“THERE’S this poet from Canada…He plays pretty good guitar, and he’s a wonderful songwriter, but he doesn’t read music, and he’s sort of very strange.” It was an unconventional pitch from a manager hoping to attract the attention of John Hammond, one of the most influential record producers around. But Mr Hammond was intrigued, and decided to invite the poet to lunch. Once they had eaten, the young Leonard Cohen sat down to play a dozen of his tunes. Mr Hammond was hooked: “You’ve got it, Leonard”.

Within a week Mr Cohen was working on his first album and some of his finest songs, “Sisters of Mercy”, “Suzanne” and “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye” in the studios of Columbia Records. It was 1967, and he was in his 30s. Back in college he was in a folk band with a couple of guys: they wore Buckskin jackets and played their biggest gigs in church basements and school halls. But most of the years since had been spent chasing his ambitions as a poet, writing books fuelled by drugs and making love on an idyllic island in Greece. This did not pay the bills, however, and when the release of his second book “Beautiful Losers” came under fire for having “obscure” sexual content, Mr Cohen decided it was time to look elsewhere. He set off to Nashville and on the way found himself captivated by the scene in New York.

He saw music as his second calling, and rightly so. His words were all the more beautiful put to sound. After 14 albums and a career that spanned into his 80s, Mr Cohen remained unique in his ability to produce songs that could consume the listener, envelop them in darkness and reflection, and offer great comfort and hope all the while. He articulated like no other the universal unease and helplessness felt by society in a changing world. Some, like “If it be your will”, are more akin to prayer than song; others see Mr Cohen having fun, gently mocking those who praise him: “I was born like this, I had no choice, I was born with the gift of a golden voice.”

Despite “Hallelujah” going on to become one of the most widely-covered songs in history, some felt that the weight of his songs may have prevented him from reaching the same commercial success enjoyed by that of his contemporary Bob Dylan, among others. Mr Cohen built up a loyal fan base and widespread appreciation for his transfixing lyrics and painstaking craftsmanship (it took him years to write a single song, a process he described as “like a bear stumbling into a beehive or a honey cache”). Even as Mr Dylan received the Nobel prize for literature, many wondered whether Mr Cohen would have been a more deserving candidate.

On stage, few artists could inspire an audience to weep, to console and to laugh like he did. During his first major tour back in 1972, Mr Cohen implored the audience to stop applauding: he was too nervous, too distracted, and he couldn’t go on singing. When he returned to the stage to sing “So Long, Marianne”, based on former girlfriend and muse Marianne Ihlem, the audience joined in and Mr Cohen and his band were reduced to tears. Backstage and broken, he noted how overwhelming the experience had been.

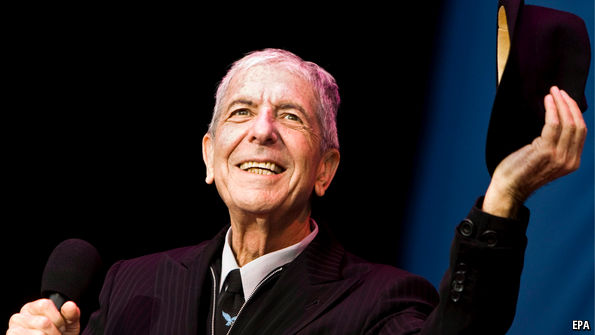

In the twilight of his life, the conflicted states of mind and nerves that plagued every show of his youth seemed to all but disappear. Forced back on the road after his manager, Kelley Lynch, left him financially broke, Mr Cohen truly came into his own playing three and a half hour sets, right up to each venue’s curfew. In the opening pages of her biography on him, Sylvie Simmons describes Mr Cohen as “a courtly man, elegant, with old-world manners”. Anyone who saw him live knows that to be true. Surrounded by his band, sharing anecdotes and thanks, Mr Cohen electrified the audience with a charm and wit so at odds with the “godfather of gloom” reputation bestowed upon him.

His death last week was met with deep sadness and countless tributes; some, like Kate McKinnon’s heartfelt performance on SNL, a fitting end to a tumultuous few days. Only a month before, Mr Cohen released what was to be his last album, “You Want It Darker”, to critical acclaim. The opening track sees Mr Cohen proclaim “Hineni, hineni, I’m ready, my lord”: it seemed prophetic then, and even more so now. The world may not be ready for his absence, but solace can be found in the body of work he took great care to leave behind.