SAL PARADISE, hero of Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road”, carries only one book on his three-year travels across America. On a Greyhound bus to St Louis he produces a second-hand copy of “Le Grand Meaulnes”, stolen from a Hollywood stall. Entranced by the Arizona landscape, he decides not to read it after all.

Such is the fortune of Alain-Fournier’s story, one of France’s most popular novels, in the English-speaking world. Much loved yet little read, for almost a century this strange, earnest and inconsolable novel has haunted the fringes of fiction. Henry Miller venerated its hero; F. Scott Fitzgerald borrowed its title for “The Great Gatsby” (and some critics think Fournier’s main characters were models for Nick Carraway, Fitzgerald’s narrator, and his lovelorn pal). John Fowles claimed it informed everything he wrote. “I know it has many faults,” he sighed, as if trying to shake the obsession, “yet it has haunted me all my life.”

Despite its famous advocates, “Le Grand Meaulnes”—100 years old in 2013—is a masterpiece in peril. The stream of pilgrims who visit Fournier’s childhood home, near Bourges, is starting to thin. These days readers in Britain and America often choose denser, more overtly philosophical French authors. A decade ago, one British fan, Tobias Hill, noted that the book survived through “a barely audible system of Chinese whispers”.

Why are many English-speaking readers unfamiliar with a book adored by some of their most respected writers? And what accounts for the curious grip that this simply written and nostalgic tale of adolescent romance holds over its most besotted fans? Some love the poetry of its language, others the interlocking mysteries of its plot. Many are entranced by the elegiac sadness that rises from the prose, as one critic remarked, “like mist over the heath”. But its appeal partly lies in the romantic life and early death of its author, and the story of the woman who inspired him.

A brief encounter

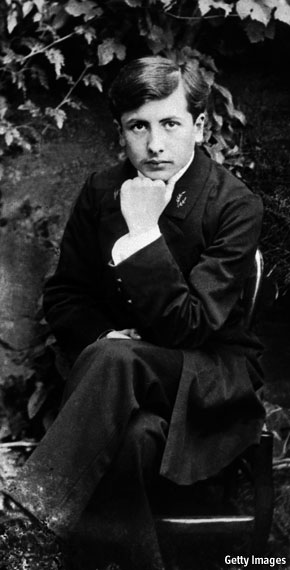

The life of Henri Fournier (pictured), now better known by his pen name, spun round a single, sunny afternoon in 1905, described in Robert Gibson’s valuable biography “The End of Youth”. Leaving an art exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris, when he was 18, he spotted a young woman walking with an older lady. Captivated, he followed them across the river to the door of a Left Bank apartment, afterwards returning to the building whenever his studies would allow. Too timid to knock, he paced the streets outside. Ten days later he saw the girl again—walking unaccompanied to mass—and approached her. Wary but flattered, she agreed to stroll with him by the Seine.

He told her he was a writer (or that he would be one day), the son of a country schoolmaster, now studying in Paris. She told him her name was Yvonne de Quiévrecourt, and that she was staying in the city with relatives, but leaving the next day. At her request they separated at the Pont des Invalides. Waiting where she left him, Fournier saw her look back twice. Years later he was still decoding this gesture: “Was it because, silently, from a distance, she wanted to reinforce her order that I should not follow her? Or was it to let me see her face one more time?”

Fournier clung to the memory long after it should have faded into his adolescence. He waited at the steps of the Grand Palais on the anniversary of his first glimpse of her (knowing, in rational moments, that she would not be there). He returned frequently to the apartment, hoping to spot her at a window. The word “She”, its first letter meaningfully capitalised, peppered his letters.

Other frustrations in his life helped this childish attachment foment into something powerful. He twice failed his university entrance exam, which kept him at school long after his peers had left. Mandatory military service prevented a third failure, but brought another two years of gloom. In 1909 he returned to Paris and moved in with his parents, plagued by “the feeling that youth is over and you haven’t done what you ought”.

Attempts to contact Yvonne brought Fournier further disappointment. In July 1907 he had finally called at the apartment building—to be told by the concierge that she had married the previous winter. Two years later, still disconsolate, he hired a private investigator. He learned her address, and that she had a child.

These discoveries distressed Fournier. Five years after the encounter he still labelled his fixation a “sickness”; occasionally his melancholy brought on bouts of real fever. But it also suited his nature to love at a distance. The memorable months he spent perfecting his English in Chiswick, in west London—where the young anglophile delighted in tea, jam and the landmarks made famous by his beloved Dickens—were marred only by the unsettling worldliness of British girls, who “get too friendly too soon”.

