THE stone lions that guard the Romanesque cathedral at Modena, in northern Italy, were doubly dear to Dario Fo. As a lover of medieval architecture, he studied and revered the old beasts as art. But after roughly 2,000 years of roaring their noses were worn away, their teeth gappy and their expressions dimly surprised. These symbols of the combined might of church and state had been taken over by the people—usually small people, who rode on them laughing and kicked their curled manes with vicious little feet.

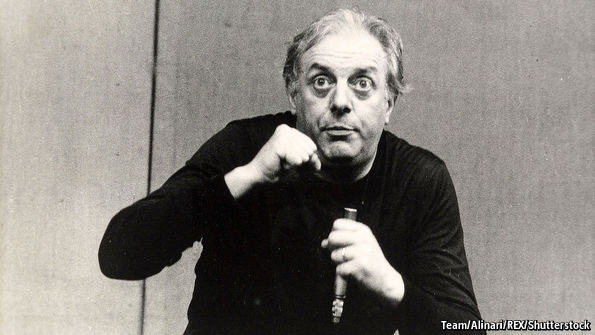

All Mr Fo’s life in theatre and politics (the one infusing the other all the time) was dedicated to the idea of il popolo contro i potenti, the people against the powerful. He put himself squarely in the tradition of the giullari, the mocking, singing jesters of medieval Italy, who kept on the move because they were liable to be hanged if they stayed still. The work that made his name and notoriety, “Mistero Buffo” (“Comedy-Mystery”), was a one-man show in which, his long limbs feline in a black jumper and grey trousers, he told, mimed, sang and shouted New Testament stories like an idiot. His Jesus got drunk at the marriage at Cana, climbed on a table and exhorted everyone to forget the afterlife for the here and now; his raising of Lazarus was recounted by a furious pickpocket victim in the crowd. The line to the medieval mystery plays was direct. When Mr Fo won the Nobel prize in 1997 he received it on behalf of all mummers, tumblers and clowns.

Ordinary people were the heroes of all his plays, or rather farces, and authorities of every sort his villains. This touched a raw nerve in the chaotic, kidnap-and-inflation-ridden Italy of the mid-20th century, but also far outside it. His most famous play, “The Accidental Death of an Anarchist” (1970), concerned the true, mysterious defenestration of an activist while in the hands of the police. His second-most-famous, “Can’t Pay? Won’t Pay!” (1974), starred two housewives driven to shoplifting by extortionate food prices. Both manic comedies were built up from outrage that made the laughter stick in your throat. Which was more dangerous, an innocent anarchist or a corrupt judicial system? Which was the greater crime, stuffing a jar of olives under your coat, or charging more than workers could possibly afford?

He wrote as people spoke, with plenty of swearing, obscenity, Lombardy dialect, tall tales from smugglers and fishermen and the invented language, “grammelot”, he picked up from foreign workers in a glass factory near Lake Maggiore, where he grew up as a stationmaster’s son. His favourite local story mocked docile villagers on the Rock of Caldé who, even as the village and its church bells were sinking underwater (“Dong…ding…dop…plock…”), insisted they weren’t drowning.

Riots and risotto

Having written “lines to chew on” (in a few days, usually), and made the

sets, costumes and masks, all in devoted partnership with his actress wife,

Franca Rame, he would take his shows direct to the people. Early on he played

regular theatres, but these were too cosily bourgeois. He sought “solidarity

with the humble” in union halls, prisons, factories or park pavilions, places

with bad acoustics but great for debate. La Comune, his theatre group, threw

out the “fourth wall”, letting the audience mill onstage with their own

interventi about rotten mayors, magistrates, bosses and the criminal

state. They had plenty.

The authorities raved at him. His plays were cut, thrown out, closed down; he was briefly arrested and frequently put on trial, though always rising up victorious. The Vatican declared “Mistero Buffo” to be the greatest blasphemy in the history of television. He was banned for 14 years from RAI, the state broadcaster, for proposing in 1962 a play in which factory bosses refused to shut down production after a visitor had fallen into the meat-grinder, preferring to turn out instead another 150 tins of mince.

Like any jester, though, he couldn’t be kept down—not with Silvio Berlusconi’s bunga bunga around, or global financial collapse. (He dreamed that, after a double assassination attempt on Mr Berlusconi and Vladimir Putin, Italy’s then-prime minister was saved with a transplant of part of Mr Putin’s brain.) He was not a formal communist and, when he ran for mayor of Milan in 2005, seemed unsure which party he was in. But apparent chaos almost always masked careful preparation. “Accidental Death” took months of rigorous legal research. On a typically mad day in his flat, with the phone ringing off the hook and people rushing in and out, farce-like, he (and she) could still perfect the moves for his latest piece over Franca’s sublime risotto milanese.

As if all that were not enough, he directed operas too; and painted. He had loved painting all his life, and thought it the highest form of art he attempted. It wasn’t pure, of course. Politics polluted that, too. And indeed it had to, if art was to have any use in its own time. His beloved cathedral of Modena had been built by simple, exploited workers like those who came to his shows. But if he himself had carved those guardian lions, they would have held in their teeth the greasy remains of a howling politician or a squealing, mangled judge.