John Gray

Being Human

At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being and Apricot Cocktails

By Sarah Bakewell

In 1962, Martin Heidegger went on a cruise to the Aegean. Going to Greece

had not been an easy decision. Seven years earlier he had got so far as to

buy train and boat tickets; when the enormity of what he was attempting dawned

on him, he cancelled the trip. He tried again in 1960, and once more called

the trip off. Visiting the homeland of the oracular pre-Socratics and the

only truly ‘philosophical’ language apart from German was too much of a

risk. When he finally screwed up the courage to take the cruise, he hated

the country he found. With Olympia now a mass of ‘hotels for the American

tourists’, the ancient site no longer ‘set free the Greek element of the

land, of its sea and its sky’. When the boat reached Crete and Rhodes, he

stayed on board reading Heraclitus.

Sarah Bakewell’s witty account of Heidegger’s journey recalls the philosopher

Sidney Morgenbesser’s response to the Heideggerian question, ‘Why is there

something rather than nothing?’ ‘Even if there had been nothing,’ Morgenbesser

is supposed to have quipped, ‘he’d still not be satisfied.’ Heidegger was

a central figure in generating the loosely defined current of thought commonly

known as existentialism. His own thought was in many ways derivative, but

he never allowed a debt – intellectual or personal – to stand in the way

of his own advancement. He owed his academic career to Edmund Husserl, who

more than anyone else originated existentialist thinking with his call for

the direct study of human experience – phenomenology – to be accepted as

the foundation of philosophy, and whose chair at the University of Freiburg

Heidegger inherited. But Heidegger did nothing to assist his mentor in 1933

when Husserl was prevented from using university facilities under Nazi laws

requiring the dismissal of Jewish academics, failed to attend Husserl’s

funeral in 1938 and removed the dedication to Husserl in the 1941 edition

of Being and Time. An enormous literature exists on Heidegger’s relations

with Nazism, but Sartre captured an essential part of that involvement when

he wrote in an essay of 1944: ‘Heidegger has no character; there’s the truth

of the matter.’ As a human being, Heidegger was less than nothing.

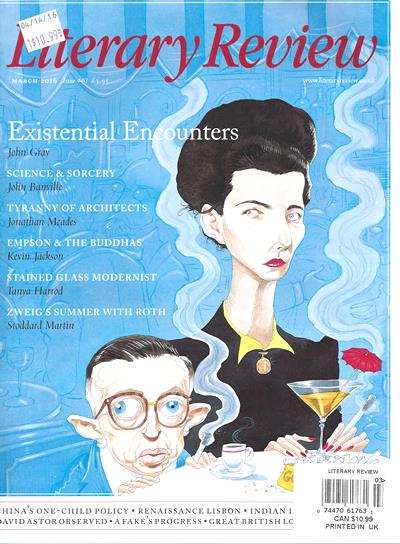

Author of an inspiriting life of Montaigne, Bakewell clearly likes writing

about thinkers for whom she can feel admiration and affection. To her credit,

she does not flinch from recording Heidegger’s squalid manoeuvrings during

the Nazi period and his unending evasions thereafter. She does a good job

tracing Heidegger’s influence on the French thinkers who turned phenomenology

into something like an intellectual movement, the inception of which she

dates to a conversation near the end of 1932, in the Bec-de-Gaz bar on rue

Montparnasse in Paris, between Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and

Sartre’s old school friend and later political opponent Raymond Aron, who

had been studying in Berlin. Aron described the phenomenological philosophy

he had encountered in Germany: ‘if you are a phenomenologist, you can talk

about this cocktail and make philosophy out of it!’ De Beauvoir wrote later

that on hearing this Sartre turned pale with excitement. She and Sartre had

tried to read Heidegger’s lecture ‘What is Metaphysics?’ when it appeared

in French in 1931, but ‘could not understand a word of it’. Now they saw

the point: Heidegger was founding a type of philosophy that set aside traditional

concerns with metaphysics and the theory of knowledge in order to examine

the givens of immediate experience, whatever they might be. Aided by their

friend Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who had attended lectures given by Husserl

in Paris, they resolved to promote this new philosophy in France.

