|

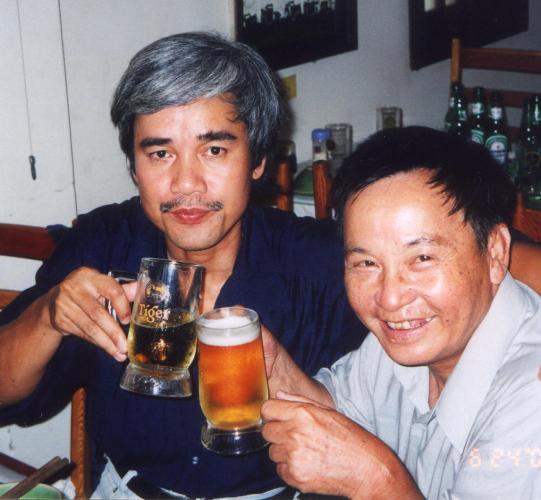

Gấu có những kỷ niệm khủng khiếp về cái đói, khi còn là 1 thằng bé nhà quê Bắc Kít. Có những kỷ niệm, là của ông bố của Gấu. Thí dụ cái chuyện bà nội của Gấu, chồng chết sớm, nuôi đàn con, có nồi thịt, bắt con ăn dè ăn xẻn thế nào không biết, nồi thịt biến thành nồi ròi. Vô Nam, phải đến sau 30 Tháng Tư, Gấu mới được tái ngộ với cái đói, những ngày đi tù VC.Thê lương nhất, và cũng tiếu lâm nhất, có lẽ là lần Gấu Cái đi thăm nuôi, lần đầu, sau mấy tháng mất tiêu mọi liên lạc với gia đình. Cái tật viết tí tí, không bao giờ dám viết ra hết, kỷ niệm, hồi nhớ, tình cảm… nhất là thứ kỷ niệm tuyệt vời, nhức nhối.... là do cái đói gây nên!  Vợ chồng con

cái nhà Gấu, liền sau 30 Tháng Tư 1975: Đói tàn khốc! Câu chuyện tiếu lâm về Bác, do

Gấu phịa, và kể cho mấy anh quản

giáo Đồ Hoà nghe, là vào thời gian Gấu vừa thoát “khổ nạn trong khổ

nạn”, ra

khỏi tổ trừng giới, được trả về đội, và được đi lao động, và do có tí

tiền gia

đình gửi cho, bèn mua chức Y tế Đội, tối tà tà đi từng lán, ghi tên

trại

viên khai bịnh, sáng hôm sau, sau khi chào cờ, đọc tên, dẫn qua khu

bệnh xá. Nhờ lần thăm nuôi đầu tiên, nhờ

tiền gia đình gửi cho, cuộc đời tù của

Gấu thay đổi

hẳn. Buổi tối, Gấu thường la cà mấy lán, dự tiệc trà, thường là do mấy

trại

viên ban ngày có gia đình thăm nuôi mời. Để đáp lại, Gấu bèn trổ nghề

kể chuyện

tiếu lâm, quay phim chưởng. Danh tiếng vượt khỏi đội, tới mấy đội khác,

rồi tới

tai mấy ảnh. Và được mấy ảnh mời, cho ngồi nhậu chung, kể chuyện tiếu

lâm. So với câu chuyện về Bác, của NQL, cùng một một dòng, "hậu quả của hậu quả”, nhưng chuyện của Gấu, thì quá thường, so với của NQL. Nay xin kể ra đây, cho rảnh nợ! Trước

khi kể Gấu cũng rào đón với mấy Quan quản giáo, đúng hơn, mấy Đấng

TNXP, đừng có bắt tội thằng kể, và được OK. Theo như truyền kỳ, thuở đó, thuở đó, Miền Bắc có một đội banh vô địch, đánh đâu thắng đó, và lần đó, qua Âu Châu dự World Cup, mang được Cup về cho xứ Mít. Trong bữa tiệc chia tay, ông bầu, bị đám báo chí Tây Phương phục rượu, xỉn quá, bèn phụt ra bí quyết: -Mỗi khi ra trận, tui kêu cả đám cầu thủ tới, dặn một câu... thế là tụi nó đá như điên. -Câu gì mà ghê thế ? Thư tín 1 NQL tả chân quá siêu. Liên minh

các chế độ hà khắc tạo ra những

con người ẩn ức, để mặc bản năng hướng dẫn, đọc thấy thương, không thấy

tục. "Nhà

phê bình cần tri thức và bản lĩnh. Tôi thấy mình có cả hai." Phạm Xuân

Nguyên đã nói một câu rất ngạo như thế. Bảnh thật.

