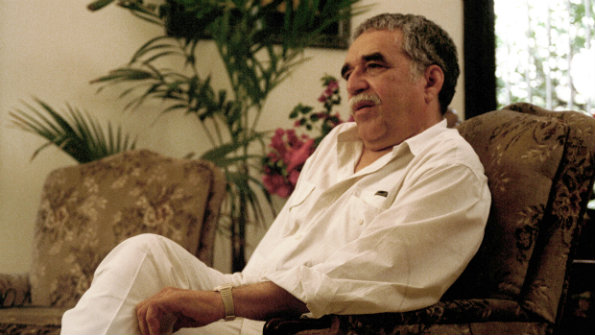

THE death of Gabriel García Márquez (see our earlier tribute) marks the passing of Latin America’s most popular novelist. He was not prolific—he wrote just six full-length novels—but in terms of world renown and sales Mr García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude” (1967) has eclipsed almost any other text translated from Spanish in the past 50 years.

In some respects this novel not only put its author’s native Colombia on the literary map but also his continent. “One Hundred Years of Solitude” came as a clarion cry from a culture from below the Tropic of Cancer celebrating its creation myths. It is really about nation-building, about a virgin world where things and creatures have to be given names. Mr García Márquez’s fiction reflects, as Mr Vargas Llosa has observed of Latin American writing in general, the region’s history of violent conquest, real events as fantastic as anything to be found in the wildest of novels.

It was in the early 1960s that Jorge Luis Borges in Buenos Aires began to be widely translated and it was he, along with the Chilean poet, Pablo Neruda, who flew the flag for literary South America in that era. Borges in particular was vital for the burgeoning novelistic career of Mr García Márquez. Having begun his writing career as a journalist, the Colombian always said he embarked on fiction surrounded by Borges’s books.

However, few of Borges’s great stories, written in the 1940s, presage the vibrant colours and landscapes in the Colombian’s narratives. The family-centred exuberance of “One Hundred Years of Solitude”, with its levitating priest and earth-eating orphan, or nearly 20 years later the ripe eroticism of “Love in the Time of Cholera” are markedly tropical.

Mr García Márquez is repeatedly called a chief proponent of “magic realism”. Borges is said to have invented it. But neither claim is quite true. Borges’s radicalism helped the younger novelist open up his own fictional territory, but the Argentine—who never wrote a novel—was more professorially locked into literature and how authors from all cultures interrelated, than concerned with strangeness and surrealism. His aesthetic was austere.

In contrast, Mr García Márquez brought a carnival abandon to storytelling, a Caribbean élan, and with these a great love for character and family epic: together they create a heightened realism. The “magic” in his novels, especially his most celebrated one, really consists of highly imaginative tricks. His narrative structures and chronological drive actually resemble those to be found in “Wuthering Heights”—not a bad book to model yourself on, whatever tradition you are writing from. Emily Brontë's extraordinary mid-19th-century saga is partly about what humans cannot escape from, their family and biological “code”. “One Hundred Years of Solitude” is also a drama of genealogy, relishing the successive patterns of desire and frailty passing through a single family.

Mr García Márquez was certainly new, though. And his crowning achievement remains the way his most adored novel alerted the wider world to a literary culture that few outside a small group of struggling southern nations knew much about.