|

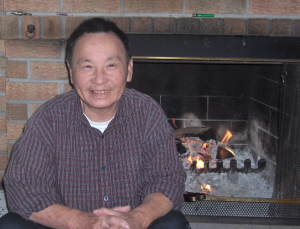

Karl Schlagel

REVOLUTION ON MY MIND: WRITING A DIARY UNDER STALIN

by Jochen Hellbeck.

Harvard, 436 pp., £19.95, May

2006,9780674021747

Note:

Hôm qua vào tiệm sách ngày

boxing day thấy quyển Les

Chuchoteurs của Orlando Figes - định

mua tặng bác làm quà Noel nhưng thấy số trang : 800 thì dội lui, bác

còn thì

giờ đâu mà đọc, sách lại in chữ nhỏ.

Thiệt là buồn khi đọc băng in

rời ngoài quyển sách lời của Emmanuel Carrère : Quyển sách này thật

hay, Figes

đặt tên lại cho người chết, cho người bị xóa tên. Đối với chúng ta đó

là những

câu chuyện, nhưng với họ, đó là cả cuộc đời.

Avec ce livre magnifique,

Figes redonne un nom aux morts, aux effacés de la mémoire. Pour nous ce

sont

des histoires, eux c’était leur vie.

*

Tính thẩy tờ London Review of Books,

16 Tháng Tám, 2007 [đúng sinh

nhật Gấu, tếu thế!], vô lò sưởi, vội nín lại, vì thấy bài Đời lại tái sinh, điểm

cuốn "Cách mạng ở trong đầu: Viết nhật ký dưới thời Stalin".

Cũng một

dòng với Những Kẻ Nói Thầm,

của Orlando Figes.

Gấu đâu còn thì giờ mà đọc!

Thôi thì đọc bài này, thay

cho cuốn sách 800 trang chữ nhỏ.

Tks, and Happy New Year to both of U, O and K.

NQT

*

Sống với VC, cấm nghĩ, theo Sến Cô Nương.

Cái chuyện viết nhật ký, lại càng cấm!

Một số

báo, những ngày đầu.

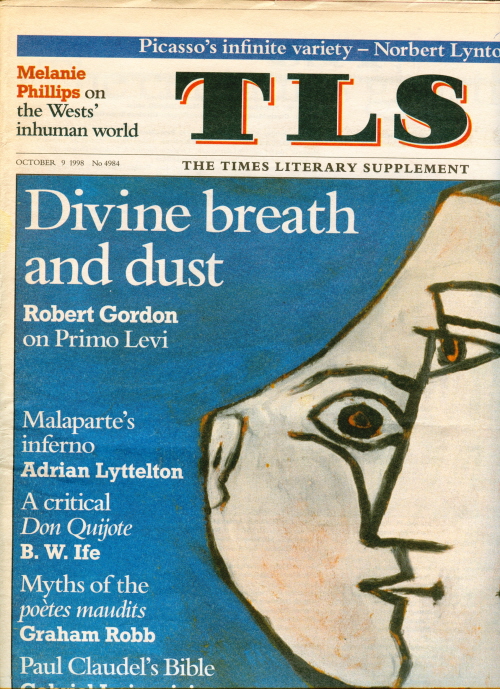

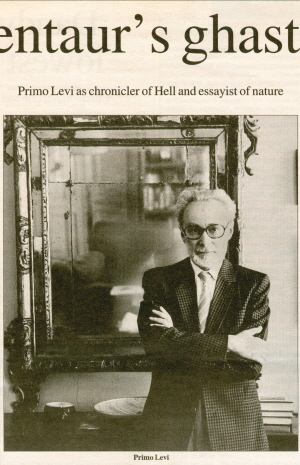

Bài viết về Primo Levi cho mục Tạp Ghi, báo Văn Học của NMG:

Đây là một người,

hay là Bi kịch của một người lạc quan

chôm từ

số báo này.

Cũng đã tính thẩy vô lò sưởi, lại tiếc!

Cái tít mới tuyệt làm sao: Divine Breath and Dust:

Hơi thở thì thánh thiện như

của BHD

Bụi trần thì như thằng cha Gấu!