In fact, Heidegger wasn’t doing anything new. The Russian-Jewish fideist

Lev Shestov (1866–1938), one of the most interesting thinkers in the history

of existentialism (though not mentioned by Bakewell), recorded that when

he met Heidegger in Husserl’s home in 1928, Husserl was insisting on the

importance of reading Søren Kierkegaard, the heterodox Danish theologian.

Heidegger had already taken the hint. As Shestov later noted, Being and

Time was not much more than a translation of Kierkegaard’s ideas into

Husserlian categories, with religious conceptions of the fall of man reappearing

as hermetic Heideggerian notions such as ‘thrownness’. An indeterminate religiosity

pervades much existentialist writing. In some cases – Shestov and Simone

Weil, the Catholic thinker Gabriel Marcel and the later work of Emmanuel

Levinas, for example – the influence of religion is explicit. But religious

ideas are present in Sartre’s work as well.

Citing a conversation with de Beauvoir in which Sartre declared that

they should work on ‘a great atheist, a truly atheist philosophy’, Bakewell

writes that she is ‘more impressed now than ever by Sartre’s radical atheism,

so different to that professed by Heidegger, who abandoned his faith only

in order to pursue a more intense form of mysticism. Sartre was a profound

atheist, and a humanist to his bones.’ Yet Sartre’s atheism featured a conception

of human action whose origins in theism are unmistakable. As Bakewell notes,

one of the central tenets of existentialist thinking – especially Sartre’s

– is the belief that ‘human existence [is] different from the kind of being

other things have. Other entities are what they are, but as a human I am

whatever I choose to make of myself at every moment. I am free.’ Anyone who

thought of their lives as being in some way ruled by fate was guilty of

the cardinal existentialist sin of inauthenticity – the denial of one’s own

freedom. But where does this idea of freedom come from? Not from the ancient

Greeks or Romans, or from modern science. Plainly, it is a secular version

of the theistic faith in free will. Like much else in 20th-century thought,

Sartre’s existentialism was largely spilt religion.

In Sartre’s case, existentialism was also an intensely political engagement.

Bakewell recounts the philosopher’s convoluted interactions with the French

Communist Party – a dreary tale of self-deception, spotted with elements

of black comedy. It’s a pity she doesn’t explore the episode described in

Carole Seymour-Jones’s A Dangerous Liaison: Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul

Sartre (2008), in which, during a visit to Moscow in 1962, Sartre became

involved in a relationship with a KGB agent. As the agent, Lena Zonina,

wrote in a report at the time, the philosopher’s visit was ‘set up in such

a way as to give him a complete illusion that he meets with anyone he wants

to meet, that he chooses the subjects for conversation, and that he works

out his own programme rather than follows one imposed on him’. Sartre was

taken in by the deception, falling in love with Zonina, an attractive and

highly intelligent but ailing and vulnerable woman who was herself acting

under severe constraint, proposing marriage to her and visiting the Soviet

Union on no fewer than eight occasions within four years in order to be with

her. With Sartre unwilling to make a decisive break with de Beauvoir and

the philosopher’s usefulness to the Soviet cause waning, the relationship

came to an end. But the carefully engineered romance seems to have served

its purpose in bolstering Sartre’s belief that communism ‘must be judged

by its intentions and not its actions’.

Towards the end of this absorbing and enjoyable book, Bakewell writes:

‘Ideas are interesting, but people are vastly more so.’ She presents a cast

of characters who are undeniably diverting. Simone de Beauvoir, in particular,

emerges as a highly complex individual, far more interesting than her egotistical

and gullible partner. Karl Jaspers, frail in health but resolute in his determination

to remain untainted by Nazism; Emmanuel Levinas, who withstood Nazi oppression

and clearly perceived Heidegger’s culpability; Albert Camus, much given

to high-flown rhetoric but with a sense of reality that kept him from Sartre’s

political follies: these were substantial figures. But most of the existentialists

were not particularly distinctive either in their ideas or as human beings.

The ineffably bourgeois Merleau-Ponty, extolling the virtues of ‘proletarian

humanism’ and the necessity of communist terror, was representative of many

of them – a bog-standard mid-20th-century French bien pensant. For

all their talk of authenticity, those who are best known for shaping existentialist

thinking were notable for embodying the fashionable attitudes of their

time.