Phán như thế mới là phán, và chẳng cần “điều tiết” làm khỉ gì nữa. NQT

Hai

bài viết

của NDB, về Ngọc Giao, và về Trịnh Cung [trong vụ ‘tham vọng chính trị

của TCS’],

đều có vấn đề. Từ từ, Gấu sẽ giải thích

sau, và sẽ minh họa, bằng chính những kỷ niệm

mà Gấu

đã kinh qua, thí dụ như cái vụ mân mê “bảo vật Nga” tuyệt vời!

!

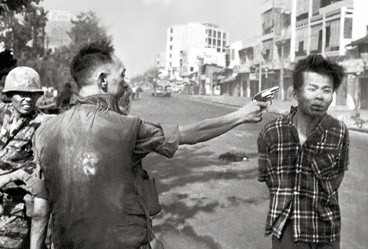

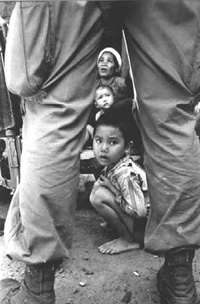

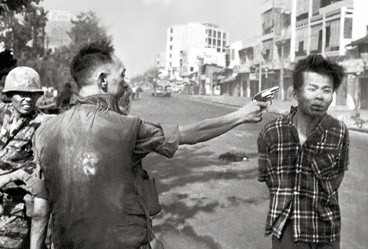

Vietcong Execution, The photo of the execution at

the hands of Vietnam's police chief,

Lt. Colonel Nguyen Ngoc Loan, at noon on Feb. 1, 1968 has reached

beyond the

history of the Indochina War - it stands today for the brutality of our

last

century. October 2004 Minh bạch lịch

sử. Qua câu phán

của Faas, trưởng phòng hình ảnh AP, Sài Gòn, trước 1975: Hay, câu của

Adams, tác giả bức hình:  Quản giáo,

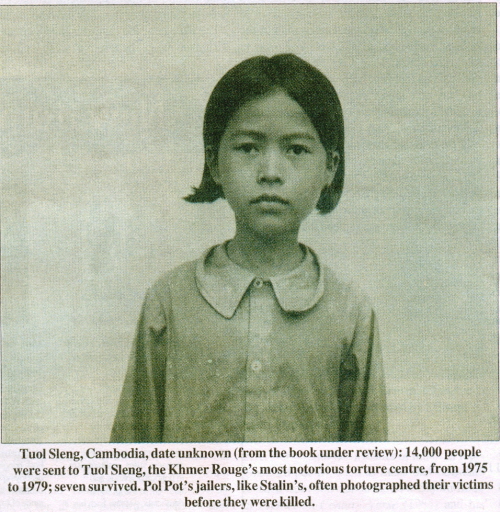

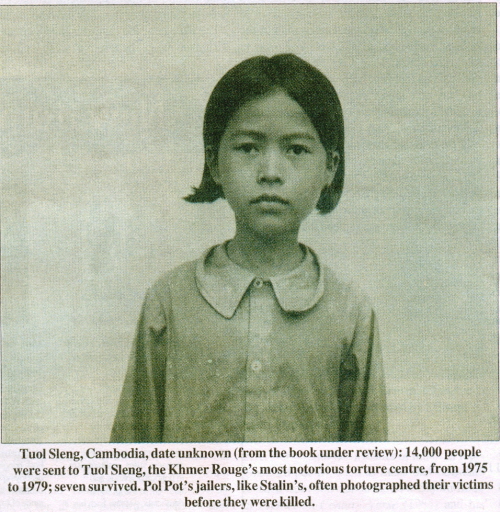

cai tù Pol Pot, giống như của Stalin, có cái thú trước khi làm thịt ai

thì cho

chụp hình làm kỷ niệm "Who

are you who will read these words and study these photographs, and

through what

cause, by what chance, and for what purpose, and by what right do you

qualify

to, and what will you do about it?" Tỏa Sáng Ðộc Ác

Anh

là thằng chó nào, kẻ sẽ đọc những từ này, nghiên cứu những bức hình

này, và qua

lý do gì, bởi cơ may nào, và vì mục đích chi chi, và bằng cái quyền chó

nào mà

anh cho phép xứng đáng, đủ tiêu chuẩn để làm những chuyện như trên?  Bị chiếu tướng Note: Bài viết