Ui chao, tẩu hoả nhập ma đến

nơi rồi!

Cái tít bên trong tờ báo, cũng

thật tuyệt:

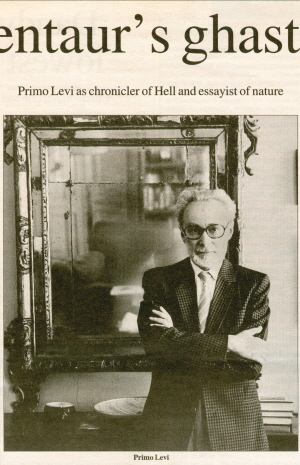

The centaur’s ghastly tale (1)

(1) The

centaur’s

ghastly tale: Câu chuyện khủng

khiếp của con

quái vật.

Centaur: Quái vật, ở đây

được dùng để làm bật ra từ Century, thế kỷ, theo Gấu!

Primo Levi như là một ký sự

gia về Địa Ngục, và tiểu luận gia về thiên

nhiên.

These volumes are

revisionist

in the best sense of the term. We might say schematically that they

offer an

image of Levi as not only a "Dante of our time" (as a recent American

study put it), but also a Montaigne of our time; not only the

chronicler of modern

Hell, but also the probing and mature essayist of the self, human

nature and

nature itself. Even in the preface to his most "infernal" book, If

This Is a Man, Levi's ambition is measured: "[this book] sets out to

provide some material for a calm study of certain aspects of the human

mind." Primo Levi deserves his place in the century's canon not only

for

his accidental and awful encounter with history's whirlwind, as he

called it,

but also for that calm and not so calm study of the human mind, within

and

beyond testimony.

Tuyệt!

*

Một

trong những chương của cuốn sách viết về "Sự hung dữ vô dụng". Những

chi tiết về những trò độc ác của đám cai tù, khi hành hạ tù nhân một

cách vô cớ,

không một mục đích, ngoài thú vui nhìn chính họ đang hành hạ kẻ khác.

Sự hung dữ

tưởng như vô dụng đó, cuối cùng cho thấy, không phải hoàn toàn vô dụng.

Nó đưa

đến kết luận: Người Do thái không phải là người.

(Kinh nghiệm cay đắng này, nhiều

người Việt chúng ta đã từng cảm nhận, và thường là cảm nhận ngược lại:

Những người

CS không giống mình. Ngày đầu tiên đi trình diện cải tạo, nhiều người

sững sờ

khi được hỏi, các người sẽ đối xử như thế nào với "chúng tôi", nếu

các người chiếm được Miền Bắc. Câu hỏi này gần như không được đặt ra

với những

người Miền Nam, và nếu được đặt ra, nó cũng không giống như những người

CSBV tưởng

tượng. Cá nhân người viết có một anh bạn người Nam ở

trong quân đội. Anh chỉ mơ, nếu

có ngày đó, thì tha hồ mà nhìn ngắm thiên nhiên, con người Hà-nội, Miền

Bắc. Lẽ

dĩ nhiên, đây vẫn chỉ là những mơ ước, nhận xét hoàn toàn có tính cách

cá nhân).

*

Primo Levi

deserves his place in the century's canon not only for his accidental

and awful

encounter with history's whirlwind, as he called it, but also for that

calm and

not so calm study of the human mind, within and beyond testimony.

Primo Levi xứng đáng

với chỗ ngồi của ông, theo ‘tiêu chuẩn chọn lựa’, của thế kỷ, không

phải chỉ vì

cuộc gặp gỡ tình cờ, và đáng sợ với ‘cơn gió lớn’ [chữ của ông] của

lịch sử, nhưng

còn là vì cái nhìn trầm ngâm, và cũng không trầm ngâm cho lắm, về cái

đầu của

con người, ở trong vòng, và vượt quá khỏi, chứng liệu.

'Life has been reborn'

Karl Schlagel

REVOLUTION ON MY MIND:

WRITING A DIARY UNDER STALIN

by Jochen Hellbeck.

