|

Advertisement

|

|

|

ATTEMPTS to make art out of recent political events often feel more gauche than “Guernica”. The Bush-era war on terror may have captivated our collective imagination, but few have been able to grapple with its moral complexities in art. With the passage of time, though, the human element—compelling, empathetic portraits of both perpetrators and victims—will doubtless re-emerge, and outlast any political bromides.

Laura Poitras, a film-maker based in New York, premiered her show “Astro Noise” earlier this year. An acclaimed and immersive exploration of the post-9/11 surveillance state, it questioned viewers’ complicity by having them watch footage of their fellow patrons. Yet her prominent role in assisting Edward Snowden’s 2013 revelations risks confusing these earnest pieces for polemic. Edmund Clark’s new exhibition, “War of Terror”, at the Imperial War Museum in London takes a different approach. It suggests that an enduring representation of the period may not lie in furious condemnation: it may be closer to the word “Kafkaesque”.

The word is overused, but never has an exhibition come closer to capturing the feeling of being trapped in a huge, absurd, unfeeling bureaucratic system. Kafka’s works never condemn perpetrators outright, but see evil in the system simply doing its job. By portraying the anti-terror apparatus as such a piece of madness, Mr Clark finds a clear visual language with which to portray the war’s inhumanity. Few grandstanding gestures are made: the vast accumulation of evidence does all the talking.

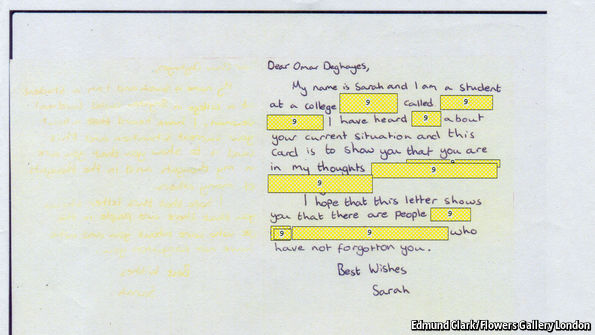

In an extraordinary section we are shown the mail of Omar Deghayes, a British Guantanamo detainee, as redacted by prison officials. The censorship choices are so bizarre that messages of support take on new, abstract meanings. Entire pages are obscured under heavy grey rectangles; images of British landmarks become devoid of context, a reference to a “sexy Leslie” puzzlingly orphaned. These are artistic pieces created not by an individual, but by a mindless process, something Mr Clark has been canny enough to display without comment. By arranging redaction as a piece of art, Mr Clark suggests that the absurdity of the situation might itself become a form of torture: as the detainee’s concept of a reality outside his cell becomes ever more distorted, he starts to question his own sanity. Kafka, no doubt, would have sympathised.

The detail of these exhibits is overwhelming. It takes a while to notice that some affectless internal office communication refers to force feeding chairs, photographs of which are blown up in clinical detail. The correspondences on display are the unflinching discussions of people simply doing the job in front of them. Even during extraordinary rendition, much ink is spilt in making sure the subject has the proper passport stamps. Mr Clark has remarkable sympathy for the day-to-day personnel involved, but his portrayal is one of a system going slowly insane.

The best examination of this madness is not, however, to be found in Guantanamo. It is to be found in suburban England, where Mr Clark documents the life of a terrorism suspect under a Home Office control order. As opposed to the more sensational abuses committed elsewhere in this “war”, here we have a system that simply does not know what to do about the threats it faces. The conditions of his curfew are displayed like a student house’s tenancy agreement: no noise after 10pm, no pets. The unspoken implication is that the suspect would somehow be guiltier of terrorism if he contravened them—the sort of surreal legalistic jump that wouldn’t be out of place in “The Trial”.

It is the diary of this anonymous suspect that provides the clinching image of the whole exhibit. He reports on the tedium of the limbo that the state has left him in: “My curfew is over so I go outside and buy a donut.” The tiny detail—that he buys his breakfast from Greggs, a popular British bakery chain—seems to bring the whole period into a sharp and unforgiving focus. A series of policies by bewildered officials led to a “war” whose combatants would trudge out for a doughnut each morning without any indication of when they would be let off. The exhibit coolly notes that no one subjected to the control order programme was ever prosecuted.

Where the casual observer might simply see a number of artefacts from a period in history, Mr Clark’s artistic achievement is in arranging those artefacts with detached neutrality. From this askance viewpoint, the audience sees a nightmarish vision of a series of systems that, confronted with something they didn’t understand, resorted to process and absurdity. This may yet be the lasting image of the war on terror, in which, deprived of tangible violence, the combatants descended into a melee of pen-pushing.

"War of Terror" is showing at the Imperial War Museum, London until August 28th 2017