này, về "bị chụp hình", tuyệt! There is something predatory about all photography. The portrait is the portraitist's food. In a real-life incident I fictionalized in Midnight's Children, my grandmother once brained an acquaintance with his own camera for daring to point it at her, because she believed that if he could capture some part of her essence in his box, then she would necessarily be deprived of it. What the photographer gained, the subject lost; cameras, like fear, ate the soul. Có cái gì tựa

như là “ăn sống con mồi”, nếu nói về chụp hình. Bức hình là thức ăn của

nhiếp ảnh

gia [hãy nhớ câu của Eddie Adams, trên]. Ui chao, nhìn

cái hình vợ chồng con cái Gấu, thì mới ngộ ra chân lý: VC ăn, thịt

sống, còn

anh thợ chụp hình ăn, linh hồn!

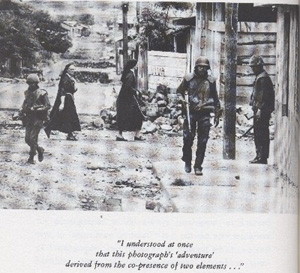

Bạn nhìn bức

hình trên, đọc chú thích của Roland Barthes [Tôi hiểu liền lập tức,

'cuộc phiêu

lưu' của tấm hình - của Koen Wessing, Nicagagua, 1979, trích từ cuốn

Roland

Barthes: Camera Lucida: Suy tưởng về chụp hình, Reflections on

Photography, bản

tiếng Anh của Richard Howard - là do sự đồng-hiện diện của hai phần

tử], và so

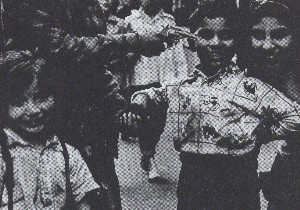

sánh với bức của Henri Huet.   Tôi đếch thèm để ý đến khẩu súng, mà là, hàm răng sún của chú bé! WILLIAM KLEIN: LITTLE Nguồn Mẩu trên, với

hình ảnh kèm, từ 1 trang TV cũ, được GNV sử dụng ở đây, để giới thiệu

một bài

viết thật tuyệt vời về hình ảnh, trên tờ TLS số 11 Tháng Ba, 2011: Hình Ảnh. Những Kẻ Ðem Tin Xấu. Alex

Danchev đọc cuốn The Cruel Radiance

[Tỏa Sáng Ðộc Ác]. Hình ảnh và bạo lực chính trị. Bài viết nhắc

đến những nguồn trứ danh về hình ảnh, từ “hào quang” của Walter

Benjamin, tới

Susan Sontag, nhưng… quên Roland Barthes và cuốn trứ danh của ông! Ðọc caption

tấm hình dưới đây, G bất giác nhớ đến

tướng

NNL, và bức hình trứ danh của ông, mà theo như Gấu - khi đó làm

Radiophoto-operator

cho UPI, là 1 trong những người đầu tiên được nhìn nó, trên máy chuyển

hình của

AP đặt ngay kế bên máy của UPI - được biết, ông tướng đã cho vời ký giả

ngoại

quốc tới, để chứng kiến ông xử tên tên VC.   Quản giáo, cai tù Pol Pot, giống như của Stalin, có cái thú trước khi làm thịt ai thì cho chụp hình làm kỷ niệm  PHOTOGRAPHY Susie

Linfield THE CRUEL

RADIANCE Photography

and political violence 325pp. University

of Chicago Press. $30; distributed in the UK by Wiley. £19.50.

9780226482507 Susie

Linfield takes as her title, and her text, a passage from James Agee.