Harvard, 436 pp., £19.95, May

2006,9780674021747

'THEY ARE BURNING memory.

They've been doing it for a long time ... I go out of my mind when I

think that

every night thousands of people throw their diaries into the fire.' The

Soviet

writer Yuri Tynianov said this to a colleague in Leningrad in the late 1930s. They

were

standing at a window looking at the air outside, which was filled with

a fine

ash. We associate diaries with individualism, intimacy, privacy, with

unrestricted reflection and deliberation. But from a Communist

perspective, to

keep a diary was to withdraw from social responsibility; it was a form

of

apolitical, even asocial behavior.

But

even when the hysterical mass mobilization against 'enemies of the

people',

'spies' and 'other criminal elements' was at its peak, diaries were

being kept

and preserved. A few examples were published in the years of thaw and

de-Stalinization: the diary of Nina Kosterina, for example, was

published in

the 1960s, and that of Julya Piatnitskaya, the wife of Osip Piatnitsky,

a

leading Communist of Lenin's generation who was executed in 1938, found

an

audience via the samizdat of the 1980s. But no one had any idea that so

many

more diaries existed, recording the experiences and thoughts of

thousands of

people, most of them unknown.

And

then in the early 1990S Jochen Helllbeck, a young student at Columbia University,

went to do research in Moscow.

The Soviet Union was changing every day, as new newspapers appeared,

archives

and documents were declassified, and the country experienced a 'happy

summer of

anarchy' as it learned to enjoy its new-found freedom of speech. It was

a

wonderful moment for historians. Strolling through Moscow, Hellbeck was attracted by a

sign

saying People's Archive. He went in and discovered that thousands of

papers and

memoirs had been deposited there, from all levels of society and all

parts of

the country. Written in exercise books or on the backs of official

forms, they

had escaped being turned into ashes.

In Revolution on My Mind Hellbeck

discusses

the diaries of four individuals. The first is Zinaida Denisevskaya, a

member of

the pre-Revolutionary Russian intelligentsia. She kept a diary from

1900, when

she was 13 years old, until her death in 1933. In the year of the

October

Revolution she was a schoolteacher in Voronezh,

a sensitive and well-educated woman who felt isolated from the 'masses

of the

people'. Vorronezh was in Russia's

agricultural heartland and thus affected by the forced collectivization

of the

late 1920S and the Great Famine of the early 1930s. Denisevskaya is

conscious

of the atrocities and absurdities that surround her, but nevertheless

tries to make

the 'truth' of the Party agree with her own observations and

experiences. 'In

its fundamental ideas, the Party is now correct and I am forcing myself

to

overlook petty details,' she notes on the eve of collectivization. 'One

must

not confuse the particular with the general. It is very difficult to

maintain a

broad view all the time, especially for a non-Party member.' She sees

herself

as suffering from the shortcomings of the 'estranged intelligentsia'

and is

filled with desire to join 'the masses'. Finally, she puts herself and

her

class on trial and affirms her own metamorphosis: 'How much has changed

over

these 13 years, both within me and around me! Life has been reborn and

I have

been reborn.' In the end, she came to regard the Soviet regime as the

sole

legitimate repository of the core values of the intelligentsia: social

commitment, mass education, the enlightenment of the people.

The

second diarist here, Stepan Podlubny, faced a different problem. One of

millions of peasants who were swept into the cities and onto

construction sites

during collectivization and the period of accelerated

industrialization, he has

to find his way as the son of a 'kulak' and 'class enemy'. To survive,

to

escape his 'class origins', he must turn from a 'wolf in sheep's

clothing into

a sheep'. Podlubny kept a diary from 1931 until 1939 -with a short

break in

1937, the year of the Great Terror - and from 1941 until he died in

1998. (His

diary was published in German with a commentary by him several years

ago.)

The

entire diary is an exercise in self-observation, as Podlubny works on

and overcomes

his old self. He knows what happened in the villages during the

deportations of

millions of peasants and in the Great Famine. But he is merciless:

All

in all, what's happening is awful. I don't know why, but I don't feel

sympathy

for this. It has to be this way, because then it will be easier to

remake the

peasant's smallholder psychology into the proletarian psychology that

we need.

