|

|

|

A

Defense of Ardor

Writing in

Polish

People

sometimes ask me: "Why don't you write in English?" Or-if I'm in

France-why not in French? They clearly assume that I'd benefit, that

I'd do

better using some universal language instead of my provincial Polish.

And I

agree in principle; it would certainly be easier to write in some more

important language (if I could pull it off!). It reminds me of a story

about

George Bernard Shaw, who supposedly confessed in a letter to Henryk

Sienkiewicz

that he couldn't understand why the Poles didn't simply switch to

Russian. The

Irish had, after all, mastered English and were managing beautifully!

Really.

Writing in

Polish-in the nineteenth century, after the partitions-was an act of

patriotism. The Polish language was in grave danger, especially in the

Russian

sector. Today it's no longer a question. Even if he remembers his

city's

past-and such remembrance is in fashion these days-a young poet born in

Gdansk

won't hesitate in choosing which language to use. He only knows one,

after all.

Only someone like myself, who's lived abroad for years, meets up with

the-naive?-question of picking his language.

Adam Zagajewski

Note: Gấu

"đi" bài này, chủ yếu là để chửi lũ Mít bày đặt viết bằng tiếng mũi lõ!

Tính “đi”

lâu rồi!

Viết bằng tiếng Ba Lan

Người ta hỏi

tôi, tại sao không viết bằng tiếng Hồng Mao? Hay là - nếu tôi ở Tẩy,

tại sao

không chơi 1 đường tiếng... Đầm? Hẳn là họ yên chí, sẽ có lợi cho tôi

rất nhiều,

nếu sử dụng 1 thứ tiếng quốc tế thay vì đặc sản Ba Lan. Về nguyên tắc,

tôi OK. Viết bằng 1 thứ tiếng quan trọng

thì dễ dàng hơn nhiều (thì cứ giả dụ như tôi rất rành tiếng Anh, hoặc

tiếng Tẩy,

mà cho dù không rành cũng không sao, mướn 1 thằng nào đó viết cho mình,

dễ cái ợt,

văn bằng tiến sỡi của Thầy Kuốc hẳn là ở trong trường hợp này, hà, hà!)

Nó làm tôi

nhớ câu chuyện về Trạng Quỳnh. Một lần, ông viết thư cho 1

người bạn,

tỏ ý thắc mắc, tại sao tụi Mít không viết, và nói bằng tiếng… Tẫu?

Note: GCC

dịch

loạn. Thực sự, đây là 1 bài viết rất quan trọng, và có 1 cái gì đó,

khiến chúng

ta phải đọc, vì nó liên quan tới số phận Mít, và liên quan tới cuộc “đi

tìm nọc

độc văn hóa Mỹ Ngụy”, mà trong nước đang hăm hở, và nhờ thế, GCC được

đọc lại

đa số những bài viết ngày nào của mình.

A

Defense of Ardor Gray Paris

Paris,

photographed through thousands of lenses (Japanese tourists

experiencing a

moment of mechanized eternity on every bridge), consumed daily by the

greedy

gazes of the photographic devices deployed by tourists from various

continents,

has not ceased to exist ... It lives on, endlessly resisting the

onslaught of

gazes. There's the lighthearted Paris of song, the Paris of romantic

snapshots:

the stairs of Montmartre, the setting sun's rays on the Pont Neuf, the

autumn

leaves in the Luxembourg Garden, the frivolous Paris of films. But

there's also

another Paris.

All who've

come to this city by way of Europe's (or America's) provinces remember

the

first album of Parisian photos we viewed at a friend's or flipped

through with

a mixture of rapture and disdain while visiting some aunt or uncle:

rooftops on

the lie Saint-Louis, the church of Saint-Germain (the Romanesque style

blended

in this name with recollections of some Gothic Juliette Greco), a

gentle wave

on the gray Seine.

We leafed

through this album with a touch of scorn, since the longing to visit

this

mythical city was mixed with a vivid sense that these photographs,

intended

precisely for us provincials, were in fact classic tourist kitsch. I

don't know

why, but autumn always prevailed in those delicate, pastel pictures, as

if the

albums' editors knew that November's sweet warmth best captures

France's

capital.

