|

Cái

gì nối

vòng tay lớn, những tiểu thuyết gia lớn lao này, vượt ra khỏi biên

cương, bờ luỹ,

xứ sở, quốc gia của họ? Hai điều thiết yếu, cơ bản của tiểu thuyết ...

và xã hội.

Sự tưởng tượng và ngôn ngữ. Chúng trả lời câu hỏi về điều phân biệt

tiểu thuyết

với báo chí, khoa học, chính trị, kinh tế và ngay cả với điều tra triết

học. Chúng

đem “thực tại chữ”, tới cho cái phần thế giới chưa được viết ra. Và chúng cùng chia sẻ nỗi sợ khẩn thiết của tất

cả những tác giả văn chương: Nếu ta, một thằng như thằng cha GCC, thí

dụ, đếch

viết "từ" đó, thí dụ, Cái Ác Bắc Kít, lên trang Tin Văn, là sẽ đếch có

thằng chó nào khác, viết!

Nếu GCC

không thốt ra "từ" đó, lời đó, thế giới sẽ rơi vào câm lặng (hay là vào

tầm phào,

ngồi lê đôi mách, và giận dữ). Và 1 "từ"

không viết ra, kết án tất cả chúng ta chết câm nín, và bất bình, đếch

hài lòng.

Chỉ có cái gì nói ra thì thiêng liêng, đếch nói đếch thiêng. Bằng cái việc nói

điều gì đó, tiểu thuyết làm

cho thấy, khía cạnh không thấy, của thực tại của chúng ta. Và nó làm

như vậy

theo một cách thức hoàn toàn không thể tiên đoán được, bằng những tiêu

chuẩn hiện

thực hay tâm lý, của quá khứ. Sửdụng "tới chỉ", cách thức, phương pháp,

của

Bakhtin, tiểu thuyết gia sử dụng giả tưởng như là 1 đấu trường, và

những nhân vật

xuất hiện, trang bị đủ thứ khí giới, nào ngôn ngữ, nào luật ứng xử…. mở

rộng mảnh

đất, nơi con người hiện diện trong lịch sử. Tiểu thuyết sau cùng làm

cho trở thành

thích ứng, chiếm hữu cái điều mà trước đó, nó không là: báo chí,

triết học… Nếu gọi tên

hai nhà văn Pháp, một trong quá khứ một ở

hiện tại, mà chị ngưỡng mộ hoặc đồng cảm thì đó là ai ? Chị muốn nhìn

thấy nhà

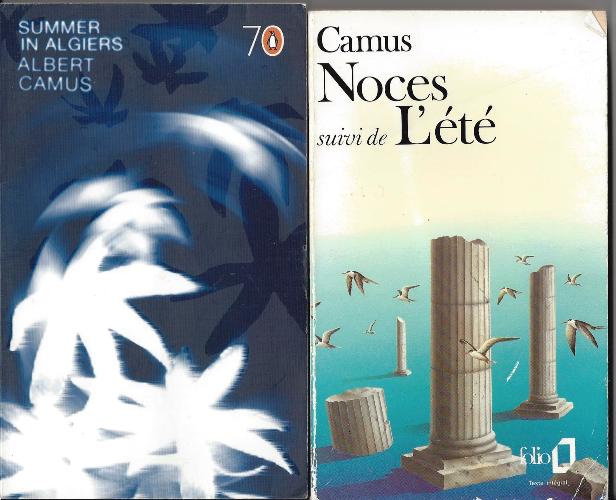

văn Pháp nào hoặc tiểu thuyết Pháp nào được dịch ở Việt Nam ? Camus - ngắn

gọn, chính xác và bình thản. Houellebecq - sắc sảo, hài hước và khiêu

khích. Với

tôi, đó là hai cách thể hiện độc đáo cho cùng một đề tài không ngừng

được khai

thác trong văn chương - sự phi lý của nhân gian. Camus là tác

giả của thời mới lớn của Gấu, và của những người cùng tuổi Gấu, và, có

thể dùng

1 câu của ông, để diễn tả cái thời đó, với 1 chút thay đổi: Bữa trước, đọc

SCN, thấy khoe, hai tác giả gối mông [từ này là của em NT] là Nabokov

và Kafka,

GCC đã sững sờ, một ông thiện và một ông ác, cùng tranh mông của 1 em

Mít. Camus thì cả

nhân loại quí, và... chịu. Còn ông

Houellebecp, đến mẹ của ông ta cũng không chịu nổi, chính thằng con của

bà, vậy

mà cùng tranh tí mông Mít, sao?