And those who die of hunger, let them die. If they can't defend

themselves

against death from starvation, it means that they are weak-willed, and

what can

they give to society?

Hellbeck

met Podlubny before he died. He also had an encounter with the third of

his

diarists, Leonid Potemkin. A retired deputy minister of geology of the Soviet Union, Potemkin could look back on a long

and

successful career. Born in 1914, in a village in the Kama River

region, into a petit bourgeois family, he started writing his diary in

1928,

while he was still at school. Of all the diarists his attitudes and

procedures

are the most systematic, even programmatic. He works on his self as

though polishing

a diamond. He is a model vydvishhenets,

the protagonist of upward mobility in the 1930s: a young, cultured,

working-class

man in a white shirt, suit and tie, cultivating the manners of the new

establishment, writing about Tchaikovsky and reciting Heine. 'I feel,'

the

young Potemkin wrote, 'that I will (one day) stand before the court of

society,

where the details of my life will be examined. I feel that I am under

inspection.' For him, as for the historian, his passage from poor

villager to

qualified engineer is the paradigmatic realization of the 'Soviet

dream'.

The

fourth diary is, even in the context of these extraordinary documents,

unique

and at times shocking. Alexander Afinogenov was one of the most

successful

Soviet playwrights of the 1920S and 1930S. The borders between fiction

and fact

are blurred in his diary, which sometimes seems to function as a

notebook for

his future plays, and which covers, in fragments, the period between

1926 and

1941.

Born

in 1904, into the family of a railway employee, Afinogenov was, in his

most

successful years, close to Maxim Gorky and the inner circle of power -

he met

Stalin several times. But in 1937 he was expelled from the Party; some

of his

colleagues (Vladimir Kirrshon, for instance) were killed. Despite this,

he

confesses that the year of the Great Terror was the year of his rebirth

that

the time off ear resulted in his most productive thinking and writing.

'For

him,' Hellbeck says,

the

terror induced a veritable explosion of autobiographical writing. The

Stalinist

purge emerges in his case not as an expression of absolute estrangement

between

state and citizens, but as an intense synergetic link between

individuals and

the state, in which the respective agendas of social purification and

individual self-purification fused ... As the Stalinist regime

increased its

demands for the unmasking of Trotskyist enemies, Afinogennov by means

of his

diary proceeded to scrutinize and cleanse his soul.

In

1938 Afinogenov was reinstated as a Party member. He was convinced that

the

Great Purge was necessary and he wanted to be a participant in it, and

an

active one, prepared to denounce even himself. He saw Stalin as the

architect

of a new world and himself as a bricklayer or, rather, as his master's

inkwell.

Afinogenov died during an air-raid in October 1941, in the building of

the

Central Committee of the Communist Party in Moscow.

All

four diarists express the sense that they live in 'historic times'

worthy of

exact documentation and analysis. They are part of a tradition with

strong

roots in Russian culture, especially in the history of the

intelligentsia, with

its cult of self-perfection and ethos of serving the people. After the

Revolution, the combination of an inferiority complex and a sense of

mission to

represent the nation's conscience came to extend beyond the

intelligentsia. A

new mythos emerged, orchestrated again by intellectuals, that of the

New Man or

Hero, as Gorky

put it.

But

more important was the impact of the huge social upheavals that began

with the

First World War, the Revolution and the Civil War, and continued with

the mass

migrations, famine and violent clashes in a the countryside. Social

identities

disintegrated and were reconfigured by the phenomenon of a whole empire

walking', as the historian Peter Gatrell has described it. The n cities

were overcrowded

with peasants who had lost their stable way of life, their social

position,

their framework of values. These e, diaries show the struggle involved

in

negotiating the extremes of the epoch, in creating a self able to live

simultaneously in the village and in the urban world, in pre-modern and

revolutionary times. The destruction of 'normality' and the permanent

state of

emergency put everyone under almost unbearable pressure, subject to a

violent

and ruthless regime which created entirely new conditions for the

constitution

of a self The classification of social groups - workers, intellectuals,

peasants - proved to be more or less fictitious. As Hellbeck writes,

The

exploding political paranoia of the 1930S, the massive increase in

suspicion

against supposed enemies of the people, also expressed a crisis induced

by the

breakdown of the traditional Marxist tool of class analysis in

evaluating the

individual. Where there were no more alien classes to point to, the

proclivity

to demonize existing obstacles on the road to socialism became

overwhelming.

