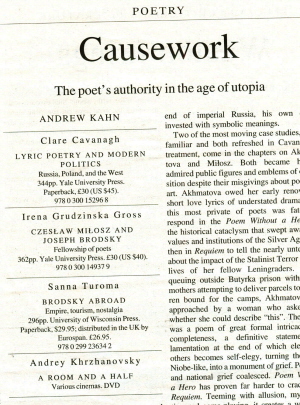

Causework

The poet's

authority in the age of utopia

ANDREW KAHN

Clare

Cavanagh

LYRIC POETRY

AND MODERN POLITICS

Russia,

Poland, and the West; 344pp. Yale University Press.

*

Irena

Grudzinska Gross

CZESLA W

MILOSZ AND JOSEPH BRODSKY Fellowship of poets

362pp. Yale

University Press. £30 (US $40). 9780300149379

*

Sanna Turoma

BRODSKY

ABROAD

Empire,

tourism, nostalgia 296pp. University of Wisconsin Press.

Paperback,

$29.95; distributed in the UK by Eurospan. £26.95.

978 0 299

23634 2

*

Andrey

Khrzhanovsky

A ROOM AND A

HALF

Various

cinemas. DVD

What becomes

of lyric poets who put their "service to the muse", as Pushkin called

it, to the service of their nation? Can political poetry couched in

lyric form

ever be truly transnational? Can poets even in exile ever escape the

mental map

of their native land? These are the questions addressed by three new

books and,

less directly, represented in Andrey Khrzhanovsky's film about Joseph

Brodsky, A Room and a Half. All make serious

attempts to consider the relation of the art of poetry to the lives of

poets.

Clare Cavanagh and Irena Grudzinska Gross substantiate the view,

criticized

elsewhere, that in twentieth century Soviet Russia and Poland the

impact of

lyric poetry has been national because these cultures in their

different ways

bestowed a special authority on poets - sometimes to their great

personal cost.

Recent micro-histories of the literary politics, institutions and

aesthetic

ideology of Soviet-era culture have shown that even while orchestrating

pervasive control over the general population, the state apparatus

subjected

writers to particularly close scrutiny, often at the level of the

Politburo and

Party leader himself. Poets such as Vladimir Mayakovsky and Boris

Pasternak,

who initially welcomed a revolutionary utopia, or those who kept their

own

counsel such as Anna Akhmatova, learnt by the end of the 1920s that

their

standing with the regime, and their chances of survival, fluctuated on

a

text-by-text and sometimes line-by-line basis as the "Revolution from

Above" ordained style and content. The impact on their creative

psychology

was immense.

Of course,

this plight does not automatically confer distinction (and Cavanagh

acknowledges the challenge to glib equations that Geoffrey Hill poses

in his

essay "Language, Suffering and Silence"). However, the poets

assembled in Lyric Poetry and Modem

Politics combined exceptional talent with outstanding charisma.

Under the

pressure of circumstance and compelled by conviction the Russians

Alexander

Blok, Akhmatova, Mayakovsky and Osip Mandelstam, and the Poles Wislawa

Szymborska, Stanislaw Baranczak, Zbigniew Herbert and Czeslaw Milosz

attuned

their lyric voices to a civic message. Armed with a mastery of both

Russian and

Polish scholarship and a bracing style of argument, Cavanagh's

important and enthralling

book illuminates the creative biographies and works of writers who from

about

1917 to the dissolution of the Soviet bloc experienced, documented,

tested, challenged

and sometimes survived the confrontation with the State - or perished

when

speaking up for themselves and others.

Of the three

authors reviewed here, Cavannagh is the most sophisticated commentator

on the

uses of biography and also the most subtle reader of lyric. Her point

of

departure is the concept of "life-creation" (zhiznetvorchestvo),

the conflation of art in life and life in art

observed pervasively in Russian modernism. In chapters on Blok,

Akhmatova and

Mayakovsky, she explores how poets accustomed to self-portrayal on an

intimate

scale acquired a different sense of purpose and adjusted their artistic

means.

