|

Authors on

Museums: at the Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv, the novelist

Adam

Foulds could be one of the exhibits. Going back there for the first

time since

his gap year, he finds it forces him to think again about who he is.

PHOTO

ESSAY

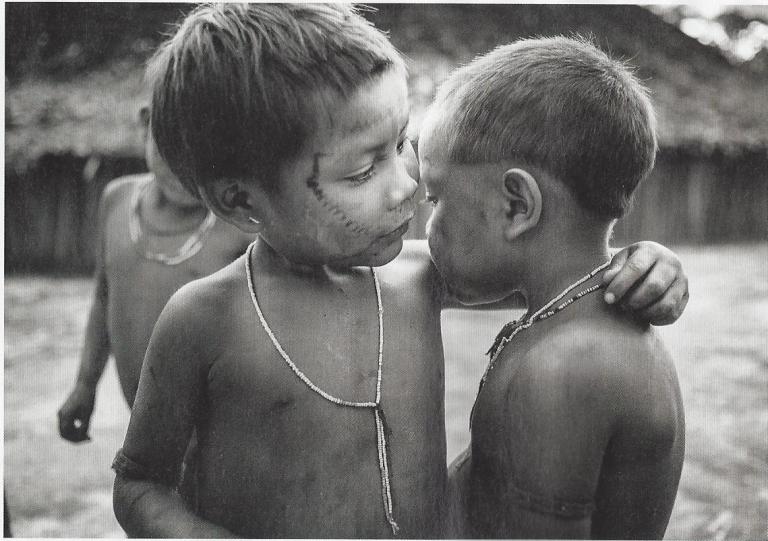

Northern Brazil: deep in the rainforest, modern health care mixes with ancient rituals