As

Sheila Fitzpatrick has shown, when the notion of class no longer makes

sense,

and class ascription becomes arbitrary, the desire to construct an

identity, to

make the New Man, becomes powerful. Even such a convinced Communist as

Julya

Piatnitskaya felt the ground shift after the arrest of her husband.

'Who is

he?' she wrote in her diary. Her first inclination was to trust him;

after all,

they had been married for 17 years. But this would mean that the Party

was at

fault. 'Obviously I don't think that. Obviously Piatnitsky was never a

professional revolutionary, but a professional scoundrel - a spy or

provocateur.' Hellbeck comments that

the

diary served as a tool by which she could release her poisonous

thoughts and

thereby regain the assured and unified voice of a devoted

revolutionary. Her

task was to 'prove, not for others, but for yourself ... that you stand

higher

than a wife, and higher than a mother. You will prove with this that

you are a

citizen of the Great Soviet Union. And if you don't have the strength

to do

this, then to the devil with you.'

Jochen

Hellbeck has opened up a new way into the private inner world of the

Stalin

years, a world to which former schools of Soviet history didn't pay

much attention.

These diaries weren't written in 19th century Paris

or Fin-de-siècle Vienna,

in the semi-public space of the Ringstrassen-Cafe or the Parisian

salon. The

permanent flux in what Moshe Lewin has called a 'wind sand society' -

one of

crowded communal apartments with dozens of inhabitants, endless queues

outside

department stores or NKVD offices, an atmosphere of omnipresent fear

and

suspicion - meant that the formation of subjectivity took place in very

different conditions.

Maybe

this will be one of the main implications of Hell beck's discovery.

There can't

now be a cultural history of the 20th century that ignores the

experience of

forging the self under the conditions of Communist - and especially

Stalinist-

rule. It took almost half a century for the diaries kept by the German

Jew

Victor Klemperer between 1933 and 1945 to be discovered and edited, and

more

than half a century to excavate Poddlubny's and Afinogenov's diaries.

Together

they give us a rough idea of what happened to the individual during the

'Age of

Extremes'. *

Đừng đốt, có lửa ở

trong đó… “Chúng là những hồi ký đang cháy. Họ đã từng làm điều này từ

lâu rồi…

Tôi nghĩ mình khùng, khi cho rằng, đêm nào cũng có hàng ngàn người ném

những cuốn

nhật ký của họ vào lửa”. Nhà văn Xô viết, Yuri Tynianov, nói với một

đồng nghiệp ở Leningrad

vào cuối thập

niên 1930. Họ đang đứng ở cửa sổ, nhìn ra bên ngoài, không khí tẩm đẫm

mùi tro

tinh khiết.

Chúng ta coi, nhật ký là những gì liên quan tới chủ nghĩa cá nhân,

cái riêng tư, thầm kín, với những suy tưởng không bị kìm nén. Viết

trong tình

trạng thoải mái, muốn viết gì thì viết. Nhưng, nhìn từ viễn quan

Cộng Sản, giữ, viết nhật ký, là quăng trách nhiệm xã hội vào thùng rác,

một hình

thức vô chính trị, apolitical, có thể nói, một ứng xử cà chớn, vô xã

hội,

asocial. Tuy nhiên, ngay cả vào

những lúc đỉnh cao thời đại của cơn điên cuồng, khùng dại của đám

đông,

con mắt của nhân dân nhìn xó xỉnh nào cũng thấy kẻ thù, gián điệp,

những

trang nhật ký vẫn được gìn giữ, cất giấu, bảo vệ. Một vài cuốn như vậy

đã được

xuất bản trong thời kỳ băng tan và 'de-Stalinization': nhật ký của Nina

Kosterina, đã được xb vào thập niên

1960, và của

Julya Piatnitskaya, vợ của Osip Piatnitsky, một

ông trùm CS thời Lenin, bị hành quyết vào

năm 1938, cuốn nhật ký này đã tìm ra độc giả của nó bằng con đường

chui,

dưói hầm,

[samizdat], vào thập niên 1980.