The

best-known city in Europe ... So well known that newcomers from other

countries, nourished on movies, postcards, and those autumnal albums

above

which rises a slim, anorexic Eiffel Tower, scarcely feel any surprise:

we know

it, we know this place, they cry. We know that tower, the Parisian

rooftops, the

clipped boughs of the plane trees, the little trapezoidal squares on

which two

Paulownia trees grow. We know the cafe gardens and the little homes

nestled up

against Haussmann's showy structures. We know the metro line where, on

wintry

afternoons, you can stare directly into strangers' apartments-and the

imperial

facades of Napoleonic edifices.

To

photograph Paris-after all this! After painters, sketchers,

photographers,

after memoirists and writers! After Walter Benjamin and Paul Léautaud!

Is it

possible?

Apparently

so. You just have to try-and to possess a "point of view," not talent

and a good camera alone. I have before me the photographs of Bogdan

Konopka, depicting

a Paris I know well. At first glance, though, I can't seem to get my

bearings-I

don't know these houses, these court-yards, I don't know this derelict

railway

or this park sprinkled with snow. Where is the Place de la Concorde,

the

Boulevard Saint-Germain, where's my favorite bookshop, where's the

garden of

the Palais Royal with its young lindens? They're not here, I see only

anemic

little streets, flimsy houses, unprepossessing stairwells. Above all, I

don't

find the splendid Parisian light, the refulgence with which the oceanic

Atlantic climate repays Paris for the rain, the towering cumuli, the

cold and

damp it provides all winter, spring and fall. Bogdan Konopka's

photographs show

a faded city; paradoxically they too have something autumnal about

them, like

the more conventional albums I've mentioned. Here, though, the mute,

matte

still lifes of streets take the place of golden leaves and subtle

shadows: this

is actual, aggravating November.

I can

perfectly imagine the outrage of Paris's admirers, be they French or

foreign.

Where's the light? Where the Pont des Arts? I can hear the angry

voices: this

photographer's driven by malice. He's come from some small, dark

country, maybe

even a small, dark town in a small, dark country, and wants to strip

Paris of

its majestic light, its bright sandstone columns, its freshly scrubbed

Pantheon, its beautiful broad streets, the new pyramid in the Louvre's

courtyard, its splendid museums.

Does the

perpetrator of these photographs thus require a defense? And what shape

might

this plaidoyer take?

I see

several lines of potential defense. First, the counsel for the defense

might

appeal to the dominant aesthetic of today's photography, its muted

mood, as

well as the distinctive "turpism"-that is, an infatuation with

"ugliness" in both subject matter and its formal presentation-that

seems to typify the work of contemporary art photographers. And

certainly the

chief motive is resistance to commercial photography: photography's

beauty has

been hijacked, abducted by the cunning craftsmen of the camera, fashion

photographers, the creators of the covers for popular women's

magazines. They

don't lack for beauty: every page of Elle

or Vogue proudly displays lovely

photographs of lovely girls, lovely homes, lovely spring meadows above

which lovely

birds glide.

The counsel

for the defense might take into consideration the age's aesthetics. And

this

wouldn't be to the detriment of Konopka's work. Acknowledging the norms

of his

own historical moment doesn't discredit him in the least.

But the

defense must go further. It must prove that some- thing else is at

stake here.

Bogdan Konopka does this remark- able city a service by showing us

another

Paris, the Paris of courtyards and gray stairwells, the Paris of gloomy

afternoons. By evoking the secret fraternity of all cities, beautiful

and ugly,

he liberates Paris from the isolation into which it has been thrust by

its own

eminence, its unique status among the European capitals. Since how can

one live

a normal life, die a normal death in a Paris shown only from its

finest, most

glittering angle, displayed only in its most "imperial," elegant,

ministerial light?

Anyone who's

ever driven across the Czech Republic, Poland, or eastern Germany has

no doubt

seen boundlessly sad, gray towns and cities. Clearly Paris shares

nothing in

common with them, it's totally different-and yet, Konopka tells us in

his photographs'

calm voice, take a closer look at certain Parisian neighborhoods,

streets,

courtyards. And you'll perceive in them, as in an ancient mosaic,

fragments of

Mikolow and Pilsen, chips of Myslenice and East Berlin. This won't be

lèse-mjesté,

it's not attempted assassination; no, it's rather an effort to find

what the great

metropolis shares with a modest town on Europe's peripheries. It's an

attempt

to cast a bridge between the meek, the mundane, and imperial glory.

While

looking at these photographs, I also noticed that there's not a single

scrap of

the Paris erected by Baron Haussmann's titanic efforts. (I should

confess that

this Paris annoys me at times with its bourgeois regularity, the

solidity of

the buildings designed to house the Notary, the Physician, the

Engineer, the

Lawyer, the Pharmacist and the Dentist.) We're dealing here with the

pre- and

post-Haussmann Paris, a city still containing traces of organic

medieval

construction (as in the surviving islets of old Paris) as well as

modernity's

chaos.