In the

remarkable work of lyric reportage that he fashioned to accompany

Walker

Evans's equally remarkable photographs of the poor sharecroppers of

Alabama in

the Great Depression, Let Us Now Praise

Famous Men (1941), Agee wrote: For in the

immediate world, everything is to be discerned, for him who can discern

it, and

centrally and simply, without either dissection into science or

digression into

art, but with the whole of consciousness, seeking to perceive it as it

stands:

so that the aspect of a street in sunlight can roar in the heart of

itself as a

symphony, perhaps as no symphony can: and all of consciousness is

shifted from

the imagined, the remissive, to the effort to perceive simply the cruel

radiance of what is. For Agee,

the crucial agent of influence here is the camera. He continued: "This

is

why the camera seems to me, next to unassisted weaponless

consciousness, the

central instrument of our time". Linfield

takes up where Agee left off. It is the camera, she argues, that has

done so

much to globalize our consciences; the camera that has brought us the

twentieth

century's bad news. Her work is at heart a serial reflection on our

visual

encounter with human suffering: the suffering of strangers. It speaks

to our

response, and our responsibility - "the opportunity, and the ability,

to

be moved by the plight of others". She adopts the question framed by

the

philosopher Richard Rorty, "Why should I care about ... a person whose

habits I find disgusting?" and his suggested answer: "Because her

mother would grieve for her". Linfield's contention is that the

photograph

is a tutorial in the grievous and the grievable. "The camera has been a

key tool - perhaps the key tool - in enabling such empathic leaps." The

Cruel Radiance is a treatise on moral witness and empathic leaps: a

book of

brief lives - grief lives - on both sides of the camera. Put

differently, it is a book about the ethical freight of that little

sliver of

sentience, the photograph, sparingly but discriminatingly illustrated.

Inescapably, it is also about the bearer of the bad news, the

photographer.

Linfield examines three of the masters: "the optimist", Robert Capa;

"the catastrophist", James Nachtwey; and "the sceptic",

Gilles Peress. Each in his own way is exemplary, as their sobriquets

serve to

indicate, and her treatment of them is exemplary, too, for its

impassioned

clarity. John Berger is lauded in this work as "the most morally cogent

and emotionally perceptive critic that photography has produced". For

Linfield,

criticism is a high calling. If these attributes are the test, she is

equal to

it. There is a scrupulous attentiveness to her looking-in and

arguing-out. The case

study of Capa is a thoroughgoing revaluation. For Linfield, Capa was

something

more than the wild rover, if-your-pictures-aren’t-good-enough-you'

re-not-close-enough

debonair existentialist of the combat zone. For the world's greatest

war

photographer, he was surprisingly uninterested in carnage, or for that

matter

in battle. What drove him was not atrocity but possibility - "the lived

knowledge of political possibility". His interest was, fundamentally,

the

moralist's. Capa was a moralizer, one might say, as opposed to a

demoralizer.

"His photographs record the twentieth century's moments of militant

humanism", resumes Linfield in a moving peroration: and they do this by

how he, working at the time, made them and by what we, in the present,

bring to

them. His images are antifascist because they document a flawed, deeply

scarred

humanity, and because they honor rather than scorn those flaws and

those scars.

Capa's photographs show us that human beings suffer, and make us want

to know

why; they show us that human beings endure, and make us want to know

how. They

show us that striving for a more-just world can sometimes succeed but

more

often fails, yet that to do so is never absurd or inconsequential. The case

study of Capa's successor, James Nachtwey, is the best thing yet

written on

that remorseless ascetic. As a bringer of bad news, Nachtwey is

unparalleled.

At the beginning of his signature collection, Inferno (1999), he quotes

Dante:

"Through me is the way to join the lost people". Linfield is a

disquieted admirer; she wrestles with her scruples and his detractors

(most

productively with the philosopher J. M. Bernstein). Nachtwey's

photographs are didactic .... [His] particularly potent blend of

graphic,

sometimes disgusting subject matter and

bold, imposing compositions make it hard to maintain, or even

establish, a free

rein of emotions, much less of ideas. His images are overwhelming; they

can

make the viewer feel very small. (I sometimes think of Nachtwey as the

Richard

Serra of photography.) His photographs' great value - their utterly

uncompromising depiction of physical suffering - is also their

limitation.

Nachtwey's images are astonishing, but they are also inflexible. In the end

she concludes that it is necessary work. "Nachtwey's photographs are an

odd, compelling combination of misery and serenity, of edginess and

supreme

control, of horrible content and stylized form: they are, in short,

visual oxymorons.