TV sẽ chuyển

ngữ bài viết “Trở về Tipsapa: Return to Tipasa”. (a) Return

to Tipasa

'You have

navigated with raging soul far from the Noces, thì đã được ông Tẩy mũi tẹt TTD chuyển qua tiếng Mít là Giao Cảm. August 12,

2013 Translator’s

note:

—Ryan Bloom “Đời nghệ sĩ”,

kịch Camus, lần đầu tiên xuất hiện trên 1 tờ báo bèo ở Algeria, Tháng

Hai,

1953, nay được đưa vô ấn bản toàn bộ tác phẩm Pléiade, và được coi như

là phụ lục

của tuyển tập truyện ngắn Lưu Đày và

Quê Nhà. How is one to be a pure, authentic artist and live in a world that corrupts and destroys purity? Làm sao 1 nghệ sĩ, thứ

thật trong trắng, thật chân thực, lại có thể sống trong

1 thế giới nhơ bẩn như hiện nay? (a) Toi tinh

viet 1 cuon tieu thuyet! -Anh

Trụ tính

chi thì làm đi, cứ hẹn dịch bài này, sách nọ mà rồi chả thấy mô hết! Nhưng không thể nào ngờ được, Trái Tim, Tâm, Bếp Lửa... của dân Mít, sau cùng lòi ra... bộ mặt thực: Trái Tim Của Bóng Đen! Bếp Lửa trong văn chương Novel What can the

novel say that cannot be said in any other manner? This is the very

radical

question asked by Hermann Broch. It is answered, specifically, by a

constellation of novelists so extensive and so diverse that together

they offer

a newer, broader, and even more literal notion of the dream of

Weltliteratur,

the world literature that Goethe envisioned. If, as French critic and

novelist

Roger Caillois said, the first half of the nineteenth century belonged

to

European literature, then the second half belonged to the Russians,

while the

first half of the twentieth century belonged to the North Americans,

and the

second half to the Latin Americans. Then, at the dawn of the

twenty-first

century, we can speak of a universal novel that encompasses Gunter

Grass, Juan

Goytisolo, and Jose Saramago in Europe; Susan Sontag, William Styron,

and

Philip Roth in North America; Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Nelida Pinion,

and Mario

Vargas Llosa in Latin America; Kenzaburo Oe in Japan; Anita Desai in

India;

Naguib Mahfouz and Tahar Ben-Jeleum in North Africa; and Nadine

Gordinier, J.

M. Coetzee, and Athol Fugard in South

Africa. Nigeria alone, from the “heart of darkness” of the shortsighted

Eurocentric conceptions, has three great narrators: Wole Soyinka,

Chinua

Achebe, and Ben Okri. What is it that unifies

these great novelists beyond their

respective nationalities? Two things that are essential to the novel.

... and

society. Imagination and language. They answer the question of what

distinguishes the novel from journalistic, scientific, political,

economic, and

even philosophical inquiry. They give verbal reality to that part of

the world

that is unwritten. And they all share the urgent fear of all authors of

literature: if I don't put this word down on paper, nobody else will.

If I

don't utter this word, the world will fall into silence (or gossip and

fury).

And a word unwritten or unspoken condemns us all to die mute and

discontent.

