The House of the Dead: Siberian Exile Under the Tsars.By Daniel Beer.Allen Lane; 487 pages; £30. To be published in America by Knopf in January.

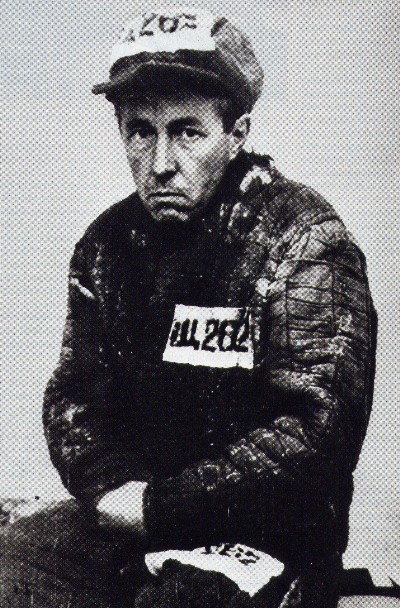

“HERE was a world all its own, unlike anything else,” wrote Fyodor Dostoevsky. Like hundreds of thousands of Russians before him, and many more after, Dostoevsky had been in Siberian exile, banished in 1850 to the “vast prison without a roof” that stretched out beyond the Ural mountains for thousands of miles to the Pacific Ocean. The experience marked him for ever. Siberia, he wrote later, is a “house of the living dead”.

It was no metaphor. In 19th-century Russia, to be sentenced to penal labour in the prisons, factories and mines of Siberia was a “pronouncement of absolute annihilation”, writes Daniel Beer in his masterly new history of the tsarist exile system, “The House of the Dead”. For lesser criminals, being cast into one of Siberia’s lonely village settlements was its own kind of death sentence. On a post of plastered bricks in a forest marking the boundary between Siberia and European Russia, exiles trudging by would carve inscriptions. “Farewell life!” read one. Some, like Dostoevsky, might eventually return to European Russia.

Successive tsars sought to purge the Russian state of unwanted elements. Later, as Enlightenment ideas of penal reform gained prominence, rehabilitation jostled with retribution for primacy. But the penal bureaucracy could not cope. The number of exiles exploded over the course of the 19th century, as an ever greater number of activities were criminalised. A century of rebellions, from the Decembrist uprising in 1825 to the revolution of 1905, ensured that a steady supply of political dissidents were carted across the Urals by a progressively more paranoid state. The ideals of enlightened despotism—always somewhat illusory—were swept away. Exiles re-emerged—if they ever did—sickly, brutalised and often violently criminal.

In the Russian imagination, the land beyond the Urals was not just a site of damnation, but a terra nullius for cultivation and annexation to the needs of the imperial state. Siberia, Mr Beer writes, was both “Russia’s heart of darkness and a world of opportunity and prosperity”. Exile was from the outset a colonial as much as a penal project. Women—idealised as “frontier domesticators”—were coerced into following their husbands into exile to establish a stable population of penal colonists. Mines, factories, and later grand infrastructure projects such as the trans-Siberian railway were to be manned by productive, hardy labourers, harvesting Siberia’s natural riches while rehabilitating themselves.

But in this, too, the system failed utterly. Unlike Britain’s comparable system of penal colonisation in Australia, the tsars never brought prosperity to Siberia. Fugitives and vagabonds ravaged the countryside, visiting terror on the free peasantry, Siberia’s real colonists. A continental prison became Russia’s “Wild East”.

In the end, the open-air prison of the tsarist autocracy collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions. The exiled and indigenous populations were engaged in low-level civil war, with resentful Siberian townsfolk up in arms protesting the presence of exiles thrust on them by the state. A land intended as political quarantine became a crucible of revolution. And modernisation—above all the arrival of the railway—ultimately turned the whole concept of banishment into an absurd anachronism. With revolution in 1917, the system simply imploded.

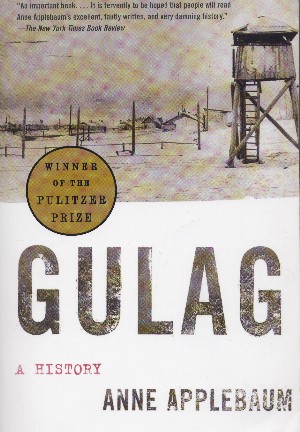

But it never really disappeared. The tsars’ successors, the Soviets, proclaimed lofty ideals but in governing such a vast land they, too, became consumed by the tyrannic paranoia that plagued their forebears. Out of the ashes of the old system rose a new one, the gulag, even more fearsome than what it replaced. Mr Beer’s book makes a compelling case for placing Siberia right at the centre of 19th-century Russian—and, indeed, European—history. But for students of Soviet and even post-Soviet Russia it holds lessons, too. Many of the country’s modern pathologies can be traced back to this grand tsarist experiment—to its tensions, its traumas and its abject failures.