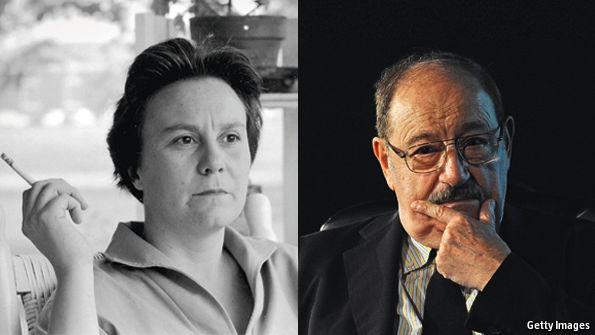

SHE was a plain, chubby, chain-smoking southern girl, living in a cold-water flat in New York and working as an airline-reservation clerk. He was a paunchy, balding, chain-smoking teacher of semiotics, the study of signs, codes and meanings in language, at various Italian universities. Both enjoyed producing small articles and pastiches, she for the college magazine, he for avant-garde publications, and it was only challenges from friends that induced either to embark on a novel. His first, “The Name of the Rose”, published in 1980, sold 10m copies worldwide. Her first, “To Kill a Mockingbird” (1960), sold more than 40m, and was proclaimed by some to be the best American novel of the 20th century. Umberto Eco rode literary stardom like a plump surfer on a giant laughing wave. Harper Lee was drowned by it.

“Mockingbird”, set in fictional Maycomb, Alabama, was a story of racial injustice seen through the clear but innocent eye of a small tomboy, Scout, whose father, Atticus Finch, was given the hopeless task of defending a black man accused of raping a white woman. On the eve of the civil-rights era the novel pricked America’s conscience, and reporters raced to photograph Miss Lee in her home town of Monroeville, Alabama, on the porch and in the courthouse, nervously smiling. The book was assumed to be her life in thin disguise. But in a rare interview in 1961 she said it was all fiction, nothing to do with her “dull” real childhood, and (unspoken but implied) would they please now go away.

Mr Eco would have queried that wished-for divide between fact and fiction. It wasn’t as clear-cut as that. The urge to tell stories, weave myths and simply lie lay deep in the possibilities of human language. But if facts could become fables, fables could lead to facts, just as wild medieval tales of lost kingdoms had inspired Europe’s exploration of America. Besides, any novel pretended to be true, and a good “open” text would spur the reader to judge and interpret that truth for himself. “Mockingbird” and “The Name of the Rose” were both essentially whodunnits, and “Who done it?” Mr Eco said, was the fundamental question of all philosophy.

His own journey through the labyrinth described an investigation by William of Baskerville and his sidekick, the novice Adso, into a series of gruesome murders in an unnamed abbey in the year 1327. He began with a pleasing idea, that a monk might be poisoned by reading a book, and took it from there, lovingly channelling the Middle Ages and pouring forth everything he knew. Again, though this was fiction, pages covered the theological, philosophical and scientific debates of the time, well-dosed (for those who knew) with his own semiotics in medieval dress.

Both he and Miss Lee dealt in sealed-off worlds: Maycomb isolated in cotton fields and quiet red dust; the abbey perched on precipices behind high walls. These were worlds in which rumours festered and conspiracy theories proliferated, fed by the feverish interpretation of signs. Both featured places (in the abbey, the library; in Maycomb, the tumbledown Boo Radley house) peopled by shadows and littered with symbols. In the abbey, painted phrases from the Apocalypse beckoned towards horror. In Maycomb, Indian-head pennies left in a tree seemed to do the same.

Despite her protests, Miss Lee’s minute evocation of Maycomb—the talcum scent of white women in the humid afternoons, the smell of Hoyt’s Cologne in the blacks’ church—was evidently drawn from childhood. And she had honed her skills of observation afterwards when Truman Capote, a childhood friend, took her along in 1959 to help with the exhaustive forensic interviews in Holcomb, Kansas that became “In Cold Blood”. Mr Eco, who worked from notebooks, index cards, obscure codices and hand-drawn maps, was seldom autobiographical, save for musing on the seductive symbols and myths of fascism with which he had grown up; and save for reflecting that his omnivorous curiosity, his love of lists and lunatic science (“Ptolemy, not Galileo”) and his analysis of every conceivable cultural artefact, from Thomas Mann to Mickey Mouse, from Snoopy to Avicenna, from TV quiz shows to the “Poetics” of Aristotle, had been fed in boyhood by reading Jules Verne.

Opening the text

Sudden fame encouraged him all the more. He travelled the globe, wrote columns for left-wing newspapers and produced six more novels: one, “Foucault’s Pendulum” (1988), about an all-encompassing conspiracy theory; another, “Baudolino” (2000), about webs of lies. All sold well. In his several residences he amassed a collection of 50,000 books; but he still spent five days a week merrily teaching semiotics in Bologna, partly at the university and partly, till late, in the tavernas of the town.

Harper Lee vanished. The second novel would not come, and she retreated to Monroeville. In 2015 the discarded part of “Mockingbird” was published as “Go Set a Watchman”, to tepid reviews. She too, in confused old age, was indifferent to it. But in Bologna one professor might have noted that “Watchman”, in which the noble Atticus suddenly expressed racist opinions, had opened up “Mockingbird” to new and startling interpretations: which surely should encourage the millions who loved it to read it all over again.