Only that which is spoken is sacred; unspoken, unsacred. By saying

something,

the novel makes visible the invisible aspect of our reality. And it

does so in

a manner that is entirely unforeseeable by the realistic or

psychological

canons of the past. To the full (plenipotentiary) manner of Bakhtin,

the

novelist employs fiction like an arena in which characters appear along

with

language, codes of conduct, the most remote historical moments, and

multiple

genres, causing artificial walls to crumble, endlessly broadening the

territory

of human presence in history. The novel ultimately appropriates the

very thing

that it is not: science, journalism, philosophy ... For this reason the novel

is much more than a reflection of

reality; it creates a new reality, one that did not exist before (Don

Quixote,

Madame Bovary, Stephen Dedalus) but without which we could not imagine

reality

as we know it. As such, the novel creates a new kind of time for

readers. The

past is rescued from the museums, and the future becomes an

unattainable

ideological promise. In the novel, the past becomes memory and the

future,

desire. Yet both occur in the now, in the present time of the reader

who, by

reading, remembers and desires. Today, Don Quixote will go out to fight

the

windmills that are giants. Today, Emma Bovary will enter the pharmacy

of the

apothecary Homais. Today, Leopold Bloom will live through a single June

day in

the city of Dublin. William Faulkner put it best when he said that time

was not

a continuation, it was an instant: "There was no yesterday and no

tomorrow, it all is this moment." In this

light, the reflection of the past appears as the prophecy of the

narrative of the

future. The novelist, far more punctual than the historian, always

tells us

that the past has not yet ended, that the past must be invented at

every hour

of the day if we don't want the present to slip from our grasp. The

novel

expresses all the things that history either did not mention, did not

remember,

or suddenly stopped imagining. One example of this is found in

Argentina-the

Latin American country with the briefest history but the greatest

writers.

According to an old joke, the Mexicans descended from the Aztecs, and

the

Argentinians from the boats. Precisely because it is a young country,

with

relatively recent waves of immigration, Argentina has had to invent a

history

for itself, a history beyond its own, a verbal history that responds to

the lonely,

desperate cry of all the world's cultures: please, verbalize

me. Borges, of course, is the

most fully developed example of

this "other" historicity that compensates for the lack of Mayan ruins

and Incan belvederes. In the face of Argentina's two horizons - the

Pampa and

the Atlantic-Borges responds with the total space of "The Aleph," the

total time of "The Garden of the Forking Paths," and the total book

in "The Library of Babel," not to mention the uncomfortable

mnemotechnics of "Funes, the Memorious." History as absence.

Nothing else inspires quite so much fear.

But nothing provokes a more intense response than the creative

imagination. The

Argentine writer Hector Libertella offers the ironic response to such a

dilemma. Throw a bottle into the sea. Inside the bottle is the only

proof that

Magellan circumnavigated the earth: Pigafetta's diary. History is a

bottle

thrown into the sea. The novel is the

manuscript found inside the bottle. The remote Past meets the most

immediate

present when, oppressed by an abominable dictatorship, an entire

disappear, to

be preserved only in novels, such as those by Luisa Valenzuela of

Argentina or

Ariel Dorfman of Chile. Where, then, do the marvelous historical

inventions of

Tomas Eloy Martinez (The Peron Novel and

Santa Evita) occur? In Argentina's necrophiliac political past? Or

in an

immediate future in which the author's humor enables the past to become

the

present-that is, presentableand, more than anything, legible? I would like to believe

that this mode of fictionalization

fills a need felt by the modern (or postmodern, if you wish) world.

After all,

modernity is a limitless proposition, perpetually unfinished. What has

changed,

perhaps, is the perception expressed by Jean Baudrillard that "the

future

has arrived, everything has arrived, everything is here." This is what

I

mean when I speak of a new geography for the novel, a geography in

which the

present state of literature dwells and that cannot be understood-in

England,

let's say-unless one is aware of the English-language novels written by

authors

with multiracial and multicultural faces, who belong to the old

periphery of

the British Empire – i.e., the Empire Writes Back. V S. N aipaul, an Indian

from Trinidad; Breyten Breitenbach,

a Dutch Boer from South Africa; but also Marie-Claire Blais, of

francophone

Canada, and Michael Ondaatje, a Canadian as well though via Sri Lanka.