Nhưng chẳng ai có một ý nghĩ, có bao nhiêu

những cuốn

nhật ký như vậy, ghi lại kinh nghiệm và tư tưởng của

hàng ngàn người, hầu hết là

vô danh, chẳng ai biết tới.

Tại sao

họ tin tưởng vào

Stalin?

Why

They Believed in Stalin

By

Aileen Kelly

Tear

Off the Masks!

Identity

and Imposture in Twentieth-Century Russia

by

Sheila Fitzpatrick

Princeton

University Press,

332 pp., $24.95 (paper)

Revolution

on My Mind:

Writing a Diary Under Stalin

by

Jochen Hellbeck

Harvard University Press, 436 pp., $29.95

In a

work published after he

was expelled from the Soviet Union,

the

dissident writer Alexander Zinoviev depicted a new type of human being:

Homo

sovieticus, a 'fairly disgusting creature' who was the end product of

the

Soviet regime's efforts to transform the population into embodiments of

the

values of communism. In recent years the term has acquired a more

neutral

sense, as material emerging from the archives of the former Soviet

Union -

confessions, petitions and letters to the authorities, personal files,

and

diaries - has given scholars new insights into the ways Russians

responded to

the demand to refashion themselves into model Communists.

NYRB

April 26, 2007

Nikolai

Bukharin by David

Levine

Trong một tác phẩm, viết sau khi bị tống xuất ra khỏi nước mẹ Liên Xô,

nhà văn

ly khai Alexander Zinoviev đã mô tả con người mới xã hội chủ nghĩa, Homo

sovieticus, ''một sinh vật hơi bị ghê tởm', sản phẩm sau cùng của

tất cả

những cố gắng của chế độ Xô Viết nhằm chuyển hóa nhân dân nhập thân vào

những

giá trị ưu việt của Chủ Nghĩa Cộng Sản.

Những năm gần đây, do những nguồn tài liệu mới, con người mới XHCN [thì

cứ nói

đại, con bọ] Homo Sovieticus đó, đã có một cái ý nghĩa trung

tính hơn,

và chúng ta có được những tia sáng mới mẻ, về cung cách, đường hướng

người dân

Nga đáp ứng với đòi hỏi của nhà nước Xô Viết, trong cái việc đẽo gọt

chính họ,

cho đúng khuôn với cái giường Chủ Nghĩa Cộng Sản.

Lạ làm sao, là, con người mới XHCN đó, có những tiền kiếp, nằm trong

những tầng

sâu hoang vắng của văn hoá Nga trước Cách Mạng. Hiện tượng Chúa Sẩy

Thai đó, đã

được tiên tri, "trù ẻo", từ đời thuở nào, giống như tiền căn của một

thứ cỏ, của một miền đất.

Note: Bản scan

"Ác Mộng", từ báo trong nước, đã được làm lớn ra,

theo

yêu cầu của một độc giả Tin Văn. Thân. Kính. NQT

Tại sao họ tin tưởng vào Stalin?

Không

phải tự nhiên, mà Rubashov,

nhân vật của Koestler trong Đêm giữa Ngọ,

Darkness at Noon, bằng lòng thú tội trước bàn thờ, chấp nhận đủ

thứ tội ác

mà Đảng và Nhà nước phịa ra cho ông, bằng lòng thú tội trước tòa án

nhân dân,

chấp nhận tử vì đạo, Đạo Cộng Sản, cái chuyện, một ông nhà văn bi giờ,

[HKP,

xem talawas], đọc nhật ký của đám Nhân Văn Giai Phẩm, cảm thấy bị tình

phụ, ấy

là vì, cho đến bi giờ, nhân loại cũng chưa "vươn tới tầm, chưa đủ

chín", chưa đồng thuận, chưa chịu giao lưu hòa giải, để mà hiểu thấu

đáo,

thảm họa lớn lao, là thảm họa VC trên toàn thế giới, tức Cơn Kinh

Hoàng, Cuộc

Khủng Bố của Stalin, như Aileen Kelly chỉ ra, trong bài viết nêu trên,

cho dù càng

ngày càng có thêm hồ sơ, chứng liệu.