What is more, with Yvonne as his muse Fournier’s literary career gathered startling speed. His first published poems, all addressed or dedicated to the absent girl, earned him a job as a gossipy literary columnist for the Paris-Journal, which allowed him to befriend (and irritate) André Gide, Paul Claudel and other popular French writers. He founded an eccentric rugby club with the novelist Charles Péguy and Gaston Gallimard, a publisher. He briefly taught French to the young T.S. Eliot. In 1912 Fournier entered high society, becoming personal secretary and speechwriter to Claude Casimir-Périer, son of a former French president.

Love affairs arrived, eventually. He had a lengthy, tumultuous relationship with a milliner. An affair with a neighbour began when she dropped a note from her window onto the pavement in front of him. (It ended after her husband, sensing infidelity but uncertain of the culprit, vowed to murder his rival.)

Fantasy and reality

But none of these paramours could compare to Yvonne, whom Fournier had come to believe only the grandest gestures might win. By the end of 1912 he was carrying around a letter to the woman who had haunted him for seven years. “You left me only one way to rejoin you and communicate with you and that was to win literary fame,” it read. “A long novel which I’m finishing, a novel which is centred all around you—you whom I hardly knew—is coming out this winter.”

In truth Fournier’s literary ambitions were not born outside the Grand Palais—however fierce that singular thunderbolt—but forged years earlier in his father’s schoolhouse, where he and his sister would dog-ear the books bought as prizes for the best students. Still, “Le Grand Meaulnes”, which was published the following autumn, has Yvonne firmly at its heart.

In the novel, 17-year-old Augustin Meaulnes is sent to board at a country school. There he befriends François Seurel—the bookish son of the local schoolmaster and the novel’s narrator—and earns the admiration of his schoolmates, who bestow on him the title le grand. Months later Meaulnes stumbles upon a tumbledown chateau where a bizarre wedding party has assembled, its guests in lavish historical costume. There he encounters a beautiful young woman, but afterwards he finds it impossible to locate the strange estate, and the mysterious girl. Before his search comes to an end, a bungled suicide will leave one character disfigured; a brief affair in Paris will lead a young woman to the streets.

The story mixes fantasy and reality. Fournier’s childhood home among the moors and marshes of north-central France, to which he felt a morbid attachment almost equal to his longing for Yvonne, provides a nostalgic setting. The book features events and observations first chronicled in letters; a few passages quote directly from his correspondence. But its imagined elements, such as a circus troupe that vanishes overnight, recall the novels of Britain’s renowned adventure writers—Kipling, Stevenson, Wells and Defoe. An early chapter cites “Robinson Crusoe”.

Drawing the real and fantastical together is the meeting between Meaulnes and the elusive heroine, also called Yvonne. It is a faithful re-enactment of the encounter of 1905 that Fournier had recorded in his notebook. The novel sways between celebrating and condemning the obsessive and destructive search that follows; but Fournier was at least able to give his characters a concluding reunion—part wish-fulfilment, part tragedy—that his own story still lacked.

By 1913 he had reason to rid himself of his preoccupation, one way or another. In May he began an affair with Simone Casimir-Périer, a well-known actress and the wife of his employer. (Their relationship started in secret the night Fournier returned excitedly from the now-famous near-riot at the premiere of Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring”.) The letter he had drafted for Yvonne, still unsent, was intended to provoke a denouement. “I beseech you to take quite seriously these dreadful words,” he wrote. “I have no desire to live far from wherever you may be.”

As unlikely as it must have seemed to Fournier, it was mutual acquaintances, not tear-stained missives, that eventually connected them. Encouraged by her sister—who had heard, through friends, of Fournier’s infatuation—Yvonne herself arranged a meeting in Rochefort, on France’s west coast, in July 1913. The girl from the Grand Palais remembered many small details of their previous conversation. She admitted she had thought of it often.

Scribbled in his notebook are snippets of an exchange that must have saddened as much as delighted him. “If you had come three years ago,” she said to him, “everything might have been possible.” He gave her his love letter, but she promptly returned it, taking pains to show him that his imagined future was now inconceivable. She introduced him to her mother and her two small children. She invited him to visit them at home in Brest: “My husband will take you out into the country.”

From Rochefort to Verdun

Both parties hoped that the meeting in Rochefort would cure Fournier’s fixation. Back in Paris he admitted the clandestine trip to his lover Simone, prompting a bitter fight and passionate reconciliation that saw Fournier vow to forsake his adolescent obsession. Yet Yvonne continued to write to him. Fournier sent her copies of La Nouvelle Revue Française, in which “Le Grand Meaulnes” was then being serialised. She sent them back with annotations, which he assimilated into the final draft. In September 1913 she sent—and then swiftly retracted, through an intermediary—a more personal letter, the content of which is now lost.

That autumn Fournier bounced between two married women. Simone proclaimed her love for him but refused to leave her husband; Yvonne declared herself unobtainable but affected the reverse. A dilemma that would once have paralysed Fournier now made him decisive. In October he sent Yvonne an advance copy of the final, complete version of “Le Grand Meaulnes” (and a second for her husband). The dedication he scribbled inside—dated June 1st 1905 to October 25th 1913—was a celebration of his long infatuation with her, and also its memorial.

