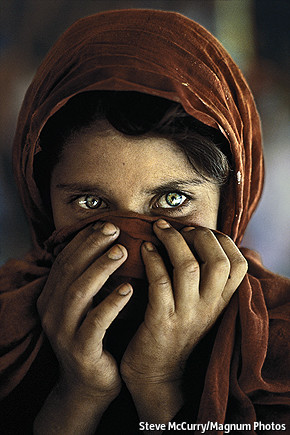

WHO could forget those piercing green eyes staring out from a ragged, rust-coloured scarf on the cover of the June 1985 issue of National Geographic? Taken nearly 30 years ago by Steve McCurry, an American photojournalist, this memorable photograph, known as the "Afghan Girl", has remained embedded in people’s minds.

Mr McCurry recounts the story behind this photo and others in his new book, “Steve McCurry Untold: The Stories Behind the Photographs”. In this chronicle of past assignments, from his time in Kuwait after the Gulf War to his efforts to capture the human side of a conflict in Kashmir, Mr McCurry uses journal entries, letters and travel receipts to add depth and context to his memorable work. He spoke to The Economist about creating the book, his reunion with the Afghan girl and the future of photojournalism.

How did the idea for the book come about?

I thought it would be interesting to tell the stories behind the pictures. So many of my other books have been primarily photographs, so I wanted to talk about my process and the back story to how these pictures came about, such as the circumstances during the monsoon in Afghanistan when the conflict first began, 9/11 and that sort thing.

What was it like retelling the images you captured through words?

You go over your recollections, you go over notes, you try and recall that time and the situation, and things come back to mind, things you hadn’t really thought about or articulated. I thought it was a good exercise to actually get those experiences down on paper for the record.

Why did you think Sharbat Gula, the "Afghan Girl", was so special? Did you have any idea that the photograph would become so iconic?

I knew it was a powerful image. I knew that she had a powerful presence. She was very striking. I knew all that, but I never dreamed it would be on the cover of the magazine, much less become an icon of the [Soviet] war in Afghanistan or Afghan refugees. The power of the picture has to do with her eyes and the ambiguity of her expression. There are a lot of emotions in that picture; on the one hand she seems a bit traumatised, but there’s a real sense of dignity and fortitude and perseverance. She’s a beautiful little girl, but there is also dirt on her face and her clothes are torn, yet she holds a direct gaze at the camera.

How was your reunion 17 years later?

It was extraordinary. It was astonishing that she and her husband agreed to meet with us, which was really unusual in that culture. We were thrilled that she was still alive, that she had a good life, that we were able to finally give back to her and help her. I think she was a bit bewildered by the whole thing initially. She didn’t understand that her picture has been published all over the world. But in time she learned—we provided her with a television so she could see the documentary [“Search For the Afghan Girl” (2003)].

We keep in touch with her every month—myself, National Geographic, my sister plays a very important role in maintaining this relationship and assisting her with all sorts, whether it’s medical assistance, education, housing or anything we can do. We’ve helped to buy her a home that she’s able to have ownership of. It’s been great to help her. I believe that this has made her life better.

Is it difficult to keep yourself emotionally separate from your subjects?

You can have an opinion, and you can be emotional about a situation. But even though you might have very strong opinions I think you have to tell an honest, accurate and fair story.

How has digital photography and the internet changed photojournalism?

We got comfortable with the world of magazines and newspapers and the big assignments, but that status quo has been challenged. Now virtually any photographer can self-publish his or her work on the internet and get it out there. Of course the magazines are cutting back and some of them are disappearing. Photo staffs have been cut. But it’s inevitable and you have to look at it as a huge opportunity. People have to figure out a way to move forward, but there’s no point in mourning the past, because it’s just a new day.

Any plans to retire soon?

Well you never retire. It’s just not even remotely part of my thought process. It would be like if I were to stop breathing or to stop eating. This is my passion, this is what gives me purpose in life and I would never even remotely consider giving that up.

Steve McCurry Untold: The Stories Behind the Photographs. By Steve McCurry. Phaidon; 320 pages; $59.95