Finally-as

Konopka's defense lawyer might conclude-the grayness of this Paris may

reflect

a certain disillusionment that is difficult, even shameful, to express,

the

disillusionment so well described by Czeslaw Milosz. Of course people

are still

enchanted by what is truly enchanting, and they still go on pilgrimage

to

Paris. But they also sense a certain lack. The city still exists, of

course, it

stands, washed by André Malraux, enhanced by new museums and monumental

structures, but the great light of intellect that once reigned here,

that drew

young writers and artists from throughout the world-Jerzy Stempowski

speaks

mournfully of a Central Laboratory that has closed up shop-has dimmed,

faded,

and even the eyes of cameras accustomed to registering other

parameters, more

physical in nature, can't help noticing. Bogdan Konopka took pictures

of Paris,

not its myth.

AZ

A Defense of Ardor

Intellectual

Krakow

The

structure of many European (and North American) cities is governed by a

mysterious law, which I have discovered and which may one day bear my

name.

Districts on the east side of town are generally proletariat in

character,

while western districts are bourgeois and comparatively intellectual.

Just take

a look at maps of London, Paris, Berlin, to name but a few

metropolises. Aren't

I right? The same pattern turns up time and again. In London we have,

as

everyone knows, the East and West Ends. In Paris, the wealthy sixteenth

district is on the west, while the humbler twelfth and twentieth

districts lie

eastward. The western suburbs are likewise safer and more prosperous

than their

eastern counterparts. West Berlin was the wealthy part of town long

before the

wall went up. This law also holds for Warsaw.

I've spoken

with knowledgeable geographers and sociologists who've been unable to

explain

this phenomenon. Does this peculiarity of city planning perhaps reflect

the

medieval principle of building churches along an east-west axis?

Krakow-a far

smaller town than the behemoths I've mentioned-is subject to the same

principle. The bourgeoisie and intellectuals have long since divided

the

territory west of the Market Square between them. Under communist rule

this

region grew grayer and became the kind of district that traditional

guidebooks

would be hard pressed to define. For Krakow's inhabitants, who don't

require

guidebooks, the answer was and remains simply "the intellectual

district."

West of

Market Square: that is, up Szewska Street past the Planty Gardens to

Karmelicka

Street and then Krolewska, and then along both sides of this axis, up

to Wola

Justowska. The intellectuals' apartments hid, and still hide, along

both sides

of Karmelicka Street in the quiet buildings on the side streets. The

editor

Jerzy Turowicz, who ran the Catholic newspaper Tygodnik Powszechny

wisely and

courageously for over fifty years, lived here until his death. The

novelist and

essayist Hanna Malewska lived here. Andrzej Kijowski was born here. The

philosopher Roman Ingarden lived a bit further down. As did the

historian

Henryk Wereszycki. The composer Wladyslaw Zelenski lived here before

then. And

there were many others. And who didn't live in the Writers' House on

Krupnicza

Street at one time or another? That's where the painter and writer

Stanislaw

Wyspianski was born as well. The splendid painters Jt zef Mehoffer and

Wojciech

Weiss also lived on Krupnicza. The Rostworowski family lived nearby on

Salwator.

Exceptions

do occur: the president of Polish poetry, and Polish intellectuals,

Czeslaw

Milosz lives not far from Market Square, but on the southeast side. The

poet

Ryszard Krynicki and his wife, the publisher Krystyna Krynicka, live

even

further off, across the Vistula River in Podgorze.

But let's

get back to the western territories: all these remarkable sites were

left in

ruins, or at least an advanced state of neglect, following the Nazi and

Stalinist years.

This is why,

seen with a cold, objective eye, these homes and streets don't seem to

conceal

any mystery. When my friend the American poet Edward Hirsch came to

Krakow in

the fall of 1996 to interview Wislawa Szymborska for The New York Times

Magazine-she'd just received the Nobel Prize-he called the area she

lived in

then (on Chocimska Street) "proletarian and nondescript."

Nondescript.

I was outraged and objected: I tried to explain that he hadn't

discerned the

streets' latent nobility, the delicate gleam of certain windows, the

charm of

their small parks, the possibilities contained by certain courtyards.

