|

|

On Being

Photographed Outside a

photographic studio in South London, the famous Avedon backdrop of

bright white

paper awaits, looking oddly like an absence: a blank space in the

world. In

Avedon's portrait gallery, his subjects are asked to occupy, and

define, a

void. Somebody once told me that a frog on a lily pad keeps its eyes

(which see

by relative motion) so still that they see nothing at all, until an

insect

flies across their field of vision and becomes literally the only thing

there,

captured without escape on the white canvas of the frog's artificial,

temporary

blindness. Then snap, and it's gone. There is

something predatory about all photography. The portrait is the

portraitist's

food. In a real-life incident I fictionalized in Midnight's Children,

my

grandmother once brained an acquaintance with his own camera for daring

to

point it at her, because she believed that if he could capture some

part of her

essence in his box, then she would necessarily be deprived of it. What

the

photographer gained, the subject lost; cameras, like fear, ate the

soul. If you

believe the language-and the language itself never lies, though liars

often

have the sweetest tongues-then the camera is a weapon: a photograph is

a shot,

and a session is a shoot, and a portrait may therefore be the trophy

the hunter

brings home from his shikar. A stuffed head for his wall. It may be

gathered from the above that I do not much enjoy having my picture

taken, do

not enjoy becoming, rather than exploring, a subject. These days

writers are

endlessly photographed, but for the most part these aren't true

portraits-they

are publicity pix, and every newspaper, every magazine, must have its

own.

Mostly the photographers who work with writers are kind. They make us

look our

best, which isn't always easy. They compliment us on being interesting.

They

ask our opinions. They may even read our books. Richard

Avedon is the author of some of the most striking portrait photographs

of our

day, but he is not, in the sense I have used the term, kind. He looks

like an

American eagle, and he sees his subjects, against white, with a bleak

unblinking eye, whether they are writers or the mighty of the earth or

anonymous folks or his own dying father. Perhaps, for Avedon, the

stripped-down,

head-on technique of his portraiture is a necessary alternative to the

high-gloss fantasy world of his other life as a fashion photographer.

In these

portraits he is not selling but telling. And perhaps he is excited,

too, by the

fact that the people he is looking at are not members of that new tribe

created

by the camera: the tribe of professional subjects. If the

camera is a stealer of souls, is there not something Faustian about the

contract between photographer and model, between the Mephistophilis of

the

camera and the beautiful young men and women who come to life, hoping

for

eternity (or at least celebrity), before its one-eyed stare? Models

know how to

look, the good ones know what the camera sees. They are performers of

the

surface, manipulators and presenters of their own extraordinary

outsides. But

finally the model's look is an artificiality, it is a look about how to

look.

Off-duty models photograph one another ceaselessly, defining each

passing moment

of their lives-a lunch, a stroll, a meeting-by committing it to film.

Garry

Winogrand, quoted in Susan Sontag's On

Photography, says that he takes photographs "to find out what

something will look like photographed," and these professional subjects

are similarly trapped - they can never step outside the frame. They

become

quotations of themselves. Until the camera loses interest, and they

fade away.

The story of Faust does not have a happy ending. Avedon's

glamour photography has often touched on the theme of beauty and its

passing.

In a recent sequence the supermodel Nadja Auermann is seen in a series

of

surreal high-fashion clinches with an animated skeleton who is, of

course, a

photographer. Death and the maiden, a spectacular, with costumes by the

great

designers of the world. Perhaps Avedon is making a joke at his own

expense, the

skeleton as grand old man; perhaps he is hinting at the passing of the

supermodel

phenomenon. Equally relevant, however, is his wholehearted willingness

to enter

into the high-budget, high-gloss elaboration of this type of

mega-commercial

rag trade extravaganza. This is no ivory tower artist. The contrast

with his portraiture could not be greater. The portrait photograph is

Avedon's

naked stage, his blasted heath. Is it, I wonder, that one has to do something to exceptional beauties-cover

their faces in icicles, make them dance with skeletons-to make them

interesting

to photograph; whereas unbeauties, the faces of real life, are

rewarding even

(only) when unadorned? A great

portrait photograph is about insides. Cartier-Bresson and Elliott

Erwitt catch

their people on the wing, as it were: often, their work is revealing

because

the subjects have been caught off guard. Avedon is more formal: the

white

sheet, the majestic old plate camera on its tripod. In this setup it is

the

insect that must be perfectly still, not the frog. I have seen

a lot of photographers work. I remember Barry Lategan in a natty beret

snapping

away during an interview, nodding every time I said something he liked.

