|

|

A note on Beckett's French

Note: Gấu vẫn

nghĩ tay Auster này chỉ viết tiểu thuyết. Không ngờ viết phê bình tiểu

luận thật

ác. Nhất là những bài viết về thơ. TV sẽ giới thiệu tiếp, bài viết

về Già Ung, và về Celan: Thơ lưu vong, The poetry of Exile. Tuyệt.

Từ

Bánh tới Ðá Một ghi chú

về Tiếng Tây của Beckett. Mercier and Carnier là cuốn tiểu thuyết thứ nhất của Bekett viết

bằng tiếng Tây. Hoàn tất

vào năm 1946, nhưng được giữ lại không cho xb, tới 1970; nó cũng là

cuốn cuối,

trong những tác phẩm dài hơn, được chuyển qua tiếng Anh. Cái sự trễ nải

này có

vẻ như cho thấy, Beckett không mặn với nó. Giả như ông không bệ Nobel,

[mà ông đã từng than, thật là đại họa, khi được tin], có thể nó chẳng

được trình mặt với đời. Sự

dùng dằng này ở nơi tác giả, xem ra hơi bị lạ, bởi là vì, nếu nó là 1

tác phẩm

của thời kỳ di chuyển, thì liền lập tức, nó đưa chúng ta trở lại với Murphy and Watt, và khiến chúng ta hướng

tới những tuyệt tác của những năm đầu của thập niên 1950; tuy nhiên đây

quả là

một tác phẩm sáng chói, với những nét mạnh và quyến rũ của riêng nó,

chẳng bàn

cãi lôi thôi, đây không phải một tác phẩm lập lại, một phó bản, của bất

cứ một

trong sáu cuốn tiểu thuyết của Beckett. Ngay cả khi không ở đỉnh cao,

thì

Beckett vẫn là Beckett, và đọc ông, thì không như đọc, bất cứ 1 tay nào

khác. Nếu đếch có mẹ gì để nói,

thì nói mẹ làm gì. Camier Ðịa ngục, và nhất là Lò Luyện Ngục, vinh danh dáng đi của con người [nhất là cái dáng cao đen, đi nhẹ như đêm vào đời GNV, như đã từng được TCS vinh danh, “Từ vườn khuya bước về, bàn chân ai rất nhẹ, tựa hồn những năm xưa. Borges cũng tán về đoạn này, cũng nhắc tới Lò Luyện Ngục, y chang Mandelstam, qua câu thần sầu, BHD đi trong cái đẹp, như đêm: She walks in beauty, like the night] “Ðịa ngục, và đặc biệt Lò Luyện Ngục, vinh danh dáng đi của con người, nhịp điệu khi đi bộ, bàn chân và hình dáng của nó… Trong Dante, triết học và thơ ca thì vĩnh viễn hoài hoài ở trong cái thế chuyển động, dời đổi, vĩnh viễn trên đôi chân của chúng. Ngay cả khi đứng 1 chỗ, thì vẫn là ở trong cái thế chuyển động được tích tụ; làm 1 chỗ, tạo 1 chỗ cho con người đứng lại và trò chuyện, thì cũng gây phiền hà chẳng khác gì leo núi Alp.” Beckett, một trong những người đọc bảnh nhất của Dante, đã học được những bài học này tới chỉ. Hầu như huyền bí, văn xuôi của Mercier và Camier chuyển động dọc theo không gian tản bộ, và sau một lúc, người ta bắt đầu cảm thấy một cảm tưởng thật rõ rệt là đâu đó, chìm thật sâu ở trong những từ ngữ, một nhịp lặng bật ra từ những bước tản bộ của Mercier và Camier. Mercier and Carnier was the first of Samuel

Beckett's

novels to be written in French. Completed in 1946, and withheld from

publication until 1970, it is also the last of his longer works to have

been

translated into English. Such a long delay would seem to indicate that

Beckett

is not overly fond of the work. Had he not been given the Nobel Prize

in 1969,

in fact, it seems likely that Mercier and

Carnier would not have been published at all. This reluctance on

Beckett's

part is somewhat puzzling, for if Mercier and Carnier is clearly a

transitional

work, at once harking back to Murphy and Watt and looking forward to

the

masterpieces of the early fifties, it is nevertheless a brilliant work,

with

its own particular strengths and charms, unduplicated in any of

Beckett's six

other novels. Even at his not quite best, Beckett remains Beckett, and

reading

him is like reading no one else. Mercier and

Camier are two men of indeterminate middle age who decide to leave

everything

behind them and set off on a journey. Like Flaubert's Bouvard and

Pecuchet,

like Laurel and Hardy, like the other "pseudo couples" in Beckett's

work, they are not so much separate characters as two elements of a

tandem

reality, and neither one could exist without the other. The purpose of

their

journey is never stated, nor is their destination ever made clear.