A systematic comparison of Blok and W. B. Yeats shows how each, in

response to

an analogous set of personal and national concerns, wrote poems and

projected

lives that mirrored one another. Each was gripped by the force of

history in

their own countries, mesmerized by the occult, enraptured by mystical

embodiments of female wisdom. Whereas Yeats moved beyond his symbolic

masks to

advance socially, father a family and become bard to a national revival

in

Ireland, the childless Blok thrilled to the end of imperial Russia, his

own

death invested with symbolic meanings.

Two of the

most moving case studies, both familiar and both refreshed in

Cavanagh's

treatment, come in the chapters on Akhmatova and Milosz. Both became

highly

admired public figures and emblems of opposition despite their

misgivings about

political art. Akhmatova owed her early renown to short love lyrics of

understated drama. Yet this most private of poets was fated to respond

in the Poem Without a Hero to the historical

cataclysm that swept away the values and institutions of the Silver

Age, and

then in Requiem to tell the nearly

untellable about the impact of the Stalinist Terror on the lives of her

fellow

Leningraders. While queuing outside Butyrka prison with other mothers

attempting to deliver parcels to children bound for the camps,

Akhmatova was

approached by a woman who asked her whether she could describe

"this". The result was a poem of great formal intricacy and

completeness, a definitive statement of lamentation at the end of which

elegy

for others becomes self-elegy, turning the poet, Niobe-like, into a

monument of

grief. Personal and national grief coalesced. Poem Without

a Hero has proven far harder to crack than Requiem.

Teeming with allusion, mystification

and game-playing, it creates a world of distorting mirrors in which

life and

art collide, identities and masks are skewed; a bravura modernist

performance

whose openness thwarts single interpretations, it remains a more

private vision

of an epoch remembered in highly personal symbolic terms. Different

forms, as

Cavanagh shows, convey the tension between answering the vocation of

the bard

and preserving intact the intimate, mysterious self that is a source of

lyric

poetry. Akhmatova's solution to the public/private dilemma proved to be

unavailable to Mayakovski, a titan of revolutionary rhetoric who was

ultimately

trapped by the political script he made for himself. Mayakovski equated

his

personal feeling with the state of the nation. Like Whitman, the great

model of

t democratic poet as man of the nation a bard, he cast himself as the

force for

change. As long as Mayakovsky spoke the Revolution and the Revolution

spoke

Mayakovsky the colossal egotism of his poetry found a truly national

scale. The

organic bond between his utopian enthusiasm and the Revolution was

sundered as

the country departs from his ideal (and proletarian write] groups

marginalized

him). Lenin never liked Mayakovsky, and the next generation leaders

expected a

spokesman rather than prophet. The betrayal of the Socialist utopia led

to his

suicide, an act that was itself wide regarded as a betrayal. In a

fascinating

chapter, Cavanagh shows how Mayakovsky’s biographer, the Polish poet

and critic

Wiktor Woroszylski, long gripped by his youthful commitment to

Mayakovsky as an

insurrectionary ideal, sidestepped the question of his suicide by

compiling his

massive biography out of a collage of quotations. Eventually as his own

disillusion with Soviet rule increased, his resistance to the truth of

Maykovsky's

tragedy ebbed away.

In a later

chapter entitled "Counterrevolution in Poetic Language: Poland's

generation of '68", Cavanagh aims jibes at literary theory, especially

Deconstruction. Her argument that the rebel students of 1968 were the

shock

troops of Tel Quel, though not historically convincing (Richard Wolin's

recent

book The Wind From the East treats the

true cluster of causes), nevertheless acts as a rhetorical foil to the

powerful

case she makes showing how lyric poems opened the eyes of individuals

to the

anti-individualistic and anonymous values of the State. Together with

some

reservations about New Historicism, her criticisms make a secondary

argument

about the value of lyric poetry in sensitizing perception to detail and

specificity, and in sharpening our sense of individual agency and

responsibility (a sense that cannot easily be explained away with

reference to

systems like the literary field or code).

The expense

of spirit brought about by compromises with power, compromise lyric

talent, has

different measures. Both Szymborska and Milosz tried to persuade

themselves to

believe in a utopian future at the end of the Second World War.