I realized

then that someone like myself who loves Krakow and has known it for

years must

perfect a complex system of perceptions. In other words, I understood

that I

saw the possibilities, the potentialities, the unfulfilled entelechies

of this

district, I sensed what it might become under more favorable

conditions. I knew

how many truly great artists had lived here (Wislawa Szyrnborska's

neighbors

for many years included the writer Kornel Filipowicz and the director

Tadeusz

Kantor; the director Krystian Lupa apparently still lives somewhere

nearby).

And I had mentally mixed their talents with the houses' unprepossessing

plaster. I also knew the district's past, I was familiar with its

history and

could imagine its bygone charms. At the same time few of its homes

could match

such expectations today. Even the famous "professors'" house at the

corner of Slowacki Boulevard and Lobzowska Street, where university

employees

once lived-it was nicknamed the "coffin" due to its black ceramic

facade-s-now blended into its banal surroundings.

My American

friend had seen only what really existed; a run-down district with

lopsided

sidewalks, streets full of pot- holes, buildings needing new plaster

with

drunks huddled in their doorways. Whereas I saw neighborhoods that had

given

birth to books, paintings, plays, and performances. I also some- times

knew, or

imagined with the help of books and the tales of older cousins, what

these

buildings and gardens had once been, and what they had held. But a new

arrival

from another, sober, empirical world could perceive only shabby, tired

objects.

The

venerable, medieval, Renaissance, or baroque Krakow is a different

matter: the

massive forms of churches and palaces don't need desperate feats of

imagination,

they're clearly defined against the sky's backdrop both day and

evening, as the

sun slowly descends. But the intellectual district demands a different

approach. Only visitors from other ex-communist countries can truly

understand

this, since they've witnessed the same process-the fading of cities.

They still

remember that certain cities, or perhaps just certain districts, can

best be

caught by way of sympathetic imagination, aided by a rudimentary

knowledge of

history: such spots escape the camera's objective eye.

Later I

thought that perhaps my mistake, my optimistic vision of the district

and my

reaction to my American friend's incomprehension, might be something

more than

an accidental optical or psychological phenomenon.

Perhaps we

view not only certain districts but even our country as such too

leniently,

expanding reality through reverie, enhancing a sometimes dreary

external world

by means of introspection.

Perhaps

that's why we have poetry.

A Defense of Ardor

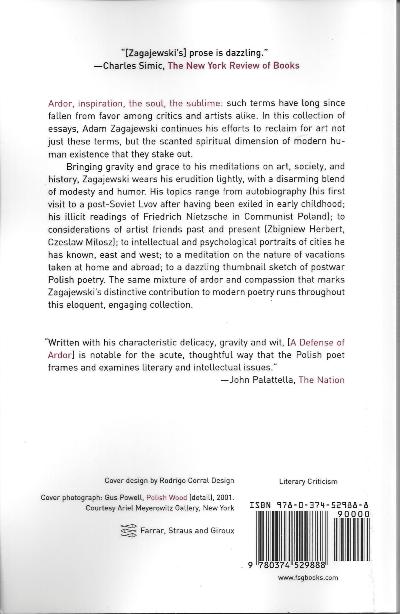

"[Zagajewski's]

prose is dazzling."

-Charles

Simic, The New York Review of Books

Ardor,

inspiration, the soul, the sublime: such terms have long since

fallen from

favor among critics and artists alike. In this collection of essays.

Adam

Zagajewski continues his efforts to reclaim for art not just these

terms. but the scanted spiritual dimension of modern human

existence that they stake out.

Bringing

gravity and grace to his meditations on art, society and history,

Zagajewski wears his erudition lightly, with a disarming blend of

modesty

and humor. His topics range from autobiography [his first visit to a

post-Soviet Lvov after having been exiled in early childhood; his

illicit

readings of Friedrich Nietzsche in Communist Poland]: to considerations

of artist friends past and present [Zbigniew Herbert, Czeslaw

Milosz]; to intellectual and psychological portraits of cities he has

known,

east and west; to a meditation on the nature of vacations taken at

home and abroad; to a dazzling thumbnail sketch of postwar Polish

poetry. The same mixture of ardor and compassion that marks

Zaqajewski's

distinctive contribution to modern poetry runs throughout this

eloquent. engaging collection.

"Written

with his characteristic delicacy, gravity and wit, [A Defense of Ardor] is

notable for the acute thoughtful way that the Polish poet frames and

examines literary and intellectual issues."