When war came the following summer, Simone agreed to divorce her husband and marry Fournier once the conflict was over. But privately Fournier did not expect to return from the battlefield. The deaths of many friends had already convinced him that his own life might be short. In 1912 a former schoolmate had overdosed on morphine. Another, refused permission to marry his fiancée, shot himself in the face at the age of 24.

Marching to the front, Fournier started to clean up his past. He asked Marguerite Audoux, a novelist and friend, to burn the two long letters he had written to her about his trip to Rochefort. He wrote to his sister to ask her to destroy his papers if he died, except for those concerning Simone. To her, he penned a more reassuring note: “Here’s to the happiness that awaits us and the children we shall have!”

During the early weeks of the first world war, before the trenches were dug, army lines were fluid and skirmishes frequent. On September 22nd 1914 Lieutenant Fournier led his company into woods south of Verdun. French soldiers patrolling nearby came upon a German field hospital; Fournier’s men joined the firefight that followed.

The few who escaped the battle could not say what had happened to the lieutenant. French authorities declared him dead, but his body was not recovered. For a month his mother, sister and lover sent increasingly desperate letters to the front. In 1918 they waited vainly for him to emerge, scrawny but alive, from some German camp. Later attempts to determine his fate returned grisly results. A German report—compiled in the 1920s but discovered decades afterwards—alleged that French survivors of the action had immediately been executed for attacking medical auxiliaries.

In 1991 researchers found his body, and those of his men, buried where they fell. The final photo of Henri Fournier is gruesome. Twenty-one skeletons lie in a shallow grave: two rows of ten, with one flung across the top. Fournier’s is in a corner, identifiable by its uniform. His skull has fallen to one side, his jaw is agape. He had been shot in the chest, suggesting he died in battle.

Missing in action

In the last year of his life Fournier had shaken off his daydreams. In death they defined him. In 1913 “Le Grand Meaulnes” had narrowly missed out on the Prix Goncourt—France’s most prestigious literary award—but the war propelled the novel to far greater fame. Many of those who had seen and survived the savagery appreciated Fournier’s elegy to innocence.

Most of his English-speaking readers come across the book at school, but he has become less well-known as languages, French in particular, have fallen out of fashion. Degree courses skip over the novel, perhaps because it doesn’t fit into any movement or genre. “It comes from nowhere and leads nowhere,” says Patrick McGuinness of Oxford University. “It is its own monument.”

Its ever-changing English titles do not help: “Big Meaulnes”, “The Great Meaulnes” and “The Magnificent Meaulnes” have all come and gone. Editions that omit the hero’s vowel-heavy name, such as “The Wanderer” and “The Lost Estate”, have had more success, though many publishers simply retain the French title. The author’s unusual pen name is another disadvantage. Alain-Fournier—an oddly hyphenated semi-pseudonym adopted to avoid confusion with a racing driver—was misspelled by an editor the first time Fournier used it, and is still often mangled.

Some think this creeping obscurity deserved, finding “Le Grand Meaulnes” mawkish and melodramatic, its plot contrived. Publishers play up the sentimentality with covers depicting pastoral scenes and teenage boys. That is a fair summary of the story’s first part, but a poor illustration of the oddness of the rest.

Yvonne de Quiévrecourt, the woman and the legend

Fowles, who called the book “the greatest novel of adolescence in European literature”, suggested that its detractors dislike being reminded of “qualities and emotions they have tried to eradicate from their own lives”. Fitzgerald camouflaged Fournier’s themes with a more sophisticated setting: Gatsby is no less juvenile than Meaulnes, but age and wealth make him seem more worldly. Happily, a small group of contemporary novelists still wear Fournier’s influence proudly. The young hero of “The Way I Found Her”, by Rose Tremain, acquires a copy of “Le Grand Meaulnes” from a Paris bouquiniste, who “looked quite miserable to part with it”. A mental patient in David Mitchell’s “Black Swan Green” relives the novel each day.

Critics have now puzzled out most of the book’s mysteries. The bleak final photo of Fournier solved his disappearance. The true identity of Yvonne de Quiévrecourt was revealed after her death. All the same, little is really known about the girl at the Grand Palais, who was both worshipped and artistically exploited by Fournier. She remained silent about her role in one of France’s most famous novels; by the end of her life she could not remember it herself. It fell to her husband to tell their children the story, as its fame grew around them.

In 1939 she apologised for not visiting Fournier’s sister, then guardian of his estate. “Far better for me to remain within the aura in which your brother enclosed me,” she wrote. Perhaps she was wise to stay as untouchable as the heroine she inspired. Probably no mere mortal could embody all the fascination and yearning that Fournier captures in “Le Grand Meaulnes”.