[... that despite the prodigious increase in documentation on the

mentalities

and motives of those who implemented or colluded with Stalin's Terror,

we are

still far from a consensus on the lessons to be drawn from that great

historical catastrophe.].

Cái câu nói, cái nước ta, cái xứ sở ta, nó vốn như vậy, của me-xừ HNH,

có một ý

nghĩa sâu thẳm hơn nhiều, không phải mới có đây, từ cái hồi, hàng

ngoại, chủ

nghĩa Chủ Nghĩa Cộng Sản, theo Bác Hồ, du nhập Việt Nam.

Có mấy

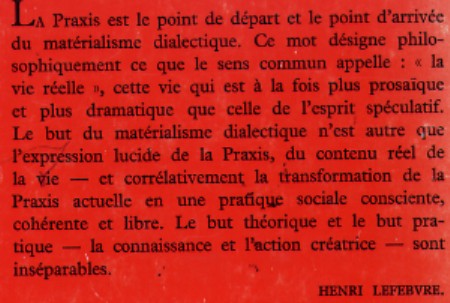

ông Marx?

Nếu chủ nghĩa Marx, qua cái thực hành của nó, đúng như một trong những

ông tổ

sư lý thuyết của nó, Henri Lefebvre,

diễn tả sau đây, thì có một, và chỉ một mà thôi.

Marxism

Cái

Thực Hành là điểm xuất phát

và điểm tới của chủ nghĩa duy vật biện chứng. Từ này chỉ ra, theo nghĩa

triết

học, điều mà thế nhân gọi là "đời sống thực". Cái đời thực này, thì,

cùng lúc, vừa thô kệch, tầm thường, vừa bi thiết, thê lương, còn hơn cả

những

gì mà thế nhân giả định về nó. Mục tiêu của chủ nghĩa duy vật biện

chứng, không

là cái chi đâu đâu, mà chính là biểu hiện rất ư là sáng suốt về Cái

Thực Hành,

về nội dung thực của cuộc đời.....

*

Ui chao, già rồi, sắp xuống lỗ rồi, BHĐ thì cũng đi trước rồi, và đang

chờ,

đúng lúc đó, đọc những câu sau đây, đã từng đọc trên giường bệnh, trong

lúc chờ

Em, kiếm lý do ra khỏi nhà, chạy vội chạy vàng đến nhà thương Đồn Đất,

Sài Gòn

mà chẳng… cảm khái sao!

Le devenir-philosophie du monde est en même temps un devenir-monde de

la

philosophie, sa réalisation est en même temps sa perte, écrit-il à

l'époque où

il rédige sa thèse de doctorat sur La philosophie de la nature chez

Démocrile et Épicure.

Cái trở nên-triết học của thế giới, thì cùng lúc, là

cái trở nên-thế giới

của triết học, thực hiện nó là lúc mất nó...

Gấu chỉ cần đổi, một hai từ trên đây, là ra ý nghĩa thê lương của cuộc

tình của

Gấu:

Vừa có em là lúc mất em!

*

Ui chao, một, áp dụng thông minh và thiên tài chủ nghĩa Mác vào thực tế

Việt

Nam, một, ngu ngơ và dại khờ vào cuộc tình ngất ngư của "cả một thời,

để

yêu và để chết", trước khi con bọ xuất hiện !

*

Bác cháu ta là nhất, là số một, thưa Bác!

Ác Mộng

Cái câu nói, cái nước ta, cái xứ sở ta, nó vốn như vậy, của me-xừ HNH,

có một ý

nghĩa sâu thẳm hơn nhiều.

|