-John

Palattella. The Nation

Trong tập tiểu

luận này, Tin Văn đã giới thiệu 1 bài rồi, Trí tuyệt và những bông hồng.

Reason and

Roses

Adam Zagajewski

Nhưng có lẽ, ý nghĩa sâu

xa nhất của thái độ chính trị của Milosz thì nằm ở một nơi nào đó; theo

gót những bước chân của Simone Weil vĩ đại, ông mở ra cho mình một kiểu

suy nghĩ, nối liền đam mê siêu hình với sự nhủ lòng, trước số phận của

một con người bình thường.

Tuyệt!

[Note: Bạn để

ý, trong lời giới thiệu tập tiểu luận của AZ, Simic cũng nhắc

tới hai

từ “chìa khóa”, của Weil, trọng lực và ân sủng, gravity and grace: Bringing

gravity and grace to his meditations on art, society and history,

Zagajewski wears his erudition lightly, with a disarming blend of

modesty

and humor].

Milosz, giống như Cavafy

hay Auden, thuộc dòng những thi sĩ mà thơ ca của họ dậy lên mùi hương

của trí tuệ chứ không phải mùi hương của những bông hồng.

Nhưng Milosz hiểu từ trí

tuệ, reason, intellect, theo nghĩa thời trung cổ, có thể nói, theo

nghĩa “Thomistic” [nói theo kiểu ẩn dụ, lẽ dĩ nhiên]. Điều này có nghĩa

là, ông hiểu nó theo một đường hướng trước khi xẩy ra cuộc chia ly đoạn

tuyệt lớn, nó cắt ra, một bên là, sự thông minh, trí tuệ của những nhà

duy lý, còn bên kia là của sự tưởng tượng, và sự thông minh, trí tuệ

của những nghệ sĩ, những người không thường xuyên tìm sự trú ẩn ở trong

sự phi lý, irrationality.

Thơ

trí tuệ vs Thơ tình cảm

Tháng Mấy

gửi một người không quen…

Tháng Mấy rồi,

Em có biết?

tấm lịch sắp

đi vào ngõ cụt

ngày không

còn dông dài nói chuyện cũ

hàng cây

thưa lá cho nắng và gió tự do bông đùa

chiếc xe em

về đậu mỗi chiều

con đường dầy

thêm với lá

rung rúc còi

tàu không tìm được sân ga

những ngôi

nhà nhả khói

và đêm về thắp

đèn

Tháng Mấy rồi,

Em có biết?

chạy luống

cuống những buổi sáng muộn

ngày se lạnh

no tròn hạt sương sớm

đọng trên

mái tóc

nụ hôn sâu

trong đêm

những đổ vỡ

chảy dài theo cuốn lịch

mất tích

Tháng Mấy rồi,

Em có biết?

con sông

ngưng chảy

nheo mắt qua

những xa lộ

nhịp thở chậm

Rồi buổi chiều

cuối năm sẽ đến

ai bấm

chuông cửa vào giữa đêm

tuyết chắc

chắn sẽ rơi

và trời sẽ lạnh

vô cùng

Tháng Mấy rồi

sẽ qua

Vẫn còn một

người đợi em

Đài Sử

GCC lèm bèm:

Gấu mê nhất bài thơ này, của tác giả. Chữ

dùng tuyệt. Tình cảm đầy, nhưng giấu thật kín.

Làm nhớ tới ý thơ Lão Tử, thánh

[thi cũng được] nhân, thật bất nhân.

Coi loài người như ‘sô cẩu’.

Mặt lạnh

như tiền, nhưng trái tim thì nóng bỏng!

Đẩy tới cực điểm

ra ý của Kafka:

In the duel

between you and the world, back the world.

Trong trận đấu

sinh tử tay đôi giữa bạn và thế giới

[tha nhân, như GCC hiểu],

hãy hỗ trợ thế

giới

[Hãy đâm vào sau lưng bạn].

Bạn đọc TV

bi giờ chắc là hiểu ra tại làm sao, Gấu nằm dưới chân tượng Quan Công,

tỉnh dậy,

bò xuống sông Mekong tắm 1 phát, thấy cái xác của Gấu trôi qua!

Hà, hà!

Xạo tổ cha!

Già rồi mà nói

dóc quá xá!

Mé sau Chùa

Long Vân, Parsé.

Mé sau Chùa

Long Vân, Parsé.

Gấu nằm ngủ trưa dưới tượng Quan Công.

Dậy, xuống mé sông Mekong tắm.

|

|