"They

had consulted together at length, before embarking on this journey,

weighing

with all the calm at their command what benefits they might hope from

it, what

ills apprehend, maintaining turn about the dark side and the rosy. The

only certitude

they gained from these debates was that of not lightly launching out,

into the

unknown." Beckett, the master of the comma, manages in these few

sentences

to cancel out any possibility of a goal. Quite simply, Mercier and

Camier agree

to meet, they meet (after painful confusion), and set off. That they

never

really get anywhere, only twice, in fact, cross the town limits, in no

way

impedes the progress of the book. For the book is not about what

Mercier and

Camier do; it is about what they are. Nothing

happens. Or, more precisely, what happens is what does not happen.

Armed with

the vaudeville props of umbrella, sack, and raincoat, the two heroes

meander

through the town and the surrounding countryside, encountering various

objects

and personages: they pause frequently and at length in an assortment of

bars

and public places; they consort with a warm-hearted prostitute named

Helen;

they kill a policeman; they gradually lose their few possessions and

drift

apart. These are the outward events, all precisely told, with wit,

elegance,

and pathos, and interspersed with some beautiful descriptive passages

("The sea is not far, just visible beyond the valleys disappearing

eastward,

pale plinth as pale as the pale wall of sky"). But the real substance

of

the book lies in the conversations between Mercier and Camier: If we have

nothing to say, said Camier, let us say nothing. In a

celebrated passage of Talking about

Dante, Mandelstam wrote: "The Inferno and especially the Purgatorio glorify the human gait, the measure and rhythm of walking, the foot and its shape ... In Dante philosophy and poetry are forever on the move, forever on their feet. Even standing still is a variety of accumulated motion; making a place for people to stand and talk takes as much trouble as scaling an Alp." Beckett, who is one of the finest readers of Dante, has learned these lessons with utter thoroughness. Almost uncannily, the prose of Mercier and Camier moves along at a walking pace, and after a while one begins to have the distinct impression that somewhere, buried deep within the words, a silent metronome is beating out the rhythms of Mercier and Camier's perambulations. The pauses, the hiatuses, the sudden shifts of conversation and description do not break this rhythm, but rather take place under its influence (which has already been firmly established), so that their effect is not one of disruption but of counterpoint and fulfillment. A mysterious stillness seems to envelop each sentence in the book, a kind of gravity, or calm, so that between each sentence the reader feels the passing of time, the footsteps that continue to move, even when nothing is said. "Sitting at the bar they discoursed of this and that, brokenly, as was their custom. They spoke, fell silent, listened to each other, stopped listening, each as he fancied or as bidden from within." This notion

of time, of course, is directly related to the notion of timing, and it

seems

no accident that Mercier and Camier immediately precedes Waiting

for Godot in Beckett's oeuvre. In some sense, it can be

seen as a warm-up for the play. The music-hall banter, which was

perfected in

the dramatic works, is already present in the novel: What will it

be? said the barman. But whereas Waiting

for Godot is sustained by the

implicit drama of Godot's absence - an absence that commands the scene

as

powerfully as any presence - Mercier and Camier progresses in a void.