Szymboska joined

the Party, and Milosz embarked c a diplomatic career that he ended in

Washington

in 1951. The accounts of both Cavanagh and Gross convey how these

decisions continued

decades later to influence reaction home among unforgiving, often

nation

segments of their readership (as well as the happier story of Milosz's

remarkable impact on American poetry). In his ABC,

Milosz described his own life story as astonishing but likened

that of Joseph Brodsky to a morality tale: "he was tossing manure with

a pitchfork

on a state farm near Arkhangelsk, then, just a few years later, he

collected

all sorts of honors, including the Nobel Prize". Drawing on personal

papers and her own memories, Gross's double portrait in Czeslaw Milosz

and

Joseph Brodsky is at its best when describing the inextricable

connection

between creative personality and a sense of exile. She reproduces at

length a remarkable

letter from Milosz written to Brodsky shortly after his arrival in the

United

States, offering consolation with an unvarnished and unglamorous view

of the

difficulties of adjustment. If life simply replayed myths then a young

poet

steeped in Dante, Ovid, Byron and Pushkin might have felt confident

about his

eventual destiny, but Milosz understood the huge anxiety about

survival, both practical

and intellectual, that Brodsky experienced. Brodsky had suffered his

first

heart attack at the age of twenty-five, and while his nervousness

(mentioned by

his friend Tomas Venclova in a foreword to Gross's book) disappears

from the

portrait offered in Khrzhanovsky's film, A

Room and a Half, it animates his writings about travel and

landscapes

discussed by Sanna Turoma in Brodsky

Abroad.

Khrzhanovsky's

biopic has the post-Soviet Brodsky recalling his younger self. The film

is

worth seeing for the excellence of the acting, and for its ingenious

splicing

of documentary footage of Brodsky himself and the actors impersonating

him. As

a portrait, it is at its best when it stays close to its main source,

Brodsky's

wonderful essay "In a Room and a Half' (1985), whose title refers to

the

sum total of space allocated to Brodsky and his parents in their

communal flat

in Leningrad. Brodsky's double portrait of his family and city is a

masterpiece

of filial tribute and, quite surprisingly, sociological analysis as it

recounts

the impact of all sorts of restrictions (physical, verbal, sexual) on

the

yearning of an adolescent to be free and self-determining. The film

conveys

these feelings in its scenes from the 1960s where poetry and the

Beatles vie

for hearts. As for the Muse, Brodsky was a lover of cats as well as

women, and

Khrzhanovsky, a celebrated animator, diverts the question of

inspiration into a

series of cartoonish intercuts featuring a feline alter ago purring

with poetic

energy.

In Brodsky

Abroad, the author travels, but

the discourses of postmodernism and postcolonial theory do much of the

talking.

Here biography, circumstance and context matter only marginally. The

bias

towards theory (the discourses of the "exilic" and tourism) sharpens

Turoma's argument, but robs it of a dimension of complexity.

Affiliating

Brodsky with a gallery of anonymous cosmopolitan travelers

underestimates the

strong counterpoint of autobiography in his prose (rather more than his

poetry). Reducing his verbal mannerisms to a mere reflex of the genre,

combining the associative patter of Sterne with the meta-textual ploys

of Italo

Calvino's If on a Winter's Night a Traveler, misses the fact that

Brodsky's

prose generally makes a feature of false starts and self-consciousness.

He

liked reticence. Yet like the Calvino of Invisible

Cities - highly popular at the time - some of the most textured and

impressionistic writing such as Watermark,

Brodsky's long essay on Venice, hovers between the inner landscapes

superimposed by memory on new vistas and the sheer disorientation of

travel.

The physical resemblance between the waterways of Venice and St

Petersburg, and

the relation of sky and building elicits memories of the Leningrad he

never

revisited, collapsing past and present. Brodsky focalized the

interchange of

impressions through photographic and cinematic techniques, media whose

influence Turoma rightly notes.

As an exiled

son of the Soviet empire and adopted son of the American empire,

Brodsky was

obsessed with the political, physical and metaphysical limits of

empire.

