn mặt Sài-gòn.

Một thành phố mà tôi đã chết

ở trong,

nay sống lại,

chỉ để kể về nó.

Lần Cuối Sài Gòn

Kỷ

niệm, kỷ niệm

Simenon

trả lời tờ The Paris Review

|

|