From one

moment to the next, it is impossible to foresee what will happen. The

action,

which is not buoyed by any tension or intrigue, seems to take place

against a

background of nearly total silence, and whatever is said is said at the

very

moment there is nothing left to say. Rain dominates the book, from the

first

paragraph to the last sentence (" And in the dark he could hear better

too, he could hear the sounds the long day had kept from him, human

murmurs for

example, and the rain on the water") an endless Irish rain, which is

accorded the status of a metaphysical idea, and which creates an

atmosphere

that hovers between boredom and anguish, between bitterness and

jocularity. As

in the play, tears are shed, but more from a knowledge of the futility

of tears

than from any need to purge oneself of grief. Likewise, laughter is

merely what

happens when tears have been spent. All goes on, slowly waning in the

hush of

time, and unlike Vladimir and Estragon, Mercier and Camier must endure

without

any hope of redemption. The key word

in all this, I feel, is dispossession. Beckett, who begins with little,

ends

with even less. The movement in each of his works is toward a kind of

unburdening, by which he leads us to the limits of experience - to a

place

where aesthetic and moral judgments become inseparable. This is the

itinerary

of the characters in his books, and it has also been his own progress

as a

writer. From the lush, convoluted, and jaunty prose

of More Pricks than Kicks (1934) to

the desolate spareness of The Lost Ones

(1970), he has gradually cut closer and closer to the bone. His

decision thirty

years ago to write in French was undoubtedly the crucial event in this

progress. This was an almost inconceivable act. But again, Beckett is

not like

other writers. Before truly coming into his own, he had to leave behind

what

came most easily to him, struggle against his own facility as a

stylist. Beyond

Dickens and Joyce, there is perhaps no English writer of the past

hundred years

who has equaled Beckett's early prose for vigor and intelligence; the

language

of Murphy, for example, is so packed that the novel has the density of

a short

lyric poem. By switching to French (a language, as Beckett has

remarked, that

"has no style"), he willingly began all over again. Mercier and

Carnier stands at the very beginning of this new life, and it is

interesting to

note that in this English translation Beckett has cut out nearly a

fifth of the

original text. Phrases, sentences, entire passages have been discarded,

and

what we have been given is really an editing job as well as a

translation. This

tampering, however, is not difficult to understand. Too many echoes,

too many

ornate and clever flourishes from the past remain, and though a

considerable

amount of superb material has been lost, Beckett apparently did not

think it

good enough to keep. In spite of

this, or perhaps because of this, Mercier

and Carnier comes close to being

a flawless work. As with all of Beckett's self-translations, this

version is not

so much a literal translation of the original as a re-creation, a

"repatriation" of the book into English. However stripped his style

in French may be, there is always a little extra something added to the

English

renderings, some slight twist of diction or nuance, some unexpected

word

falling at just the right moment, that reminds us that English is

nevertheless

Beckett's home. George, said

Camier, five sandwiches, four wrapped and one on the side. You see, he

said,

turning graciously to Mr Conaire, I think of everything. For the one I

eat here

will give me the strength to get back with the four others. There is a

crispness to this that outdoes the French. "Sophistry" for

"raisonnement du clerc," "crusts" for "pain see,"

and the assonance with 'mustard' in the next sentence give a neatness

and

economy to the exchange that is even more satisfying than the original.

Everything

has been pared down to a minimum; not a syllable is out of place. We move from

cakes to stones, and from page to page Beckett builds a world out of

almost

nothing. Mercier and Camier set out on a journey and do not go

anywhere. But at

each step of the way, we want to be exactly where they are. How Beckett

manages

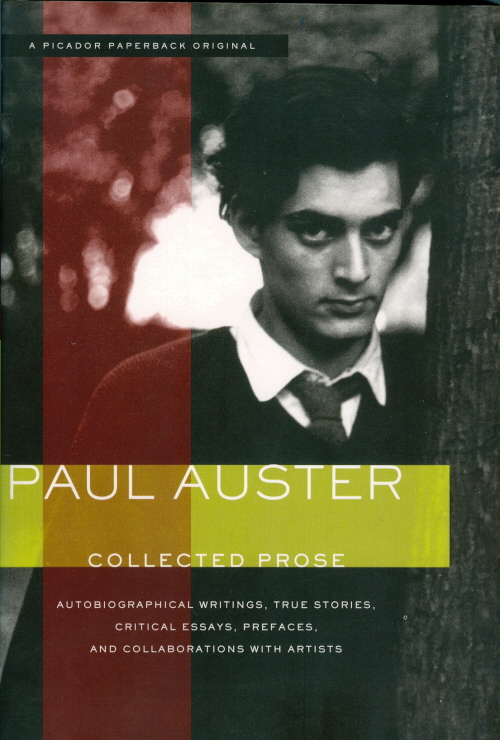

this is something of a mystery. But as in all his work, less is more. 1975 Paul Auster:

CRITICAL ESSAYS

|