Whether the Occidental-Oriental division examined by Turoma correlates

to a

pattern of appreciation and denigration driven by "Euro-imperial"

values

should occasion debate. Brodsky's passion for Venice and St Petersburg

was inseparable

from the classical as an aesthetic benchmark. The absence of classical

antiquity conditions his coolness to Rio de Janeiro and his sense of

being

overwhelmed in Istanbul. This reaction has been cast as a belated,

Orientalist

fantasy of the white male traveler hankering for domination. Just where

- and

indeed whether - Brodsky crosses the line from purely aesthetic

prejudice to

xenophobia or Islamophobia remains hard to tell. When seen from the

perspective

of

postcolonial ideology, matters of taste will always seem to reflect

underlying

cultural suppositions and power structures. Turoma's attention is

understandably drawn to Brodsky’s provocative and politically incorrect

"The Flight from Byzantium" (1985), an essay in forty-five sometimes

discontinuous sections that meditates on the connections between

history and

geography, and while elegizing classical antiquity controversially

discusses

the "dusty catastrophe of Asia". Her analysis is welcome, but does

not tell the whole or only story. That Brodsky loved the Roman, and

that he

even at times wrote as though he were a Roman, is obviously true. But

many of

his classicizing poems cast beauty in terms of decay and apocalyptic

decline,

and find tyranny and fascism lurking behind well-regimented beauty. By

the same

token, sometimes his travel experiences look less loaded with meaning

and more

innocent. "After a Journey", an account of his trip to Brazil for a

conference in 1978, describes a series of mishaps more belittling to

the poet

than aggrandizing. Keen to explore Rio, Brodsky has his pocket picked.

With no

cash and stuck at the conference, he finds the view from the balcony

circumscribes his horizons. The postcolonial script associates the

motif of the

balcony with the "master of all he surveys" trope. But in this case

the poet is hardly master of anything and the passage affords the

reader a

chance to take a snapshot of a comically worried subject who, as it

happens,

was photographed on the balcony by his father annually in childhood (a

ritual

that features in the film A Room and a

Half). Travel has hardly taken the boy out of the man.

More

biographical emphasis might have unlocked the complications of "Flight

from Byzantium". Gross's discussion provides a complementary

perspective.

What Turoma analyses as the theme of Russian cultural superiority also

looks

like the defensive reflex of a figure caught between a demanding émigré

community and a vociferously liberal New York intellectual scene that

repeatedly

put him on the spot. Russophilia and

Soviet

phobia cohabit uneasily. At times, the pressure to defend the legacy of

Russian

culture, rather than the State, sparked a Dostoevskian reflex to goad

liberals

(among them, some of his best American friends) by sounding staunchly

pro-American in defiance of their criticisms of his adopted land.

Just how much

the Cold War rivalry galvanized young minds in the 1980s may now seem a

distant

memory. Milosz and Brodsky were omnipresent authorities on the writers

of

Russia and Central Europe (a term Brodsky disliked, as Gross reminds

us) who

had disappeared into the totalitarian pulping machine. Literature

seemed a live

wire to political change, a means of liberation with the decline of the

Soviet

Union, and cause for scholarly devotion. The phenomenon described in

Cavanagh's

book played out over decades. She sees a gruesome irony in the fact

that while

Roland Barthes was proclaiming the Death of the Author, real-life

authors were

suffering and dying in the Eastern Bloc. Yet forcing the dichotomy is

problematic

because Barthes wished to liberate criticism from the dead hand of

biographical

positivism. Many recent Polish poets - Szymmborska, Baranczak, Herbert

in

particular have used a rhetoric of irony and ambiguity similar to

techniques of

Deconstruction, and in the aftermath of perestroika Russian

intellectuals

flocked to French theory.

If the case

for teaching literature rests partly on its moral gravitas and social

message,

and frankly Romantic acceptance of genius, the time might be ripe to

ponder the

decline of literary prestige as a point on which East and West have

converged

since the end of the Cold War. I recall how in 1991, a Moscow

conference marking

the centennial of Mandelstam attracted many hundreds of poetry lovers

as well

as academics. When a young speaker misremembered a line from one of his

lesser-known poems, virtually the entire auditorium erupted into a

spontaneous

correction. Nowadays there is no problem finding an edition of

Mandelstam's

works, and thankfully the death of the author looks a purely private

matter. But

a pool of acolytes, drawn from both the intelligentsia and the wider

public,

scarcely exists. The fervor and commitment of a mass of people

dedicated to

poetry and moved to action by its structures and messages of

intellectual

freedom now seem historically unique.