The

British archipelago includes other internal and external islands:

Alasdair

Gray's Scotland, Bruce Chatwin's Wales, or Edna O'Brien's Ireland, all

the way

to Kazuo Ishiguro's Japan. There would be no North American novel to

broaden

the. diversity of culture, race, and gender without the African

American Toni

Morrison, the Cuban American Cristina Garcia, the Mexican American

Sandra

Cisneros, the Native American Louise Erdrich, or the Chinese American

Amy Tan.

They are all modern Scheherazades: each night as they tell their tales,

they

stave off our deaths one more day .... Jean-Francois Lyotard

tells us that the Western tradition has

exhausted what he calls "the meta-narrative of liberation." But

doesn't that mean, then, that the end of those "meta-narratives" of

the modern Enlightenment signals the multiplication of the

"multi-narratives" that have emerged out of a poly-cultural and

multiracial universe that transcends the exclusive domain of Western

modernity? Perhaps Western

modernity's "incredulity toward meta-

narratives" is being displaced by the credibility being gained by the

poly-narratives

that speak on behalf of the multiple efforts for human liberation, new

desires,

new moral demands, and new territories of human presence throughout the

world. This "activation of

differences," as Lyotard calls

it, is simply another way of saying that despite the realities of

globalization,

our post-Cold War world (and, if Bush Jr. gets his way, a world of

white-hot

peace) is not moving toward one illusory and perhaps very damaging

unity but

rather toward a greater, healthier, though often more contentious

differentiation of its peoples. I say this as a Latin American. For

much of our

independent existence, we were absorbed by a nationalistic

preoccupation with

identity-from Sarmiento to Martinez Estrada in Argentina, from Gonzalez

Prada

to Mariategui in Peru, from Hostos in Puerto Rico to Redo in Uruguay,

from

Fernando Ortiz to Lezama Lima in Cuba, from Henriquez Urena in Santo

Domingo to

Picon Salas in Venezuela, from Reyes to Paz in Mexico, Montalvo in

Ecuador, and

Cardoza Aragon in Guatemala. And this did, in fact, help give us

exactly that:

an identity. No Mexican has any doubt as to whether he is a Mexican, no

Brazilian doubts he is a Brazilian, no Argentinian doubts he is

Argentinian.

This reward, however, comes with a new demand: that of moving from

identity to

diversity. Moral, political, religious, sexual diversity. Without

respect for

the diversity that is based upon identity, liberty cannot exist in

Latin

America. I offer the example that

is closest to me, the Indo-Afro-Latin

American example, to support the argument that sees the novel as a

factor in

cultural diversification and multiplicity in the twentieth century. We

enter

the world that Max Weber heralded as "a polytheism of values."

Everything-communications, economics, science, and technology but also

ethnic

demands, revived nationalism, the return of tribes and their idols, the

coexistence between exponential progress, and the resurrection of all

that we thought

was dead. Variety and not monotony, diversity rather than uniformity,

conflict

rather than tranquility will define the culture of our century. The novel is a

reintroduction of the human being in history.

In the greatest of novels, the subject is introduced to his destiny,

and his

destiny is the sum of his experience: fatal and free. In our time,

however, the

novel is a kind of calling card that represents the cultures that, far

from

having been drowned by the tides of globalism, have dared to affirm

their

existence more emphatically than ever. Negative in the terms we are all

familiar with (xenophobia, aggressive nationalism, cruel primitivism,

the

perversion of human rights in the name of tradition, or the oppression

by the

father, the macho, the clan), idiosyncrasy is positive when it affirms

values

that are in danger of being forgotten or eliminated and that, in and of

themselves, are bulwarks against the worst tribalistic instincts. There is no novel without

history. But the novel, by introducing

us to history, also allows us to search the non-historical path so that

we may

contemplate history in a clearer light, so that we may be authentically

historical. To become so immersed in history that we lose our way in

its

labyrinths, unable to find our way out, is to become a victim of

history. Insertion of the

historical being into history. Insertion of

one civilization into others. This will require a keen conscience on

the part

of our own tradition if our goal is to extend a welcoming hand to the

traditions of others. What unites all tradition if not the need for

building a

new creation upon it? This is the question that new Mexican novelists

like

Jorge Volpi, Ignacio Padilla, and Pedro Ángel Palou resolve so

brilliantly. All novels, like all works

of art, are composed

simultaneously of both isolated and continuous instants. The instant is

the

epiphany that, with luck, every novel captures and liberates. As Joyce

puts it

in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young

Man, they are delicate, fugitive moments, "lightning’s of

intuition" that strike "in the midst of common lives." But they also strike us in