I began

to watch him carefully, becoming dependent on his nods, growing

addicted to his

approval: performing for him. I remember Sally Soames persuading me to

stretch

out on a sofa and more or less lying on top of me to get the shot she

wanted, a

shot in which, unsurprisingly, I have a rather dreamy expression in my

eyes. I

remember Lord Snowdon rearranging all the furniture in my house,

gathering bits

of "Indianness" around me: a picture, a hookah. The resulting picture

is one I have never cared for: the writer as exotic. Sometimes

photographers

come to you with a picture already in their heads, and then you're done

for. I have seen

a lot of photographers work, but I never saw anyone take as few

pictures in a

session as Avedon does with his big plate camera. Is it that he knows

exactly

what he wants, or that he is content to take what he gets, I wondered:

for Mr.

Avedon is a man on a tight schedule. Some people will give him more

than

others-so does the onus of becoming a good photograph rest with us, his

non-professional subjects, who know rather more about our insides than

our

outsides? Must we reveal ourselves, or will his sorcery unveil us

anyhow? He positions

me just as he wants me. I am not to sway, even by a millimeter, as I

may go out

of focus: it's that critical. I must hold my expression for what seems

an

eternity. I find myself thinking: this is how I look when I am being

made to

look like this. This will be a photograph of a man doing something

awkward to

which he is not accustomed. Then, shrugging inwardly, I surrender to

the great

man. This is Richard Avedon, I tell myself. Just let him take the damn

picture

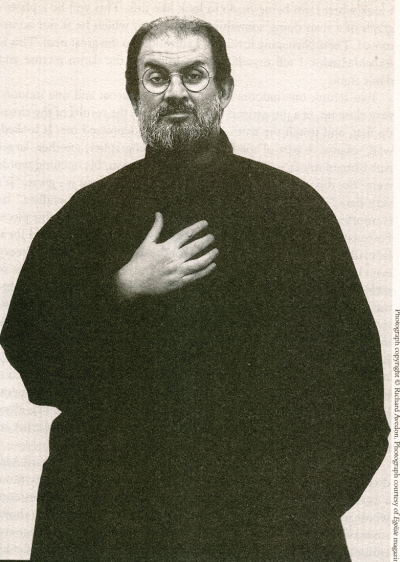

and don't argue. Two setups,

one indoors in a long black raincoat and one indoors, very close up, in

a

pin-striped black shirt. I saw the results of the close-up first, and

to tell

the truth it shocked and depressed me. It looked, well, satanic. A part

of me

blamed the photographer; another, larger part blamed my face. The next

time I

met Avedon, his opening words were "So, did you hate it?" I was

unable to grin and say, it's great. "It's very dark," I said.

"Oh, but the other picture's much friendlier," he comforted me. The

other picture is the one accompanying this piece. Fortunately, I really

like

it. I'm not sure if "friendly" is the word for it (actually, I am

sure, and "friendly" is not

the word for it; I have a cheery, even chirpy way of looking at times,

and this

is definitely not one of those times), but I am, as they say,

"comfortable" with the way it makes me look. The head is a good

shape-my head is not always a good shape in photographs-and the beard

is tidy

and the face has a certain lived-in melancholy that I can't deny I

recognize

from my mirror. The black Japanese raincoat looks great. The way the

subject of a photograph looks at the photograph is unlike the way

anyone else

will ever see it. You hope your worst bits haven't been emphasized too

much.

You hope not to look like a bag person. You hope not to scare people

who come

across the picture by chance. Let me try

to see this picture as if I were not its subject. Richard Avedon was

not

interested in making a picture of a cheery novelist without a care in

the

world. I think he wanted to make a portrait of a writer to whom a

number of bad

things had happened. I think the picture shows some of that pain, but

also, I

hope, it shows something of resistance and endurance. It is a strong

picture,

and I am grateful to Avedon, for his solidarity, for his picture's

clarity, and

for its strength. November

1995 Salman Rushdie:

Step Across This Line

|