CHEKHOV'S

GUIDE TO NOT SLEEPING

~ Posted by

Robert Butler, November 14th 2013 When Anthony

Gardner attended an evening class for us last week on how to sleep

better, he

discovered there were four basic rules. He wasn't the only one keen to

learn

what they were: the class itself was very well attended and his

blogpost was

the most-read article on this site. I was ready

to follow his advice and when I woke at two this morning I remembered

there was

no listening to the radio, no switching on the computer, and no

checking the

phone. Instead I reached for a collection of short stories and picked

the one

which sounded as if it would be the least stimulating. Chekhov's

"A Boring Story" deals with the teeming, raw and uncharitable

thoughts of Nikolai Stepanovich, an eminent professor and privy

counsel, who at

the age of 62 senses his approaching death. "As regards my present

life," he tells us on the second page, "I must first of all mention

the insomnia from which I have begun to suffer lately." This, he says,

is

the "chief and fundamental fact" of his existence. The physical

details in the story belong to the late 19th century, but his

experience would

be familiar to anyone attending the how-to-sleep class. There is the

slow

passage of time—"the clock in the corridor strikes one, then two, then

three"—as Nikolai waits for the cock to crow and the first glimpse of

light beyond the window. There are the sounds of the night—the creak of

the

wardrobe's warped wood and the unexpected hum of the wick in the

lamp—which

carry an excitement of their own. There are the mental games that

Nikolai plays

to get to sleep: counting to a thousand or trying to picture the face

of a

colleague and recall the year he joined the faculty. And, lastly,

there's the

relentlessness of it all: "tomorrow and the day after tomorrow the

nights

will be just as long." The 58 pages

were not nearly boring enough. After finishing it, I lay awake

wondering if

there was a better fictional account of not getting a good night's

sleep. Robert

Butler is online editor of Intelligent Life Image Getty

Rebecca

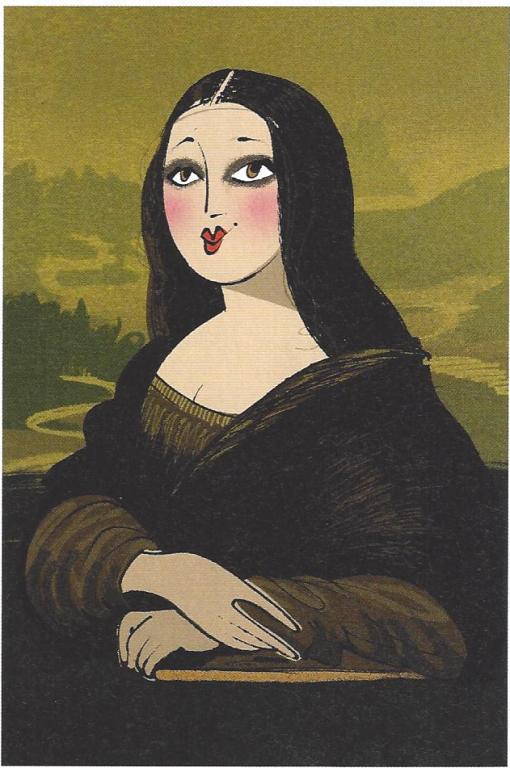

Willis Applied Fashion Ngay cả

thiên thần thì cũng có mặt dơ! Note: Bài

này thú nhất, trong số báo. The world we

live in is literally written on our bodies. Thế giới chúng ta sống được

viết

trên cơ thể bạn. Nhưng đâu chỉ

bộ mặt! Hà, hà! RECENTLY I

WENT to a party as a panda. It wasn't fancy dress - I just put on too

much of a

new, smudgy eyeliner that I'd never used before. Special occasions

prompt us to

want to look our best, and make-up, like clothes, offers the chance to

choose

what that might be. But where on the spectrum from natural to mask-like

artificiality do we want to sit? And even if we know, how do we achieve

it when

there are acres of products on the shelves and we have less than a

square foot

of face on which to put it? After the

panda incident, I decided to get to grips with makeup, in theory and in

practice. While I wear moisturizer daily, eyeliner often and lipstick

sometimes, I have never made the transition to foundation or any sort

of

whole-face make- up. It always seemed odd: as a child you're told to

keep your

face clean, then suddenly as a grown-up you're encouraged to put dirt

on it. I

hate the feeling of having my face covered in gunk which gets on my

clothes and

my phone, and I dislike planting a kiss on a cheek clammy with what the

industry calls "product". The occasional quick swish of compact

powder on a sponge moistened with water is as far as I go. There are

lots of

ways to learn how to apply dirt to your face. The internet is full of

make- up

tutorials, posted both by big companies such as L'Oreal and by

individual women

who just adore make-up and treat it with a high seriousness (see

feature, page

70). Online, I discovered how to find my eye's "outer V"- it starts

at the corner, heads for the outer edge of the brow, then turns inwards

when it

meets the eyelid fold - and also that dabbing on eye shadow is better

than

swiping it, which removes as much color as it applies. Offline, I went

for a

lesson at a department store. Hoping to avoid any more party make-up

malfunctions,

I chose the one called "smokey eye": in fashion-speak, eyes, like

shoes and trousers, go into the singular. I picked up some tips, such

as using

the side of an eyeliner brush to get close to my lashes, and how to do

a flick

in the corner of the eye (rather than go freehand, you continue an

imaginary

line upwards from the lower lid). But after two coats of mascara, which

I don't

normally wear, my eyelids felt they were weightlifting. I went home,

heard the

verdict - "too much" (son); "it makes you look old"

(husband) - then ran upstairs, took it all off, and felt like myself

again. It

is not a coincidence that "made up" means pretend. Why wear

make-up in the first place? The urge to paint ourselves is millennia

old: the

ancient Egyptians had kohl, the ancient Britons woad. Jezebel is on

record in

the Old Testament as making up her eyelids; Elizabeth I and the Kabuki

dancers

of Japan slathered their faces with white lead; native Americans and

other

tribal cultures decorated themselves with bands of color before a

battle. Today

it is part of our culture to paint ourselves before a different sort of

encounter: a social one. The expression "war paint" is an apt one. In her

fascinating book "Bodies" (Profile Books), Susie Orbach describes how

the culture we live in determines the marks we make - or "inscribe" -

on ourselves. The world we live in is literally written on our bodies.

The

objective of make-up nowadays seems to be to mimic the smooth,

even-toned skin

of youth, and, to quote make-up artists and shop assistants, to "open

up

the eye" (singular). They all talk about opening up the eye; this is

not a

surgical procedure, thank goodness, but seems to mean making it look

brighter

and above all bigger. No one could

tell me why that should be so desirable. Then I read that the distance

between eyeball

and eyebrow is a key factor in gender perception, and is much greater

in women

than men. To enlarge that distance is to exaggerate your femininity. And when the

eye itself is widened it is a sign of submission, so opening up the eye

makes

us kittenishly vulnerable. No wonder early feminists went bare-faced.

Narrowing

my eyes, I picked up a book on body language. "The use of lipstick",

it read, "is a technique thousands of years old that is intended to

mimic

the reddened genitals of the sexually aroused female." Was ever a

sentence

more likely to give you pause before whipping a stick of Chanel's Rouge

Allure

out of your handbag? We might just want to reflect a moment on these

things

before we hand over the contents of our wallets to the billion-dollar

cosmetic

industry, and slap our purchases, in the name of improvement, onto our

party-going faces .• |