the middle of a continuous

historical event, so continuous that it has neither beginning nor

ending,

neither theological origin nor happy ending nor apocalyptic finale,

just a

declaration of the interminable multiplication of meaning that opposes

the

consoling unity of one single, orthodox reading of the world. "History

and

happiness rarely coincide," wrote Nietzsche. The novel is proof of

this,

and in Latin America we gain the novel of mindful warning when we lose

the

discourse of hope. New novel: I speak of a

still tentative but perhaps necessary

step, from identity to "alternity"; from reduction to enlargement;

from expulsion to inclusion; from paralysis to movement; from unity to

difference; from non-contradiction to perpetual contradiction; from

oblivion to

memory; from the inert past to the living past; from faith in progress

to

criticism of the future. These are the rhythms, the

meanings of newness in narrative....

perhaps. But only with them, with all the works that liberate them, can

we

attain the magnificent potential for creating images that Jose Lezama

Lima

bestowed upon the "imaginary eras." Because if a culture is not able

to create an imagination, the result will be historically

indecipherable, adds

the author of Paradiso. The novelty of the novel

tells us that humanity does not live

in an icy abstraction of the separate, but in the warm pulse of an

infernal

variety that tells us: we have yet to be. We are in the process of

becoming. That voice questions us,

arriving from far away but also from

very deep within us. It is the voice of our own humanity revealed in

the

forgotten boundaries of the conscience. And it hails from multiple

times and

distant spaces. But it creates-with us, for us-a space where we can

gather

together and share our stories with one another. Imagination and language,

memory and desire-they are not only

the living matter of the novel but the meeting place for our unfinished

humanity as well. Literature teaches us that the greatest values of all

are

those that we share with others. We Latin American novelists share

Italo

Calvino's sentiments when he declares that literature is a model of

values,

capable of proposing stages of language, vision, imagination, and

correlation

of events. We see ourselves in William Gass when he shows us that the

body and

the soul of a novel are its language and imagination, not its good

intentions:

the conscience that the novel alters, not the con- science that the

novel

comforts. We identify with our great friend Milan Kundera when he

reminds us

that the novel is a perpetual redefinition of the human being as

problem. All of this implies that

the novel must formulate itself as a

constant conflict of all that has yet to be revealed, as a remembrance

of all

that has been forgotten, the voice of silence and wings of desire of

all that

has been overcome by injustice, indifference, prejudice, ignorance,

hatred, and

fear. To achieve this, we must

look at ourselves and the world

around us as unfinished projects, permanently incomplete personalities,

voices

that have not yet uttered their last word. To achieve this, we must

tirelessly

articulate a tradition and uphold the possibility that we are men and

women who

not only exist in history but make history. As Kundera suggests, a

world in the

midst of rapid transformation invites us constantly to redefine

ourselves as

problematic, perhaps even enigmatic beings, never as the bearers of

dogmatic

answers or conclusive realities. Isn't this what best describes the

novel?

Politics can be dogmatic. The novel can only be enigmatic. The novel earns the right

to criticize the world by proving, firstly,

its ability to criticize itself. The novel's criticism of the novel is

what

reveals the labor that goes into this art as well as the social

dimension of

the work. James Joyce in Ulysses and Julio Cortazar in Rayuela

(Hopscotch) are prime examples of what I am trying to say:

the novel as a criticism of itself and the manner in which it unfolds.

But this

is the legacy of Cervantes and the novelists of La Mancha. The novel proposes the

possibility of a verbal vision of

reality that is no less real than history itself. The novel always

heralds a

new world, an imminent world. Because the novelist knows that after the

terrible, dogmatic violence of the twentieth century, history has

become a

possibility; never again can it be a certainty. We think we know the

world.

Now, we must imagine it. Carlos Fuentes: This I

Believe. An A to Z of a Life. |