But the perfection of their compositions - their so-called beauty -

should not

deflect us: Nachtwey's photographs are brutal, and they show us more

than we

can bear. But not more than we need to see." As if to underline her

argument, the examples chosen as illustrations of his work are not to

be seen

in this book. What appears instead is a grey box, with a bare legend:

"James Nachtwey Studio denied permission to reproduce this photograph.

It

can be found in James Nachtwey, Inferno,

p.174". Revealed and concealed, the starving man of the Sudan and the

hanging man of Afghanistan continue to perturb. If photographs teach us

about

our failure to comprehend the human, as Linfield believes, James

Nachtwey's

photographs help us to come closer: to fail better. The pages on

Nachtwey's contemporary Gilles Peress are no less searching. "For

Peress", Linfield observes, "photography 's a way to think about the

world." He is a philosopher with a camera. He is also a democrat, and a

humanitarian. Photographs are open documents, he has said, "where half

of

the text is in the reader", a proposition brilliantly illustrated

by an off-centre, out-of-kilter group portrait of the victims of the

Shah of

Iran's secret police, bearing the scars (and the prostheses) of their

torture;

and an oddly tender still life of bare feet, shoes and socks, left for

dead in

a Kosovan field. Peress contends that every image has four authors: the

photographer, the camera, the viewer, and reality. In Linfield's words,

his genius

has been ... to incorporate a critique of photography's objectivity

into that

obstinate bit of bourgeois folklore formerly known as truth. He

embraces

postmodern skepticism, but uses it to enlarge photographic

possibilities rather

than to discredit the medium. Peress has taken the alienated

sensibility

typical of, and prized by, modem photographers and fused it to a

passionate

engagement with the world outside himself. It is not

too much to suggest that Linfield herself wishes to do something

similar. Her

book is at once a meditation on the democratic possibilities of the

medium and

an intervention in the somewhat impoverished critical discourse about

it. Not

for nothing is the opening chapter entitled "A Little History of

Photography Criticism; or, Why Do Photography Critics Hate

Photography?".

The first part of this title summons the ghost of Walter Benjamin, and

his

"Little History of Photography" (1931); the second targets one critic

in particular, together with her epigones, "the post modems". If John

Berger is the benchmark, Susan Sontag is the bête noire. By her own

admission,

Linfield is writing against Sontag, against coolness, against

detachment,

against condescension - against the critical tone set by On Photography

(1977).

Linfield pits Pauline Kael on the movies against Sontag on photography

and

finds Sontag wanting. (Impossible to imagine a Sontag collection called

Kiss

Kiss Bang Bang.) The tone, and the reservation, are neatly encapsulated

in

Sontag's last utterance on the subject, "Photography: A little summa"

(2003). "A photograph may be telling us: this too exists. And that. And that. (And it

is all 'human'.) But what are we to do

with this knowledge - if indeed it is knowledge, about, say, the self,

about

abnormality, about ostracized or clandestine worlds?" The Cruel

Radiance

is an attempt to answer that question. As criticism, it is a work of

deep

distinction. It will surely become part of the history of its field; in

its own

comer, Sontag's Regarding the Pain of Others (2003) suffers by

comparison. As

treatise, it is not quite an integral whole. Betraying its origins, it

remains

a series of essays, or investigations. (Why is the literature of

photography so

essayistic? Does the sliver insist on the short form?) There are

lacunae.

"Perhaps the camera promises a festive cruelty", Judith Butler has

suggested, of the images of Abu Ghraib; she writes provokingly of "the

moral indifference of the photograph, coupled with its investment in

the

continuation and reiteration of the scene as a visual icon". Thus are

Sontag's theories dealt with. Butler's are still current. Linfield

joins a

select company. In the

preamble to Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, James Agee posed a series of

unforgettable questions to his readers. Susie Linfield bids to do the

same.

"Who are you who will read these words and study these photographs, and

through what cause, by what chance, and for what purpose, and by what

right do

you qualify to, and what will you do about it?" In the preamble to Let

Us

Now Praise Famous Men, James Agee posed a series of

unforgettable

questions to

his readers. Susie Linfield bids to do the same. "Who are you who will

read these words and study these photographs, and through what cause,

by what

chance, and for what purpose, and by what right do you qualify to, and

what

will you do about it?"

|